Defender (association football)

In the sport of association football, a defender is an outfield player whose primary role is to prevent the opposing team from scoring goals.

There are four types of defenders: centre-back, sweeper, full-back, and wing-back. The centre-back and full-back positions are essential in most modern formations. The sweeper and wing-back roles are more specialised for certain formations.

Contents

1 Centre-back

2 Sweeper (libero)

3 Full-back

4 Wing-back

5 See also

6 References

Centre-back

Centre-back John Terry (26, blue) closely marks centre-forward Didier Drogba.

A centre-back (also known as a central defender or centre-half) defends in the area directly in front of the goal, and tries to prevent opposing players, particularly centre-forwards, from scoring. Centre-backs accomplish this by blocking shots, tackling, intercepting passes, contesting headers and marking forwards to discourage the opposing team from passing to them.

The common 4–4–2 formation uses two centre-backs.

With the ball, centre-backs are generally expected to make long and pinpoint passes to their teammates, or to kick unaimed long balls down the field. For example, a clearance is a long unaimed kick intended to move the ball as far as possible from the defender's goal. Due to the many skills centre-backs are required to possess in the modern game, many successful contemporary central-defensive partnerships have involved pairing a more physical defender with a defender who is quicker, more comfortable in possession and capable of playing the ball out from the back; examples of such pairings are John Terry and Ricardo Carvalho with Chelsea, Nemanja Vidić and Rio Ferdinand with Manchester United, or Giorgio Chiellini, Leonardo Bonucci and Andrea Barzagli with Juventus.[1][2]

During normal play, centre-backs are unlikely to score goals. However, when their team takes a corner kick or other set pieces, centre-backs may move forward to the opponents' penalty area; if the ball is passed in the air towards a crowd of players near the goal, then the heading ability of a centre-back is useful when trying to score. In this case, other defenders or midfielders will temporarily move into the centre-back positions.

In the modern game, most teams employ two or three centre-backs in front of the goalkeeper. The 4–2–3–1, 4–3–3, and 4–4–2 formations all use two centre-backs.

There are two main defensive strategies used by centre-backs: the zonal defence, where each centre-back covers a specific area of the pitch; and man-to-man marking, where each centre-back has the job of covering a particular opposition player.

Sweeper (libero)

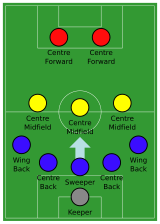

The 5–3–2 formation with a sweeper

The sweeper (or libero) is a more versatile centre-back who "sweeps up" the ball if an opponent manages to breach the defensive line.[3][4] This position is rather more fluid than that of other defenders who man-mark their designated opponents. Because of this, it is sometimes referred to as libero.[5][6]

Though sweepers may be expected to build counter-attacking moves, and as such require better ball control and passing ability than typical centre-backs, their talents are often confined to the defensive realm. For example, the catenaccio system of play, used in Italian football in the 1960s, employed a purely defensive sweeper who only "roamed" around the back line; Armando Picchi was a leading exponent of the more traditional variant of this role in Helenio Herrera's Grande Inter side.[7][8]

The more modern libero possesses the defensive qualities of the typical libero while being able to expose the opposition during counterattacks. The Fundell-libero has become more popular in recent time with the sweeper transitioning to the most advanced forward in an attack. This variation on the position requires great pace and fitness. While rarely seen in professional football, the position has been extensively used in lower leagues. Modern libero sit behind centre-backs as a sweeper before charging through the team to join in the attack.[9][10]

Some sweepers move forward and distribute the ball up-field, while others intercept passes and get the ball off the opposition without needing to hurl themselves into tackles. If the sweeper does move up the field to distribute the ball, they will need to make a speedy recovery and run back into their position. In modern football, its usage has been fairly restricted, with few clubs in the biggest leagues using the position.

The position is most commonly believed to have been pioneered by Franz Beckenbauer, Gaetano Scirea, and Elías Figueroa, although they were not the first players to play this position. Earlier proponents included Alexandru Apolzan, Ivano Blason, Velibor Vasović, and Ján Popluhár.[9][11][12][13][14][15][16] Other defenders who have been described as sweepers include Bobby Moore, Franco Baresi, Ronald Koeman, Fernando Hierro, Matthias Sammer, and Aldair, due to their ball skills, vision, and long passing ability.[9][11][12][17] Though it is rarely used in modern football, it remains a highly respected and demanding position.

A recent and successful use of the sweeper was made by Otto Rehhagel, Greece's manager, during UEFA Euro 2004. Rehhagel utilized Traianos Dellas as Greece's sweeper to great success, as Greece surprisingly became European champions.

Although this position has become largely obsolete in modern football formations, due to the use of zonal marking and the offside trap, certain defenders such as Leonardo Bonucci, Sergio Ramos, David Luiz and Daniele De Rossi have played a similar role as a ball-playing central defender in a 3–5–2 or 3–4–3 formation:[18] in addition to their defensive skills, their technique and ball-playing ability allowed them to advance into midfield after winning back possession, and function as a secondary playmaker for their teams.[18][19]

Some goalkeepers, who are comfortable leaving their goalmouth to intercept and clear through balls, and who generally participate more in play, such as René Higuita, Manuel Neuer, and Hugo Lloris, among others, have been referred to as sweeper-keepers.[20][21][22]

Full-back

Full-back Philipp Lahm (right) marks winger Nani.

The full-backs (the left-back and the right-back) take up the holding wide positions and traditionally stayed in defence at all times, until a set-piece. There is one full-back on each side of the field except in defences with fewer than four players, where there may be no full-backs and instead only centre-backs.[23]

In the early decades of football under the 2–3–5 formation, the two full-backs were essentially the same as modern centre-backs in that they were the last line of defence and usually covered opposing forwards in the middle of the field.[24]

WM formation of the 1920s showing three fullbacks, all in fairly central positions.

The later 3–2–5 style involved a third dedicated defender, causing the left and right full-backs to occupy wider positions.[25] Later, the adoption of 4–2–4 with another central defender[26] led the wide defenders to play even further over to counteract the opposing wingers and provide support to their own down the flanks, and the position became increasingly specialised for dynamic players who could fulfil that role as opposed to the central defenders who remained fairly static and commonly relied on strength, height and positioning.

In the modern game, full-backs have taken on a more attacking role than is the case traditionally, often overlapping with wingers down the flank.[27] Wingerless formations, such as the diamond 4–4–2 formation, demand the full-back to cover considerable ground up and down the flank. Some of the responsibilities of modern full-backs include:

- Provide a physical obstruction to opposition attacking players by shepherding them towards an area where they exert less influence. They may manoeuvre in a fashion that causes the opponent to cut in towards the centre-back or defensive midfielder with their weaker foot, where they are likely to be dispossessed. Otherwise, jockeying and smart positioning may simply pin back a winger in an area where they are less likely to exert influence.

- Making off-the-ball runs into spaces down the channels and supplying crosses into the opposing penalty box.

- Throw-ins are often assigned to full-backs.

- Marking wingers and other attacking players. Full-backs generally do not commit into challenges in their opponents' half. However, they aim to quickly dispossess attacking players who have already breached the defensive line with a sliding tackle from the side. Markers must however avoid keeping too tight on opponents or risk disrupting the defensive organisation.[28]

- Maintaining tactical discipline by ensuring other teammates do not overrun the defensive line and inadvertently play an opponent onside.

- Providing a passing option down the flank; for instance, by creating opportunities for sequences like one-two passing moves.

- In wingerless formations, full-backs need to cover the roles of both wingers and full-backs, although defensive work may be shared with one of the central midfielders.

- Additionally, attacking full-backs help to pin both opposition full-backs and wingers deeper in their own half with aggressive attacking intent. Their presence in attack also forces the opposition to withdraw players from central midfield, which the team can seize to its advantage.[29]

Due to the physical and technical demands of their playing position, successful full-backs need a wide range of attributes, which make them suited for adaptation to other roles on the pitch. Many of the game's utility players, who can play in multiple positions on the pitch, are natural full-backs. A rather prominent example is the Real Madrid full-back Sergio Ramos, who has played on the flanks as a full-back and in central defence throughout his career. In the modern game, full-backs often chip in a fair share of assists with their runs down the flank when the team is on a counter-attack. The more common attributes of full-backs, however, include:

- Pace and stamina to handle the demands of covering large distances up and down the flank and outrunning opponents.

- A healthy work rate and team responsibility.

- Marking and tackling abilities and a sense of anticipation.

- Good off-the-ball ability to create attacking opportunities for his team by running into empty channels.

- Dribbling ability. Many of the game's eminent attacking full-backs are excellent dribblers in their own right and occasionally deputise as attacking wingers.

- Player intelligence. As is common for defenders, full-backs need to decide during the flow of play whether to stick close to a winger or maintain a suitable distance. Full-backs that stay too close to attacking players are vulnerable to being pulled out of position and leaving a gap in the defence. A quick passing movement like a pair of one-two passes will leave the channel behind the defending full-back open. This vulnerability is a reason why wingers considered to be dangerous are double-marked by both the full-back and the winger. This allows the full-back to focus on holding his defensive line.[30]

Wing-back

The wing-back is a variation on the full-back, but with heavier emphasis on attack. This type of defender focuses more heavily on attack than defence, yet they must have the ability, when needed, to fall back and mark opposing players to lessen the threat of conceding a goal-scoring opportunity. Some formations have wing-back players that mainly focus on defending, and some that focus more on attack.

In the evolution of the modern game, wing-backs are the combination of wingers and full-backs. As such, it is one of the most physically demanding positions in modern football. Wing-backs are often more adventurous than full-backs and are expected to provide width, especially in teams without wingers. A wing-back needs to be of exceptional stamina, be able to provide crosses upfield and defend effectively against opponents' attacks down the flanks. A defensive midfielder is usually fielded to cover the advances of wing-backs.[31] It can also be occupied by wingers and side midfielders in a three centre-back formation, as seen by ex-Chelsea manager Antonio Conte.

See also

- Association football positions

References

^ Rob Bagchi (19 January 2011). "Judges have a blindspot when destroyers like Vidic play a blinder". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 February 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Paolo Bandini (13 June 2016). "Giorgio Chiellini: 'I have a strong temperament but off the pitch I am more serene'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

^ BBC Sports Academy

^ Evolution of the Sweeper

^ "DIZIONARIO DI ITALIANO DALLA A ALLA Z: Battitore". La Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 21 April 2016.

^ Damele, Fulvio (1998). Calcio da manuale. Demetra. p. 104.|access-date=requires|url=(help)

^ "La leggenda della Grande Inter" [The legend of the Grande Inter] (in Italian). Inter.it. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

^ Mario Sconcerti (23 November 2016). "Il volo di Bonucci e la classifica degli 8 migliori difensori italiani di sempre" (in Italian). Il Corriere della Sera. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

^ abc "BBC Football - Positions guide: Sweeper". BBC Sport. 1 September 2005. Retrieved 5 January 2008.

^ "Positions guide: Sweeper". BBC Sport. 1 September 2005. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

^ ab "Remembering Scirea, Juve's sweeper supreme". FIFA.com. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

^ ab "Franz Beckenbauer Biography". Retrieved 5 January 2015.

^ Rotting fruit, dying flowers The Guardian

^ Czechoslovakia World Cup Hero Jan Popluhar Dies Aged 75 Goal.com

^ VELIBOR VASOVIC The Independent

^ "Evolution of the Sweeper". Outsideoftheboot.com.

^ "Franchino (detto Franco) BARESI (II)". Retrieved 5 January 2015.

^ ab "Daniele De Rossi and the strange story of the Libero". forzaitalianfootball. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

^ "L'ANGOLO TATTICO di Juventus-Lazio - Due gol subiti su due lanci di Bonucci: il simbolo di una notte da horror" (in Italian). Retrieved 5 January 2015.

^ Tim Vickery (10 February 2010). "The Legacy of Rene Higuita". BBC. Retrieved 11 June 2014

^ Early, Ken (8 July 2014). "Manuel Neuer cleans up by being more than a sweeper". The Irish Times. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

^ Wilson, Jonathan (13 February 2014). "Tottenham's Hugo Lloris is Premier League's supreme sweeper-keeper". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

^ "Football is Coming Home to Die-Hard Translators". Article on the Translation Journal. 1 April 2008. Archived from the original on 27 March 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2008.

^ "England's Uniforms — Shirt Numbers and Names". Englandfootballonline.com. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

^ Ingle, Sean (15 November 2000). "Knowledge Unlimited: What a refreshing tactic". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

^ Lutz, Walter (11 September 2000). "The 4–2–4 system takes Brazil to two World Cup victories". FIFA. Archived from the original on 9 January 2006. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

^ Pleat, David (6 June 2007). "Fleet-of-foot full-backs carry key to effective attacking". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 December 2008. David Pleat explains in a Guardian article how full-backs aid football teams when attacking.

^ Pleat, David (18 February 2008). "How Gunners can avoid being pulled apart by Brazilian". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 December 2008. David Pleat explains the team effort in marking an attacking player stationed in the outside-wing position.

^ Pleat, David (18 May 2006). "How Larsson swung the tie". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 December 2008. David Pleat explains how the introductions of Barcelona full-back Juliano Belletti and striker Henrik Larsson in the 2006 UEFA Champions League Final improved Barcelona's presence in wide areas. Belletti eventually scored the winning goal for the final.

^ Pleat, David (31 December 2007). "City countered by visitors' Petrov defence". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 December 2008. David Pleat discusses the tactical implications of full-backs and other defenders marking wingers in a Guardian match analysis.

^ "Positions guide: Wingback". London: BBC Sport. 1 September 2005. Retrieved 21 June 2008.