Peninsular War

| Peninsular War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Napoleonic Wars | |||||||

The Second of May 1808: The Charge of the Mamelukes by Francisco Goya, 1814 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

November 1808: April 1813: 172,000[3] | May 1808: 165,103[1] November 1808: 244,125[1] February 1809: 288,551[1] January 1810: 324,996[4] July 1811: 291,414[5] June 1812: 230,000[5] October 1812: 261,933[5] April 1813: 200,000[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 180,000–240,000 dead[7]

237,000 wounded[7] | ||||||

1,000,000+ military and civilian dead[7] | |||||||

The Peninsular War[c] (1807–1814) was a military conflict between Napoleon's empire and Bourbon Spain (with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland allied with the Kingdom of Portugal), for control of the Iberian Peninsula during the Napoleonic Wars. The war began when the French and Spanish armies invaded and occupied Portugal in 1807, and escalated in 1808 when France turned on Spain, previously its ally. The war on the peninsula lasted until the Sixth Coalition defeated Napoleon in 1814, and is regarded as one of the first wars of national liberation, significant for the emergence of large-scale guerrilla warfare.

The Peninsular War overlaps with what the Spanish-speaking world calls the Guerra de la Independencia Española (Spanish War of Independence), which began with the Dos de Mayo Uprising on 2 May 1808 and ended on 17 April 1814. The French occupation destroyed the Spanish administration, which fragmented into quarrelling provincial juntas. The episode remains as the bloodiest event in Spain's modern history, doubling in relative terms the Spanish Civil War.[9]

A reconstituted national government, the Cortes of Cádiz—in effect a government-in-exile—fortified itself in Cádiz in 1810, but could not raise effective armies because it was besieged by 70,000 French troops. British and Portuguese forces eventually secured Portugal, using it as a safe position from which to launch campaigns against the French army and provide whatever supplies they could get to the Spanish, while the Spanish armies and guerrillas tied down vast numbers of Napoleon's troops. These combined regular and irregular allied forces, by restricting French control of territory, prevented Napoleon's marshals from subduing the rebellious Spanish provinces, and the war continued through years of stalemate.[10]

The British Army, under then Lt. Gen. Sir Arthur Wellesley, later the 1st Duke of Wellington, guarded Portugal and campaigned against the French in Spain alongside the reformed Portuguese army. The demoralised Portuguese army was reorganised and refitted under the command of Gen. William Beresford,[11] who had been appointed commander-in-chief of the Portuguese forces by the exiled Portuguese royal family, and fought as part of the combined Anglo-Portuguese Army under Wellesley.

In 1812, when Napoleon set out with a massive army on what proved to be a disastrous French invasion of Russia, a combined allied army under Wellesley pushed into Spain, defeating the French at Salamanca and taking Madrid. In the following year Wellington scored a decisive victory over King Joseph Bonaparte's army in the Battle of Vitoria. Pursued by the armies of Britain, Spain and Portugal, Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult, no longer able to get sufficient support from a depleted France, led the exhausted and demoralized French forces in a fighting withdrawal across the Pyrenees during the winter of 1813–1814.

The years of fighting in Spain were a heavy burden on France's Grande Armée. While the French were victorious in battle, their communications and supplies were severely tested and their units were frequently isolated, harassed or overwhelmed by partisans fighting an intense guerrilla war of raids and ambushes. The Spanish armies were repeatedly beaten and driven to the peripheries, but they would regroup and relentlessly hound the French. This drain on French resources led Napoleon, who had unwittingly provoked a total war, to call the conflict the "Spanish Ulcer".[12][13]

War and revolution against Napoleon's occupation led to the Spanish Constitution of 1812, later a cornerstone of European liberalism.[14] The burden of war destroyed the social and economic fabric of Portugal and Spain, and ushered in an era of social turbulence, political instability and economic stagnation. Devastating civil wars between liberal and absolutist factions, led by officers trained in the Peninsular War, persisted in Iberia until 1850. The cumulative crises and disruptions of invasion, revolution and restoration led to the independence of most of Spain's American colonies and the independence of Brazil from Portugal.

Contents

1 Origins

1.1 Portuguese negotiations

1.2 Spanish situation

1.3 Invasion of Portugal

2 1808

2.1 Iberia in revolt

2.2 French counterattack

2.3 British intervention

2.4 Napoleon's invasion of Spain

2.5 Corunna Campaign, 1808–1809

3 1809

3.1 Spanish campaign, early 1809

3.1.1 Fall of Zaragoza

3.1.2 First Madrid Offensive

3.1.3 Liberation of Galicia

3.1.4 French advance in Catalonia

3.2 Second Portuguese campaign

3.3 Spanish campaign, late 1809

3.3.1 Talavera campaign

3.3.2 Second Madrid Offensive

4 1810

4.1 Joseph I's régime

4.2 Emergence of the guerrilla

4.3 Revolution under siege

4.4 Third Portuguese campaign

5 1811

5.1 Stalemate in the west

5.2 French conquest of Aragon

6 1812

6.1 Allied campaign in Spain

6.2 French autumn counterattack

7 1813

7.1 Defeat of King Joseph

7.2 End of the war in Spain

7.2.1 Campaign in the eastern Atlantic region

7.2.2 Campaign in the northern Mediterranean region

8 Invasion of France

8.1 Battles of the Nivelle and the Nive, November–December 1813

8.2 1814

9 Aftermath

10 Notes

11 References

12 Further reading

13 Other media

Origins

Portuguese negotiations

Princesa Line Infantry Regiment (left) and Catalonia Light Infantry Regiment (right)

The Treaties of Tilsit, negotiated during a meeting in July 1807 between Emperors Alexander I of Russia and Napoleon, concluded the War of the Fourth Coalition. With Prussia shattered, and the Russian Empire allied with the First French Empire, Napoleon expressed irritation that Portugal was open to trade with the United Kingdom.[15] Pretexts were plentiful; Portugal was Britain's oldest ally in Europe, Britain was finding new opportunities for trade with Portugal's colony in Brazil, the Royal Navy used Lisbon's port in its operations against France, and he wanted to deny the British the use of the Portuguese fleet. Furthermore, Prince John of Braganza, regent for his insane mother Queen Maria I, had declined to join the emperor's Continental System against British trade.[16]

Events moved rapidly. The Emperor sent orders on 19 July 1807 to his Foreign Minister, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, to order Portugal to declare war on Britain, close its ports to British ships, detain British subjects on a provisional basis and sequester their goods. After a few days, a large force started concentrating at Bayonne.[17] Meanwhile, the Portuguese government's resolve was stiffening, and shortly afterward Napoleon was once again told that Portugal would not go beyond its original agreements. Napoleon now had all the pretext that he needed, while his force, the First Corps of Observation of the Gironde with Divisional General Jean-Andoche Junot in command, was prepared to march on Lisbon. After he received the Portuguese answer, he ordered Junot's corps to cross the frontier into the Spanish Empire.[18]

While all this was going on, the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau had been signed between France and Spain. The document was drawn up by Napoleon's marshal of the palace Géraud Duroc and Eugenio Izquierdo, an agent for Manuel Godoy.[19] The treaty proposed to carve up Portugal into three entities. Porto and the northern part was to become the Kingdom of Northern Lusitania, under Charles II, Duke of Parma. The southern portion, as the Principality of the Algarves, would fall to Godoy. The rump of the country, centered on Lisbon, was to be administered by the French.[20] According to the Treaty of Fontainebleau, Junot's invasion force was to be supported by 25,500 Spanish troops.[21] On 12 October, Junot's corps began crossing the Bidasoa River into Spain at Irun.[18] Junot was selected because he had served as ambassador to Portugal in 1805. He was known as a good fighter and an active officer, although he never exercised independent command.[19]

Spanish situation

By 1800, the Kingdom of Spain was in a state of social unrest. Townsfolk and peasants all over the country, who had been forced to bury family members in new municipal cemeteries, took back their bodies at night and tried to restore them to their old resting-places. In Madrid, the growing afrancesado (Francophilia) of the court was opposed by the majos: shopkeepers, artisans, taverners and labourers who dressed in traditional style, and took pleasure in picking fights with petimetres, the young class who styled themselves with French fashion and manners.[22]

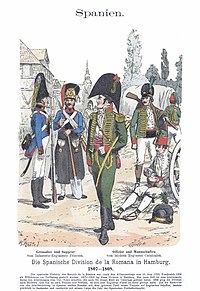

Spain was an ally of Napoleon's First French Empire; however, defeat at the Battle of Trafalgar in October 1805 had removed the reason for alliance with France. Godoy—who was a favourite of King Charles IV of Spain—began to seek some form of escape. At the start of the War of the Fourth Coalition, which pitted the Kingdom of Prussia against Napoleon, Godoy issued a proclamation that was obviously aimed at France, even though it did not specify an enemy. After Napoleon's decisive victory at the Battle of Jena–Auerstedt, Godoy quickly withdrew the proclamation. However, it was too late to avert the Emperor's suspicions. Napoleon planned from that moment to deal with his inconstant ally at some future time. In the meantime, the Emperor dragooned Godoy and Charles IV into providing a division of Spanish troops to serve in northern Europe.[23] The Division of the North spent the winter of 1807–1808 in Swedish Pomerania, Mecklenburg and towns of the old Hanseatic League. Spanish troops marched into Denmark in early 1808.[24]

Invasion of Portugal

The Portuguese royal family escapes to Brazil.

Concerned that Britain might intervene in Portugal or that the Portuguese might resist, Napoleon decided to speed up the invasion timetable, and instructed Junot to move west from Alcántara along the Tagus valley to Portugal, a distance of only 120 miles (193 km).[25] On 19 November 1807, Junot set out for Lisbon and occupied it on 30 November.[26]

The Prince Regent John escaped, loading his family, courtiers, state papers and treasure aboard the fleet. He was joined in flight by many nobles, merchants and others. With 15 warships and more than 20 transports, the fleet of refugees weighed anchor on 29 November and set sail for the colony of Brazil.[27] The flight had been so chaotic that 14 carts loaded with treasure were left behind on the docks.[28]

As one of Junot's first acts, the property of those who had fled to Brazil was sequestrated[29] and a 100-million-franc indemnity imposed.[30] The army formed into a Portuguese Legion, and went to northern Germany to perform garrison duty.[29] Junot did his best to calm the situation by trying to keep his troops under control. While the Portuguese civil authorities were generally subservient toward their occupiers, the common people were angry,[29] and the harsh taxes caused bitter resentment among the population. By January 1808, there were executions of persons who resisted the exactions of the French. The situation was dangerous, but it would need a trigger from outside to transform unrest into revolt.[30]

1808

Iberia in revolt

Second of May 1808: the defenders of Monteleón make their last stand

Francisco Goya painting, The Third of May 1808 (1814), depicting French soldiers executing civilians defending Madrid, would help make the uprising of May 2–3, 1808, a touchstone event of the Peninsular War. Notice how the painting emphasizes the man in white striking a Christ-like pose.[12]

In mid-March 1808, Godoy fell from power in the Mutiny of Aranjuez and Ferdinand VII came to the Spanish throne following the abdication of Charles IV. In its aftermath, attacks on godoyistas were frequent.[31] By the beginning of May 1808, rumours were spreading that the Junta de Gobierno—the council of regency left behind by Ferdinand—was being pressured into sending the last members of the royal family to Bayonne.[32]

On 2 May, the citizens of Madrid rebelled against the French occupation; the uprising was put down by Joachim Murat's elite Imperial Guard and Mamluk cavalry, which crashed into the city and trampled the rioters.[33] The next day, as immortalized by Francisco Goya in his painting The Third of May 1808, the French army shot hundreds of Madrid's citizens. Similar reprisals occurred in other cities and continued for days. Bloody, spontaneous fighting known as guerrilla (literally "little war") broke out in much of Spain against the French as well as the Ancien Régime's officials. Although the Spanish government, including the Council of Castile, had accepted Napoleon's decision to grant the Spanish crown to his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, the Spanish population rejected Napoleon's plans.[34] The first wave of uprisings were in Cartagena and Valencia on 23 May; Zaragoza and Murcia on 24 May; and the province of Asturias, which cast out its French governor on 25 May and declared war on Napoleon. Within weeks, all the Spanish provinces followed suit.[35] After hearing of the Spanish uprising, Portugal erupted in revolt in June. A French detachment under Louis Henri Loison crushed the rebels at Évora on 29 July and massacred the town's population.

The deteriorating strategic situation led France to increase its military commitments. By 1 June, over 65,000 troops were rushing into the country to control the crisis.[36] The main French army of 80,000 held a narrow strip of central Spain from Pamplona and San Sebastián in the north to Madrid and Toledo in the centre. The French in Madrid sheltered behind an additional 30,000 troops under Marshal Bon-Adrien Jeannot de Moncey. Jean-Andoche Junot's corps in Portugal was cut off by 300 miles (480 km) of hostile territory, but within days of the outbreak of revolt, French columns in Old Castile, New Castile, Aragon and Catalonia were searching for the insurgent forces.

French counterattack

Valencians prepare to resist the invaders in this 1884 painting by Joaquín Sorolla.

To defeat the insurgency, Pierre Dupont de l'Étang led 24,430 men south toward Seville and Cádiz; Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bessières moved into Aragon and Old Castile with 25,000 men, aiming to capture Santander and Zaragoza. Moncey marched toward Valencia with 29,350 men, and Guillaume Philibert Duhesme marshalled 12,710 troops in Catalonia and moved against Girona.[37]

At the two successive Combats of El Bruc outside Barcelona, Schwarz's 4,000 troops were defeated by local Catalan militia, the Miquelets (also known as sometents). Guillaume Philibert Duhesme's Franco-Italian division of almost 6000 troops failed to storm Girona and was forced to return to Barcelona.[38] 6000 French troops under Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes attacked Zaragoza and were beaten off by José de Palafox y Melci's militia.[39] Moncey's push to take Valencia ended in failure, with 1000 French recruits dying in an attempt to storm the city. After defeating Spanish counterattacks, Moncey retreated.[40] At the Battle of Medina de Rioseco on 14 July, Bessières defeated Cuesta and Old Castile returned to French control. Blake escaped, but the Spaniards lost 2,200 men and thirteen guns. French losses were minimal at 400 men.[41] Bessières's victory salvaged the French army's strategic position in northern Spain. Joseph entered Madrid on 20 July;[41] and on 25 July he was crowned King of Spain.[42] On 10 June, five French ships of the line anchored at Cádiz were seized by the Spanish.[43] Dupont was disturbed enough to curtail his march at Cordoba, and then on 16 June to fall back to Andújar.[44] Cowed by the mass hostility of the Andalusians, he broke off his offensive and was then defeated at Bailén, where he surrendered his entire Army Corps to Castaños.

The Spanish Army's triumph at Bailén was the French Empire's first land defeat. Painting by José Casado del Alisal

The catastrophe was total. With the loss of 24,000 troops, Napoleon's military machine in Spain collapsed. Stunned by the defeat, on 1 August Joseph evacuated the capital for Old Castile, while ordering Verdier to abandon the siege of Zaragoza and Bessières to retire from Leon; the entire French army sheltered behind the Ebro.[45] By this time, Girona had resisted a Second Siege. Europe welcomed this first check to the hitherto unbeatable Imperial armies—a Bonaparte had been chased from his throne; tales of Spanish heroism inspired Austria and showed the force of national resistance. Bailén set in motion the rise of the Fifth Coalition.[46]

British intervention

Portuguese and British troops fighting the French at Vimeiro.

Britain's involvement in the Peninsular War was the start of a prolonged campaign in Europe to increase British military power on land and liberate Spain from the French.[47] In August 1808, 15,000 British troops—including the King's German Legion—landed in Portugal under the command of Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Wellesley, who drove back Henri François Delaborde's 4,000-strong detachment at Roliça on 17 August and smashed Junot's main force of 14,000 men at Vimeiro. Wellesley was replaced at first by Sir Harry Burrard and then Sir Hew Dalrymple. Dalrymple granted Junot an unmolested evacuation from Portugal by the Royal Navy in the controversial Convention of Sintra in August. In early October 1808, following the scandal in Britain over the Convention of Sintra and the recall of the generals Dalrymple, Burrard, and Wellesley, Sir John Moore took command of the 30,000 man British force in Portugal.[48] In addition, Sir David Baird, in command of an expedition of reinforcements out of Falmouth consisting of 150 transports carrying between 12,000 and 13,000 men, convoyed by HMS Louie, HMS Amelia and HMS Champion, entered Corunna Harbour on 13 October.[49] Logistical and administrative problems prevented any immediate British offensive.[50]

Meanwhile, the British had made a substantial contribution to the Spanish cause by helping to evacuate some 9,000 men of La Romana's Division of the North from Denmark.[51] In August 1808, the British Baltic fleet helped transport the Spanish division, with the exception of three regiments that failed to escape, back to Spain by way of Gothenburg, Sweden. The division arrived in Santander in October 1808.[52]

Napoleon's invasion of Spain

La bataille de Somosierra by Louis-François, Baron Lejeune (1775–1848). Oil on canvas, 1810

After the surrender of a French army corps at Bailén and the loss of Portugal, Napoleon was convinced of the peril he faced in Spain. With his Armée d'Espagne of 278,670 men drawn up on the Ebro, facing 80,000 raw, disorganized Spanish troops,[53] Napoleon and his marshals carried out a massive double envelopment of the Spanish lines in November 1808.[54] Napoleon struck with overwhelming strength and the Spanish defense evaporated at Burgos, Tudela, Espinosa and Somosierra. Madrid surrendered itself on 1 December. Joseph Bonaparte was restored to his throne. The Junta was forced to abandon Madrid in November 1808, and resided in the Alcázar of Seville from 16 December 1808 until 23 January 1810.[55] In Catalonia, Laurent Gouvion Saint-Cyr's 17,000-strong VII Corps besieged and captured Roses from an Anglo-Spanish garrison, destroyed part of Juan Miguel de Vives y Feliu's Spanish army at Cardedeu near Barcelona on 16 December and routed the Spaniards under Conde de Caldagues and Theodor von Reding at Molins de Rei.

Corunna Campaign, 1808–1809

Death of Sir John Moore, 17 January 1809.

By November 1808, the British army led by Moore was advancing into Spain with orders to assist the Spanish armies' fight against Napoleon's forces.[56] Moore decided to attack Soult's scattered and isolated 16,000-man corps' at Carrión, opening his attack with a successful raid by Lieutenant-General Paget's cavalry on the French picquets at Sahagún on 21 December.[57][58]

Abandoning plans to immediately conquer Seville and Portugal, Napoleon rapidly amassed 80,000 troops and debouched from the Sierra de Guadarrama into the plains of Old Castile to encircle the British Army. Moore retreated for the safety of the British fleet at La Coruna and Soult failed to intercept him.[59][60] The rearguard of La Romana's retreating force was overrun at Mansilla on 30 December by Soult, who captured León the next day. Moore's retreat was marked by a breakdown of discipline in many regiments and punctuated by stubborn rearguard actions at Benavente and Cacabelos.[61] The British troops escaped to the sea after fending off a strong French attack at Corunna, in which Moore was killed. Some 26,000 troops reached Britain, with 7,000 men lost over the course of the expedition.[62] The French occupied the most populated region in Spain, including the important towns of Lugo and La Corunna.[63] The Spanish were shocked by the British retreat.[64] Napoleon returned to France on 19 January 1809 to prepare for war with Austria, giving the Spanish command back to his marshals.

1809

Spanish campaign, early 1809

Fall of Zaragoza

Saragossa: The assault on the Santa Engracia monastery. Oil on canvas, 1827

Zaragoza, already scarred from Lefebvre's bombardments that summer, was under a second siege that had commenced on 20 December. Lannes and Moncey committed two army corps of 45,000 men and considerable artillery firepower. Palafox's second defence brought the city enduring national and international fame.[65] The Spaniards fought with determination, endured disease and starvation, entrenching themselves in convents and burning their own homes. The garrison of 44,000 left 8,000 survivors—1,500 of them ill—[62] but the Grande Armée did not advance beyond the Ebro's shore. On 20 February 1809, the garrison capitulated, leaving behind burnt-out ruins filled with 64,000 corpses, of which 10,000 were French.[65][66]

First Madrid Offensive

The Junta took over direction of the Spanish war effort and established war taxes, organized an Army of La Mancha, signed a treaty of alliance with Britain on 14 January 1809 and issued a royal decree on 22 May to convene a Cortes. An attempt by the Spanish Army of the Center to recapture Madrid ended with the complete destruction of the Spanish forces at Uclés on 13 January by Victor's I Corps. The French lost 200 men while their Spanish opponents lost 6,887. King Joseph made a triumphant entry into Madrid after the battle. Sébastiani defeated Cartaojal's army at Ciudad Real on 27 March, inflicting 2,000 casualties and suffering negligible losses. Victor invaded southern Spain and routed Gregorio de la Cuesta's army at Medellín near Badajoz on 28 March.[67] Cuesta lost 10,000 men in a staggering defeat, while the French lost only 1,000.[68]

Liberation of Galicia

On 27 March, Spanish forces defeated the French at Vigo, recaptured most of the cities in the province of Pontevedra and forced the French to retreat to Santiago de Compostela. On 7 June, the French army of Marshal Michel Ney was defeated at Puente Sanpayo in Pontevedra by Spanish forces under the command of Colonel Pablo Morillo, and Ney and his forces retreated to Lugo on 9 June while being harassed by Spanish guerrillas. Ney's troops joined up with those of Soult and these forces withdrew for the last time from Galicia in July 1809.

French advance in Catalonia

In Catalonia, Saint-Cyr defeated Reding again at Valls on 25 February. Reding was killed and his army lost 3,000 men for French losses of 1,000. Girona was put under siege by Saint-Cyr on 6 May and the city finally fell on 12 December. Louis-Gabriel Suchet's III Corps was defeated at Alcañiz by Blake on 23 May, losing 2,000 men. Suchet retaliated at María on 15 June, crushing Blake's right wing and inflicting 5,000 casualties. Three days later, Blake lost 2,000 more men to Suchet at Belchite. Saint-Cyr was relieved of his command in September for deserting his troops.

Second Portuguese campaign

Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult at the First Battle of Porto by Joseph Beaume

After Corunna, Soult turned his attention to the invasion of Portugal. Discounting garrisons and the sick, Soult's II Corps had 20,000 men for the operation. He stormed the Spanish naval base at Ferrol on 26 January 1809, capturing eight ships of the line, three frigates, several thousand prisoners and 20,000 Brown Bess muskets, which were used to re-equip the French infantry.[69] In March 1809, Soult invaded Portugal through the northern corridor, with Francisco da Silveira's 12,000 Portuguese troops unraveling amid riot and disorder, and within two days of crossing the border Soult had taken the fortress of Chaves.[70] Swinging west, 16,000 of Soult's professional troops attacked and killed 4,000 of 25,000 unprepared and undisciplined Portuguese at Braga at the cost 200 Frenchmen. In the First Battle of Porto on 29 March, the Portuguese defenders panicked and lost between 6,000 and 20,000 men dead, wounded or captured and immense quantities of supplies. Suffering fewer than 500 casualties Soult had secured Portugal's second city with its valuable dockyards and arsenals intact.[71][72] Soult halted at Porto to refit his army before advancing on Lisbon.[67]

Wellesley returned to Portugal in April 1809 to command the British army, reinforced with Portuguese regiments trained by General Beresford. These new forces turned Soult out of Portugal at the Battle of Grijó (10–11 May) and the Second Battle of Porto (12 May), and the other northern cities were recaptured by General Silveira. Soult escaped without his heavy equipment by marching through the mountains to Orense.[67]

Spanish campaign, late 1809

Talavera campaign

Battle of Talavera by William Heath

With Portugal secured, Wellesley advanced into Spain to unite with Cuesta's forces. Victor's I Corps retreated before them from Talavera.[73] Cuesta's pursuing forces fell back after Victor's reinforced army, now commanded by Marshal Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, drove upon them. Two British divisions advanced to help the Spanish.[74] On 27 July at the Battle of Talavera, the French advanced in three columns and were repulsed several times, but at a heavy cost to the Anglo-Allied force, which lost 7,500 men for French losses of 7,400. Wellesley withdrew from Talavera on 4 August to avoid being cut off by Soult's converging army, which defeated a Spanish blocking force in an assault crossing at the River Tagus near Puente del Arzobispo. Lack of supplies and the threat of French reinforcement in the spring led Wellington to retreat into Portugal. A Spanish attempt to capture Madrid after Talavera failed at Almonacid, where Sébastiani's IV Corps inflicted 5,500 casualties on the Spanish, forcing them to retreat at the cost of 2,400 French losses.

Second Madrid Offensive

The Spanish Supreme Central and Governing Junta of the Kingdom was forced by popular pressure to set up the Cádiz Cortes in the summer of 1809. The Junta came up with what it hoped would be a war-winning strategy, a two-pronged offensive to recapture Madrid, involving over 100,000 troops in three armies under the Duke del Parque, Juan Carlos de Aréizaga and the Duke of Albuquerque.[75][76][77] Del Parque defeated Jean Gabriel Marchand's VI Corps at the Battle of Tamames on 18 October 1809.[78] and occupied Salamanca on 25 October.[79] Marchand was replaced by François Étienne de Kellermann, who brought up reinforcements in the form of his own men as well as General of Brigade Nicolas Godinot's force. Kellermann marched on Del Parque's position at Salamanca, who promptly abandoned it and retreated south. In the meantime, the guerrillas in the Province of León increased their activity. Kellermann left VI Corps holding Salamanca and returned to León to stamp out the uprising.[80]

Aréizaga's army was destroyed by Soult at the Battle of Ocaña on 19 November. The Spanish lost 19,000 men compared to French losses of 2,000. Albuquerque soon abandoned his efforts near Talavera. Del Parque moved on Salamanca again, hustling one of the VI Corps brigades out of Alba de Tormes and occupying Salamanca on 20 November.[81][82] Hoping to get between Kellermann and Madrid, Del Parque advanced towards Medina del Campo. Kellermann counterattacked and was repulsed at the Battle of Carpio on 23 November.[83] The next day, Del Parque received news of the Ocaña disaster and fled south, intending to shelter in the mountains of central Spain.[84][85] On the afternoon of 28 November, Kellermann attacked Del Parque at Alba de Tormes and routed him after inflicting losses of 3,000 men.[84] Del Parque's army fled into the mountains, its strength greatly reduced through combat and non-combat causes by mid-January.[86]

1810

Joseph I's régime

Joseph I of Spain

Joseph contented himself with working within the apparatus extant under the old regime, while placing responsibility for local government in many provinces in the hands of royal commissioners. After much preparation and debate, on 2 July 1809 Spain was divided into 38 new provinces, each headed by an Intendent appointed by King Joseph, and on 17 April 1810 these provinces were converted into French-style prefectures and sub-prefectures.

The French obtained a measure of acquiescence among the propertied classes. Francisco de Goya, who remained in Madrid throughout the French occupation, painted Joseph's picture and documented the war in a series of 82 prints called Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War). For many imperial officers, life could be comfortable.[87] Among the liberal, republican and radical segments of the Spanish and Portuguese populations there was much support for a potential French invasion. The term afrancesado ("turned French") was used to denote those who supported the Enlightenment, secular ideals, and the French Revolution.[88] Napoleon relied on support from these afrancesados both in the conduct of the war and administration of the country. Napoleon removed all feudal and clerical privileges but most Spanish liberals soon came to oppose the occupation because of the violence and brutality it brought.[88] Marxians wrote that there was a positive identification on the part of the people with the Napoleonic revolution, but this is probably impossible to substantiate by the reasons for collaboration being practical rather than ideological.[89]

Emergence of the guerrilla

Juan Martín Díez, El Empecinado, a key guerrilla leader

The Peninsular War is regarded as one of the first people's wars, significant for the emergence of large-scale guerrilla warfare. It is from this conflict that the English language borrowed the word.[90] The guerrillas troubled the French troops, but they frightened their own countrymen with forced conscription and looting.[citation needed] Many of the partisans were either fleeing the law or trying to get rich. Later in the war the authorities tried to make the guerrillas reliable, and many of them formed regular army units such as Espoz y Mina's "Cazadores de Navarra". The French believed that enlightened absolutism had made less progress in Spain and Portugal than elsewhere, and that resistance was the product of a century's worth of what the French perceived as backwardness in knowledge and social habits, Catholic obscurantism, superstition and counter-revolution.[91]

The guerrilla style of fighting was the Spanish military's single most effective tactic. Most organized attempts by regular Spanish forces to take on the French ended in defeat. Once a battle was lost and the soldiers reverted to their guerrilla roles, they tied down large numbers of French troops over a wide area with a much lower expenditure of men, energy, and supplies[citation needed] and facilitated the conventional victories of Wellington and his Anglo-Portuguese army and the subsequent liberation of Portugal and Spain.[92] Mass resistance by the people of Spain inspired the war efforts of Austria, Russia and Prussia against Napoleon.[93]

Hatred of the French and devotion to God, King and Fatherland were not the only reason to join the Partisans.[94] The French imposed restrictions on movement and on many traditional aspects of street life, so opportunities to find alternative sources of income were limited—industry was at a standstill and many señores were unable to pay their existing retainers and domestic servants, and could not take on new staff. Hunger and despair reigned on all sides.[95] Because the military record was so dismal, many Spanish politicians and publicists exaggerated the activities of the guerrillas.[96]

Revolution under siege

Map of Cádiz in 1813

The French invaded Andalusia on 19 January 1810. 60,000 French troops—the corps of Victor, Mortier and Sebastiani together with other formations—advanced southwards to assault the Spanish positions. Overwhelmed at every point, Aréizaga's men fled eastwards and southwards, leaving town after town to fall into the hands of the enemy. The result was revolution. On 23 January the Junta Central decided to flee to the safety of Cádiz.[97] It then dissolved itself on 29 January 1810 and set up a five-person Regency Council of Spain and the Indies, charged with convening the Cortes.[55] Soult cleared all of southern Spain except Cádiz, which he left Victor to blockade.[67] The system of juntas was replaced by a regency and the Cádiz Cortes, which established a permanent government under the Constitution of 1812.

Cadiz was heavily fortified, while the harbour was full of British and Spanish warships. Alburquerque's army and the Voluntarios Distinguidos had been reinforced by 3,000 soldiers who had fled Seville, and a strong Anglo-Portuguese brigade commanded by General William Stewart. Shaken by their experiences, the Spaniards had abandoned their earlier scruples about a British garrison.[98] Victor's French troops camped at the shoreline and tried to bombard the city into surrender. Thanks to British naval supremacy, a naval blockade of the city was impossible. The French bombardment was ineffectual and the confidence of the gaditanos grew and persuaded them that they were heroes. With food abundant and falling in price, the bombardment was hopeless despite both hurricane and epidemic—a storm destroyed many ships in the spring of 1810 and the city was ravaged by yellow fever.[99]

Once Cádiz was secured, attention turned to the political situation. The Junta Central announced that the cortes would open on 1 March 1810. Suffrage was to be extended to all male householders over 25. After public voting, representatives from district-level assemblies would choose deputies to send to the provincial meetings that would be the bodies from which the members of the cortes would emerge.[100] From 1 February 1810, the implementation of these decrees had been in the hands of the new regency council selected by the Junta Central.[101] The viceroyalties and independent captaincies general of the overseas territories would each send one representative. This scheme was resented in America for providing unequal representation to the overseas territories. Unrest erupted in Quito and Charcas, which saw themselves as the capitals of kingdoms and resented being subsumed in the larger "kingdom" of Peru. The revolts were suppressed (See Luz de América and Bolivian War of Independence). Throughout early 1809 the governments of the capitals of the viceroyalties and captaincies general elected representatives to the Junta, but none arrived in time to serve on it.

Third Portuguese campaign

The Battle of Chiclana, 5th March 1811 (1824) captures the fight between British redcoats and the French troops for Barrosa Ridge.[12]

Convinced by intelligence that a new French assault on Portugal was imminent, Wellington created a powerful defensive position near Lisbon, to which he could fall back if necessary.[102][103] To protect the city, he ordered the construction of the Lines of Torres Vedras—three strong lines of mutually supporting forts, blockhouses, redoubts, and ravelins with fortified artillery positions—under the supervision of Sir Richard Fletcher. The various parts of the lines communicated with each other by semaphore, allowing immediate response to any threat. The work began in the autumn of 1809 and the main defences were finished just in time one year later. To further hamper the enemy, the areas in front of the lines were subjected to a scorched earth policy: they were denuded of food, forage and shelter. 200,000 inhabitants of neighbouring districts were relocated inside the lines. Wellington exploited the facts that the French could conquer Portugal only by conquering Lisbon, and that they could in practice reach Lisbon only from the north. Until these changes occurred the Portuguese administration was free to resist British influence, Beresford's position being rendered tolerable by the firm support of the Minister of War, Miguel de Pereira Forjaz.[104]

As a prelude to invasion, Ney took the Spanish fortified town of Ciudad Rodrigo after a siege lasting from 26 April to 9 July 1810. The French re-invaded Portugal with an army of around 65,000, led by Marshal Masséna, and forced Wellington back through Almeida to Busaco.[67] At the Battle of the Côa the French drove back Robert Crauford's Light Division after which Masséna moved to attack the held British position on the heights of Bussaco—a 10-mile (16 km)-long ridge—resulting in the Battle of Buçaco on 27 September. Suffering heavy casualties, the French failed to dislodge the Anglo-Portuguese army. Masséna outmaneuvered Wellington after the battle, who steadily fell back to the prepared positions in the Lines.[105] Wellington manned the fortifications with "secondary troops"—25,000 Portuguese militia, 8,000 Spaniards and 2,500 British marines and artillerymen—keeping his main field army of British and Portuguese regulars dispersed to meet a French assault on any point of the Lines.[106]

Masséna's Army of Portugal concentrated around Sobral in preparation to attack. After a fierce skirmish on 14 October in which the strength of the Lines became apparent, the French dug themselves in rather than launch a full-scale assault and Masséna's men began to suffer from the acute shortages in the region.[107] In late October, after holding his starving army before Lisbon for a month, Masséna fell back to a position between Santarém and Rio Maior.[108]

1811

Stalemate in the west

Spanish commander Joaquín Blake y Joyes

During 1811, Victor's force was diminished because of requests for reinforcement from Soult to aid his siege of Badajoz.[109] This brought the French numbers down to between 20,000 and 15,000 and encouraged the defenders of Cádiz to attempt a breakout,[109] in conjunction with the arrival of an Anglo-Spanish relief army of around 12,000 infantry and 800 cavalry under the overall command of Spanish General Manuel La Peña, with the British contingent being led by Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Graham.[110] Marching towards Cádiz on 28 February, this force defeated two French divisions under Victor at Barrosa. The Allies failed to exploit their success and Victor soon renewed the blockade.[111] From January through March 1811, Soult with 20,000 men besieged and captured the fortress towns of Badajoz and Olivenza in Extremadura, capturing 16,000 prisoners, before returning to Andalusia with most of his army. Soult was relieved at the operation's speedy conclusion, for intelligence received on 8 March told him that Francisco Ballesteros' Spanish army was menacing Seville, that Victor had been defeated at Barrosa and Masséna had retreated from Portugal. Soult redeployed his forces to deal with these threats.[112]

In March 1811, with supplies exhausted, Masséna retreated from Portugal to Salamanca. Wellington went over to the offensive later that month. An Anglo-Portuguese army led by the British Marshal William Beresford and a Spanish army led by the Spanish generals Joaquín Blake and Francisco Castaños, attempted to retake Badajoz by laying siege to the French garrison Soult had left behind. Soult regathered his army and marched to relieve the siege. Beresford lifted the siege and his army intercepted the marching French. At the Battle of Albuera, Soult outmaneuvered Beresford but could not win the battle. He retired his army to Seville.[113]

In April, Wellington besieged Almeida. Massena advanced to its relief, attacking Wellington at Fuentes de Oñoro (3–5 May). Both sides claimed victory but the British maintained the blockade and the French retired without being attacked. After this battle, the Almeida garrison escaped through the British lines in a night march.[67] Masséna was forced to withdraw, having lost a total of 25,000 men in Portugal, and was replaced by Auguste Marmont. Wellington joined Beresford and renewed the siege of Badajoz. Marmont joined Soult with strong reinforcements and Wellington retired.[67]

Wellington soon appeared before Ciudad Rodrigo. In September, Marmont repelled him and re-provisioned the fortress.[67] Sorties continued to be made out of Cádiz from April to August 1811,[114] and British naval gunboats destroyed French positions at St. Mary's.[115] An attempt by Victor to crush the small Anglo-Spanish garrison at Tarifa over the winter of 1811–1812 was frustrated by torrential rains and an obstinate defence, marking an end to French operations against the city's outer works.

French conquest of Aragon

After a two-week siege, the French Army of Aragon under its commander, General Suchet, captured the town of Tortosa from the Spanish in Catalonia on 2 January 1811. MacDonald's VII Corps was defeated in a vanguard skirmish at El Pla.

The Spanish commander Francisco Rovira captured in a coup-de-main the key fortress of Figueres with the help of 2,000 men on 10 April. The French Army of Catalonia under MacDonald blockaded the city to starve the defenders into surrender. With the help of a relief operation on 3 May, the fortress held out until 17 August, when lack of food prompted a surrender after a last-ditch breakout attempt failed.[116]

On 5 May, Suchet besieged the vital city of Tarragona, which functioned as a port, a fortress, and a resource base that sustained the Spanish field forces in Catalonia. Suchet was given a third of the Army of Catalonia and the city fell to a surprise attack on 29 June.[117] Suchet's troops massacred 2,000 civilians. Napoleon rewarded Suchet with a Marshal's baton. On 25 July, Suchet drove the Spanish out of their positions on the Montserrat mountain range. In October, the Spanish launched a counterattack that recaptured Montserrat and took 1,000 prisoners from scattered French garrisons in the area. In September, Suchet launched an invasion of the province of Valencia. He besieged the castle of Sagunto and defeated Blake's relief attempt. The Spanish defenders capitulated on 25 October. Suchet trapped Blake's entire army of 28,044 men in the city of Valencia on 26 December and forced it to surrender on 9 January 1812 after a brief siege. Blake lost 20,281 men dead or captured. Suchet advanced south, capturing the port town of Dénia. The redeployment of a substantial part of his troops for the invasion of Russia ground Suchet's operations to a halt. The victorious Marshal had established a secure base in Aragon and was ennobled by Napoleon as the Duke of Albufera, after a lagoon south of Valencia.

The war now fell into a temporary lull, with the superior French unable to find an advantage and coming under increasing pressure from Spanish guerrillas. The French had over 350,000 soldiers in L'Armée de l'Espagne, but over 200,000 were deployed to protect the French lines of supply, rather than as substantial fighting units.

1812

Allied campaign in Spain

British infantry attempt to scale the walls of Badajoz, 1812

The Battle of Salamanca

The Proclamation of the Constitution of 1812 by Salvador Viniegra

Wellington renewed the allied advance into Spain in early 1812, besieging and capturing the border fortress town of Ciudad Rodrigo by assault on 19 January and opening up the northern invasion corridor from Portugal into Spain. This also allowed Wellington to proceed to move to capture the southern fortress town of Badajoz, which would prove to be one of the bloodiest siege assaults of the Napoleonic Wars.[118] The town was stormed on 6 April, after a constant artillery barrage had breached the curtain wall in three places. Tenaciously defended, the final assault and the earlier skirmishes left the allies with some 4,800 casualties. These losses appalled Wellington who said of his troops in a letter, "I greatly hope that I shall never again be the instrument of putting them to such a test as that to which they were put last night."[119] The victorious troops massacred about 4,000 Spanish civilians.[120]

The allied army subsequently took Salamanca on 17 June, just as Marshal Marmont approached. The two forces met on 22 July, after weeks of maneuver, when Wellington soundly defeated the French at the Battle of Salamanca, during which Marmont was wounded. The battle established Wellington as an offensive general and it was said that he "defeated an army of 40,000 men in 40 minutes."[121] The Battle of Salamanca was a damaging defeat for the French in Spain, and while they regrouped, Anglo-Portuguese forces moved on Madrid, which surrendered on 14 August. 20,000 muskets, 180 cannon and two French Imperial Eagles were captured.[122]

French autumn counterattack

After the allied victory at Salamanca on 22 July 1812, King Joseph Bonaparte abandoned Madrid on 11 August.[123] Because Suchet had a secure base at Valencia, Joseph and Marshal Jean-Baptiste Jourdan retreated there. Soult, realising he would soon be cut off from his supplies, ordered a retreat from Cádiz set for 24 August; the French were forced to end the two-and-a-half-year-long siege.[12] After a long artillery barrage, the French placed together the muzzles of over 600 cannons to render them unusable to the Spanish and British. Although the cannons were useless, the Allied forces captured 30 gunboats and a large quantity of stores.[124] The French were forced to abandon Andalusia for fear of being cut off by the allied armies.[125] Marshals Suchet and Soult joined Joseph and Jourdan at Valencia. Spanish armies defeated the French garrisons at Astorga and Guadalajara.

As the French regrouped, the allies advanced towards Burgos. Wellington besieged Burgos between 19 September and 21 October, but failed to capture it. Together, Joseph and the three marshals planned to recapture Madrid and drive Wellington from central Spain. The French counteroffensive caused Wellington to lift the Siege of Burgos and retreat to Portugal in the autumn of 1812,[126] pursued by the French and losing several thousand men.[67] Napier wrote that about 1,000 allied troops were killed, wounded and missing in action, and that Hill lost 400 between the Tagus and the Tormes, and another 100 in the defence of Alba de Tormes. 300 were killed and wounded at the Huebra where many stragglers died in woodland, and 3,520 allied prisoners were taken to Salamanca up to 20 November. Napier estimated that the double retreat cost the allies around 9,000, including the loss in the siege, and said French writers said 10,000 were taken between the Tormes and the Agueda. But Joseph's dispatches said the whole loss was 12,000, including the garrison of Chinchilla, whereas English authors mostly reduced the British loss to hundreds.[127] As a consequence of the Salamanca campaign, the French were forced to evacuate the provinces of Andalusia and Asturias. For Napoleon, losing in Spain in 1812 or 1813 would have meant little if a decisive victory had occurred in Germany or Russia.[67]

1813

Defeat of King Joseph

By the end of 1812, the Grande Armée that had invaded the Russian Empire had ceased to exist. Unable to resist the oncoming Russians, the French had to evacuate East Prussia and the Grand Duchy of Warsaw. With both the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia joining his opponents, Napoleon withdrew more troops from Spain,[128] including some foreign units and three battalions of sailors sent to assist with the Siege of Cádiz. 20,000 men were withdrawn; the numbers were not overwhelming, but the occupying forces were left in a difficult position. In much of the area under French control—the Basque provinces, Navarre, Aragon, Old Castile, La Mancha, the Levante, and parts of Catalonia and León—their presence was a few scattered garrisons. Trying to hold a front line in an arc from Bilbao to Valencia, they were still vulnerable to assault, and had abandoned hopes of victory. According to Esdaile, the best policy would have been to have fallen back to the Ebro, but the political situation in 1813 made this impossible; Napoleon wanted to avoid being seen as weak in the face of German princes watching the advancing Russians and wondering whether they should change sides.[129] French prestige suffered another blow when on 17 March el rey intruso (the Intrusive King, a nickname many Spanish had for King Joseph) left Madrid in the company of another vast caravan of refugees.[129]

In 1813, Wellington marched 121,000 troops (53,749 British, 39,608 Spanish, and 27,569 Portuguese)[130] from northern Portugal across the mountains of northern Spain and the Esla River, skirting Jourdan's army of 68,000 strung out between the Douro and the Tagus. Wellington shortened his communications by shifting his base of operations to the northern Spanish coast and the Anglo-Portuguese forces swept northwards in late May and seized Burgos, outflanking the French army and forcing Joseph Bonaparte into the Zadorra valley.

Map of the Battle of Vitoria

At the Battle of Vitoria on 21 June, Joseph's 65,000-man army were decisively defeated by Wellington's army of 57,000 British, 16,000 Portuguese and 8,000 Spanish.[130] Wellington split his army into four attacking "columns" and attacked the French defensive position from south, west and north while the last column cut down across the French rear. The French were forced back from their prepared positions, and despite attempts to reform and hold were driven into a rout. This led to the abandonment of all of the French artillery as well as King Joseph's extensive baggage train and personal belongings. The latter led to many Anglo-Allied soldiers halting the pursuit to loot the wagons; as a result they could not complete the pursuit and this, along with the French managing to hold the east road out of Vitoria towards Salvatierra, allowed the French to partially recover. The Allies chased the retreating French, reaching the Pyrenees in early July, and began operations against San Sebastian and Pamplona. On 11 July Soult was given command of all French troops in Spain and in consequence Wellington decided to halt his army to regroup at the Pyrenees.

The war was not over. Although Bonapartist Spain had effectively collapsed, most of France's troops had escaped and fresh troops were soon gathering beyond the Pyrenees. By themselves, such forces were unlikely to score more than a few local victories, but French troop losses elsewhere in Europe could not be taken for granted. Napoleon might yet inflict defeats on Austria, Russia and Prussia, and with the divisions between the allies there was no guarantee that one power would not make a separate peace. It was a major victory and gave Britain more credibility on the continent, but the thought of Napoleon descending on the Pyrenees with the grande armée was not regarded with equanimity.[131]

End of the war in Spain

Campaign in the eastern Atlantic region

In August 1813, British headquarters still had misgivings about the eastern powers. Austria had now joined the Allies, but the Allied armies had suffered a significant defeat at the Battle of Dresden. They had recovered somewhat, but the situation was still precarious. Wellington's brother-in-law Edward Pakenham wrote, "I should think that much must depend upon proceedings in the north: I begin to apprehend ... that Boney may avail himself of the jealousy of the Allies to the material injury of the cause."[132] But the defeat or defection of Austria, Russia and Prussia was not the only danger. It was also uncertain that Wellington could continue to count on Spanish support.[133]

The summer of 1813 in the Basque provinces and Navarre was a wet one, and with the army drenched by incessant rain and the decision to strip the men of their greatcoats was looking unwise. Sickness was widespread—at one point a third of Wellington's British troops were hors de combat—and fears about the army's discipline and general reliability grew. By 9 July, Wellington reported that 12,500 men were absent without leave, while plundering was rife. Major General Sir Frederick Robinson wrote, "We paint the conduct of the French in this country in very ... harsh colours, but be assured we injure the people much more than they do ... Wherever we move devastation marks our steps".[134] With the army established on the borders of France, desertion had become a problem. The Chasseurs Britanniques—recruited mainly from French deserters—lost 150 men in a single night. Wellington wrote, "The desertion is terrible, and is unaccountable among the British troops. I am not astonished that the foreigners should go ... but, unless they entice away the British soldiers, there is no accounting for their going away in such numbers as they do."[135]

Spain's "ragged and ill-fed soldiers" were also suffering with the onset of winter, the fear that they would likely "fall on the populace with the utmost savagery"[136] in revenge attacks and looting was a growing concern to Wellington as the Allied forces pushed to the French border.

Battle of the Pyrenees, 25 July 1813

Marshal Soult began a counter-offensive (the Battle of the Pyrenees) and defeated the Allies at the Battle of Maya and the Battle of Roncesvalles (25 July). Pushing on into Spain, by 27 July the Roncesvalles wing of Soult's army was within ten miles of Pamplona but found its way blocked by a substantial allied force posted on a high ridge in between the villages of Sorauren and Zabaldica, lost momentum, and was repulsed by the Allies at the Battle of Sorauren (28 and 30 July)[137] Reille's right wing suffered further losses at Yanzi (1 August); and the Echallar and Ivantelly (2 August) during its retreat into France.[138][139][140] Total losses during this counter-offensive being about 7,000 for the Allies and 10,000 for the French.[138]

With 18,000 men, Wellington captured the French-garrisoned city of San Sebastián under Brigadier-General Louis Emmanuel Rey after two sieges that lasted from 7 July to 25 July (While Wellington departed with sufficient forces to deal with Marshal Soult's counter-offensive, he left General Graham in command of sufficient forces to prevent sorties from the city and any relief getting in); and from 22 August to 31 August 1813. The British incurred heavy losses during assaults. The city in turn was sacked and burnt to the ground by the Anglo-Portuguese: see Siege of San Sebastián. Meanwhile, the French garrison retreated into the Citadel, which after a heavy bombardment their governor surrendered on 8 September, with the garrison marching out the next day with full military honours.[141] Upon the day that San Sebastián fell Soult attempted to relieve it, but in the battles of Vera and San Marcial was repulsed[138] by the Spanish Army of Galicia under General Manuel Freire.[142] The Citadel surrendered on 9 September, the losses in the entire siege having been about—Allies 4,000, French 2,000. Wellington next determined to throw his left across the river Bidassoa to strengthen his own position, and secure the port of Fuenterrabia.[138]

The Battle of the Bidassoa, 1813

At daylight on 7 October 1813 Wellington crossed the Bidassoa in seven columns, attacked the entire French position, which stretched in two heavily entrenched lines from north of the Irun-Bayonne road, along mountain spurs to the Great Rhune 2,800 feet (850 m) high.[143] The decisive movement was a passage in strength near Fuenterrabia to the astonishment of the enemy, who in view of the width of the river and the shifting sands, had thought the crossing impossible at that point. The French right was then rolled back, and Soult was unable to reinforce his right in time to retrieve the day. His works fell in succession after hard fighting, and he withdrew towards the river Nivelle.[144] The losses were about—Allies, 800; French, 1,600.[145] The passage of the Bidassoa "was a general's not a soldier's battle".[146][144]

On 31 October Pamplona surrendered, and Wellington was now anxious to drive Suchet from Catalonia before invading France. The British government, however, in the interests of the continental powers, urged an immediate advance over the northern Pyrennes into south-eastern France.[138] Napoleon had just suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Leipzig on 19 October and was in retreat,[citation needed] so Wellington left the clearance of Catalonia to others.[138]

Campaign in the northern Mediterranean region

Battle of Castalla

In the northern Mediterranean region of Spain (Catalonia) Suchet had defeated Elio's Murcians at Yecla and Villena (11 April 1813), but was subsequently routed by Lieutenant General Sir John Murray[147] at the battle of Castalla (13 April), who then besieged Tarragona. The siege was abandoned after a time, but was later on renewed by Lieutenant General Lord William Bentinck. Suchet, after the Battle of Vitoria, evacuated Tarragona (17 August) but defeated Bentinck in the battle of Ordal (13 September).[144]

The military historian Sir Charles Oman wrote that because of "[Napoleon's] absurdly optimistic reliance on" the Treaty of Valençay (11 December 1813),[148] during the last month of 1813 and the early months of 1814 Suchet was ordered by the French War office to relinquish command of many of his infantry and cavalry regiments for use in the campaign in north-east France where Napoleon was greatly outnumbered. This reduced Suchet's French Catalonian army from 87,000 to 60,000 of whom 10,000 were on garrison duty. By the end of January through redeployment and wastage (through disease and desertion) the number had fallen to 52,000 of whom only 28,000 were available for field operations the others were either on garrison duties or guarding the lines of communication back into France.[149]

Suchet though that the armies under the command of the Spanish General Copons and the British General Clinton amounted to 70,000 men (in fact they only had about as many as he did), so Suchet remained on the defensive.[150]

On the 10 January Suchet received orders from the French War Ministry that he to withdraw his field force to the foothills of the Pyrenees and to make a phased withdraw from the outlying garrisons. On ratification of the Treaty of Valençay move his force to the French city of Lyons.[151] On the 14 January he received further orders that because the situation was so grave on the eastern front he was to immediately send further forces to the east, even though ratification of the Treaty of Valençay had not been received. This would reduce the size of Suchet's field army to 18,000 men.[152]

The Allies heard that Suchet was hemorrhaging men and mistakenly thought that his army was smaller than it was, so on the 16 January they attacked. Suchet had not yet started the process of sending more men back to France and was able to stop the Sicilians (and a small contingent of British artillery in support) at the Battle of Molins de Rey because he still had a local preponderance of men. The allies suffered 68 casualties the French 30 killed and about 150 wounded.[151]

After Suchet sent many men to Lyons, he left an isolated garrison in Barcelona and concentrated his forces on the town of Gerona calling in flying columns and evacuating some minor outposts. However his field army was now down to 15,000 cavalry and infantry (and excluding the garrisons in northern Catalonia).[153]

The last actions in this theatre happened at the siege of Barcelona on 23 February the French sallied out of Barcelona to test the besieges lines, as they thought (wrongly) that the Anglo-Sicilian forces had departed. They failed to break through the lines and forces under the command of the Spanish General Pedro Sarsfield stopped them. The French General Pierre-Joseph Habert tried another sortie on 16 April (several days after Napoleon had abdicated) and the French were again stopped with about 300 of them killed.[154] Habert eventually surrendered on 25 April.[155]

On 1 March Suchet received orders to send 10,000 more men to Lyons. On 7 March Beurmann's division of 9,661 men left for Lyons. With the exception of Figueras Suchet abandoned all the remaining fortresses in Catalonia that the French garrisoned (and that were not were not closely besieged by Allied forces), and in doing so was able to create a new field force of about 14,000 men which were concentrated in front of Figueras in early April.[156][d]

In the meantime the Allies under estimating the size of Suchet's force and believing that 3,000 more men had left for Lyon and the Suchet with the remnant of his army was crossing the Pyrenees to join Soult in the Atlantic theatre start to redeploy their forces. The best of the British forces in Catalonia were ordered to join Wellinton's army on the river Garonne in France.[e] They left to do so on 31 March leaving the Spanish to mop up the remaining French garrisons in Catalonia.[154]

In fact Suchet remained in Figueras with his army until after the amnesty signed by Wellington and Soult. He spent his time arguing with Soult that he had only 4,000 troops available to March (although his army numbered around 14,000) and that they could not march with artillery so he could not assist Soult in his battles with Wellington.[157] The Military historian Sir Charles Oman puts this refusal to help Soult down to Suchet's personal animosity rather than strong strategic reasons.[158]

Invasion of France

Battles of the Nivelle and the Nive, November–December 1813

The Battle of Nivelle

On the night of 9 November 1813 Wellington brought up his right from the Pyrenean passes to the northward of Maya and towards the Nivelle. Marshal Soult's army (about 79,000), in three entrenched lines, stretched from the sea in front of Saint-Jean-de-Luz along commanding ground to Amotz and thence, behind the river, to Mont Mondarrain near the Nive.[144] Wellington on 10 November 1813 attacked and drove the French to Bayonne. The allied loss during the Battle of Nivelle was about 2,700; that of the French 4,000, 51 guns, and all their magazines. The next day Wellington closed in upon Bayonne from the sea to the left bank of the Nive.[144]

After this there was a period of comparative inaction, though during it the French were driven from the bridges at Urdains[f] and Cambo-les-Bains.[g] The weather had become bad, and the Nive unfordable; but there were additional and serious causes of delay. The Portuguese and Spanish authorities were neglecting the payment and supply of their troops. Wellington had also difficulties of a similar kind with his own government, and also the Spanish soldiers, in revenge for many French outrages, had become guilty of grave excesses in France, so that Wellington took the extreme step of sending 25,000 of them back to Spain and resigning the command of their army (though his resignation was subsequently withdrawn). So great was the tension at this crisis that a rupture with Spain seemed possible, but this did not happen.[144][h]

Battle of St Jean de Luz, 10 December 1813 by Thomas Sutherland.

Wellington occupied the right as well as the left bank of the Nive on 9 December 1813 with a portion of his force only under Rowland Hill and Beresford, Ustaritz and Cambo-les-Bains, his loss being slight, and thence pushed down the river towards Villefranque, where Soult barred his way across the road to Bayonne. The allied army was now divided into two portions by the Nive; and Soult from Bayonne at once took advantage of his central position to attack it with all his available force, first on the left bank and then on the right.[144] Desperate fighting now ensued, but owing to the intersected ground, Soult was compelled to advance slowly, and Wellington coming up with Beresford from the right bank, the French retired baffled.[144] Renewed French attacks on 13 December were also stopped. The losses in the four days' fighting in the battles before Bayonne (or battles of the Nive) were-Allies about 5,000, French about 7,000.[144][i]

1814

Operation resumed in February 1814 and Wellington went quickly over to the offensive. Hill on 14 and 15 February, after a battle of Garris, drove the French posts beyond the Joyeuse; and Wellington then pressed these troops back over the Bidouze and Gave de Mauleon to the Gave d'Oloron.[j] An amphibious landing with 8,000 troops at the mouth of the Adour secured a crossing over the river as a preliminary to the siege of Bayonne.[161] On 27 February, Wellington attacked Soult at Orthez and forced him to retreat towards Saint-Sever, which he reached on 28 February. The allied loss was about 2,000; the French 4,000 and 6 guns.[162] Beresford, with 12,000 men, was now sent to Bordeaux, which opened its gates as promised to the Allies. Driven by Hill from Aire-sur-l'Adour on 2 March 1814, Soult retired by Vic-en-Bigorre, where there was a combat (19 March), and Tarbes, where there was a severe action (20 March), to Toulouse behind the Garonne. He endeavored also to rouse the French peasantry against the Allies, but in vain, for Wellington's justice and moderation afforded them no grievances.[162][163]

The sortie from the besieged city of Bayonne, on 14 April 1814

On 8 April, Wellington crossed the Garonne and the Hers-Mort,[k] and attacked Soult at Toulouse on 10 April. Spanish attacks on Soult's heavily fortified positions were repulsed but Beresford's assault compelled the French to fall back.[162] On 12 April Wellington entered the city, Soult having retreated the previous day. The Allied loss was about 5,000, the French 3,000.[162]

On 13 April 1814 officers arrived with the announcement to both armies of the capture of Paris, the abdication of Napoleon, and the practical conclusion of peace; and on 18 April a convention, which included Suchet's force, was entered into between Wellington and Soult.[162] After Toulouse had fallen, the Allies and French, in a sortie from Bayonne on 14 April, each lost about 1,000 men, so that some 10,000 men fell after peace had virtually been made.[162] The Peace of Paris was formally signed at Paris on 30 May 1814.[162]

Aftermath

French victories of the Peninsular War inscribed on the Arc de Triomphe

At the end of the Peninsular War, British troops were partly sent to England, and partly embarked at Bordeaux for America for service in the final months of the American War of 1812. The Portuguese and Spanish recrossed the Pyrenees and the French army dispersed throughout France. Louis XVIII was restored to the French throne; and Napoleon was permitted to reside on the island of Elba, the sovereignty of which had been conceded to him by the allied powers.

King Joseph had been welcomed by Spanish afrancesados (Francophiles), who believed that collaboration with France would bring modernisation and liberty; an example was the abolition of the Spanish Inquisition. After the war, the remaining afrancesados were exiled to France.

The whole country had been pillaged, the Church had been ruined by its losses and society subjected to destabilizing change.[164][165] After the Peninsular War, the pro-independence traditionalists and liberals clashed in the Carlist Wars, as King Ferdinand VII ("the Desired One"; later "the Traitor King") revoked all the changes made by the independent Cortes in Cádiz. The experience in self-government led the later Libertadores (Liberators) to promote the independence of the Spain's American colonies. Portugal's position was more favorable than Spain's. Revolt had not spread to Brazil, there was no colonial struggle and there had been no attempt at political revolution.[166] The Portuguese Court's transfer to Rio de Janeiro initiated Brazil's state-building that produced its independence in 1822.

In all, the episode remains as the bloodiest event in Spain's modern history, doubling in relative terms the Spanish Civil War; it is open to debate among historians whether a transition from absolutism to liberalism in Spain at that moment would have been possible in the absence of war.[9]

Notes

^ Some accounts mark the Franco-Spanish invasion of Portugal as the beginning of the war (Glover 2001, p. 45).

^ Denotes the date of the general armistice between France and the Sixth Coalition (Glover 2001, p. 335).

^ Other names:

Basque: Iberiar Penintsulako Gerra ("Iberian Peninsular War") or Espainiako Independentzia Gerra ("Spanish War of Independence")

Catalan: Guerra del Francès ("War of the Frenchman")

French: Guerre d'Espagne et du Portugal ("War in Spain and in Portugal") or Campagne d'Espagne ("Spanish Campaign")

Galician: Guerra da Independencia española ("War of Spanish Independence")

Portuguese: Invasões Francesas ("French Invasions") or Guerra Peninsular ("Peninsular War")

Spanish: Many names, including the la Francesada, Guerra de la Independencia ("Independence War"), Guerra Peninsular ("Peninsular War"), Guerra de España ("War of Spain"), Guerra del Francés ("War of the French"), Guerra de los Seis Años ("Six Years' War"), Levantamiento y revolución de los españoles ("Rising and Revolution of the Spaniards")

^ There were a further 13,000 French troops besieged in Barcelona, Tortosa, Saguntun and other fortresses, who were under siege and not able to extract themselves to join Suchet at Figueras (Oman 1930, p. 425).

^ The Anglo-Italian battalions, the Calabrians and the Sicilian "Estero" regiment were sent to Sicily (Oman 1930, p. 429).

^ The bridge crosses the Urdains brook (a tributary of the Nive) just north of the Château d'Urdain.

^ George Bell, then a junior British officer in the 34th Foot recounted in his biography that the period of inaction in this area of an "Irish sentry who was found with a French and an English musket on his two shoulders, guarding a bridge over a brook on behalf of both armies. For he explained to the officer going the rounds that his French neighbour had gone off on his behalf, with his last precious half-dollar, to buy brandy for both, and had left his musket in pledge till his return. The French officer going his rounds on the other side of the brook then turned up, and explained that he had caught his sentry, without arms and carrying two bottles, a long way to the rear. If either of them reported what had happened to their colonels, both sentries would be court-martialled and shot. Wherefore both subalterns agreed to hush up the matter".[159]

^ On 11 December, Napoleon, beleaguered and desperate, agreed to a separate peace with Spain under the Treaty of Valençay, under which he would release and recognize Ferdinand in exchange for a complete cessation of hostilities. But the Spanish had no intention of trusting Napoleon and the fighting continued.[citation needed]

^ On the evening of 10 December, some 1,400 troops from three German battalions deserted in response to a secret message from the Duke of Nassau—one of the many German rulers who had surrendered following the Battle of Leipzig—ordering them to surrender to the Allies. In addition, Soult and Suchet lost the rest of their German units—another 3,000 men—as it was felt that they became unreliable. This left the Adour's defenders much depleted and incapable of further offensive action.[160]

^ "Gave" in the Pyrenees means a mountain stream or torrent.[144]

^ Contemporary British military sources and some secondary sources call this river the "Ers" (Robinson 1911, p. 97).

^ abcde Clodfelter 2017, p. 153.

^ The Portuguese Army of the Napoleonic Wars, by Rene Chartrand, Bill Younghusband, p. 16

^ ab Clodfelter 2017, p. 156.

^ Clodfelter 2017, p. 154.

^ abc Clodfelter 2017, p. 155.

^ Fraser 2008, p. 476.

^ abcde Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015. p. 157..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ abc Clodfelter 2017, p. 157.

^ ab Prados de la Escosura, Leandro; Santiago-Caballero, Carlos (April 2018). "The Napoleonic Wars: A Watershed in Spanish History?" (PDF). Working Papers on Economic History. European Historical Economic Society. 130: 18, 31.

^ Chandler, David. The Art of Warfare on Land. p. 164.

[full citation needed]

^ Fletcher 2003a, p. [page needed].

^ abcd Hindley 2010.

^ (Ellis 2014, p. 100) cites Owen Connelly (ed), "peninsular War", Historical dictionary, p. 387.

^ Payne 1973, pp. 432–433.

^ Chandler (1966), 588

^ Chandler (1966), 596

^ Chandler (1966), 597

^ ab Oman (2010), I, 7

^ ab Oman (2010), I, 8

^ Oman (2010), I, 9

^ Oman (2010), I, 26

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 22.

^ Gates (2002), 6-7

^ Oman (2010), I, 367

^ Oman (2010), I, 27

^ Oman (2010), I, 28

^ Oman (2010), I, 30

^ Chandler (1966), 599

^ abc Oman (2010), I, 31

^ ab Oman (2010), I, 32

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 37.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 38.

^ Chandler 1995, p. 610.

^ Esdaile 2003, pp. 302–303.

^ Gates 2009, p. 12.

^ Gates 2002, p. 162.

^ Chandler 1995, p. 611; Gates 2002, pp. 181–182.

^ Gates 2002, p. 61.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 67.

^ Chandler 1995, p. 614.

^ ab Esdaile 2003, p. 73.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 74.

^ Glover 2001, p. 53.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 77.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 84.

^ Chandler 1995, p. 617.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 87.

^ Richardson 1920, p. 343.

^ Gay 1903, p. 231.

^ Chandler 1995, p. 628.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 106.

^ Oman 1902, pp. 367–375.

^ Glover 2001, p. 55.

^ Chandler 1995, p. 631.

^ ab Martínez 1999, p. [page needed].

^ Oman 1902, p. 492.

^ Gates 2002, p. 108.

^ Fremont-Barnes 2002, p. 35.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 146.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 150.

^ Fletcher 1999, p. 97.

^ ab Gates 2002, p. 114.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 155.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 156.

^ ab Glover 2001, p. 89.

^ Bell, David A. "Napoleon's Total War". TheHistoryNet.com. Archived from the original on 2009-10-06.

^ abcdefghij Nuñez, A.; Smith, G.A. (7 December 2009). "The Cruel War in Spain: Napoleonic Wars: Peninsula Campaign: Wellington". Napolun.com. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

[unreliable source]

^ Gates 2009, p. 123.

^ Gates 2001, p. 138.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 178.

^ Gates 2001, p. 142.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 179.

^ Gates 2002, p. 177.

^ Guedalla 2005, p. 186.

^ Gates 2002, p. 94.

^ Gates 2002, pp. 194–196.

^ Gates 2002, p. 494.

^ Smith 1998, pp. 333–334This source listed Ballesteros' division in the Spanish order of battle

^ Gates 2002, pp. 197–199.

^ Gates 2002, p. 199.

^ Oman 1908, pp. 97–98.

^ Smith 1998, p. 336

^ Oman 1908, p. 98.

^ ab Oman 1908, p. 99.

^ Gates 2002, p. 204.

^ Oman 1908, p. 101.

^ Brandt 1999, p. 87.

^ ab McLynn 1997, pp. 396–406.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 239.

^ Laqueur 1975, pp. [page needed].

^ Rocca & Rocca 1815, p. [page needed].

^ Glover 2001, p. 10.

^ Chandler 1995, p. 746.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 270.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 271.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 280.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 220.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 282.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 283.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 284.

^ Argüelles 1970, p. 90.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 217.

^ Grehan, John. The Lines of Torres Vedras: The Cornerstone of Wellington's Strategy in the Peninsular War 1809–1812. Spellmount[full citation needed]

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 313.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 327.

^ Weller 1962, p. 144.

^ Gates 2001, pp. 32–33.

^ Weller 1962, pp. 145–146.

^ ab Southey 1837, p. 165.

^ Southey 1837, pp. 165, 170.

^ Southey 1837, pp. 172–180.

^ Gates 2001, p. 248.

^ Southey 1837, p. 241.

^ Anonymous 1825, p. 172.

^ Anonymous 1825, p. 174.

^ Rousset 1892, p. 21.

^ Esdaile 2003, p. 360.

^ Weller p 204