Hwicce

Kingdom of the Hwicce | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 577–780s | |||||||||

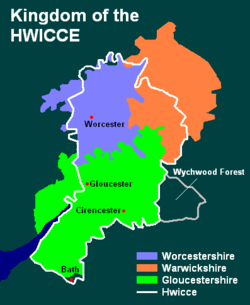

Kingdom of the Hwicce (with later counties). Wychwood Forest, a former Hwicce territory, had apparently been lost before 679. | |||||||||

| Capital | Worcester | ||||||||

| Religion | Paganism, Christianity | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Historical era | Heptarchy | ||||||||

• Established | 577 | ||||||||

• Assimilated into Mercia | 780s | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Hwicce (Old English: [ʍi:kt͡ʃe], /hw-ik-chay/) was a tribal kingdom in Anglo-Saxon England. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the kingdom was established in 577, after the Battle of Deorham. After 628, the kingdom became a client or sub-kingdom of Mercia as a result of the Battle of Cirencester.

The Tribal Hidage assessed Hwicce at 7000 hides, which would give it a similar sized economy to the kingdoms of Essex and Sussex.

The exact boundaries of the kingdom remain uncertain, though it is likely that they coincided with those of the old Diocese of Worcester, founded in 679–80, the early bishops of which bore the title Episcopus Hwicciorum. The kingdom would therefore have included Worcestershire except the northwestern tip, Gloucestershire except the Forest of Dean, the southwestern half of Warwickshire, the neighbourhood of Bath north of the Avon, plus small parts of Herefordshire, Shropshire, Staffordshire and north-west Wiltshire.[1][2]

Contents

1 Name

2 History

3 Kings of the Hwicce

4 Ealdormen of the Hwicce

5 Other notables of the Hwicce

6 Notes

7 Further reading

Name

The etymology of the name Hwicce "the Hwiccians" is uncertain. It is the plural of a masculine i-stem. It may be from a tribal name of "the Hwiccians", or it may be from a clan name.

One etymology comes from the common noun hwicce "ark, chest, locker", in reference to the appearance of the territory as a flat-bottomed valley bordered by the Cotswolds and the Malvern Hills.[3] A second possibility would be a derivation from a given name, "the people of the man called Hwicce", but no such name has been recorded.[4][5]Eilert Ekwall connected the name, on linguistic grounds, with that of the Gewisse, the predecessors of the West Saxons.[6] Also suggested by Smith is a tribal name that was in origin pejorative, meaning "the cowards", cognate to quake, Old Norse hvikari "coward". It is also likely that "Hwicce" referred to the native tribes living along the banks of the River Severn, in the area of today's 'Worcester', who were weavers using rushes and reeds growing profusely to create baskets. The modern word 'wicker', which is thought to be of Scandinavian origin, describes the type of baskets produced by these early people. However, there are potential objections to many of these possible explanations. For instance, Coates argues that the essence of an ark is that it is closed, rather than open like a valley or plain; that no cognate of hvikari or contemporary version of wicker is known, and that no full etymological argument to relate Gewisse to Hwicce has been advanced.[7]

Stephen Yeates (2008, 2009) has interpreted the name as meaning "cauldron; sacred vessel" and linked to the shape of the Vale of Gloucester and the Romano-British regional cult of a goddess with a bucket or cauldron, identified with a Mater Dobunna, supposedly associated with West Country legends concerning the Holy Grail.[8] However, his interpretation has been widely dismissed by academics.[9]

Coates (2013) on the other hand believes that the name has a Brythonic origin, related to the modern Welsh gwych[10] meaning 'excellent'.[11] The prefix hy is an emphatic (roughly meaning 'very') giving something similar to hywych. Similar known constructions in Welsh include "hydda ‘(very) good’, hynaws ‘good-natured’, hylwydd ‘successful’, hywiw ‘(very) worthy’ and hywlydd ‘(very) generous’".[12] Coates notes that the meaning would be "comparable with bombastic British tribal names of the Roman period, such as Ancalites ‘the very hard ones’, Catuvellauni ‘the battle-excellent ones’ or Brigantes ‘the high ones’".[13] Coates does however admit that his explanation can also raise objections, not least that hywych is not a recorded and known early or later Welsh word.

The toponym Hwicce survives in Wychwood in Oxfordshire, Whichford in Warwickshire, Wichenford, Wychbury Hill and Droitwich in Worcestershire. (The 'wich' part of Droitwich is also commonly thought to refer to salt production in that area). The local government district of Wychavon derived the first element of its name from the old kingdom also.

History

The territory of the Hwicce may roughly have corresponded to the Roman civitas of the Dobunni.[14] The area appears to have remained largely British in the first century or so after Britain left the Roman Empire, but pagan burials and place names in its north-eastern sector suggest an inflow of Angles along the Warwickshire Avon and perhaps by other routes;[15] they may have exacted tribute from British rulers.[16]

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, there was a Battle at Dyrham in 577 in which the Gewisse (West Saxons) under Ceawlin killed three British kings and captured Gloucester, Cirencester and Bath. West Saxon occupation of the area did not last long, however, and may have ended as early as 584, the date of the battle of Fethanleag, according to the A.S.C., in which Cutha was killed and Ceawlin returned home in anger, and certainly by 603 when, according to Bede, Saint Augustine attended a conference of Welsh bishops "at St. Augustine's Oak on the borders of the Hwicce and the West Saxons".

The Angles strengthened their influence over the area in 628, when (says the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle), the West Saxons fought the (Anglian) Penda of Mercia at Cirencester and afterwards came to terms. Penda had evidently won but had probably forged an alliance with local leaders since the former Dobunnic polity did not immediately become part of Mercia but instead became an allied or client kingdom of the Hwicce.

The Hwicce sub-kingdom included a number of distinct tribal groups, including the Husmerae, the Stoppingas and the Weorgoran.[17]

The first probable kings of whom we read were two brothers, Eanhere and Eanfrith. Bede notes that Queen Eafe "had been baptised in her own country, the kingdom of the Hwicce. She was the daughter of Eanfrith, Eanhere's brother, both of whom were Christians, as were their people."[18] From this, we deduce that Eanfrith and Eanhere were of the royal family and that theirs was a Christian kingdom.

It is likely that the Hwicce were converted to Christianity by Celtic Christians rather than by the mission from Pope Gregory I, since Bede was well-informed on the latter yet does not mention the conversion of the Hwicce.[19] Though place-names show that Anglo-Saxon settlement was widespread in the territory, the limited spread of pagan burials, along with two eccles place-names that invariably identify Roman-British churches, suggests that Christianity survived the influx. There are also probable Christian burials beneath Worcester Cathedral and St Mary de Lode Church, Gloucester.[20] So it seems that incoming Anglo-Saxons were absorbed into the existing church. The ruling dynasty of the Hwicce were probably key figures in the process. Perhaps they sprang from intermarriage between Anglian and British leading families.

By a complex chain of reasoning, one can deduce that Eanhere married Osthryth, daughter of Oswiu of Northumbria, and had sons by her named Osric, Oswald and Oshere. Osthryth is recorded as the wife of Æthelred of Mercia. An earlier marriage to Eanhere would explain why Osric and Oswald are described as Æthelred's nepotes — usually meaning "nephews" but here probably "stepsons".[21]

Osric was anxious for the Hwicce to gain their own bishop,[22] but it was Oshere whose influence was seen behind the creation of the see of Worcester in 679–80. Presumably Osric was dead by that time. Tatfrid of Whitby was chosen as the first bishop of the Hwicce but he died before ordination and was replaced by Bosel.[23] A 12th-century chronicler of Worcester comments that that town was selected as the seat of the bishop because it was the capital of the Hwicce.[24]

Oshere was succeeded by his sons Æthelheard, Æthelweard and Æthelric. At the beginning of Offa's reign we find the kingdom ruled by three brothers, named Eanberht, Uhtred and Aldred, the two last of whom lived until about 780. After them the title of king seems to have been given up. Their successor Æthelmund, who was killed in a campaign against Wessex in 802, is described only as an earl.

The district remained in possession of the rulers of Mercia until the fall of that kingdom. Together with the rest of English Mercia, it submitted to King Alfred about 877–883 under Earl Æthelred, who possibly himself belonged to the Hwicce.

Kings of the Hwicce

No contemporary genealogy or list of kings has been preserved, so the following list has been compiled by historians from a variety of primary sources.[25] Some kings of the Hwicce seem to have reigned in tandem for all or part of their reign. This gives rise to an overlap in the dates of reigns given below. Please consult individual biographies for a discussion of the dating of these rulers.

| Name | Dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 628 | Kingdom conquered by Penda of Mercia. | |

| Eanhere | mid-7th century | |

| Eanfrith | mid-7th century | Brother of Eanhere. |

| Osric | active 670s | Entombed in Gloucester Cathedral. |

| Oshere | active 690s | Brother of Osric. Died before 716. |

| Æthelheard | active 709 | Son of Oshere. Issued charter with Æthelweard. |

| Æthelweard | active 709 | Son of Oshere. |

| Æthelric | active 736 | Son of Oshere. |

| Eanberht | active 750s | Not recorded after 759. |

| Uhtred | active 750s – 779 | |

| Ealdred | active 750s – 778 | |

| 780s | Assimilation of the Hwicce into Mercia is completed. |

Ealdormen of the Hwicce

An ealdorman was a high-ranking royal official and prior magistrate of an Anglo-Saxon shire. The term was rendered in Latin as dux, præfectus or comes, it is the equivalent of an earl.

| Name | Dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Æthelmund | c. 796-802 | Died in battle 802.[26] |

| ?Æthelric | fl. 804 | Son of Æthelmund. His will of 804 requests burial at Deerhurst.[1] |

| Leofwine | d.c.1023 | Father of Leofric, Earl of Mercia |

| Odda | d.1056 | Built Odda's Chapel at Deerhurst for the soul of his brother Ælfric.[27] Buried at Pershore.[28] The area of his jurisdiction probably did not include the Hwicce.[29] |

Other notables of the Hwicce

Æthelmod granted land to Abbess Beorngyth in October 680 and was probably a member of the royal family.[2]

Osred (c. 693) was a thegn of the Hwicce, who has been described by some historians as a king.[30]

Notes

^ Della Hooke, The Kingdom of the Hwicce (1985), pp.12-13

^ Stephen Yeates, The Tribe of Witches (2008), pp.1-8

^ J. Insley, "Hwicce" in: Hoops (ed.) Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 15, Walter de Gruyter, 2000, .mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

ISBN 978-3-11-016649-1, p. 295.

^ William Henry Duignan, Notes on Staffordshire place names, 1902.

^ A. H. Smith, 'The Hwicce', in Medieval and Linguistic Studies in Honour of F. P. Magoun (1965), 56-65.

^ Eilert Ekwall, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names (Oxford Clarendon Press, reprinted 1991)[page needed]

^ Coates 2013, pp. 4–5

^ Stephen J. Yeates, The Tribe of Witches: The religion of the Dobunni and Hwicce, Oxbow Books (2008). Stephen Yeates, A Dreaming for the Witches (2009).[unreliable source?]

^ Coates 2013, p. 5 for instance

^ Coates 2013, p. 9

^ "Gwych". Geiriadur: Welsh-English / English-Welsh On-line Dictionary. University of Wales Trinnity St David.

^ Coates 2013, p. 9

^ Coates 2013, p. 9

^ J. Manco, Dobunni to Hwicce, Bath History, vol. 7 (1998).

^ D.Hooke, The Anglo-Saxon Landscape: The Kingdom of the Hwicce (Manchester, 1985), pp.8–10; Sims-Williams, 'St Wilfred and two charters dated AD 676 and 680', Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 39, part 2 (1988), p.169.

^ N.Higham, The English Conquest: Gildas and Britain in the fifth century (Manchester, 1994), chaps. 2, 5.

^ David P. Kirby, The earliest English Kings (Routledge, 1990, 2000)

^ Bede, The Ecclesiastical History of the English People ed. J.McClure and R.Collins (Oxford, 1994), p.193.

^ J. Manco, Saxon Bath: The Legacy of Rome and the Saxon Rebirth, Bath History, vol. 7 (1998).

^ C. Thomas, Christianity in Roman Britain to AD 500 (1981), pp.253–71; Hooke, p.10; C. Heighway, 'Saxon Gloucester' in J. Haslam ed., Anglo-Saxon Towns in Southern England (Chichester, 1984), p.375.

^ John Leland, Collectanea, vol. 1, p. 240.

^ Charter S 51, MS Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, 111, pp. 59-60 (s. xii2)S51

^ Bede, The Eccesiastical History of the English People, ed. J. McClure and R. Collins (1994), p. 212; Chronicle of John of Worcester ed. and trans. R.R. Darlington, J. Bray and P. McGurk (Oxford 1995), 136–8.

^ "The Chronicle of Florence of Worcester" in The Church Historians of England ed. and trans. J. Stevenson, vol. 2, p.379.

^ The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England, ed. M. Lapidge (Blackwell 1999), 507.

^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

^ Inscription on the chapel: "Earl Odda had this Royal Hall built and dedicated in honour of the Holy Trinity for the soul of his brother, Aelfric, which left the body in this place. Bishop Ealdred dedicated it the second of the Ides of April in the fourteenth year of the reign of Edward, King of the English."

^ Victoria County History of Worcestershire, Vol.2, p.128.

^ See Earl Odda

^ For example he appears on this list of Kings of Hwicce. Retrieved on 10 March 2005.

Further reading

Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Hwicce. |

Hooke, Della (1985). The Anglo-Saxon Landscape: The Kingdom of the Hwicce.

Sims-Williams, Patrick (2004). "Hwicce, kings of the (act. c.670–c.780)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

Sims-Williams, Patrick (1990). Religion and Literature in Western England, 600-800. Cambridge Studies in Anglo-Saxon England 3. Cambridge.

Coates, Richard (2013). "The name of the Hwicce: A discussion". Anglo-Saxon England. 42: 51–61. doi:10.1017/S0263675113000070. ISSN 0263-6751.