Gothic architecture

Top: Notre-Dame de Paris; Salisbury Cathedral: Center: buttresses of Cologne Cathedral, Facade statuary of Chartres Cathedral; Bottom: Windows of Sainte-Chapelle, Paris | |

| Years active | 12th–14th centuries |

|---|---|

| Influenced | Gothic Revival architecture |

Gothic architecture is a style that flourished in Europe during the High and Late Middle Ages. It evolved from Romanesque architecture and was succeeded by Renaissance architecture. Originating in 12th-century France, it was widely used, especially for cathedrals and churches, until the 16th century.

Its most prominent features included the use of the rib vault and the flying buttress, which allowed the weight of the roof to be counterbalanced by buttresses outside the building, giving greater height and more space for windows.[1] Another important feature was the extensive use of stained glass, and the rose window, to bring light and color to the interior. Another feature was the use of realistic statuary on the exterior, particularly over the portals, to illustrate biblical stories for the largely illiterate parishioners. These technologies had all existed in Romanesque architecture, but they were used in more innovative ways and more extensively in Gothic architecture to make buildings taller, lighter and stronger.

The first notable example is generally considered to be the Abbey of Saint-Denis, near Paris, whose choir and facade were reconstructed with Gothic features. The choir was completed in 1144. The style also appeared in some civic architecture in northern Europe, notably in town halls and university buildings. A Gothic revival began in mid-18th-century England, spread through 19th century Europe and continued, largely for ecclesiastical and university structures, into the 20th century.

Contents

1 Name

2 History

2.1 Origins – Early Gothic (1130–1200)

2.2 High Gothic (1200–1270)

2.3 Rayonnant Gothic (1250–1370s)

2.4 Flamboyant Gothic (1350–1550)

3 Elements of Gothic style

3.1 Plan

3.2 The pointed arch and the rib vault

3.3 Flying buttress

3.4 Height

3.5 Stained glass windows

3.6 Portals and the tympanum

3.7 Towers and spires

3.8 Sculpture and decoration

4 French Gothic

5 English Gothic

6 Northern European Gothic

7 Southern European Gothic

7.1 Spain and Portugal

7.2 Italy

8 Abbeys and monasteries

9 Civic architecture

9.1 University Gothic

10 Military architecture

11 Decline

12 Survival, rediscovery and revival

12.1 England

12.2 France

12.3 Germany and Russia

12.4 Italy

12.5 Canada

12.6 United States

12.7 Latin America, Asia and the Pacific

13 Influences

13.1 Political

13.2 Geographic

13.3 Possible Eastern influence

14 See also

15 Notes

15.1 Footnotes

15.2 Citations

16 References

16.1 Further reading

17 External links

Name

Gothic architecture was known during the period as opus francigenum ("French/Frankish work"),[2] The term "Gothic architecture" originated in the 16th century, and was originally very negative, suggesting barbaric. Giorgio Vasari used the term "barbarous German style" in his 1550 Lives of the Artists to describe what is now considered the Gothic style,[3] and in the introduction to the Lives he attributed various architectural features to "the Goths" whom he held responsible for destroying the ancient buildings after they conquered Rome, and erecting new ones in this style.[4]

History

Origins – Early Gothic (1130–1200)

The rebuilt ambulatory at the Abbey of Saint-Denis (1140–1144)

Exterior of Saint-Denis Basilica, with its three portals and remaining tower (1140–45)

The west front at Noyon Cathedral, begun 1145, showing influence of Saint-Denis

The apse of Noyon Cathedral (1155)

Laon Cathedral, begun 1155

Facade of Notre Dame de Paris, facade begun about 1200

The Gothic style originated in the Ile-de-France region of northern France in the first half of the 12th century. A new dynasty of French Kings, the Capetians, had subdued the feudal lords, and had become the most powerful rulers in France, with their capital in Paris. They allied themselves with the bishops of the major cities of northern France, and reduced the power of the feudal abbots and monasteries. Their rise coincided with an enormous growth of the population and prosperity of the cities of northern France. The Capetian Kings and their bishops wished to build new cathedrals as monuments of their power, wealth, and religious faith.[5]

The church which served as the primary model for the style was the Abbey of St-Denis, which underwent reconstruction by the Abbot Suger, first in the choir and then the facade (1140–44), Suger was a close ally and biographer of the French King, Louis VII, who was a fervent Catholic and builder, and the founder of the University of Paris. Suger remodeled the ambulatory of the Abbey, removed the enclosures that separated the chapels, and replaced the existing structure with imposing pillars and rib vaults. This created higher and wider bays, into which he installed larger windows, which filled the end of the church with light. Soon afterwards he rebuilt the facade, adding three deep portals, each with a tympanum, an arch filled with sculpture illustrating biblical stories. The new facade was flanked by two towers. He also installed a small circular rose window over the central portal. This design became the prototype for a series of new French cathedrals.[6]

Sens Cathedral (begun between 1135 and 1140) was the first Cathedral to be built in the new style (St. Denis was an abbey, not a Cathedral). Other versions of the new style soon appeared in Noyon Cathedral (begun 1150); Laon Cathedral (begun 1165); and the most famous of all, Notre-Dame de Paris, where construction had begun in 1160.[7]

The Gothic style was also adapted by some French monastic orders, notably the Cistercian order under Saint Bernard of Clairvaux It was used in an austere form without ornament at the new Cistercian Abbey of Fontenay (1139–1147) and the church of Clairvaux Abbey, whose site is now occupied by a French prison.[8]

The new style was also copied outside the Kingdom of France in the Duchy of Normandy. Early examples of Norman Gothic included Coutances Cathedral (1210–1274); Bayeux Cathedral (rebuilt from Romanesque style in 12th century), Le Mans Cathedral (rebuilt from Romanesque 12th century) and Rouen Cathedral. Through the rule of the Angevin dynasty, the new style was introduced to England and spread from there to Low Countries, Germany, Spain, northern Italy and Sicily.[1][9] The Gothic style did not immediately replace the Romanesque everywhere in Europe.[5] The Late Romanesque continued to flourish in the Holy Roman Empire under the Hohenstaufens and Rhineland.

High Gothic (1200–1270)

Overview of Chartres Cathedral (1194–1220)

Choir of Chartres Cathedral with the new, stronger four-part rib vault

Bourges Cathedral with flying buttresses (1195–1230)

Reims Cathedral from the northwest (1211–1345)

Facade of Amiens Cathedral (1220–1266)

Amiens Cathedral choir and altar

From the end of the 12th century until the middle of the 13th century, the gothic style spread from the Île-de-France to appear in other cities of northern France. New structures in the style included Chartres Cathedral (begun 1200); Bourges Cathedral (1195 to 1230), Reims Cathedral (1211–1275), and Amiens Cathedral (begun 1250);[10] At Chartres, the use of the flying buttresses allowed the elimination of the tribune level, which allowed much higher arcades and nave, and larger windows. The early type of rib vault used of Saint Denis and Notre Dame, with six parts, was modified to four parts, making it simpler and stronger. Amiens and Chartres were among the first to use the flying buttress; the buttresses were strengthened by an additional arch and with a supporting arcade, allowing even higher and walls and more windows. At Reims, the buttresses were given greater weight and strength by the addition of heavy stone pinnacles on top. These were often decorated with statues of angels, and became an important decorative element of the High Gothic style. Another practical and decorative element, the gargoyle, appeared; it was an ornamental rain spout which channeled the water from the roof away from the building. At Amiens, the windows of the nave were made larger, and an additional row of clear glass windows (the claire-voie) flooded the interior with light. The new structural technologies allowed the enlargement of the transepts and of the choirs at the east end of the cathedrals, creating the space for a ring of well-lit chapels. The transept of Notre-Dame was rebuilt with the new technology, and two spectacular rose windows added.[10]

Rayonnant Gothic (1250–1370s)

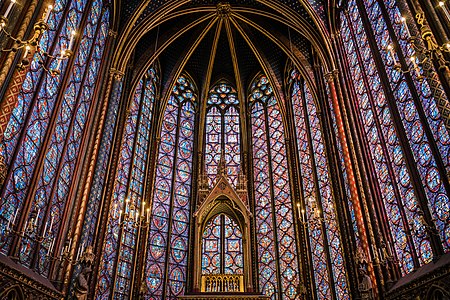

Windows of upper chapel of Sainte-Chapelle (1238–48)

Columns of exterior framework supporting the windows of Sainte-Chapelle

Rose window in north transept of Notre Dame Cathedral

Exterior of south rose window of Notre Dame Cathedral (about 1250)

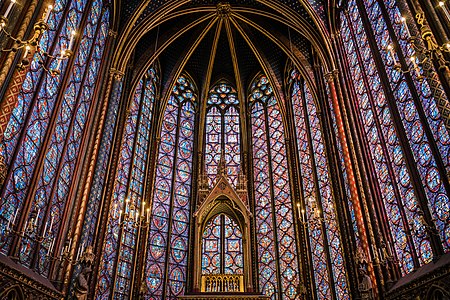

The next period was termed Rayonnant ("Radiant"), describing the tendency toward the use of more and more stained glass and less masonry in the design of the structure, until the walls seemed entirely made of glass. The most celebrated example was the chapel of Sainte-Chapelle, the chapel attached to the royal residence on the Palais de la Cité. An elaborate system of exterior columns and arches reduced the walls of the upper chapel to a thin framework for the enormous windows. The weight of each of the masonry gables above the archivolt of the windows also helped the walls to resist the thrust and to distribute the weight.[11]

Another landmark of the Rayonnant Gothic are the two rose windows on the north and south of the transept of Notre Dame Cathedral. Whereas earlier rose windows, like those of Amiens Cathedral, were framed by stone and occupied only a portion of the wall, these two windows, with a delicate lace-like framework, occupied the entire space between the pillars.[11]

Flamboyant Gothic (1350–1550)

The west front of Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes (1480)

The nave of Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes (1480–1551)

The rose window Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes. The sinuous lines of the window frame gave the style the name "Flamboyant" (1480)

Vault ceiling in the Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes

West facade, Rouen Cathedral (1509–1530)

Royal Monastery of Brou, Bourg-en-Bresse (1506—1532)

Facade of St. Anne's Church in Vilnius, Lithuania (1490s)

The Flamboyant Gothic style appeared in the second half of the 14th century. Its characteristic features were more exuberant decoration, as the nobles and wealthy citizens of mostly northern French cities competed to build more and more elaborate churches and cathedrals. It took its name from the sinuous, flame-like designs which ornamented windows. Other new features included the arc en accolade, a window decorated with an arch, stone pinnacles and floral sculpture. It also featured an increase in the number of nervures, or ribs, that supported and decorated each vault of the ceiling, both for greater support and decorative effect. Notable examples of Flamboyant Gothic include the western facade of Rouen Cathedral and Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes in Paris, both built in the 1370s; and the Choir of Mont Saint Michel Abbey (1448 c.).[12] Subsequently, the style spread to Northern Europe. Notable example of Flamboyant Gothic in the Baltic region includes the Brick Gothic Church of St. Anne in Vilnius (1490s).

Elements of Gothic style

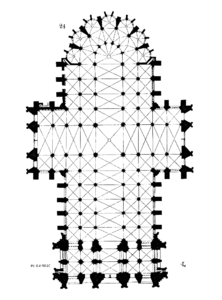

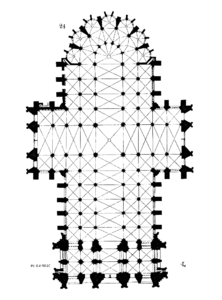

Plan

Plan of Chartres Cathedral (1194–1220)

Plan of a Gothic Cathedral

Plan of York Minster

Plan of Cologne Cathedral

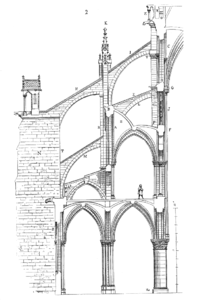

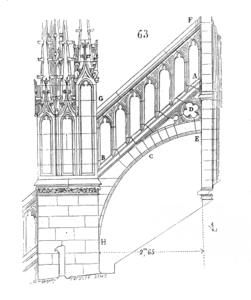

Cross section of the nave wall and buttresses of the Basilica of Saint Denis, by Eugene Viollet-le-Duc

The plan of the Gothic cathedral was based on the model of the ancient Roman basilica, which was a combined public market and courthouse; which was also the basis of the plan of the Romanesque cathedral. The cathedral is in the form of a Latin cross. The entrance is traditionally on the west end, has three portals decorated with sculpture, usually a rose window, and is flanked by two towers. The long nave, where the congregation worshiped, occupies the west end. This is usually divided from the nave by rows of pillars, which support the roof, flanked by one or two aisles, called collaérals. There are usually small chapels on the two sides, placed between the buttresses, which provide additional support to the walls.

The cathedral usually has a transept, a crossing, roughly in the middle, which sometimes projects outwards some distance, and in other cases, such as Notre-Dame, is minimal. The croisée or crossing of the transept, is the center of the church, and is surrounded by particularly massive pillars, which sometimes support a lantern tower, which brings light into the center of the cathedral. The north and south facades of the transept often feature rose windows, as at Notre Dame de Paris.

To the east of the transept is the choir, where the altar is located, where ceremonies take place, and where only the clergy was allowed. This space grew greatly in the 12th century, as ceremonies became more elaborate. Behind the choir is single or double a walkway called the ambulatory. At the eastern end of the church is the apse usually in the form of a half-circle, and the chevet. There is usually a chapel here dedicated to the Virgin Mary, which can be very large. Around chevet there are usually several other smaller chapels.[13]

The earlier Gothic cathedrals had four levels, from the floor to the roof. On the ground floor there were two rows grand arcades with large pillars, which received the weight of the vaults of the ceiling. Above these were the tribunes, a section of arched openings, giving more support. Above these was the triforium, a section of small arches. On the top level, just below the vaults, were the upper windows, the main source of light for the Cathedral. The lower walls were supported by massive contreforts or buttresses placed directly up against them, with pinnacles on top which provided additional weight.

Later, with the development of the flying buttress, the supports moved further away from the walls, and the walls were built much higher. Gradually the tribunes and the triforium disappeared, and the walls above the arcades were occupied almost entirely with stained glass.[14]

The eastern arm shows considerable diversity. In England it is generally long and may have two distinct sections, both choir and presbytery. It is often square ended or has a projecting Lady Chapel, dedicated to the Virgin Mary. In France the eastern end is often polygonal and surrounded by a walkway called an ambulatory and sometimes a ring of chapels called a "chevet". While German churches are often similar to those of France, in Italy, the eastern projection beyond the transept is usually just a shallow apsidal chapel containing the sanctuary, as at Florence Cathedral.[15][16]

Another characteristic feature of the Gothic style, domestic and ecclesiastical alike, is the division of interior space into individual cells according to the building's ribbing and vaults, regardless of whether or not the structure actually has a vaulted ceiling. This system of cells of varying size and shape juxtaposed in various patterns was again totally unique to antiquity and the Early Middle Ages and scholars, Frankl included, have emphasised the mathematical and geometric nature of this design. Frankl in particular thought of this layout as "creation by division" rather than the Romanesque's "creation by addition." Others, namely Viollet-le-Duc, Wilhelm Pinder, and August Schmarsow, instead proposed the term "articulated architecture."[17] The opposite theory as suggested by Henri Focillon and Jean Bony is of "spacial unification", or of the creation of an interior that is made for sensory overload via the interaction of many elements and perspectives.[18] Interior and exterior partitions, often extensively studied, have been found to at times contain features, such as thoroughfares at window height, that make the illusion of thickness. Additionally, the piers separating the isles eventually stopped being part of the walls but rather independent objects that jut out from the actual aisle wall itself.[19]

The pointed arch and the rib vault

Early six-part rib vaults at Notre-Dame de Paris (1182–1190)

Six-part rib vaults of choir of Canterbury Cathedral (about 1180)

Stronger four-part rib vaults at Rouen Cathedral (13th c.)

Nave of Cologne Cathedral (1248–1322)

Vaulted nave of Strasbourg Cathedral (1277–1318)

Net vault of Prague Cathedral (1356–1386)

Flamboyant rib vaults with ornamental ribs at Lady Chapel of Ely Cathedral (begun 1321)

Fan-shaped rib vaults at Peterborough Cathedral (1496–1508)

Both the pointed arch and the rib vault had been used in romanesque architecture, but Gothic builders refined them and used them to much greater effect. They made the structures lighter and stronger, and thus allowed the great heights and expanses of stained glass found in Gothic cathedrals.[1]

In Romanesque architecture, the rounded arches of the barrel vaults that supported the roof pressed directly down on the walls with crushing weight. This required massive columns, thick walls and small windows, and naturally limited the height of the building. The pointed or broken arch, introduced during the Romanesque period, was stronger, lighter, and carried the thrust outwards, rather than directly downwards.[1]

The rib vault took advantage of the strength of the pointed arch. The vault was supported by thin ribs or arches of stone, which reached downwards and outwards to cluster around supporting pillars along the inside of the walls. The earlier rib vaults, used at Notre Dame, Noyon, and Laon, were divided by the ribs into six compartments, and could only cross a limited space. In later cathedral construction, the design was improved, and the rib vaults had only four compartments, and could cover a wider span; a single vault could cross the nave, and fewer pillars were needed. The four-part vault was used at Amiens, Reims, and the other later cathedrals, and eventually at cathedrals across Europe.[1]

In the later period of the Gothic style, the rib vaults lost their elegant simplicity, and were loaded with additional ribs, sculptural designs, and sometimes pendants and other purely decorative elements.[1]

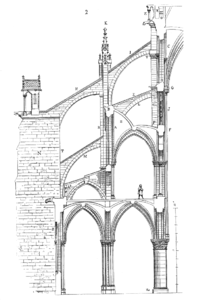

Flying buttress

Cross-section of the early supporting arches and buttresses of the nave of Notre-Dame Cathedral (13th century) drawn by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc.

At Notre-Dame de Paris, the massive buttresses counter the outward thrust from the rib vaults of the nave.

Later flying buttresses of the apse of Notre-Dame (14th century) reached 15 meters from the wall to the counter-supports.

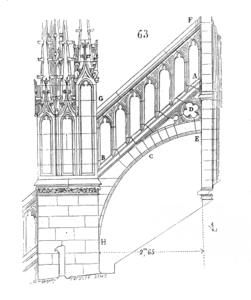

Flying buttresses of Amiens Cathedral (1220–1270)

The flying buttresses at Amiens combined carefully balanced weight with decoration (drawing by Eugene Viollet-le-Duc)

Another important feature of Gothic architecture was the flying buttress, designed to support the walls by means of arches connected to counter-supports outside the walls. Flying buttresses had existed in simple forms since Roman times, but the Gothic builders raised their use to a fine art, balancing the thrust from the roof inside against the counter-thrust of the buttresses. The earliest Gothic cathedrals, including Saint-Denis and Notre-Dame in its beginning stages, did not have flying buttresses. Their walls were supported by heavy stone abutments placed directly against the walls, The roof was supported by the ribs of the vaults, which were bundled with the columns below.

In the later 12th and early 13th century, the buttresses became more sophisticated. New arches carried the thrust of the weight entirely outside the walls, where it was met by the counter-thrust of stone columns, with pinnacles placed on top for decoration and for additional weight. Thanks to this system of external buttresses, the walls could be higher and thinner, and could support larger stained glass windows. The buttresses themselves became part of the decoration; the pinnacles became more and more ornate, becoming more and more elaborate, as at Beauvais Cathedral and Reims Cathedral. The arches had an additional practical purpose; they contained lead channels which carried rain water off the roof; it was expelled from the mouths of stone gargoyles placed in rows on the buttresses.[20]

In the late Gothic periods the buttresses became extremely ornate, with a large amount of non-functional decoration in the form of pinnacles, curving arches, counter-curves, statuary and ornamental pendants.

Height

Elevation of the early Noyon Cathedral (1150); Ground floor arcade of massive pillars supporting the roof; a second, smaller arcade, or tribune; the triforium, a narrow walkway; and (top) claire-voie with windows.

Elevation of Nave at Chartres Cathedral (1220). The tribune has disappeared and windows have gotten higher.

Amiens Cathedral; arcade, triforium and claire-voie. 42.30 meters (138.8 ft). (1220–1270)

The choir of Beauvais Cathedral 48.5 m (159 ft) high (1230–1569)

Nave of Milan Cathedral 45 m (148 ft) high (1389–1452)

An important characteristic of Gothic church architecture is its height, both absolute and in proportion to its width, the verticality suggesting an aspiration to Heaven. The increasing height of cathedrals over the Gothic period was accompanied by an increasing proportion of the wall devoted to windows, until, by the late Gothic, the interiors became like cages of glass. This was made possible by the development of the flying buttress, which transferred the thrust of the weight of the roof to the supports outside the walls. As a result, the walls gradually became thinner and higher, and masonry was replaced with glass. The four-part elevation of the naves of early Cathedrals such as Notre-Dame (arcade, tribune, triforium, claire-voie) was transformed in the choir of Beauvais Cathedral to very tall arcades, a thin triforium, and soaring windows up to the roof.[21]

Beauvais Cathedral reached the limit of what was possible with Gothic technology. A portion of the choir collapsed in 1284, causing alarm in all of the cities with very tall cathedrals. Panels of experts were created in Sienna and Chartres to study the stability of those structures.[22] Only the transept and choir of Beauvais were completed, and in the 21st century the transept walls were reinforced with cross-beams. No cathedral built since exceeded the height of the choir of Beauvais.[21]

A section of the main body of a Gothic church usually shows the nave as considerably taller than it is wide. In England the proportion is sometimes greater than 2:1, while the greatest proportional difference achieved is at Cologne Cathedral with a ratio of 3.6:1. The highest internal vault is at Beauvais Cathedral at 48 metres (157 ft).[15]

Stained glass windows

Abbey of Saint-Denis, Abbot Suger represented at feet of Virgin Mary (12th century)

South transept rose window of Chartres Cathedral (1221–1230)

Detail of the Apocalypse window, Bourges Cathedral, early 13th century

South Oculus of Canterbury Cathedral. It contains fourteen of the original glass sections from the 12th century

The Rayonnant north rose window of Notre-Dame de Paris (about 1250)

One of the most prominent features of Gothic architecture was the use of stained glass window, which steadily grew in height and size and filled cathedrals with light and color. Historians including Viollet-le-Duc, Focillon, Aubert, and Max Dvořák contended that this is one of the most universal features of the Gothic style.[23]

Religious teachings in the Middle Ages, particularly the writings of Religious Pseudo-Dionysius, a 6th-century mystic whose book, The Celestial Hierarchy, was popular among monks in France, taught that all light was divine. When the Abbot Suger ordered the reconstruction of the Basilica of Saint Denis, he instructed that the windows in the choir admit as much light as possible.

Many earlier Romanesque churches had stained glass windows, and many had round windows, called oculi, but these windows were necessarily small, due to the thickness of the walls. The primary interior decorations of Romanesque cathedrals were painted murals. In the Gothic period, the improvements in rib vaults and flying buttresses allowed Cathedral walls to be higher, thinner and stronger, and windows were consequently considerably larger, The windows of churches in the late Gothic period, such as Sainte Chapelle in Paris, filled the entire wall between the ribs of stone. Enormous windows were also an important element of York Minster and Gloucester Cathedral.[16]

The main threat to cathedral windows was the wind; frames had to be extremely strong. The early windows were fit into openings cut into the stone. The small pieces of colored glass were joined together with pieces of lead, and then their surfaces were painted with faces and other details. and then the windows were mounted in the stone frames. Thin vertical and horizontal bars of iron, called vergettes or barlotierres, were placed inside the window to reinforce the glass.

The stories told in the glass were usually episodes from the Bible, but they also sometimes illustrated the professions of the guilds which had funded the windows, such as the drapers, stonemasons or the barrel-makers.[24]

Much of the stained glass in Gothic cathedrals today dates from later restorations, but a few cathedrals, notably Chartres Cathedral and Bourges Cathedral, still have many of their original windows.[24]

Portals and the tympanum

North portal of Basilica of St Denis, with early tympanum and columns made of elongated figures (1135–1140)

Day of Judgement tympanum at Amiens Cathedral (1220–1270), the prototype for other high Gothic portals.

Portals and tympanum of Strasbourg Cathedral (Begun 1176)

Westminster Abbey north portal (begun 1245)

Early Gothic Cathedrals traditionally have their main entrance at the western end of the church, opposite the choir. Based on the model of the Basilica of Saint Denis and Notre-Dame de Paris, there are usually three doorways with pointed arches, richly filled with sculpture. The tympanum, or arch, over each doorway is filled with realistic statues illustrating biblical stories, and the columns between the doors are often also crowded with statuary. Following the example of Amiens, the tympanum over the central portal traditionally depicted the Last Judgement, the right portal showed the coronation of the Virgin Mary, and the left portal showed the lives of saints who were important in the diocese.[25]

The iconography of the sculptural decoration on the facade was not left to the artists. An edict of the Second Council of Nicaea in 787 had set the rules: "The composition of religious images is not to be left to the inspiration of artists; it is derived from the principles put in place by the Catholic Church and religious tradition. Only the art belongs to the artist; the composition belongs to the Fathers."[26]

The portals and interiors were much more colorful than they are today. Each sculpture on the tympanum and in the interior was painted by the peintre imagier, or image painter, following a system of colors codified in the 12th century; yellow, called gold, symbolized intelligence, grandeur and virtue; white, called argent, symbolized purity, wisdom, and correctness; black, or sable, meant sadness, but also will; green, or sinopole, represented hope, liberty and joy; red or guelues meant charity or victory; blue, or azure symbolized the sky, faithfulness and perseverance; and violet, or pourpre, was the color of royalty and sovereignty.[27]

Towers and spires

Laon Cathedral, with five towers (1160–1230)

The Abbey of Saint-Étienne, Caen rebuilt from Romanesque to Gothic, has nine towers (13th century)

Basilica of Notre-Dame de l'Épine, near Verdun, (1420) an example of Flamboyant Gothic towers

Towers of Rouen Cathedral (15th and 16th centuries)

Tower of Salisbury Cathedral, the tallest in Britain (1220v1258)

The plan for the Basilica of Saint-Denis called for two towers of equal height on the west facade, and this general plan was copied at Notre-Dame and most of the early cathedrals. The towers of Notre-Dame de Paris, 69 meters (226 ft) tall, were intended to be seen throughout the city; they were the tallest towers in Paris until the completion of the Eiffel Tower in 1889. An informal but vigorous competition began in northern France for the tallest Cathedral towers.[28]

To make the churches taller and more prominent, and visible from a distance, heir builders often added a flèche, a spire usually made of wood and covered with lead, to the top of each tower, or, as in Notre-Dame de Paris, in the center of the transept. Later in the Gothic period, more massive towers were constructed over the transept, rivaling or exceeding in height the towers of the facade.

The towers were usually the last part of the Cathedral to be constructed. They were often built many years or decades after the rest of the building. Sometimes, by the time the towers were built, the plans had changed, or the money had run out. As a result, some Gothic cathedrals had just one tower, or two towers of different heights or styles. On the other hand, Laon Cathedral, begun just before Notre-Dame, boasted five towers; two on the facade, two on the transept, and a central lantern. An additional two were planned but not built. The Abbey of Saint-Étienne, Caen originally built in the Romanesque style, was rebuilt with nine Gothic towers in the 13th century.

The informal competition for the tallest church in Europe went on throughout the Gothic period, sometimes with disastrous results. Beauvais Cathedral had the tallest tower (153 meters or 502 feet), completed in 1569, for a brief time, until its tower collapsed in the wind in 1573. Lincoln Cathedral (159.7 meters or 524 feet) also had the record from 1311 until 1549 until its tower also collapsed. Today the tallest cathedral tower in France is Rouen Cathedral, and Cologne Cathedral (151.0 meters or 495 feet) is the tallest cathedral in Europe.

The Gothic Old St Paul's Cathedral (1087–1314) had been the tallest cathedral in England until it was destroyed by the Great Fire of London in 1666. Today the tallest combined Gothic tower and spire in the UK belongs to Salisbury Cathedral, (123 meters or 404 feet), built 1220–1258.

In Italy, the tower, if present, is almost always detached from the building, as at Florence Cathedral, and is often from an earlier structure.[citation needed] In France and Spain, two towers on the front is the norm. In England, Germany and Scandinavia this is often the arrangement, but an English cathedral may also be surmounted by an enormous tower at the crossing. Smaller churches usually have just one tower, but this may also be the case at larger buildings, such as Salisbury Cathedral or Ulm Minster in Ulm, Germany, completed in 1890 and possessing the tallest spire in the world,[29] slightly exceeding that of Lincoln Cathedral, the tallest spire that was actually completed during the medieval period, at 160 metres (520 ft).[30]

Sculpture and decoration

Statues of Saints are literally "pillars of the church", supporting the portal of Chartres Cathedral.

The martyr Saint Denis, holding his head, over the Portal of the Virgin (Notre-Dame de Paris)

The serpent tempts Adam and Eve; part of the Last Judgement on the central portal of west facade of Notre-Dame de Paris

Archangel Michael and Satan weighing souls during the Last Judgement (Notre-Dame de Paris central portal, west facade)

A stryge on west facade of Notre-Dame de Paris

Gargoyles were the rainspouts of Notre-Dame de Paris

Chimera on Notre-Dame de Paris west facade

Gargoyle on Brussels Town Hall

Gargoyle on Siena Cathedral (13th century)

Labyrinth at Chartres Cathedral

The exteriors and interiors of Gothic cathedrals, particularly in France, were lavishly ornamented with sculpture and decoration on religious themes, designed for the great majority of parishioners who could not read. They were described as "Books for the poor." To add to the effect, all of the sculpture on the facades was originally painted and gilded.[31]

Each feature of the Cathedral had a symbolic meaning. The main portals at Notre Dame de Paris, for instance, represented the entrance to paradise, with the last judgement depicted on the tympanum over the doors, showing Christ surrounded by the apostles, and by the signs of the zodiac, representing the movements of the heavens. The columns below the tympanum are in the form of statues of saints, literally reprinting them as "the pillars of the church." [32]

Each Saint had his own symbol; a winged lion stood for Saint Mark; an eagle with four wings meant Saint John the Apostle, and a winged bull symbolized Saint Luke. Sculpted angels had specific functions, sometimes as heralds, blowing trumpete, or holding up columns, as guardian angels; or holding crowns of thorns or crosses, as symbols of the crucifixion of Christ, or waving a container with incense, to illustrate theirfunction at the throne of God. Floral and vegetal decoration was also very common, representing the Garden of Eden; grapes represented the wines of Eucharist.[32]

The tympanum over the central portal on the west facade of Notre Dame de Paris vividly illustrates the Last Judgement, with figures of sinners being led off to hell, and good Christians taken to heaven. The sculpture of the right portal shows the coronation of the Virgin Mary, and the left portal shows the lives of saints who were important to Parisians, particularly Saint Anne, the mother of the Virgin Mary.[25]

The exteriors of cathedrals and other Gothic churches were also decorated with sculptures of a variety of fabulous and frightening grotesques or monsters. These included the chimera, a mythical hybrid creature which usually had the body of a lion and the head of a goat, and the Strix or stryge, a creature resembling an owl or bat, which was said to eat human flesh. The strix appeared in classical Roman literature; it was described by the Roman poet Ovid, who was widely read in the Middle Ages, as a large-headed bird with transfixed eyes, rapacious beak, and greyish white wings.[33] They were part of the visual message for the illiterate worshipers, symbols of the evil and danger that threatened those who did not follow the teachings of the church.[34]

The gargoyles, which were added to Notre Dame in about 1240, had a more practical purpose. They were the rain spouts of the cathedral, designed to divide the torrent of water which poured from the roof after rain, and to project it outwards as far as possible from the buttresses and the walls and windows so that it would not erode the mortar binding the stone. To produce many thin streams rather than a torrent of water, a large number of gargoyles were used, so they were also designed to be a decorative element of the architecture. The rainwater ran from the roof into lead gutters, then down channels on the flying buttresses, then along a channel cut in the back of the gargoyle and out of the mouth away from the cathedral.[31]

Many of the statues, particularly the grotesques, were removed from facade in the 17th and 18th century, or were destroyed during the French Revolution. They were replaced with figures in the Gothic style, designed by Eugene Viollet-le-Duc, during the 19th century restoration. Similar figures appear on the other Gothic Cathedrals of France.

Another common feature of Gothic cathedrals in France was a labyrinth or maze on the floor of the nave near the choir, which symbolized the difficult and often complicated journey of a Christian life before attaining paradise. Most labyrinths were removed by the 18th century, but a few, like the one at Amiens Cathedral, have been reconstructed, and the labyrinth at Chartres Cathedral still exists essentially in its original form.[35]

French Gothic

Coutances Cathedral in Normandy (1210–1274)

Bayeux Cathedral in Normandy (1180–1350)

Interior of Auxerre Cathedral in Burgundy (1215–1233)

Albi Cathedral, originally begun as a fortress, in Southwest France (1282–1480)

Polychrome interior of Albi Cathedral (1282–1480)

Toulouse Cathedral (13th century)

The Palm Tree of the Jacobins church, 28 meters high (Toulouse, 1292)

From the 12th century onwards, the Gothic style spread from Northern France to other regions of France and gradually to the rest of the Europe. It was often carried by the highly skilled craftsmen who had trained in the Ile-de-France and then carried their crafts to other cities. The style was adapted to local styles and materials.

In Normandy, the new naves were usually very long, sometimes more than one hundred meters, and, from the long Romanesque tradition, the walls were thicker than in northern France, and had shorter buttresses. The interiors were narrower than in the north, and were given a strong sense of verticality by long and narrow bays and lancet arches. Rose windows were rare, replaced on the exterior by a large bay in tiers point. The facades had less sculptural decoration; decoration in the interior was largely in geometric forms. Norman Gothic also usually featured a profusion of towers, lanterns and spires; spires and spires sometimes were seventy meters high. Bayeux Cathedral, Rouen Cathedral, and Coutances Cathedral are notable examples of Norman Gothic.[36]

In Burgundy, which had a long Romanesque style tradition, a lantern tower was often included, and cathedrals often had a narrow passage the length of the cathedral at the level of the stained glass windows. as in Auxerre Cathedral.

In the Southwest of France, the walls were thicker, with narrow openings, and doubled with arches. The flying buttress were rarely used, replaced by heavy abutments with chapels between.[36]

The south of France had its own distinct variation of the Gothic style : the Southern French Gothic. The Gothic cathedrals were often built with brick and tile rather than stone. They generally had thick walls and narrow windows, and were braced by heavy abutments rather than flying buttresses. The form of the tower of the basilica of Saint-Sernin was copied by several cathedrals in the south, while the old nave of Toulouse Cathedral (1210-1220) gave the model of the single nave which was generally used in Southern French Gothic architecture (although some churches had two or three naves of equal height). Some Gothic cathedrals in the Midi took unusual form; the Cathedral of Albi (1282–1480) was originally built as fortress, then converted to a cathedral. Albi Cathedral has another very distinctive feature; a colorful interior and painted ceiling [36].

In the Jacobins church of Toulouse, the grafting of a single apse of polygonal plan on a church with two vessels gave birth to a starry vault whose complex organization anticipated more than a century on the flamboyant Gothic. Tradition refers to this masterpiece as "palm tree", because the veins gush out of the smooth shaft of the column like palm trees[37].

The facade of Toulouse Cathedral is unusual; it is the combination of two unfinished cathedral buildings, begun in the 13th century and finally put together. Toulouse Cathedral has no flying buttresses; it is supported by massive contreforts the height of the building, with chapels between.

English Gothic

12th century choir of Canterbury Cathedral (Early English Gothic)

Choir of Salisbury Cathedral (1220–1258) (Early English Gothic)

West front of York Minster (Decorated Gothic)

Gloucester Cathedral (Perpendicular Gothic) (1351–1377)

Fan vaults with pendants at the Henry VII Chapel of Westminster Abbey (Perpendicular Gothic) (1503)

The Gothic style was imported very early into England, in part due to the close connection with the Duchy of Normandy, which until 1204 was still ruled by the Kings of England. The first period is generally called early English Gothic, and was dominant from about 1180 to 1275. The first part of major English cathedral to feature the new style was the choir of Canterbury Cathedral, begun about 1175. It was created by a French master builder, William of Sens. He added several original touches, including colored marble pavement, double columns in the arcades, and engaged slender colonettes which reached up to the vaults, borrowed from the design of Laon Cathedral.[38]Westminster Abbey was rebuilt from 1245 to 1517. Salisbury Cathedral (1220–1320) is also a good example of early Gothic, with the exception of its tower and spire, which were added in 1320.[39]

The second period of English Gothic is known as Decorated Gothic. It is customarily divided into two the "Geometric" style (1250–90) and the "Curvilinear" style (1290–1350), and it is similar to the French Rayonnant style, with an emphasis on curvilinear forms, particularly in the windows. This period saw detailed stone carving reach its peak, with elaborately carved windows and capitals, often with floral patterns, or with an accolade, a carved arch over a window decorated with pinnacles and a fleuron, or carved floral element.[39]

The rib vaults of the Decorated Gothic became extremely ornate, with a profusion of ribs which were purely ornamental. The vaults were often decorated with hanging stone pendants. The columns also became more ornamental, as at Peterborough Cathedral, with ribs spreading upward.[39]

The Perpendicular Gothic (c. 1380–1520) was final phase of English Gothic, lasting into the 16th century. As the name suggests, its emphasis was on clear horizontal and vertical lines, meeting at right angles. Columns extended upwards all the way to the roof, giving the interior the appearance of a cage of glass and stone, as in the nave of Gloucester Cathedral. The Tudor Arch appeared, wider and lower and often framed by moldings, which was used to create larger windows and to balance the strong vertical elements. The design of the rib vaults became even more complex, including the fan vault with pendants used in the Henry VII chapel at Westminster Abbey (1503–07).[39][15][40]

A distinctive characteristic of English cathedrals is their extreme length, and their internal emphasis upon the horizontal, which may be emphasised visually as much or more than the vertical lines. Each English cathedral (with the exception of Salisbury) has an extraordinary degree of stylistic diversity, when compared with most French, German and Italian cathedrals. It is not unusual for every part of the building to have been built in a different century and in a different style, with no attempt at creating a stylistic unity. Unlike French cathedrals, English cathedrals sprawl across their sites, with double transepts projecting strongly and Lady Chapels tacked on at a later date, such as at Westminster Abbey. In the west front, the doors are not as significant as in France, the usual congregational entrance being through a side porch. The West window is very large and never a rose, which are reserved for the transept gables. The west front may have two towers like a French Cathedral, or none. There is nearly always a tower at the crossing and it may be very large and surmounted by a spire. The distinctive English east end is square, but it may take a completely different form. Both internally and externally, the stonework is often richly decorated with carvings, particularly the capitals.[15][40]

Northern European Gothic

Interior of Liebfrauenkirche in Trier (c. 1233–1283)

Cologne Cathedral, Germany (1248–1473)

Nave of Cologne Cathedral (1248–1473)

St. Andrew's Church, Hildesheim, Germany (c. 1389–1504)

St. Wenceslas Chapel in Prague Cathedral, Czech Rep. (1356–1367)

Karlstein Castle in Bohemia (1357–1367)

St. Stephen's Cathedral, Vienna, Austria (1339–1365)

St. Mary's Basilica, Kraków, Poland (1290–1365)

St. Mary's Church, Gdańsk, Poland (1379–1502)

Wooden ceiling of the Brabantine Gothic Grote Kerk, Haarlem in Netherlands (c. 1479)

Brabantine Gothic Church of Our Blessed Lady of the Sablon in Brussels (15th century)

Between the 13th and 16th centuries, Gothic cathedrals were constructed in most of the major cities of northern Europe. For the most part, they followed the French model, but with variations depending upon local traditions and the materials available. The first Gothic churches in Germany were built from about 1230. They included Liebfrauenkirche ( ca. 1233–1283) in Trier, claimed to be the oldest Gothic church in Germany,[41] and Freiburg Cathedral, which was built in three stages, the first beginning in 1120, though only the foundations of the original cathedral still exist. It is noted for its 116-metre tower, the only Gothic church tower in Germany that was completed in the Middle Ages (1330).

Prague, in the region Bohemia within the Holy Roman Empire, was another flourishing center for Gothic architecture. Charles IV of Bohemia was both King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Empire, and he had monumental tastes. He began construction of Prague's St. Vitus Cathedral in the Gothic style in 1344, as well as a Gothic palace, Karlstein Castle in Central Bohemia, and Gothic buildings for the new University of Prague. The nave of Prague Cathedral featured the filet vault, a decorative type of vault in which the ribs criss-crossed in a mesh pattern, similar to the vaults of Bristol Cathedral and other English churches. His other Gothic projects included the lavishly decorated Chapel of the Holy Cross inside Karlstein Castle (1357–1367), and the choir of Aachen Cathedral begun in 1355, which was built on the model of Sainte-Chapelle in Paris.[42] Gothic architecture in Germany and the kingdoms of the Holy Roman Empire generally followed the French formula, but the towers were much taller and, if completed, were often surmounted by enormous openwork spires. The distinctive character of the interior of German Gothic cathedrals is their breadth and openness. German and Czech cathedrals, like the French, tend not to have strongly projecting transepts. There are also many hall churches (Hallenkirchen) without clerestory windows.[15][16]Cologne Cathedral is after Milan Cathedral the largest Gothic cathedral in the world. Construction began in 1248 and took, with interruptions, until 1880 to complete – a period of over 600 years. It is 144.5 metres long, 86.5 m wide and its two towers are 157 m tall.[43]

Brick Gothic (German: Backsteingotik, Polish: Gotyk ceglany) is a specific style common in Northern Europe, especially in Northern Germany, Poland and in the regions around the Baltic Sea without natural rock resources. Prime examples of brick gothic include St. Mary's Church, Gdańsk (1379–1502),[44]St. Mary's Basilica, Kraków (1290–1365) and Malbork Castle (13th century).

St. Stephen's Cathedral, Vienna (1339–1365) has the distinctive feature of a polychrome roof. Another regional variation is the Brabantine Gothic a style found in Belgium and the Netherlands. It is characterized by using light-colored sandstone or limestone, which allowed rich detailing but was prone to erosion. Features included columns with sculpted cabbage-like foliage, arched windows whose points came right up into the vaults. and, sometimes, a wooden ceiling. Examples include Grote Kerk, Haarlem, in Haarlem, the Netherlands, originally built as a Catholic Cathedral, now a Protestant church, and the Church of Our Blessed Lady of the Sablon in Brussels (15th century).

Southern European Gothic

Spain and Portugal

León Cathedral (1205–1472)

Toledo Cathedral (1227–1493)

Burgos Cathedral (1221–1260)

Valencia Cathedral (13th–15 c.)

Evora Cathedral, Évora, Portugal (1280–1340)

Gothic nave of Évora Cathedral, Portugal, leads to a Baroque chapel (1280–1340)

Strikingly different variations of the Gothic style appeared in southern Europe, particularly in Spain and Portugal. Important examples of Spanish Gothic include Toledo Cathedral, León Cathedral, and Burgos Cathedral.

The distinctive characteristic of Gothic cathedrals of the Iberian Peninsula is their spatial complexity, with many areas of different shapes leading from each other. They are comparatively wide, and often have very tall arcades surmounted by low clerestories, giving a similar spacious appearance to the Hallenkirche of Germany, as at the Church of the Batalha Monastery in Portugal. Many of the cathedrals are completely surrounded by chapels. Like English cathedrals, each is often stylistically diverse. This expresses itself both in the addition of chapels and in the application of decorative details drawn from different sources. Among the influences on both decoration and form are Islamic architecture and, towards the end of the period, Renaissance details combined with the Gothic in a distinctive manner. The West front, as at Leon Cathedral, typically resembles a French west front, but wider in proportion to height and often with greater diversity of detail and a combination of intricate ornament with broad plain surfaces. At Burgos Cathedral there are spires of German style. The roofline often has pierced parapets with comparatively few pinnacles. There are often towers and domes of a great variety of shapes and structural invention rising above the roof.[15]

In the territories under the Crown of Aragon (Aragon, Catalonia, Roussillon in France, the Balearic Islands, the Valencian Community, among others in the Italian islands), the Gothic style suppressed the transept and made the side-aisles almost as high as the main nave, creating wider spaces, and with few ornaments. There are two different Gothic styles in the Aragonese lands: Catalan Gothic and Valencian Gothic, which are different from those in the Kingdom of Castile and France.

The most important samples of Catalan Gothic style are the cathedrals of Girona, Barcelona, Perpignan and Palma (in Mallorca), the basilica of Santa Maria del Mar (in Barcelona), the Basílica del Pi (in Barcelona), and the church of Santa Maria de l'Alba in Manresa.

The most important examples of Valencian Gothic style in the old Kingdom of Valencia are the Valencia Cathedral, Llotja de la Seda (Unesco World Heritage site), Torres de Serranos, Torres de Quart, Monastery of Sant Jeroni de Cotalba, in Alfauir, Palace of the Borgias in Gandia, Monastery of Santa María de la Valldigna, Basilica of Santa Maria, in Alicante, Orihuela Cathedral, Castelló Cathedral and El Fadrí, Segorbe Cathedral, etc.

Italy

Siena Cathedral (1215–1263)

Interior of Siena Cathedral (1215–1263)

Orvieto Cathedral (1290–1591)

Nave of Orvieto Cathedral (begun 1290)

Florence Cathedral (1296–1436)

Pulpit of Pisa Cathedral, by Giovanni Pisano (1302–1310)

Santa Maria della Spina (about 1323)

Milan Cathedral (1386–1510 – facade from 19th century)

Doges Palace (1424-1442)

Italian Gothic architecture went its own particular way, departing from the French model. It was influenced by other styles, notably the Byzantine style introduced in Ravenna. Major examples include Milan Cathedral, the Orvieto Cathedral, and particularly Florence Cathedral, before the addition of the Duomo in the Renaissance.[39]

The Italian style was influenced by the materials available in the different regions; marble was available in great quantities in Tuscany, and was lavishly used in churches; it was scarce in Lombardy, and brick was used instead. But many of the architectural elements were used apparently mainly to be different from the French style.[45]

The Cistercian monastic order introduced some of the first Gothic churches into Italy, in Fossanova Abbey (consecrated 1208) and the Casamari Abbey (1203–1217). They followed the basic plan of the Gothic Cistercian churches of Burgundy, particularly Cîteaux Abbey.[46]

The Italian plan is usually regular and symmetrical, Italian cathedrals have few and widely spaced columns. The proportions are generally mathematically equilibrated, based on the square and the concept of "armonìa", and except in Venice where they loved flamboyant arches, the arches are almost always equilateral. Italian Gothic cathedrals often retained Romanesque features; the nave of Orvieto Cathedral had Romanesque arches and vaults.

Italian Cathedrals also offered a variety of plans; Florence Cathedral (begun 1246) had a rectangular choir, based on the Cistercian model, but was designed to have three wings with polygonal chapels. Italian Gothic cathedrals were general not as tall as those in France; they rarely used flying buttresses, and generally had only two levels, an arcade and a claire-voie with small windows; but Bologna Cathedral (begun in 1388), rivaled Bourges Cathedral in France in height. The smallest notable Italian Gothic church is Santa Maria della Spina in Pisa (about 1330), which resembles a Gothic jewel box.[46]

A distinctive characteristic of Italian Gothic is the use of polychrome decoration, both externally as marble veneer on the brick façade and internally where the arches are often made of alternating black and white segments. The columns were sometimes painted red, and the walls were decorated with frescoes and the apse with mosaic. Italian cathedral façades are often polychrome and may include mosaics in the lunettes over the doors. The façades have projecting open porches and ocular or wheel windows rather than roses, and do not usually have a tower. The crossing is usually surmounted by a dome. There is often a free-standing tower and baptistery. The eastern end usually has an apse of comparatively low projection. The windows are not as large as in northern Europe and, although stained glass windows are often found, the favourite narrative medium for the interior is the fresco.[15] The facade of Orvieto Cathedral, begun in 1310, is a striking example of mosaic decoration. Another innovation of Italian Gothic is the bronze doorway covered with sculpture; the most famous examples are the doors of the Baptistry of Florence, by Andrea Pisano (1330–1336).[47]

Italian Gothic cathedrals did not have the elaborate sculptural tympanums over the entrances of French cathedrals, but they had abundant realistic sculptural decoration. Some of the finest work was done by Nicola Pisano at the Baptistery of Pisa Cathedral (1259–60), and in Siena Cathedral; and by his son Giovanni Pisano on the west facade of Pisa Cathedral (1284–85).[48]

Abbeys and monasteries

Abbey of Saint-Ouen, Rouen (1318–1537)

Mont Saint Michel Abbey church (Choir completed 1228)

Abbey of Saint-Remi, Reims (1170–80)

Batalha Monastery, Portugal (1386–1517)

While cathedrals were the most prominent structures in the Gothic style, Gothic features were also built for many monasteries across Europe. Prominent examples were built by the Benedictines in England, France, and Normandy. They were the builders of the Abbey of St Denis, and Abbey of Saint-Remi in France. Later Benedictine projects (constructions and renovations) include Rouen's Abbey of Saint-Ouen, the Abbey La Chaise-Dieu, and the choir of Mont Saint-Michel in France.

English examples are Westminster Abbey, originally built as a Benedictine order monastic church; and the reconstruction of the Benedictine church at Canterbury. The Cistercians spread the style as far east and south as Poland and Hungary.[49] Smaller orders such as the Carthusians and Premonstratensians also built some 200 churches, usually near cities.[50] The Franciscans and Dominicans also carried out a transition to Gothic in the 13th and 14th centuries. The Teutonic Order, a military order, spread Gothic art into Pomerania, East Prussia, and the Baltic region.[51]

The earliest example of Gothic architecture in Germany is Maulbronn Monastery, a Romanesque Cistercian abbey in southwest Germany whose narthex was built in the early 12th century by an anonymous architect.[52]

Batalha Monastery (1386–1517) is a Dominican monastery in Batalha, Portugal. The monastery was built in the Flamboyant Gothic style to thank the Virgin Mary for the Portuguese victory over the Kingdom of Castile in the Battle of Aljubarrota in 1385.

Civic architecture

The Palais de la Cité in Paris (begun 1119) which included the royal residence and later Sainte-Chapelle (1238–1248)

Gothic rib vaults of the hall of men at arms of the Conciergerie (1302)

The façade of the Palais des Papes in Avignon (1252–1364)

Brussels Town Hall (15th C.)

Venetian Gothic. The Doge's Palace in Venice (1340–1442)

Silk Exchange in Valencia, Spain (1482–1548)

Hall of Columns of the Silk Exchange in Valencia

Palace of the Kings of Navarre in Olite, Spain (1269–1512)

Gallery of Palau de la Generalitat in Barcelona, Spain (1403)

Vladislav Hall in Prague, Czech Rep. (1493–1502)

The Great Gatehouse at Hampton Court Palace in England (1522)

The Gothic style appeared in palaces in France, including the Papal Palace in Avignon and the Palais de la Cité in Paris, close to Notre-Dame de Paris, begun in 1119, which was the principal residence of the French Kings until 1417. Most of the Palais de la Cité is gone, but two of the original towers along the Seine, of the towers, the vaulted ceilings of the Hall of the Men-at-Arms (1302), (now in the Conciergerie; and the original chapel, Sainte-Chapelle, can still be seen.[53]

The largest civic building built in the Gothic style in France was the Palais des Papes (Palace of the Popes) constructed between 1252 and 1364, when the Popes fled the political chaos and wars enveloping Rome. Given the complicated political situation, it combined the functions of a church, a seat of government and a fortress.

In the 15th century, following the late Gothic or flamboyant period, elements of Gothic decoration borrowed from cathedrals began to appear in the town halls of northern France, in Flanders and in the Netherlands. The Hôtel de Ville of Compiègne has an imposing gothic bell tower, featuring a spire surrounded by smaller towers, and its windows are decorated with ornate accolades or ornamental arches. Similarly flamboyant town halls were found in Arras, Douai, and Saint-Quentin, Aisne, and in modern Belgium, in Brussels and Ghent and Bruges.[54]

Notable Gothic civil architecture in Spain includes the Silk Exchange in Valencia, Spain (1482–1548), a major marketplace, which features a main hall with twisting columns beneath its vaulted ceiling. Another Spanish Gothic landmark is the Palace of the Kings of Navarre in Olite (1269–1512), which combining the features of a palace and a fortress.

University Gothic

Gothic oriel window of the Karolinum of Charles University in Prague (around 1380)

Facade of the University of Salamanca in late Gothic Plateresque style (late 15th century)

Cloister of Collegium Maius in Krakow, Poland (late 15th century)

Chapel of King's College, Cambridge (1446–1544)

Tower and cloisters of Magdalen College, Oxford (1474–1480)

The first universities in Europe were closely associated with the Catholic church, and in the late 15th century they adapted variations of the Gothic style for their architecture. The Gothic style was adapted from English monasteries for use in the first colleges of Oxford University, including Magdalen College. It was also used at the University of Salamanca in Spain. The use of the late Gothic style at Oxford and Cambridge University inspired the picturesque Gothic architecture in U.S. colleges in the 19th and 20th century.

By the late Middle Ages university towns had grown in wealth and importance as well, and this was reflected in the buildings of some of Europe's ancient universities. Particularly remarkable examples still standing nowadays include the Collegio di Spagna in the University of Bologna, built during the 14th and 15th centuries; the Collegium Carolinum of the Charles University in Prague in Bohemia; the Escuelas mayores of the University of Salamanca in Spain; the chapel of King's College, Cambridge; or the Collegium Maius of the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland.

Military architecture

Donjon of the Château de Vincennes, begun 1337

Restored outer walls of the medieval city of Carcasonne (13th–14th century)

The Louvre in the time of Charles V of France (1338–1380) drawn by Eugene Viollet-le-Duc

Malbork Castle in Poland (13th century)

Alcazar of Segovia (12th–13th centuries)

Hohenzollern Castle (1454–1461) in Baden-Württemberg, southern Germany

In the 13th century, the design of the chateau fort, or castle, was modified, based on the Byzantine and Moslem castles the French knights had seen during the Crusades. The new kind of fortification was called Phillipienne, after Philippe Auguste, who had taken part in the Crusades. The new fortifications were more geometric, usually square, with a high main donjon or tower, in the center, which could be defended even if the walls of the castle were captured. The Donjon of the Chateau de Vincennes, begun by Philip VI of France, was a good example. It was 52 meters high, the tallest military tower in Europe.

In the Phillipienne castle other towers, usually round were placed at the corners and along the walls, close enough together to support each other. The walls had two levels of walkways on the inside, an upper parapet with openings (Crénaux) from which soldiers could watch or fire arrows on besiegers below; narrow openings (Merlons) through which they could be sheltered as they fired arrows; and floor openings (Mâchicoulis), from which they could drop rocks, burning oil or other objects on the besiegers. The upper walls also had protected protruding balconies, Échauguettes and Bretéches, from which soldiers could see what was happening at the corners or on the ground below. In addition, the towers and walls were pierced with narrow vertical slits, called Meurtriéres, through which archers could fire arrows. In later castles the slits took the form of crosses, so that archers could fire arbalètes, or crossbows, in different directions.[55]

Castles were surrounded by deep moat, spanned by a single drawbridge. The entrance was also protected by a grill of iron which could be opened and closed. The walls at the bottom were often sloping, and protected with earthen barriers. One good surviving example is the Château de Dourdan in the Seine-et-Marne department, near Nemours.[56]

After the end of the Hundred Years War (1337–1453), with improvements in artillery, the castles lost most of their military importance. They remained as symbols of the rank of their noble occupants; the narrowing openings in the walls were often widened into the windows of bedchambers and ceremonial halls. The tower of the Chateau of Vincennes became a royal residence.[57]

Decline

Beginning in the 16th century, as Renaissance architecture from Italy began to appear in France and other countries in Europe, the dominance of Gothic architecture began to wane. Nonetheless, new Gothic buildings, particularly churches, continued to be built; new Gothic churches built in Paris in this period included Saint-Merri (1520–1552); and Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois; The first signs of classicism in Paris churches, at St-Gervais-et-St-Protais, did not appear until 1540. The largest new church, Saint-Eustache (1532–1560), rivaled Notre-Dame in size, 105 meters long, 44 meters wide, and 35 meters high. As construction of this church continued, elements of Renaissance decoration, including the system of classical orders of columns, were added to the design, making it an early Gothic-Renaissance hybrid.[58]

The Gothic style began to be described as outdated, ugly and even barbaric. The term "Gothic" was first used as a pejorative description. Giorgio Vasari used the term "barbarous German style" in his 1550 Lives of the Artists to describe what is now considered the Gothic style.[3] In the introduction to the Lives he attributed various architectural features to "the Goths" whom he held responsible for destroying the ancient buildings after they conquered Rome, and erecting new ones in this style.[4] In the 17th century, Molière also mocked the Gothic style in the 1669 poem La Gloire: "...the insipid taste of Gothic ornamentation, these odious monstrosities of an ignorant age, produced by the torrents of barbarism..."[59] The dominant styles in Europe became in turn Italian Renaissance architecture, Baroque architecture, and the grand classicism of the Louis XIV style.

Nonetheless, Gothic architecture, usually churches or university buildings, continued to be built. Ireland was an island of Gothic architecture in the 17th and 18th centuries, with the construction of Derry Cathedral (completed 1633), Sligo Cathedral (c. 1730), and Down Cathedral (1790–1818) are other notable examples.[60] In the 17th and 18th century several important Gothic buildings were constructed at Oxford University and Cambridge University, including Tom Tower at Christ Church, Oxford, by Christopher Wren (1681–82) It also appeared, in a whimsical fashion, in Horace Walpole's Twickenham villa, Strawberry Hill (1749–1776) The two western towers of Westminster Abbey were constructed between 1722 and 1745 by Nicholas Hawksmoor, opening a new period of Gothic Revival.

Survival, rediscovery and revival

England

Great Hall at Lambeth Palace, London (1660–1663)

Tom Tower in Oxford, (1682)

Western façade of Westminster Abbey, London, completed in 1745

Elizabeth Tower (Big Ben) (completed in 1859) and the Houses of Parliament in London (1840–1876)

Chapel of Keble College, Oxford, completed 1876

St Pancras railway station, London

In England, partly in response to a philosophy propounded by the Oxford Movement and others associated with the emerging revival of 'high church' or Anglo-Catholic ideas during the second quarter of the 19th century, neo-Gothic began to become promoted by influential establishment figures as the preferred style for ecclesiastical, civic and institutional architecture. The appeal of this Gothic revival (which after 1837, in Britain, is sometimes termed Victorian Gothic), gradually widened to encompass "low church" as well as "high church" clients. This period of more universal appeal, spanning 1855–1885, is known in Britain as High Victorian Gothic.

The Houses of Parliament in London by Sir Charles Barry with interiors by a major exponent of the early Gothic Revival, Augustus Welby Pugin, is an example of the Gothic revival style from its earlier period in the second quarter of the 19th century. Examples from the High Victorian Gothic period include George Gilbert Scott's design for the Albert Memorial in London, and William Butterfield's chapel at Keble College, Oxford. From the second half of the 19th century onwards, it became more common in Britain for neo-Gothic to be used in the design of non-ecclesiastical and non-governmental buildings types. Gothic details even began to appear in working-class housing schemes subsidised by philanthropy, though given the expense, less frequently than in the design of upper and middle-class housing.

The middle of the 19th century was a period marked by the restoration, and in some cases modification, of ancient monuments and the construction of neo-Gothic edifices such as the nave of Cologne Cathedral and the Sainte-Clotilde of Paris as speculation of medieval architecture turned to technical consideration. London's Palace of Westminster, St. Pancras railway station, New York's Trinity Church and St. Patrick's Cathedral are also famous examples of Gothic Revival buildings.[61] Such style also reached the Far East in the period, for instance, the Anglican St. John's Cathedral which was located at the centre of Victoria City in Central, Hong Kong.

While some credit for this new ideation can reasonably be assigned to German and English writers, namely Johannes Vetter, Franz Mertens, and Robert Willis respectively, this emerging style's champion was Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, whose lead was taken by archaeologists, historians, and architects like Jules Quicherat, Auguste Choisy, and Marcel Aubert.[62] In the last years of the 19th century, a trend among study in art history emerged in Germany that a building, as defined by Henri Focillon was an interpretation of space.[63] When applied to Gothic cathedrals, historians and architects used to the dimensions of 17th and 18th Baroque or Neoclassical structures, were astounded by the height and extreme length of the cathedrals compared to its proportionally modest width. Goethe, in the preceding century, was mesmerised by the space within a Gothic church and succeeding historians like Georg Dehio, Walter Ueberwasser, Paul Frankl, and Maria Velte sought to rediscover the methodology used in their construction by making measurements and drawings of the buildings, and reading and making conjectures from documents and treaties pertaining to their construction.[17]

France

The Basilica of Sainte-Clotilde, Paris (1846–57)

Château de Pierrefonds (1857–1870), a combination of restoration and imagination

France had an abundance of original Gothic architecture, and therefore Gothic restoration largely replaced revival; few new buildings appeared in the Gothic style.

The French Revolution caused enormous damage to the Gothic architecture of France. Notre-Dame de Paris and other cathedrals and churches were closed and stripped of much of their decoration. In the 1830s, under the new King, Louis-Philippe, the historic and artistic value of Cathedrals and other Gothic monuments was recognized. Interest in the Gothic style was also stimulated by the huge success of the novel Notre Dame de Paris (known in English as The Hunchback of Notre Dame) by Victor Hugo, published in 1831. The writings of the romantic author François-René de Chateaubriand also played an important part; he praised the religious sentiments inspired by of the Gothic style, and declaring that the Gothic style was "the true architecture of our country," as important in the history of France as the forests of ancient Gaul.[64] A Commission of Historic Monuments was created in 1837, and major program of cataloging, protection and restoration of Gothic monuments was organized by the writer Prosper Merimée and conducted largely by the architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc.[64]

Viollet-le-Duc conducted the restoration of Notre Dame de Paris and many other churches, as well as the Gothic fortifications of Carcasonne and imaginatively finishing the castle of Château de Pierrefonds, which had been only a ruin.[65] He did not always limit himself to strict restoration of what had existed; in 1838 he designed he built a new Gothic west facade for the Parish church of Saint-Ouen in Rouen. The architects Franz Christian Gau and then Théodore Ballu built The Basilica of Sainte-Clotilde (1846–57), the first entirely neo-Gothic church in Paris.[66]

Germany and Russia

Gothic garden cottage of Leopold III, Duke of Anhalt-Dessau, in the Dessau-Wörlitz Garden Realm in Germany (1785–1783)

Neuschwanstein castle in Bavaria (1869–1876)

Tsaritsyno Palace palace near Moscow, built by Catherine the Great (1776–1796)

St. Alexander Nevsky Gothic Chapel (Peterhof), completed in 1834

German Gothic revival was born in 1785–86 in the Dessau-Wörlitz Garden Realm, an early landscape garden built by near Potsdam, in the garden of the country house of Leopold III, Duke of Anhalt-Dessau, designed by Friedrich Wilhelm von Erdmannsdorff. The Gothic House displayed his collection of medieval stained glass. It inspired other Gothic-style country houses near Berlin and Kassel. [67]

In Germany, the early 19th century Gothic revival had close ties to the movement of Romanticism. Beginning in 1814, the writer and historian Joseph Gorres launched a movement for the completion Cologne cathedral, which had been halted in 1473. The work was begun in 1842, and the two towers were completed in 1880, six hundred years after the cathedral was begun. Similar projects were undertaken for Ulm Minster, Heilsbronn Abbey and the Isartor gate in Munich. The Baroque decoration of these monuments was removed, and they were returned to at least an approximation, sometimes romanticized, of their original Gothic appearance. [67]

The most picturesque example of Gothic revival is Neuschwanstein Castle (1869–1876) in Bavaria built by Ludwig II of Bavaria. For inspiration, Ludwig visited other Gothic reconstruction projects, Warburg and Château de Pierrefonds, a castle which had been reconstructed by Eugene Viollet-le-Duc. The highly romantic Neuschwanstein Castle inspired, among other later buildings, the Sleeping Beauty Castle in Disneyland (1955).

Though Russia had no tradition of Gothic architecture, The Empress Catherine the Great chose the style in Tsaritsyno Palace, a large palace complex she constructed south of Moscow from 1776 until her death in 1796. Later, Czar Nicholas I of Russia commissioned the German romantic writer and painter Karl Friedrich Schinkel to design a Gothic chapel for his park at Peterhof Palace near St. Petersburg. It was completed in 1834.

Italy

Milan Cathedral in 1735, with its original facade

Milan Cathedral with new facade (1806–1813) and new crown on fronton (1888)

The Neo-Gothic Pedrocchi Café in Padua, Italy (1837)

The Gothic revival in Italy focused on the completion of earlier Cathedrals, which had been largely left to crumble. The most striking example was Milan Cathedral, which received a new facade in 1806–1813 which almost completely covered the original; it was designed by Giuseppe Zanoia and Carlo Amati. In 1888 it received a Gothic crown on the front facade by Giuseppe Brentano. The famous spires and pinnacles of the building date to the 19th century.[68]

A small but notable example of Gothic revival in Italy is the Pedrocchi Café in Padua, Italy (1837), by Giuseppe Jappelli. It borrowed the Venetian Gothic style plus the pinnacles of Milan Cathedral. It became famous as the meeting place of Italian patriots rebelling against Austrian rule in 1848.

Canada

Notre Dame Basilica in Montreal (1785–1795)

Buildings of Parliament of Canada, Ottawa (1859–1927) by Thomas Fuller

Library of Canadian Parliament in Ottawa (1859–1927) by Thomas Fuller

The Gothic Revival St. Michael's Cathedral in Toronto, by William Thomas (1845–1848)

One of the earliest and most highly decorated Gothic Revival churches in North America is the Notre-Dame Basilica in Montreal. Built in 1784–1795, on the site of a 17th-century church. The vaults are colored deep blue and decorated with golden stars, and the rest of the sanctuary is decorated in blues, azures, reds, purples, silver, and gold. The stained glass windows depict scenes from the religious history of Montreal.[69][70]

The English Gothic revival style was imported from England beginning in the 1830s, and was used primarily for Anglican and Catholic churches, and for university buildings. The best-known Gothic revival buildings in Canada are those Centre Bloc and the Victoria Tower of the Parliament of Canada on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, by Thomas Fuller (1859–1927).[71] The architect William Thomas constructed St. Michael's Cathedral in Toronto (1845–48), and several other Gothic revival churches in the Province of Ontario.

United States

Salt Lake Temple in Salt Lake City, Utah (1893)

St. Patrick's Cathedral (Manhattan) by James Renwick Jr. (dedicated 1910)

Gasson Hall on the campus of Boston College in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. (1908–1913)

Harkness Tower at Yale University by James Gamble Rogers (1917–1922)

Washington National Cathedral (Episcopal) (1907–1990)

Grace Cathedral (Episcopal) in San Francisco (1928–1964)

Oak Hill Cottage in Mansfield, Ohio, an example of Carpenter Gothic (1847)

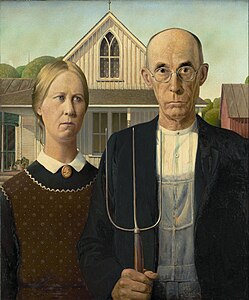

The painting American Gothic by Grant Wood took its name from the Carpenter Gothic house in the background.

Gothic crown of the Woolworth Building in New York City by Cass Gilbert (1910–1912). It was the world's tallest building when it was completed.

Detail of the top of the Woolworth Building, called a "Cathedral of Commerce".

Top of the Tribune Tower, Chicago (right) by John Mead Howells and Raymond Hood (1923–1925)

West entrance of the Tribune Tower, Chicago (1923–25)

The Gothic style was entirely contrary to the early Puritan architecture in the United States, which valued simplicity and a lack of ornament. It was also contrary to the Neoclassical style used for early U.S. government buildings. However, in the mid to late 19th century, large cathedrals and churches began to be built in the Gothic Revival style, modeled after European cathedrals. University buildings also adopted the style, using English colleges as a model. In the early 20th century, Gothic decorative elements appeared on the towers of the new skyscrapers, notably the Woolworth Building by Cass Gilbert in New York and the Chicago Tribune Building in Chicago, by John Mead Howells and Raymond Hood, symbolizing the role of these buildings as "cathedrals of commerce."[72][73]

Gothic architecture also inspired a popular style of residential architecture in the United States in the mid-19th century. It was known as Carpenter Gothic, and featured pointed lancet windows, a steep gable roof, and other simple Gothic elements, embellished with wooden ornament cut with a jigsaw or a scroll saw in Gothic designs. Sometimes the wooden trim was attached to a brick house. It became a popular style for wooden churches in rural communities. An example of Carpenter Gothic house, the American Gothic House, in Eldon, Iowa appears in the background of the celebrated painting American Gothic by Grant Wood, and gave the painting its name.[74][75]

Latin America, Asia and the Pacific

Perth Town Hall, Australia (1867–70)

Clock tower of Mumbai University, India (1870s)

Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus railway station (former Victoria Terminus), Mumbai, India (1878–1888)

Basilica of the Twenty-Six Holy Martyrs of Japan (Nagasaki) (1879)

Church of the Holy Sacrament, Guadalajara, Mexico (1897–1972)

Jakarta Cathedral, Indonesia (1901)