Penn Central Transportation Company

| |

| Reporting mark | PC |

|---|---|

| Locale | Illinois Indiana Michigan Ohio West Virginia Pennsylvania New York New Jersey Maryland Delaware Connecticut Rhode Island Massachusetts Washington, DC Ontario Quebec |

| Dates of operation | 1968–1976 |

| Predecessor | Pennsylvania Railroad New York Central Railroad New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad |

| Successor | Amtrak Conrail |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

| Electrification | 12.5 kV 25 Hz AC: New Haven-Washington, D.C./South Amboy; Philadelphia-Harrisburg 700V DC: Harlem Line; Hudson Line |

| Length | 20,530 miles (33,040 kilometres) |

| Headquarters | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Website | pcrrhs.org |

The Penn Central Transportation Company, commonly abbreviated to Penn Central, was an American Class I railroad headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, that operated from 1968 until 1976. It was created by the 1968 merger of the Pennsylvania and New York Central railroads. The New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad was added to the merger in 1969; by 1970, the company had filed for what was, at that time, the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Pre-merger

1.2 Merger begins

1.3 Bankruptcy

2 Legacy

3 Corporate history

3.1 Grand Central Terminal

4 Heritage unit

5 See also

6 References

7 Further reading

8 External links

History

Pre-merger

The Penn Central was created as a response to challenges faced by all three railroads in the late 1960s. The Northeast United States is the most densely populated region of the U.S. While railroads elsewhere in North America drew a sizable percentage of revenues from the long-distance shipment of commodities such as coal, lumber, paper and iron ore, northeastern railroads traditionally depended on a more heterogeneous mix of services, including:

commuter rail/passenger rail service

Railway Express Agency freight service- Break-bulk freight service via boxcars

- Consumer goods and perishables (produce and dairy products)

These labor-intensive, short-haul services were vulnerable to competition from automobiles, buses, and trucks, particularly where facilitated by four-lane highways. In 1956, the U.S. Congress passed the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. This law authorized construction of the Interstate Highway System, which provided an economic boost to the trucking industry.[1]

Another problem was the inability to respond to market conditions. At the time, U.S. railroads were regulated by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), which did not allow railroads to change rates it charged both shippers and passengers. Reducing costs was the only way to survive and become profitable, but the ICC restricted what cost-cutting could take place. A merger seemed to be a promising way out of a difficult situation.[2]

The Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) and New York Central Railroad (NYC) had been significant rivals for most of the 20th century. Both railroads had physical plant not being utilized to capacity (though the NYC was in better shape); both had a heavy passenger business; neither was earning much money. Talks of a merger had been announced as early as 1957.[2] The initial reaction in the industry was utter surprise. Every merger proposal for decades had tried to balance the two giant railroads against each other and create two, three, or four more-or-less equal systems in the east. Traditionally, the PRR had been allied with the Norfolk & Western (N&W) and Wabash railroads; the NYC with the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O), Reading (RDG) and Delaware, Lackawanna & Western (DL&W) railroads. Any remaining players were swept up with the Erie Railroad and the Nickel Plate.[2] In addition, tradition favored end-to-end mergers rather than those of parallel railroads.[2]

Planning and justifying the merger took nearly a decade, during which time the eastern railroad scene changed dramatically, in large measure because of the impending merger of the NYC and PRR. The Erie merged with the DL&W to create the Erie Lackawanna Railway (EL) in 1960, the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway (C&O) acquired control of the B&O, and the N&W took in several railroads, including the Nickel Plate and Wabash.[2]

Merger begins

"Public Interest Demands Merger" publicity booklet produced by PC Merger Information Committee in 1962 to inform the public on issues concerning the proposed merger.

Conferring outside Hearing Room of Interstate Commerce Commission in Washington, D.C., NYC president Alfred E. Perlman (right) confers with PRR chairman Stuart W. Saunders about employee protection agreement.

Cover of PC employee newsletter. Post-sheet metal worker A. A. Muhlbauer of Samuel Rea Shops in Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania, uses hydraulic riveter to affix cap to cover seam of boxcar's roof sheets in PC's 1970 campaign to construct new cars to improve business.

The merger formally closed on February 1, 1968. On that date, the PRR — the nominal survivor of the merger — changed its name to Pennsylvania New York Central Transportation Company. It shortened its name to Penn Central Company on May 8, 1968. On October 1, 1969, Penn Central reorganized as a holding company, with its railroad interests under a wholly owned subsidiary, Penn Central Transportation Company.[2]

The ICC approved the merger on the following conditions:

- The new company had to take over the freight and passenger operations of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad (NH). That occurred on December 31, 1968.

- PC had to absorb the New York, Susquehanna & Western Railway (NYS&W). PC and NYS&W could not agree on a price, and eventually NYS&W became part of the Delaware Otsego System.

- PC had to make the Lehigh Valley Railroad (LV) available for merger by either N&W or C&O or, if neither of those railroads wanted it, merge it into PC. LV struggled along on its own and entered bankruptcy only three days after PC did.[2]

The merger was not a success. An implementation plan was drawn up, but not carried out. Attempts to integrate operations, personnel and equipment were unsuccessful, due to clashing corporate cultures, incompatible computer systems and union contracts.[3]:233–234 Little thought had been given to unifying the two railroads, which had dramatically different styles of operation. In the decade prior to the merger, the NYC had trimmed its physical plant and assembled a young, eager management group under the leadership of Alfred E. Perlman. The PRR, headed by Stuart T. Saunders, had been a more conservative and traditional operation. Many of NYC's management people (known as the "green team") saw that the PRR (the "red team") was dominant in PC management and soon left for other positions. Those who departed had often said the different corporate philosophies (PRR branded itself as a transportation company, while the NYC considered itself a railroad company) could never have merged successfully.[2] The network was so poorly integrated that trains were lost on a regular basis; PC classification clerks struggled to properly dispatch cars across PC's entangled routing system.[4]

In addition to the problems of unification, the industrial states of the northeast and midwest were fast becoming the rust belt. As industries shut down and relocated, railroads found themselves with excess capacity. The PRR was particularly burdened with excess trackage; in many cases, it had four to six tracks where one or two would do. Even though this track was no longer needed, it was still on the tax rolls. West of the Allegheny Mountains, NYC and PRR duplicated each other at almost every major point; east of the Alleghenies, the two hardly touched. Railroad historian George Drury commented that the merger resembled "a late-in-life marriage to which each partner brings a house, a summer cottage, two cars, and several complete sets of china and glassware — plus car payments and mortgages on the houses."[2]

Subpar track conditions deteriorated further, a result of inheriting decrepit facilities. Trains regularly operated at greatly reduced speeds, resulting in delayed shipments, excessive overtime accrued, and soaring operating costs. Derailments and wrecks were regular occurrences, particularly in the Midwest.[4] In 1969, most of Maine's potato production rotted in the PC's Selkirk Yard, hurting the Bangor & Aroostook Railroad, whose shippers vowed never to ship by rail again.[5] At one point, Penn Central was losing $1 million per day.[4]

PC's holding company tried to diversify the troubled firm into real estate and other non-railroad ventures, but in a slow economy these businesses performed little better than the railroad assets. In addition, these new subsidiaries diverted management attention away from the problems in the core business. Management also insisted on paying dividends to shareholders to create the illusion of success. The company had to borrow additional funds to maintain operations. Interest on loans had become an unbearable financial burden.

Bankruptcy

PC locomotives #4801 and #4800, both former PRR GG1s, haul freight through North Elizabeth, New Jersey in December 1975.

PC locomotive #4312, an EMD E8, at Bay Head yard, Bay Head, New Jersey, April 18, 1971.

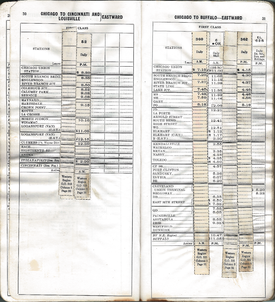

Penn Central Employee Timetable, Western Region No.5 showing frequent train annulments and retimings by General Order in the bankruptcy era.

PRR and NYC came into the merger in the black, but PC's first year of operation yielded a deficit of $2.8 million ($20.2 million today). In 1969 the deficit was nearly $83 million ($567 million today). PC's net income for 1970 was a deficit of $325.8 million ($2.1 billion today). By then the railroad had entered bankruptcy proceedings — specifically on June 21, 1970. The nation's sixth largest corporation had become its largest bankruptcy[2][4] (the Enron Corporation's 2001 bankruptcy eclipsed this in large measure). Although the PC was put into bankruptcy, its parent Penn Central Company was able to survive. The devastating effects of Hurricane Agnes in 1972 further hampered PC operations, destroying many important branches and main lines.[6]

PC unsuccessfully attempted to sell off the air rights to Grand Central Terminal, and allow developers to build skyscrapers above the terminal, in order to fund continued operations. The resulting lawsuit, Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City, was decided in 1978 where the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that PC could not sell Grand Central's air rights because the terminal was a New York City designated landmark.[7][8]

The reorganization court ruled in May 1974 that PC was not reorganizable on the basis of income. A U.S. government corporation, the United States Railway Association, was formed under the provisions of the Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973 to develop a plan to save PC. The outcome was that Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail), owned by the U.S. government, took over railroad properties and operations of PC (and six other railroads: EL, LV, RDG, Lehigh & Hudson River Railway, Central Railroad of New Jersey, and Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines) on April 1, 1976.[9] It was a major step toward nationalization of the railroads in the U.S. They had been nationalized briefly during World War I, but the U.S. had held out against a world-wide trend toward nationalization of railroads until the creation of Amtrak which nationalized the country's passenger trains, on May 1, 1971.[2] Amtrak initially operated a skeleton passenger service on PC trackage as well as other U.S. railroads.

PC participated in two passenger service experiments in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation (U.S. DOT). Both were aimed at upgrading passenger service in the Northeast Corridor. Between New York City and Washington, D.C., PC inherited the Metroliner experiment that the PRR and U.S. DOT had begun — fast electric trains that were intended for a maximum speed of 160 mph (257 km/h). The inauguration of service was delayed several times, and when it did begin, it was not shown in The Official Guide. The Metroliner was not an absolute success, but it reversed a long decline in ridership on the New York-Washington run. On the Boston-New York run PC operated a United Aircraft TurboTrain in an effort to beat the 3-hour-55-minute running time of the NH's expresses of the early 1950s. Information about TurboTrain schedules was even more difficult for the public to obtain than Metroliner timetables. The combination of untested equipment, track that had been allowed to deteriorate, and the general incongruity of space-age technology and traditional railroad thinking made the services the butt of considerable satire. Most of the Metroliner cars were stored out of service for a time (Amtrak converted them into cab control cars for Harrisburg-New York City Keystone Service in 2007) and the TurboTrains were scrapped altogether. PC's intercity passenger service was taken over by Amtrak on May 1, 1971. The commuter service, which was already subsidized by local authorities, passed first to Conrail and then to other operating authorities (SEPTA, New Jersey Transit, Metro-North Railroad, etc.)[2]

Facing continued loss of market share to the trucking industry, the railroad industry and its unions asked the federal government for deregulation. The 1980 Staggers Act, which deregulated the railroad industry, proved to be a key factor in bringing Conrail and the old PC assets back to life.[10] During the 1980s, the deregulated Conrail had the muscle to implement the route reorganization and productivity improvements that the PC had unsuccessfully tried to implement during 1968 to 1970. Hundred of miles of former PRR and NYC trackage were abandoned to adjacent landowners or rail trail use. The stock of the subsequently-profitable Conrail was refloated on Wall Street in 1987, and the company operated as an independent, private-sector railroad from 1987 to 1999.

Legacy

The Penn Central bankruptcy was a cataclysmic event, both to the railroad industry and the nation's business community. The PC and its problems have been the subject of more words than almost anything else in the railroad industry, everything from diatribes on the passenger business to analyses of the reason for its collapse. Of the failed merger, Saunders commented "Because of the many years it took to consummate the merger, the morale of both railroads was badly disrupted and they were faced with unmanageable problems which were insurmountable. In addition to overcoming obstacles, the principal problem was too much governmental regulation and a passenger deficit which amounted to more than $100 million a year."[11]

As the mega-railroad's brief existence has rarely been looked upon favorably by railroad historians and former employees, almost nothing specifically aimed at the railroad enthusiast has been published about the Penn Central.[2] The preservation group Penn Central Railroad Historical Society was formed in July 2000 to preserve the history of the often scorned company.[12] The 2003 publication The Untold Story of the Survival of the Penn Central Company by Donald Prell detailed the PC's survival during its lengthy bankruptcy proceedings.[13]

Corporate history

PC pre-bankruptcy stock certificate, 1969.

PC post-bankruptcy stock certificate, 1974.

The Pennsylvania New York Central Transportation Company was formed February 1, 1968, as an absorption of the NYC by the PRR. The trade name of "Penn Central" was adopted, and on May 8, the company was officially renamed to the Penn Central Company.

The Penn Central Transportation Company (PCTC) was incorporated on April 1, 1969, and its stock was assigned to the new Penn Central Holding Company. On October 1, the PCTC merged into the Penn Central Company. The next day, the Penn Central Company was renamed to the Penn Central Transportation Company, and the Penn Central Holding Company became the Penn Central Company.

The old Pennsylvania Company, a holding company chartered in 1870, reincorporated in 1958, and long a subsidiary of the PRR, remained a separate corporate entity throughout the period following the merger. While the PCTC had been merged into Conrail in 1976, the holding company, the Penn Central Company, continued as a separate firm. In the 1970s and 1980s, the new PC was a small conglomerate that largely consisted of the diversified sub-firms acquired by the old PC before the crash.

Among the properties Penn Central owned when Conrail was created were the Buckeye Pipeline and a 24 percent stake in Madison Square Garden (which stands above Penn Station) and its prime tenants, the New York Knicks basketball team and New York Rangers hockey team.

Though the new PC retained ownership of some rights of way and station properties connected with the railroads, it continued to liquidate these and eventually concentrated on one of its subsidiaries in the insurance business. Penn Central Corporation changed its name to American Premier Underwriters in March 1994. It became part of the Cincinnati financial empire of Carl Lindner and his American Financial Group.

Grand Central Terminal

Up until late 2006, American Financial Group, still owned Grand Central Terminal, though all railroad operations were managed by the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) through a lease entered into in 1994. The current lease with the MTA was negotiated to last through February 28, 2274.

On December 6, 2006, the U.S. Surface Transportation Board approved the sale of several of American Financial Group's remaining railroad assets to Midtown TDR Ventures LLC[14] for approximately US$ 80 million. The New York Post on July 6, 2007 reported that Midtown TDR was controlled by Penson and Venture. The Post noted that the MTA would pay $2.24 million in rent in 2007 and has an option to buy the station and tracks in 2017. However, Argent could also opt to extend the date another 15 years to 2032.[15]

The assets included the 156 miles (251 km) of rail used by the Metro-North Railroad Harlem and Hudson Lines, and Grand Central Terminal in New York City. The most valuable asset cited by Midtown TDR were the unused "air rights" for additional development above Grand Central's underground boarding platforms and switch yard. The platforms and yards extend for several blocks north of the terminal building under numerous streets and existing buildings leasing air rights, including the famous MetLife Building and Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. The cash value of the Terminal building itself is limited. In spite of the fact the Terminal was originally designed to accommodate a skyscraper above it, as the building is listed for purposes of historic preservation it cannot, under current law, be torn down for redevelopment.[15]

In November 2018, the MTA proposed purchasing the Hudson and Harlem Lines as well as the Grand Central Terminal for up to $35.065 million, plus a discount rate of 6.25%. The purchase would include all inventory, operations, improvements, and maintenance associated with each asset, except for the air rights over Grand Central.[16] The MTA's finance committee approved the proposed purchase on November 13, 2018, and the purchase was approved by the full board two days later.[17][18] Under the terms of the deal, the MTA purchased Grand Central Terminal, as well as the Hudson Line from Grand Central to a point 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Poughkeepsie, and the Harlem Line from Grand Central to Dover Plains.[19]

Heritage unit

As part of Norfolk Southern Railway's 30th anniversary, the railroad painted 20 new locomotives utilizing former liveries of predecessor railroads. Unit number 1073, a SD70ACe, is painted in a Penn Central Heritage scheme.[citation needed]

See also

Alfred E. Perlman - PC President

Stuart T. Saunders - PC Chairman & CEO- History of rail transport in the United States

Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City (1978 Supreme Court case)- Survival of the Penn Central (https://archive.org/details/SurvivalOfThePennCentral_201501)

References

^ Geisst, Charles R. (2006). Encyclopedia of American Business History, Volume 2. New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-8160-4350-7..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ abcdefghijklm Drury, George H. (1994). The Historical Guide to North American Railroads: Histories, Figures, and Features of more than 160 Railroads Abandoned or Merged since 1930. Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing. pp. 215, 248–251. ISBN 0-89024-072-8.

^ Stover, John F. (1997). American Railroads (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-77658-3.

^ abcd "American-Rails.com: The Penn Central Railroad". Retrieved 2010-12-16.

^ Schafer, Mike (2000). More Classic American Railroads. Osceola, WI: MBI Publishing Co. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-7603-0758-8. OCLC 44089438.

^ Baer, Christopher T. "PRR Chronology: A General Chronology of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company Predecessors and Successors and its Historical Context". PRR CHRONOLOGY 1972 June 2005 Edition. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

^ Penn Central Transp. Co. v. New York City, 438 U.S. 104, 135 (U.S. 1978).

^ Weaver, Warren Jr. (June 27, 1978). "Ban on Grand Central Office Tower Is Upheld by Supreme Court 6 to 3". The New York Times. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

^ Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act, Pub. L. 94-210, 90 Stat. 31, 45 U.S.C. § 801. February 5, 1976

^ Staggers Rail Act of 1980, Pub. L. 96-448, 94 Stat. 1895. Approved 1980-10-14.

^ Goldman, Ari L. (February 9, 1987). "Stuart T. Saunders, Driver Force Behind Penn Central, Dies at 77". The New York Times. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

^ pcrrhs.org

^ Prell, Donald (2003). The Untold Story of the Survival of the Penn Central Company. eBook Edition. Strand Publishing,

ISBN 0-9741975-0-5.https://archive.org/details/SurvivalOfThePennCentral_201501

^ U.S. Surface Transportation Board. Washington, D.C. (2006-12-06). "Midtown TDR Ventures LLC – Acquisition Exemption – American Premier Underwriters, Inc., The Owasco River Railway, Inc., and American Financial Group, Inc." Decision Document no. FD_34953_0.

^ ab Air Rights Make Deals Fly - New York Post - July 6, 2007

^ "Metro-North Railroad Committee Meeting November 2018" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. November 13, 2018. pp. 73–74. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

^ Berger, Paul (November 13, 2018). "After Years of Renting, MTA to Buy Grand Central Terminal". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

^ "New York's Grand Central Terminal sold for US$35m". Business Times. November 20, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

^ "MTA to buy Grand Central, Harlem and Hudson lines for $35M, opening development options". lohud.com. November 13, 2018. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

Further reading

Daughen, Joseph R. & Peter Binzen (1999). The Wreck of the Penn Central (2nd edition). Boston: Beard Books Little, Brown. ISBN 1-893122-08-5.

Prell, Donald (2003). The Untold Story of the Survival of the Penn Central Company (eBook 2010 ed.). Palm Springs: Strand Publishing. ISBN 0-9741975-0-5.

Salsbury, Stephen (1982). No Way to Run a Railroad. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-054483-2.

Sobel, Robert (1977). The Fallen Colossus. New York: Weybright and Talley. ISBN 978-0-679-40138-4.

External links

"Penn Central Document, Timetable and Publication Archive". Unlikely PCRR.

"Penn Central Information". Penn Central Railroad USA at Tripod.com.

"Penn Central Maps and Track Diagrams". Penn Central Railroad Online.

"Penn Central Railroad Historical Society". pcrrhs.org.