Sudano-Sahelian architecture

The Great Mosque of Djenné, Mali (Malian).

Agadez Grand Mosque, Niger (Fortress style).

Larabanga Mosque, Ghana (Gur-Voltaic).

Sudano-Sahelian architecture refers to a range of similar indigenous architectural styles common to the African peoples of the Sahel and Sudanian grassland (geographical) regions of West Africa, south of the Sahara, but north of the fertile forest regions of the coast.

This style is characterized by the use of mudbricks and adobe plaster, with large wooden-log support beams that jut out from the wall face for large buildings such as mosques or palaces. These beams also act as scaffolding for reworking, which is done at regular intervals, and involves the local community. The earliest examples of Sudano-Sahelian style probably come from Jenné-Jeno around 250 BC, where the first evidence of permanent mudbrick architecture in the region is found.[1]

Contents

1 Difference between Savannah and Sahelian styles

2 Substyles

3 See also

4 Notes

5 Further reading

6 External links

Difference between Savannah and Sahelian styles

The earthen architecture in the Sahel zone region is noticeably different from the building style in the neighboring savannah. The "old Sudanese" cultivators of the savannah built their compounds out of several cone-roofed houses. This was primarily an urban building style, associated with centres of trade and wealth, characterised by cubic buildings with terraced roofs comprise the typical style.

They lend a characteristic appearance to the close-built villages and cities. Large buildings such as mosques, representative residential and youth houses stand out in the distance. They are landmarks in a flat landscape that point to a complex society of farmers, craftsmen and merchants with a religious and political upper class.

With the expansion of Sahelian kingdoms south to the rural areas in the savannas (inhabited by culturally or ethnically similar groups to those in the Sahel), the Sudano-Sahelian style was reserved for mosques, palaces, the houses of nobility or townsfolk (as is evident in the Gur-Voltaic style), whereas among commonfolk, there was a mix between either typically distinct Sudano-Sahelian styles for wealthier families, and older African roundhut styles for rural villages and family compounds.

Substyles

An ancestral Hausa multi-storey townhouse exhibiting the Tubali / Hausa architectural style, Agadez, central Niger.

The Sudano-Sahelian architectural style itself can be broken down into four smaller sub-styles that are typical of different ethnic groups in the region. The examples used here illustrate the construction of mosques as well as palaces, as the architectural style is concentrated around inland Muslim populations.

As with the people, many of these styles cross-pollinate and produce buildings with shared features. Any one of these styles is not exclusive to one particular modern countries borders, but are linked to the ethnicity of its builders or surrounding populations. For example, a Malian migrant community in traditionally Gur area may build in the style characteristic of their ancestral homeland, while neighbouring Gur buildings are built in the local style. These styles include:

Malian – of the various Manden groups of southern and central Mali. Characterized by the Great Mosque of Djenne and the Kani-Kombole Mosque of Mali.

Fortress style – predominantly used by the Zarma peoples of northern Nigeria and Niger, Hausa-Fulani, Tuareg and Arab mixed communities in Agadez, the Kanuri people of Lake Chad, and Songhai of northeastern Mali. Military aspect to construction of high protective compound walls built around a central courtyard. Minaret is the only structure with support beams showing. Characterized by the Sankore Mosque of Timbuktu, the tomb of Askia in Gao Mali, and the Agadez mosque of northern Niger.

Tubali – The characteristic Hausa architectural style predominant in North and Northwestern Nigeria, Niger, Eastern Burkina Faso, Northern Benin, and Hausa-predominant zango districts and neighbourhoods throughout West Africa. Characterised by its attention of stucco detail in abstract design and extensive use of parapets. One to two storey buildings. Examples in the architecture of the Yamma Mosque and old town of Zinder, The Hausa quarter of Agadez Niger, the Gidan Rumfa of Kano, and various Hausa districts across West Africa.

Volta basin – of the Gur and Manden groups of Burkina Faso, northern Ghana and northern Cote d'Ivoire. The most conservative of the three styles. A single courtyard, characterized by high white and black painted walls, inward curved turrets supporting an exterior wall, and a larger turret nearer the center. Characterized by the Larabanga mosque of Ghana and the Bobo-Dioulasso Grand Mosque.

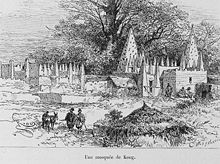

Historic mosque of Kong, now in Cote d'Ivoire, 1892

See also

- Sankore University

- Larabanga

- Agadez

- Great Mosque of Djenné

Notes

^ Brass, Mike (1998), The Antiquity of Man: East & West African complex societies.mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

Further reading

Aradeon, Suzan B. (1989), "Al-Sahili: the historian's myth of architectural technology transfer from North Africa", Journal des Africanistes, 59: 99–131, doi:10.3406/jafr.1989.2279.

Bourgeois, Jean-Louis; Pelos, Carollee (photographer); Davidson, Basil (historical essay) (1989), Spectacular vernacular : the adobe tradition, New York: Aperture Foundation, ISBN 0-89381-391-5. Second edition published in 1996.

Prussin, Labelle (1986), Hatumere: Islamic design in West Africa, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-03004-4.

Schutyser, S. (photographer); Dethier, J.; Gruner, D. (2003), Banco, Adobe Mosques of the Inner Niger Delta, Milan: 5 Continents Editions, ISBN 88-7439-051-3.

External links

- Tubali: hausa Architecture in Northern Nigeria

- Malian architecture

- Butabu, West Africa's Extraordinary Earthen Legacy

- Archnet Digital Library: Mud Mosques: The B&W prints