Doge's Palace

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (November 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Palazzo Ducale | |

| |

| Established | 1340 (1340) |

|---|---|

| Location | Piazza San Marco 1, 30124 Venice, Italy |

| Coordinates | 45°26′02″N 12°20′24″E / 45.4339°N 12.3400°E / 45.4339; 12.3400Coordinates: 45°26′02″N 12°20′24″E / 45.4339°N 12.3400°E / 45.4339; 12.3400 |

| Type | Art museum, Historic site |

| Visitors | 1,333,000 (2016)[1] |

| Director | Camillo Tonini |

| Website | palazzoducale.visitmuve.it |

The Doge's Palace (Italian: Palazzo Ducale; Venetian: Pałaso Dogal) is a palace built in Venetian Gothic style, and one of the main landmarks of the city of Venice in northern Italy. The palace was the residence of the Doge of Venice, the supreme authority of the former Venetian Republic, opening as a museum in 1923. Today, it is one of the 11 museums run by the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia.

Contents

1 History

2 Description

2.1 Exterior

2.2 Courtyard

2.3 Museo dell'Opera

2.4 Doge's apartments

2.5 Institutional chambers

2.6 Old Prison or Piombi

2.7 Bridge of Sighs and the New Prisons

3 Influences

3.1 Azerbaijan

3.2 Romania

3.3 United Kingdom

3.4 United States

3.4.1 19th-century imitations

3.4.2 20th-century imitations

3.4.3 21st-century imitations

4 References

5 Further reading

5.1 Primary sources

5.2 General sources

6 External links

History

Drawing of the Doge's Palace, late 14th century

In 810, Doge Agnello Participazio moved the seat of government from the island of Malamocco to the area of the present-day Rialto, when it was decided a palatium duci (Latin for "ducal palace") should be built. However, no trace remains of that 9th-century building as the palace was partially destroyed in the 10th century by a fire. The following reconstruction works were undertaken at the behest of Doge Sebastiano Ziani (1172–1178). A great reformer, he would drastically change the entire layout of the St. Mark's Square. The new palace was built out of fortresses, one façade to the Piazzetta, the other overlooking the St. Mark's Basin. Although only few traces remain of that palace, some Byzantine-Venetian architecture characteristics can still be seen at the ground floor, with the wall base in Istrian stone and some herring-bone pattern brick paving.

Political changes in the mid-13th century led to the need to re-think the palace's structure due to the considerable increase in the number of the Great Council's members. The new Gothic palace's constructions started around 1340, focusing mostly on the side of the building facing the lagoon. Only in 1424 did Doge Francesco Foscari decide to extend the rebuilding works to the wing overlooking the Piazzetta, serving as law-courts, and with a ground floor arcade on the outside, open first floor loggias running along the façade, and the internal courtyard side of the wing, completed with the construction of the Porta della Carta (1442).

In 1483, a violent fire broke out in the side of the palace overlooking the canal, where the Doge's Apartments were. Once again, an important reconstruction became necessary and was commissioned from Antonio Rizzo, who would introduce the new Renaissance language to the building's architecture. An entire new structure was raised alongside the canal, stretching from the ponte della Canonica to the Ponte della Paglia, with the official rooms of the government decorated with works commissioned from Vittore Carpaccio, Giorgione, Alvise Vivarini and Giovanni Bellini.

Another huge fire in 1547 destroyed some of the rooms on the second floor, but fortunately without undermining the structure as a whole. Refurbishment works were being held at the palace when on 1577 a third fire destroyed the Scrutinio Room and the Great Council Chamber, together with works by Gentile da Fabriano, Pisanello, Alvise Vivarini, Vittore Carpaccio, Giovanni Bellini, Pordenone, and Titian. In the subsequent rebuilding work it was decided to respect the original Gothic style, despite the submission of a neo-classical alternative designs by the influential Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio. However, there are some classical features — for example, since the 16th century, the palace has been linked to the prison by the Bridge of Sighs.

As well as being the ducal residence, the palace housed political institutions of the Republic of Venice until the Napoleonic occupation of the city in 1797, when its role inevitably changed. Venice was subjected first to French rule, then to Austrian, and finally in 1866 it became part of Italy. Over this period, the palace was occupied by various administrative offices as well as housing the Biblioteca Marciana and other important cultural institutions within the city.

By the end of the 19th century, the structure was showing clear signs of decay, and the Italian government set aside significant funds for its restoration and all public offices were moved elsewhere, with the exception of the State Office for the protection of historical Monuments, which is still housed at the palace's loggia floor. In 1923, the Italian State, owner of the building, entrusted the management to the Venetian municipality to be run as a museum. Since 1996, the Doge’s Palace has been part of the Venetian museums network, which has been under the management of the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia since 2008.

Description

Exterior

Facing the Grand Canal on the Piazzetta San Marco, with Doge's Palace on the left.

Palazzo Ducale, south colonnade, Venice, Italy. Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection

The oldest part of the palace is the wing overlooking the lagoon, the corners of which are decorated with 14th-century sculptures, thought to be by Filippo Calendario and various Lombard artists such as Matteo Raverti and Antonio Bregno. The ground floor arcade and the loggia above are decorated with 14th- and 15th-century capitals, some of which were replaced with copies during the 19th century.

In 1438–1442, Giovanni Bon and Bartolomeo Bon built and adorned the Porta della Carta, which served as the ceremonial entrance to the building. The name of the gateway probably derives either from the fact that this was the area where public scribes set up their desks, or from the nearby location of the cartabum, the archives of state documents. Flanked by Gothic pinnacles, with two figures of the Cardinal Virtues per side, the gateway is crowned by a bust of Mark the Evangelist over which rises a statue of Justice with her traditional symbols of sword and scales. In the space above the cornice, there is a sculptural portrait of the Doge Francesco Foscari kneeling before the Lion of Saint Mark. This is, however, a 19th-century work by Luigi Ferrari, created to replace the original destroyed in 1797.

Nowadays, the public entrance to the Doge's Palace is via the Porta del Frumento, on the waterfront side of the building.

Courtyard

Courtyard of the Doge's Palace, facing the San Marco basilica.

The Scala dei Giganti, flanked by Mars and Neptune.

The north side of the courtyard is closed by the junction between the palace and St. Mark’s Basilica, which used to be the Doge’s chapel. At the center of the courtyard stand two well-heads dating from the mid-16th century.

In 1485, the Great Council decided that a ceremonial staircase should be built within the courtyard. The design envisaged a straight axis with the rounded Foscari Arch, with alternate bands of Istrian stone and red Verona marble, linking the staircase to the Porta della Carta, and thus producing one single monumental approach from the Piazza into the heart of the building. Since 1567, the Giants’ Staircase is guarded by Sansovino’s two colossal statues of Mars and Neptune, which represents Venice’s power by land and by sea, and therefore the reason for its name. Members of the Senate gathered before government meetings in the Senator’s Courtyard, to the right of the Giants’ Staircase.

Museo dell'Opera

Over the centuries, the Doge’s Palace has been restructured and restored countless times. Due to fires, structural failures, and infiltrations, and new organizational requirements and modifications or complete overhaulings of the ornamental trappings there was hardly a moment in which some kind of works have not been under way at the building. From the Middle Ages, the activities of maintenance and conservation were in the hands of a “technical office”, which was in charge of all such operations and oversaw the workers and their sites: the Opera, or fabbriceria or procuratoria. After the mid-19th century, the Palace seemed to be in such a state of decay that its very survival was in question; thus from 1876 a major restoration plan was launched. The work involved the two facades and the capitals belonging to the ground-floor arcade and the upper loggia: 42 of these, which appeared to be in a specially dilapidated state, were removed and replaced by copies. The originals, some of which were masterpieces of Venetian sculpture of the 14th and 15th centuries, were placed, together with other sculptures from the facades, in an area specifically set aside for this purpose: the Museo dell’Opera. After undergoing thorough and careful restoration works, they are now exhibited, on their original columns, in these 6 rooms of the museum, which are traversed by an ancient wall in great blocks of stone, a remnant of an earlier version of the Palace. The rooms also contain fragments of statues and important architectural and decorative works in stone from the facades of the Palace.

Doge's apartments

The rooms in which the Doge lived were always located in this area of the palace, between the Rio della Canonica – the water entrance to the building – the present-day Golden Staircase and the apse of St. Mark’s Basilica. The disastrous fire in this part of the building in 1483 made important reconstruction work necessary, with the Doge’s apartments being completed by 1510. The core of these apartments forms a prestigious, though not particularly large, residence, given that the rooms nearest the Golden Staircase had a mixed private and public function. In the private apartments, the Doge could set aside the trappings of office to retire at the end of the day and dine with members of his family amidst furnishings that he had brought from his own house (and which, at his death, would be promptly removed to make way for the property of the new elected Doge).

- The Scarlet Chamber possibly takes its name from the color of the robes worn by the Ducal advisors and counsellors for whom it was the antechamber. The carved ceiling, adorned with the armorial bearings of Doge Andrea Gritti, is part of the original décor, probably designed by Biagio and Pietro da Faenza. Amongst the wall decoration, two frescoed lunettes are particular worthy of attention: one by Giuseppe Salviati, the other by Titian.

- The “Scudo” Room has this name from the coat-of-arms of the reigning Doge which was exhibited here while he granted audiences and received guests. The coat-of-arms currently on display is that of Ludovico Manin, the Doge reigning when the Republic of St. Mark came to an end in 1797. This is the largest room in the Doge’s apartments, and runs the entire width of this wing of the palace. The hall was used as a reception chamber and its decoration with large geographical maps was designed to underline the glorious tradition that was at the very basis of Venetian power. The two globes in the center of the hall date from the same period: one shows the sphere of heavens, the other the surface of Earth.

- The Erizzo Room owes its name to Doge Francesco Erizzo (1631–1646) and is decorated in the same way as the preceding ones: a carved wood ceiling, with gilding against a light-blue background, and a Lombardy-school fireplace. From here, a small staircase leads up to a window that gave access to a roof garden.

- The Stucchi or Priùli Room has a double name due to both the stucco works that adorn the vault and lunettes, dating from the period of Doge Marino Grimani (1595–1605), and the presence of the armorial bearings of Doge Antonio Priùli (1618–1623), which are to be seen on the fireplace, surmounted by allegorical figures. The stucco-works on the walls and ceiling were later commissioned by another Doge Pietro Grimani (1741–1752). Various paintings representing the life of Jesus Christ are present in this room, as well as a portrait of the French King Henry III (perhaps by Tintoretto) due to his visit to the city in 1574 on his way from Poland to take up the French throne left vacant with the death of his brother Charles IX.

- Directly linked to the Shield Hall, the Philosophers’ Room takes its name from the twelve pictures of ancient philosophers which were set up here in the 18th century, to be later replaced with allegorical works and portraits of Doges. To the left, a small doorway leads to a narrow staircase, which enabled the Doge to pass rapidly from his own apartments to the halls on the upper floors, where the meetings of the Senate and the Great Council were held. Above the other side of this doorway there is an important fresco of St. Christopher by Titian.

- The Corner Room's name comes from the presence of various paintings depicting Doge Giovanni Corner (1625–1629). The fireplace, made out of Carrara marble, is decorated with a frieze of winged angels on dolphins around a central figure of St. Mark’s Lion. Like the following room, this served no specific function; set aside for the private use of the Doge.

- The Equerries Room was the main access to the Doge’s private apartments. The palace equerries were appointed for life by the Doge himself and had to be at his disposal at any time.

Institutional chambers

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Interior of the Doge's Palace (Venice) by zone. |

Palazzo Ducale, Sala del Senato, Venice, Italy. Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection

- The Square Atrium served as a waiting room, the antechamber to various halls. The decoration dates from the 16th century, during the reign of Doge Girolamo Priuli (1486–1567), who appears in Tintoretto’s ceiling painting with the symbols of his office, and accompanied by scenes of biblical stories and allegories of the four seasons, probably by Tintoretto’s workshop, Girolamo Bassano and Veronese.

- The Four Doors Room was the formal antechamber to the more important rooms in the palace, and the doors which give it its name are ornately framed in precious Eastern marbles; each is surmounted by an allegorical sculptural group that refers to the virtues which should inspire those who took on the government responsibilities. The present decoration is a work by Antonio da Ponte and design by Andrea Palladio and Giovan Antonio Rusconi. Painted by Tintoretto from 1578 onwards, the frescoes of mythological subjects and of the cities and regions under Venetian dominion were designed to show a close link between Venice’s foundation, its independence, and the historical mission of the Venetian aristocracy. Amongst the paintings on the walls, one that stands out is Titian’s portrait of Doge Antonio Grimani (1521–1523). On the easel stands a painting by Tiepolo portraying Venice receiving the gifts of the sea from Neptune.

Neptune Offering Gifts to Venice (1748–1750) by Giovan Battista Tiepolo

- Antechamber to the Hall of the Full College was the formal antechamber where foreign ambassadors and delegations waited to be received by the Full College, delegated by the Senate to deal with foreign affairs. This room was restored after the 1574 fire and so was its decorations, with stucco-works and ceiling frescoes. The central fresco by Veronese shows Venice distributing honors and rewards. The top of the walls is decorated with a fine frieze and other sumptuous fittings, including the fireplace between the windows and the fine doorway leading into the Hall of the Full College, whose Corinthian columns bear a pediment surmounted by a marble sculpture showing the female figure of Venice resting on a lion and accompanied by allegories of Glory and Concord. Next to the doorways are four canvases that Tintoretto painted for the Square Atrium, but which were brought here in 1716 to replace the original leather wall panelling. Each of the mythological scenes depicted is also an allegory of the Republic’s government.

- The Council Chamber: the Full College was mainly responsible for organizing and coordinating the work of the Venetian Senate, reading dispatches from ambassadors and city governors, receiving foreign delegations and promoting other political and legislative activity. Alongside these shared functions, each body had their own particular mandates, which made this body a sort of “guiding intelligence” behind the work of the Senate, especially in foreign affairs. The decorations were designed by Andrea Palladio to replace that destroyed in the 1574 fire; the wood panelling of the walls and end tribune and the carved ceiling are the work of Francesco Bello and Andrea da Faenza. The paintings in the ceiling were commissioned from Veronese, who completed them between 1575 and 1578. This ceiling is one of the artist’s masterpieces and celebrates the Good Government of the Republic, together with the Faith on which it rests and the Virtues that guide and strengthen it. Other paintings are by Tintoretto and show various Doges with the Christ, the Virgin and saints.

- The Senate Chamber was also known as the Sala dei Pregadi, because the Doge asked the members of the Senate to take part in the meetings held here. The Senate which met in this chamber was one of the oldest public institutions in Venice; it had first been founded in the 13th century and then gradually evolved over time, until by the 16th century it was the body mainly responsible for overseeing political and financial affairs in such areas as manufacturing industries, trade and foreign policy. In the works produced for this room by Tintoretto, Christ is clearly the predominant figure; perhaps a reference to the Senate ‘conclave’ which elected the Doge, seen as being under the protection of the Son of God. The room also contains four paintings by Jacopo Palma il Giovane, which are linked with specific events of the Venetian history.

- The Chamber of the Council of Ten takes its name from the Council of Ten which was set up after a conspiracy in 1310, when Bajamonte Tiepolo and other noblemen tried to overthrow the institutions of the State. The ceiling decoration is a work by Gian Battista Ponchino, with the assistance of a young Veronese and Gian Battista Zelotti. Carved and gilded, the ceiling is divided into 25 compartments decorated with images of divinities and allegories intended to illustrate the power of the Council of Ten that was responsible for punishing the guilty and freeing the innocent.

- The Compass Room is dedicated to the administration of justice; its name comes from the large wooden compass surmounted by a statue of Justice, which stands in one corner and hides the entrance to the rooms of the Three Heads of the Council of Ten and the State Inquisitors. This room was the antechamber where those who had been summoned by these powerful magistrates waited to be called and the decoration was intended to underline the solemnity of the Republic’s legal machinery, dating from the 16th century. The ceiling paintings are by Veronese and the large fireplace was designed by Sansovino. From this room, one can pass to the Armoury and the New Prisons, on the other side of the Bridge of Sighs, or go straight down the Censors’ Staircase to pass into the rooms housing the councils of justice on the first floor.

- In the Venetian language, Liagò means a terrace or balcony enclosed by glass. This particular example was a sort of corridor and meeting-place for patrician members of the Great Council in the intervals between their discussions of government business.

- The Chamber of Quarantia Civil Vecchia: originally a single 40-man-council which wielded substantial political and legislative power, the Quarantia was during the course of the 15th century divided into three separate councils. This room was restored in the 17th century; the fresco fragment to the right of the entrance is the only remnant of the original decorations.

- The Guariento Room's name is due to the fact it houses a fresco painted by the Paduan artist Guariento around 1365. Almost completely destroyed in the 1577 fire, the remains of that fresco were, in 1903, rediscovered under the large canvas Il Paradiso which Tintoretto was commissioned to paint.

- Restructured in the 14th century, the Chamber of the Great Council was decorated with a fresco by Guariento and later with works by the most famous artists of the period, including Gentile da Fabriano, Pisanello, Alvise Vivarini, Vittore Carpaccio, Giovanni Bellini, Pordenone and Titian. 53 meters long and 25 meters wide, this is not only the largest chamber in the Doge’s Palace, but also one of the largest rooms in Europe. Here, meetings of the Great Council were held, the most important political body in the Republic. A very ancient institution, this Council was made up of all the male members of patrician Venetian families over 25 years old, irrespective of their individual status, merits or wealth. This was why, in spite of the restrictions in its powers that the Senate introduced over the centuries, the Great Council continued to be seen as bastion of Republican equality. Soon after work on the new hall had been completed, the 1577 fire damaged not only this Chamber but also the Scrutinio Room. The structural damage was soon restored, respecting the original layout, and all works were finished within few years, ending in 1579–80. The decoration of the restored structure involved artists such as Veronese, Jacopo and Domenico Tintoretto, and Jacopo Palma il Giovane. The walls were decorated with episodes of the Venetian history, with particular reference to the city’s relations with the papacy and the Holy Roman Empire, while the ceiling was decorated with the Virtues and individual examples of Venetian heroism, and a central panel containing an allegorical glorification of the Republic. Facing each other in groups of six, the twelve wall paintings depict acts of valor or incidents of war that had occurred during the city’s history. Immediately below the ceiling runs a frieze with portraits of the first 76 doges (the portraits of the others are to be found in the Scrutinio Room); commissioned from Tintoretto, most of these paintings are in fact the work of his son. Each Doge holds a scroll bearing a reference to his most important achievements, while Doge Marin Faliero, who attempted a coup d’état in 1355, is represented simply by a black cloth as a traitor to the Republic. One of the long walls, behind the Doge’s throne, is occupied by the longest canvas painting in the world, Il Paradiso, which Tintoretto and his workshop produced between 1588 and 1592.

- The Scrutinio Room is in the wing built between the 1520s and 1540s during the dogate of Francesco Foscari (1423–57), facing the Piazzeta. It was initially intended to house the precious manuscripts left to the Republic by Petrarch and Bessarione (1468); indeed, it was originally known as the Library. In 1532, it was decided that the Chamber should also hold the electoral counting and/or deliberations that assiduously marked the rhythm of Venetian politics, based on an assembly system whose epicenter was the nearby Great Council Chamber. After the construction of Biblioteca Marciana though, this room was used solely for elections. The present decorations date from between 1578 and 1615, after the 1577 fire. Episodes of military history in the various compartments glorify the exploits of the Venetians, with particular emphasis on the conquest of the maritime empire; the only exception being the last oval, recording the taking of Padua in 1405.

- The Quarantia Criminale Chamber and the Cuoi Room were used for the administration of justice. The Quarantia Criminal was set up in the 15th century and dealt with cases of criminal law. It was a very important body as its members also had legislative powers.

- The Magistrato alle Leggi Chamber housed the Magistratura dei Conservatori ed esecutori delle leggi e ordini degli uffici di San Marco e di Rialto. Created in 1553, this authority was headed by three of the city’s patricians and was responsible for making sure the regulations concerning the practice of law were observed.

- The State Censors were set up in 1517 by Marco Giovanni di Giovanni, a cousin of Doge Andrea Gritti (1523–1538) and nephew of the great Francesco Foscari. The title and duties of the Censors resulted from the cultural and political upheavals that are associated with Humanism. In fact, the Censors were not judges as such, but more like moral consultants, their main task being the suppression of electoral fraud and protection of the State’s public institutions. On the walls of the Censors' Chamber hang a number of Domenico Tintoretto’s portraits of these magistrates, and below the armorial bearings of some of those who held the position.

- The State Advocacies' Chamber is decorated with paintings representing some of the Avogadori di Común venerating the Virgin, the Christ and various saints. The three members, the Avogadori, were the figures who safeguarded the very principle of legality, making sure that the laws were applied correctly. They were also responsible for preserving the integrity of the city’s patrician class, verifying the legitimacy of marriages and births inscribed in the Golden Book.

- The "Scrigno" Room: the Venetian nobility as a caste came into existence because of the “closure” of admissions to the Great Council in 1297; however, it was only in the 16th century that formal measures were taken to introduce restrictions that protected the status of that aristocracy: marriages between nobles and commoners were forbidden and greater controls were set up to check the validity of aristocratic titles. There was also a Silver Book, which registered all those families that not only had the requisites of “civilization” and “honor”, but could also show that they were of ancient Venetian origin; such families furnished the manpower for the State bureaucracy - and particularly, the chancellery within the Doge’s Palace itself. Both books were kept in a chest in this room, inside a cupboard that also contained all the documents proving the legitimacy of claims to be inscribed therein.

- Chamber of the Navy Captains: made up of 20 members from the Senate and the Great Council, the Milizia da Mar, first set up in the mid-16th century, was responsible for recruiting crews necessary for Venice’s war galleys. Another similar body, entitled the Provveditori all’Armar, was responsible for the actual fitting and supplying of the fleet. The furnishings are from the 16th century, while the wall torches date from the 18th century.

Old Prison or Piombi

Prior to the 12th century there were holding cells within the Doge's Palace but during the 13th and fourteenth centuries more prison spaces were created to occupy the entire ground floor of the southern wing.

Again these layouts changed in c.1540 when a compound of the ground floor of the eastern wing was built. Due to the dark, damp and isolated qualities of they came to be known as the Pozzi (the Wells).[2]

In 1591 yet more cells were built in the upper eastern wing. Due to their position, directly under the lead roof, they were known as Piombi.[3] Among the famous inmates of the prison were Silvio Pellico and Giacomo Casanova. The latter in his biography describes escaping through the roof, re-entering the palace, and exiting through the Porta della Carta.

Bridge of Sighs and the New Prisons

Capital #12 in the porch (counting as #0 the one at the corner near the Bridge of Sighs): "Allegories of Virtues and Vices" - "Falsa fides in me semper est".

A corridor leads over the Bridge of Sighs, built in 1614 to link the Doge’s Palace to the structure intended to house the New Prisons.[4] Enclosed and covered on all sides, the bridge contains two separate corridors that run next to each other. That which visitors use today linked the Prisons to the chambers of the Magistrato alle Leggi and the Quarantia Criminal; the other linked the prisons to the State Advocacy rooms and the Parlatorio. Both corridors are linked to the service staircase that leads from the ground floor cells of the Pozzi to the roof cells of the Piombi.

The famous name of the bridge dates from the Romantic period and was supposed to refer to the sighs of prisoners who, passing from the courtroom to the cell in which they would serve their sentence, took a last look at freedom as they glimpsed the lagoon and San Giorgio through the small windows. In the mid-16th century it was decided to build a new structure on the other side of the canal to the side of the palace which would house prisons and the chambers of the magistrates known as the Notte al Criminal. Ultimately linked to the palace by the Bridge of Sighs, the building was intended to improve the conditions for prisoners with larger and more light-filled and airy cells. However, certain sections of the new prisons fall short of this aim, particularly those laid out with passageways on all sides and those cells which give onto the inner courtyard of the building. In keeping with previous traditions, each cell was lined with overlapping planks of larch that were nailed in place.

Madonna col bambino, the painting stolen on 9 October 1991 by Vincenzo Pipino after he hid in a cell in the New Prisons

The only art theft from the Doge's Palace was executed on 9 October 1991 by Vincenzo Pipino, who hid in one of the cells in the New Prisons after lagging behind a tour group, then crossed the Bridge of Sighs in the middle of the night to the Sala di Censori. In that room was the Madonna col bambino, a work symbolic of "the power of the Venetian state" painted in the early 1500s by a member of the Vivarini school.[5] By the next morning, it was in the possession of the Mala del Brenta organized crime group. The painting was recovered by the police on 7 November 1991.[6]

Influences

Azerbaijan

The Ismailiyya building in Baku, which at present serves as the Presidium of the Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, was styled after the Doge's Palace.[citation needed]

Romania

The Central rail station, in Iași, built in 1870, had as a model the architecture of the Doge's Palace. On the central part, there is a loggia with five arcades and pillars made of curved stone, having at the top three ogives.

United Kingdom

The western façade of Templeton's Carpet Factory

There are a number of 19th-century imitations of the palace's architecture in the United Kingdom, for example:

- the Wool Exchange, Bradford,

- the Wedgwood Institute, Burslem,

- the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh

- the Templeton's Carpet Factory, Glasgow.

These revivals of Venetian Gothic were influenced by the theories of John Ruskin, author of the three-volume The Stones of Venice, which appeared in the 1850s.

United States

19th-century imitations

National Academy of Design (1863–65), one of many Gothic Revival buildings modeled on the Doge's Palace

The Montauk Club in Park Slope, Brooklyn (1889) imitates elements of the palace's architecture, although the architect is usually said to have been inspired by another Venetian Gothic palace, the Ca' d'Oro.

The elaborate arched facade of the 1895 building of Congregation Ohabai Shalome in San Francisco is a copy in painted redwood of the Doge's Palace.

20th-century imitations

The ornate gothic style of the Doge's Palace (and other similar palaces throughout Italy) is replicated in the Hall of Doges at the Davenport Hotel in Spokane, Washington by architect Kirtland Cutter.

The facade of the building is replicated at the Italy Pavilion in Epcot at the Walt Disney World Resort in Orlando, Florida.

Along with other Venetian landmarks, the palace is imitated in The Venetian, Las Vegas and its sister resort The Venetian Macao.

21st-century imitations

The Doge's Palace was recreated and is playable in the 2009 video game, Assassin's Creed II. In the game, one of the objectives is to get protagonist Ezio Auditore da Firenze to fly a hang-glider built for him by Leonardo da Vinci into the Palazzo Ducale in order to prevent a Templar plot to kill the current Doge, Giovanni Mocenigo. Though he arrives too late to prevent the Doge from being poisoned, he does manage to kill the assassin, Carlo Grimaldi, who was a member of the Council of Ten.

The interior of the Doge's Palace taken c. 1900.

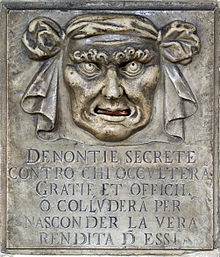

A "Lion's Mouth" postbox for anonymous denunciations at the Doge's Palace. Text translation: "Secret denunciations against anyone who will conceal favors and services or will collude to hide the true revenue from them".

References

^ "Visitor Figures 2016" (PDF). The Art Newspaper Review. April 2017. p. 14. Retrieved 23 March 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Geltner, G., 2008. The Medieval Prison: A Social History. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (pp.12)

^ Geltner, G., 2008. The Medieval Prison: A Social History. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (pp.12)

^ Geltner, G., 2008. The Medieval Prison: A Social History. Princeton: Princeton University Press (pp. 13)

^ Davis & Wolman 2014.

^ Davis, Joshua; Wolman, David (26 October 2014). Bearman, Joshuah, ed. "Pipino: Gentleman Thief". Epic Magazine. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

Further reading

Primary sources

de Bardi, Gerolamo (1587). Dichiaratione di tutte le istorie che si contengono nei quadri posti novamente nelle sale dello Scrutinio et del gran Consiglio del Palagio Ducale della Serenissima Republica di Vinegia, nella quale si ha piena intelligenza delle più segnalate vittorie, conseguite di varie nationi del mondo dai Vinitiani. Venezia: Felice Valgrisio.

Cadorin, Giuseppe (1838). Pareri di XV architetti e notizie storiche intorno al palazzo ducale di Venezia. Venezia.

ICCU: ITICCUSBL415914

Leopoldo Cicognara (1840). Le fabbriche e i monumenti cospicui di Venezia. Antonelli.

ICCU: ITICCUVEA1062363

Giovanni Battista Cipelli (1554). De exemplis illustrium virorum Venetae civitatis atque aliarum gentium. VIII.

Gallicciolli, Giovanni Battista (1795). Delle Memorie Venete Antiche Profane Ed Ecclesiastiche. II. Fracasso.

ICCU: ITICCUMILE14246

Magrini, Antonio (1845). Memorie intorno la vita e le opere di Andrea Palladio. Padova: Tipografia del Seminario.

ICCU: ITICCUVEA099770

Francesco Molino. Memorie delle cose successe a' suoi tempi dal 1558 al 1598.

Jacopo Morelli (1820). Operette. I. Venezia.

Carlo Ridolfi; Giuseppe Vedova (1648). Le meraviglie dell'arte. 2. Padova.

Sagornino, Johanni (1765). Chronicon Venetum Omnium Quae Circum Feruntur Vetustissimum (in Latin). Venezia.

Sansovino, Francesco (1663). Venetia, città nobilissima et singolare. Venezia: Stefano Curti.

ICCU: ITICCUPUVE00194

Marin Sanudo il Giovane. Vite dei Dogi.

Marin Sanudo il Giovane. Diarii.

Pietro Selvatico (1847). Sulla architettura e scultura in Venezia.

ICCU: ITICCULO1327537

Temanza, Tommaso (1778). Vite de' più celebri Architetti e Scultori Veneziani che fiorirono nel secolo decimosesto. I. Venezia: C. Palese.

ICCU: ITICCUVIAE00348

Zanetti, Anton Maria (1771). Della pittura Veneziana e delle opere pubbliche de Veneziani maestri. I. Venezia: Giambatista Albrizzi.

ICCU: ITICCURMRE00503

General sources

Bianchi, Eugenia; Righi, Nadia; Terzaghi, Maria Cristina (1997). Il Palazzo Ducale di Venezia. Milano. ISBN 88-435-5921-4.

Boulton, Susie; Catling, Christopher. Venezia e il Veneto. Mondadori. pp. 84–89. ISBN 978-88-04-43092-6.

Brusegan, Marcello (2007). I palazzi di Venezia. Roma: Newton & Compton. pp. 121–142. ISBN 978-88-541-0820-2.

Giuseppe Cappelletti (1853). Storia della Repubblica di Venezia. Antonelli.

Devitini, Alessia; Zuffi, Stefano; Castria, Francesca. Venezia. Electa. ISBN 978-88-370-2149-8.

Franzoi, Umberto (1983). Itinerari segreti nel Palazzo Ducale di Venezia. Treviso.

ICCU: ITICCUCFI001113

Franzoi, Umberto (1997). Le Prigioni di Palazzo Ducale a Venezia. Milano. ISBN 978-88-435-6238-1.

Franzoi, Umberto (1982). Storia e leggenda del Palazzo Ducale di Venezia. Venezia. ISBN 978-88-7666-037-5.

Franzoi, Umberto; Pignatti, T.; Wolters, W. (1990). Il Palazzo Ducale di Venezia. Treviso. ISBN 978-88-7666-065-8.

Knezevich, Michela (1993). Il Palazzo Ducale di Venezia. Milano. ISBN 978-88-435-4464-6.

Manno, Antonio (1996). Palazzo ducale guida al Museo dell'Opera. Venezia. ISBN 88-86502-37-0.

Mariacher, Giovanni (1950). Il Palazzo Ducale di Venezia. Firenze: Del Turco.

ICCU: ITICCUMIL425080

Morgagni, Alessandra (1997). Venezia. Electa. pp. 50–65. ISBN 978-88-435-5953-4.

Serra, Luigi (1933). Il Palazzo Ducale di Venezia. Roma: Libreria dello Stato.

ICCU: ITICCUIEI269592

Zanotto, Francesco (1853). Il Palazzo ducale di Venezia. 1. illustrato da Francesco Zanotto. Venezia: Antonelli.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Doge's Palace (Venice). |

- Official website

- Palazzo Ducale on Smarthistory