Maria Theresa

| Maria Theresa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait by Martin van Meytens, 1759 | |||||

Holy Roman Empress German Queen | |||||

| Reign | 13 September 1745 – 18 August 1765 | ||||

| Coronation | 13 September 1745 | ||||

Archduchess of Austria Queen of Hungary and Croatia | |||||

| Reign | 20 October 1740 – 29 November 1780 | ||||

| Coronation | 25 June 1741 | ||||

| Predecessor | Charles III | ||||

| Successor | Joseph II | ||||

| Queen of Bohemia | |||||

| Reign | 20 October 1740 – 19 December 1741 | ||||

| Predecessor | Charles II | ||||

| Successor | Charles Albert | ||||

| Reign | 12 May 1743 – 29 November 1780 | ||||

| Coronation | 12 May 1743 | ||||

| Predecessor | Charles Albert | ||||

| Successor | Joseph II | ||||

| Born | (1717-05-13)13 May 1717 Vienna, Austria | ||||

| Died | 29 November 1780(1780-11-29) (aged 63) Vienna, Austria | ||||

| Burial | Imperial Crypt | ||||

| Spouse | Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor (m. 1736; died 1765) | ||||

| Issue | See

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Habsburg | ||||

| Father | Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor | ||||

| Mother | Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (German: Maria Theresia [maˈʁiːa teˈʁeːzi̯a]; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was the only female ruler of the Habsburg dominions and the last of the House of Habsburg. She was the sovereign of Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Bohemia, Transylvania, Mantua, Milan, Lodomeria and Galicia, the Austrian Netherlands and Parma. By marriage, she was Duchess of Lorraine, Grand Duchess of Tuscany and Holy Roman Empress.

She started her 40-year reign when her father, Emperor Charles VI, died in October 1740. Charles VI paved the way for her accession with the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 and spent his entire reign securing it. He neglected the advice of Prince Eugene of Savoy that a strong military and a rich treasury were more important than mere signatures. Eventually, he left behind a weakened and impoverished state, particularly due to the War of the Polish Succession and the Russo-Turkish War (1735–1739). Moreover, upon his death, Saxony, Prussia, Bavaria, and France all repudiated the sanction they had recognised during his lifetime. Frederick II of Prussia (who became Maria Theresa's greatest rival for most of her reign) promptly invaded and took the affluent Habsburg province of Silesia in the seven-year conflict known as the War of the Austrian Succession. In defiance of the grave situation, she managed to secure the vital support of the Hungarians for the war effort. Over the course of the war, despite the loss of Silesia and a few minor territories in Italy, Maria Theresa successfully defended her rule over most of the Habsburg empire. Maria Theresa later unsuccessfully tried to reconquer Silesia during the Seven Years' War.

Maria Theresa and her husband, Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor, had eleven daughters, including the Queen of France, the Queen of Naples and Sicily, the Duchess of Parma, and five sons, including two Holy Roman Emperors, Joseph II and Leopold II. Of the sixteen children, ten survived to adulthood. Though she was expected to cede power to Francis and Joseph, both of whom were officially her co-rulers in Austria and Bohemia, Maria Theresa was the absolute sovereign who ruled with the counsel of her advisers.

Maria Theresa promulgated institutional, financial and educational reforms, with the assistance of Wenzel Anton of Kaunitz-Rietberg, Count Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz and Gerard van Swieten. She also promoted commerce and the development of agriculture, and reorganised Austria's ramshackle military, all of which strengthened Austria's international standing. However, she despised the Jews and the Protestants, and on certain occasions she ordered their expulsion to remote parts of the realm. She also advocated for the state church and refused to allow religious pluralism. Consequently, her regime was branded as intolerant.

Contents

1 Birth and early life

2 Marriage

3 Ascension

4 War of the Austrian Succession

5 Seven Years' War

6 Family life

7 Religious views and policies

7.1 Jesuits

7.2 Jews and Protestants

8 Reforms

8.1 Institutional

8.2 Medicine

8.3 Law

8.4 Education

8.5 Censorship

8.6 Economy

9 Late reign

10 Death and legacy

11 Full title

12 See also

13 Notes

14 References

15 Bibliography

16 External links

Birth and early life

Three-year-old Maria Theresa in the gardens of Hofburg Palace

The second and eldest surviving child of Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI and Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Archduchess Maria Theresa was born on 13 May 1717 in Vienna, a year after the death of her elder brother, Archduke Leopold,[1] and was baptised on that same evening. The dowager empresses, her aunt Wilhelmine Amalia of Brunswick-Lüneburg and grandmother Eleonor Magdalene of the Palatinate-Neuburg, were her godmothers.[2] Most descriptions of her baptism stress that the infant was carried ahead of her cousins, Maria Josepha and Maria Amalia, the daughters of Charles VI's elder brother and predecessor, Joseph I, before the eyes of their mother, Wilhelmine Amalia.[3] It was clear that Maria Theresa would outrank them,[3] even though their grandfather, Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, had his sons sign the Mutual Pact of Succession, which gave precedence to the daughters of the elder brother.[4] Her father was the only surviving male member of the House of Habsburg and hoped for a son who would prevent the extinction of his dynasty and succeed him. Thus, the birth of Maria Theresa was a great disappointment to him and the people of Vienna; Charles never managed to overcome this feeling.[4]

Maria Theresa replaced Maria Josepha as heir presumptive to the Habsburg realms the moment she was born; Charles VI had issued the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 which had placed his nieces behind his own daughters in the line of succession.[5] Charles sought the other European powers' approval for disinheriting his nieces. They exacted harsh terms: in the Treaty of Vienna (1731), Great Britain demanded that Austria abolish the Ostend Company in return for its recognition of the Pragmatic Sanction.[6] In total, Great Britain, France, Saxony, United Provinces, Spain, Prussia, Russia, Denmark, Sardinia, Bavaria and the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire recognised the sanction.[7] France, Spain, Saxony, Bavaria and Prussia later reneged.

Archduchess Maria Theresa, by Andreas Möller.

Little more than a year after her birth, Maria Theresa was joined by a sister, Maria Anna, and another one, named Maria Amalia, was born in 1724.[8] The portraits of the imperial family show that Maria Theresa resembled Elisabeth Christine and Maria Anna.[9] The Prussian ambassador noted that she had large blue eyes, fair hair with a slight tinge of red, a wide mouth and a notably strong body.[10] Unlike many other members of the House of Habsburg, neither Maria Theresa's parents nor her grandparents were closely related to each other.[note 1]

Maria Theresa was a serious and reserved child who enjoyed singing and archery. She was barred from horse riding by her father, but she would later learn the basics for the sake of her Hungarian coronation ceremony. The imperial family staged opera productions, often conducted by Charles VI, in which she relished participating.[11] Her education was overseen by Jesuits. Contemporaries thought her Latin to be quite good, but in all else, the Jesuits did not educate her well. Her spelling and punctuation were unconventional and she lacked the formal manner and speech which had characterised her Habsburg predecessors.[note 2] Maria Theresa developed a close relationship with Countess Marie Karoline von Fuchs-Mollard, who taught her etiquette. She was educated in drawing, painting, music and dancing – the disciplines which would have prepared her for the role of queen consort.[12] Her father allowed her to attend meetings of the council from the age of 14 but never discussed the affairs of state with her.[13] Even though he had spent the last decades of his life securing Maria Theresa's inheritance, Charles never prepared his daughter for her future role as sovereign.[14]

Marriage

The question of Maria Theresa's marriage was raised early in her childhood. Leopold Clement of Lorraine was first considered to be the appropriate suitor, and he was supposed to visit Vienna and meet the Archduchess in 1723. These plans were forestalled by his death from smallpox.[15]

Leopold Clement's younger brother, Francis Stephen, was invited to Vienna. Even though Francis Stephen was his favourite candidate for Maria Theresa's hand,[16] the Emperor considered other possibilities. Religious differences prevented him from arranging his daughter's marriage to the Protestant prince Frederick of Prussia.[17] In 1725, he betrothed her to Charles of Spain and her sister, Maria Anna, to Philip of Spain. Other European powers compelled him to renounce the pact he had made with the Queen of Spain, Elisabeth Farnese. Maria Theresa, who had become close to Francis Stephen, was relieved.[18][19]

Maria Theresa and Francis Stephen at their wedding breakfast, by Martin van Meytens. Charles VI (in the red-plumed hat) is seated at the center of the table.

Francis Stephen remained at the imperial court until 1729, when he ascended the throne of Lorraine,[17] but was not formally promised Maria Theresa's hand until 31 January 1736, during the War of the Polish Succession.[20]Louis XV of France demanded that Maria Theresa's fiancé surrender his ancestral Duchy of Lorraine to accommodate his father-in-law, Stanisław I, who had been deposed as King of Poland.[note 3] Francis Stephen was to receive the Grand Duchy of Tuscany upon the death of childless Grand Duke Gian Gastone de' Medici.[21] The couple were married on 12 February 1736.[22]

The Duchess of Lorraine's love for her husband was strong and possessive.[23] The letters she sent to him shortly before their marriage expressed her eagerness to see him; his letters, on the other hand, were stereotyped and formal.[24][25] She was very jealous of her husband and his infidelity was the greatest problem of their marriage,[26] with Maria Wilhelmina, Princess of Auersperg, as his best-known mistress.[27]

Upon Gian Gastone's death on 9 July 1737, Francis Stephen ceded Lorraine and became Grand Duke of Tuscany. In 1738, Charles VI sent the young couple to make their formal entry into Tuscany. A triumphal arch was erected at the Porta Galla in celebration, where it remains today. Their stay in Florence was brief. Charles VI soon recalled them, as he feared he might die while his heiress was miles away in Tuscany.[28] In the summer of 1738, Austria suffered defeats during the ongoing Russo-Turkish War. The Turks reversed Austrian gains in Serbia, Wallachia and Bosnia. The Viennese rioted at the cost of the war. Francis Stephen was popularly despised, as he was thought to be a cowardly French spy.[29] The war was concluded the next year with the Treaty of Belgrade.

Ascension

Maria Theresa's procession through the Graben, 22 November 1740. The pregnant queen is on way to hear High Mass at St. Stephen's Cathedral before receiving homage.[30]

Charles VI died on 20 October 1740, probably of mushroom poisoning. He had ignored the advice of Prince Eugene of Savoy who had urged him to concentrate on filling the treasury and equipping the army rather than on acquiring signatures of fellow monarchs.[5] The Emperor, who spent his entire reign securing the Pragmatic Sanction, left Austria in an impoverished state, bankrupted by the recent Turkish war and the War of the Polish Succession;[31] the treasury contained only 100,000 gulden, which were claimed by his widow.[32] The army had also been weakened due to these wars; instead of the full number of 160,000, the army had been reduced to about 108,000, and they were scattered in small areas from the Austrian Netherlands to Transylvania, and from Silesia to Tuscany. They were also poorly trained and discipline was lacking. Later Maria Theresa even made a remark: "as for the state in which I found the army, I cannot begin to describe it."[33]

Maria Theresa found herself in a difficult situation. She did not know enough about matters of state and she was unaware of the weakness of her father's ministers. She decided to rely on her father's advice to retain his counselors and to defer to her husband, whom she considered to be more experienced, on other matters. Both decisions later gave cause for regret. Ten years later, Maria Theresa recalled in her Political Testament the circumstances under which she had ascended: "I found myself without money, without credit, without army, without experience and knowledge of my own and finally, also without any counsel because each one of them at first wanted to wait and see how things would develop."[14]

She dismissed the possibility that other countries might try to seize her territories and immediately started ensuring the imperial dignity for herself;[14] since a woman could not be elected Holy Roman Empress, Maria Theresa wanted to secure the imperial office for her husband, but Francis Stephen did not possess enough land or rank within the Holy Roman Empire.[note 4] In order to make him eligible for the imperial throne and to enable him to vote in the imperial elections as elector of Bohemia (which she could not do because of her sex), Maria Theresa made Francis Stephen co-ruler of the Austrian and Bohemian lands on 21 November 1740.[34] It took more than a year for the Diet of Hungary to accept Francis Stephen as co-ruler, since they asserted that the sovereignty of Hungary could not be shared.[35] Despite her love for him and his position as co-ruler, Maria Theresa never allowed her husband to decide matters of state and often dismissed him from council meetings when they disagreed.[36]

The first display of the new queen's authority was the formal act of homage of the Lower Austrian Estates to her on 22 November 1740. It was an elaborate public event which served as a formal recognition and legitimation of her accession. The oath of fealty to Maria Theresa was taken on the same day in the Ritterstube of the Hofburg.[30]

War of the Austrian Succession

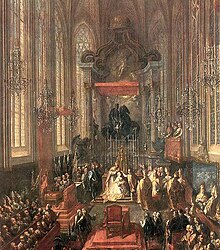

Maria Theresa being crowned Queen of Hungary, St. Martin's Cathedral, Pressburg

Maria Theresa as the Queen of Hungary

Immediately after her accession, a number of European sovereigns who had recognised Maria Theresa as heir broke their promises. Queen Elisabeth of Spain and Elector Charles Albert of Bavaria, married to Maria Theresa's deprived cousin Maria Amalia and supported by Empress Wilhelmine Amalia, coveted portions of her inheritance.[32] Maria Theresa did secure recognition from King Charles Emmanuel III of Sardinia, who had not accepted the Pragmatic Sanction during her father's lifetime, in November 1740.[37]

In December, Frederick II of Prussia invaded the Duchy of Silesia and requested that Maria Theresa cede it, threatening to join her enemies if she refused. Maria Theresa decided to fight for the mineral-rich province.[38] Frederick even offered a compromise: he would defend Maria Theresa's rights if she agreed to cede to him at least a part of Silesia. Francis Stephen was inclined to consider such an arrangement, but the Queen and her advisers were not, fearing that any violation of the Pragmatic Sanction would invalidate the entire document.[39] Maria Theresa's firmness soon assured Francis Stephen that they should fight for Silesia,[note 5] and she was confident that she would retain "the jewel of the House of Austria".[40] The resulting war with Prussia is known as the First Silesian War. The invasion of Silesia by Frederick was the start of a lifelong enmity; she referred to him as "that evil man".1982

As Austria was short of experienced military commanders, Maria Theresa released Marshall Neipperg, who had been imprisoned by her father for his poor performance in the Turkish War.[41] Neipperg took command of the Austrian troops in March. The Austrians suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Mollwitz in April 1741.[42] France drew up a plan to partition Austria between Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony and Spain: Bohemia and Upper Austria would be ceded to Bavaria, and the Elector would become Emperor, whereas Moravia and Upper Silesia would be granted to the Electorate of Saxony, Lower Silesia and Glatz to Prussia, and the entire Austrian Lombardy to Spain.[43]Marshall Belle-Isle joined Frederick at Olmütz. Vienna was in a panic, as none of Maria Theresa's advisors expected France to betray them. Francis Stephen urged Maria Theresa to reach a rapprochement with Prussia, as did Great Britain.[44] Maria Theresa reluctantly agreed to negotiations.[45]

Contrary to all expectations, a significant amount of support for the young Queen came from Hungary.[46] Her coronation as Queen of Hungary took place in St. Martin's Cathedral, Pressburg, on 25 June 1741. She had spent months honing the equestrian skills necessary for the ceremony and negotiating with the Diet. To appease those who considered her gender to be a serious obstacle, Maria Theresa assumed masculine titles. Thus, in nomenclature, Maria Theresa was archduke and king; normally, however, she was styled as queen.[47]

By July, attempts at conciliation had completely collapsed. Maria Theresa's ally, the Elector of Saxony, now became her enemy,[48] and George II declared the Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg to be neutral.[49] Therefore, she needed troops from Hungary in order to support the war effort. Although she had already won the admiration of the Hungarians, the number of volunteers were only in hundreds. Since she required them in thousands or even tens of thousands, she decided to appear before the Hungarian Diet on 11 September 1741 while wearing the crown of St Stephen. She began addressing the Diet in Latin, and she asserted that "the very existence of the Kingdom of Hungary, of our own person and children, and our crown, are at stake. Forsaken by all, we place our sole reliance in the fidelity and long-tried valor of the Hungarians."[50] The response was rather boorish, with the queen being questioned and even heckled by members of the Diet; someone cried that she "better apply to Satan than the Hungarians for help."[51] However, she managed to show her gift for theatrical displays by holding her son and heir, Joseph, while weeping, and she dramatically consigned the future king to the defense of the "brave Hungarians".[51] This act managed to win the sympathy of the members, and they declared that they would die for Maria Theresa.[51][52]

In 1741, the Austrian authorities informed Maria Theresa that the Bohemian populace would prefer Charles Albert to her as sovereign. Maria Theresa, desperate and burdened by pregnancy, wrote plaintively to her sister: "I don't know if a town will remain to me for my delivery."[53] She bitterly vowed to spare nothing and no one to defend her kingdom when she wrote to the Bohemian chancellor, Count Philip Kinsky: "My mind is made up. We must put everything at stake to save Bohemia."[54][note 6] On 26 October, the Elector of Bavaria captured Prague and declared himself King of Bohemia. Maria Theresa, then in Hungary, wept on learning of the loss of Bohemia.[55] Charles Albert was unanimously elected Holy Roman Emperor on 24 January 1742, which made him the only non-Habsburg to be in that position since 1440.[56] The Queen, who regarded the election as a catastrophe,[57] caught her enemies unprepared by insisting on a winter campaign;[58] the same day he was elected emperor, Austrian troops under Ludwig Andreas von Khevenhüller captured Munich, Charles Albert's capital.[59]

.mw-parser-output .quoteboxbackground-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleftmargin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatrightmargin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centeredmargin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright pfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .quotebox-titlebackground-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:beforefont-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:afterfont-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-alignedtext-align:left.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-alignedtext-align:right.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-alignedtext-align:center.mw-parser-output .quotebox citedisplay:block;font-style:normal@media screen and (max-width:360px).mw-parser-output .quoteboxmin-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important

Prussian ambassador's letter to Frederick the Great[note 7]

The Treaty of Breslau of June 1742 ended hostilities between Austria and Prussia. With the First Silesian War at an end, the Queen soon made the recovery of Bohemia her priority.[60] French troops fled Bohemia in the winter of the same year. On 12 May 1743, Maria Theresa had herself crowned Queen of Bohemia in St. Vitus Cathedral.[61]

Prussia became anxious at Austrian advances on the Rhine frontier, and Frederick again invaded Bohemia, beginning a Second Silesian War; Prussian troops sacked Prague in August 1744. The French plans fell apart when Charles Albert died in January 1745. The French overran the Austrian Netherlands in May.[62]

Francis Stephen was elected Holy Roman Emperor on 13 September 1745. Prussia recognised Francis as emperor, and Maria Theresa once again recognised the loss of Silesia by the Treaty of Dresden in December 1745, ending the Second Silesian War.[63] The wider war dragged on for another three years, with fighting in northern Italy and the Austrian Netherlands; however, the core Habsburg domains of Austria, Hungary and Bohemia remained in Maria Theresa's possession. The Treaty of Aachen, which concluded the eight-year conflict, recognised Prussia's possession of Silesia, and Maria Theresa ceded the Duchy of Parma to Philip of Spain.[64] France had successfully conquered the Austrian Netherlands, but Louis XV, wishing to prevent potential future wars with Austria, returned them to Maria Theresa.[65]

Seven Years' War

The battle of Kolin, 1757

Frederick of Prussia's invasion of Saxony in August 1756 began a Third Silesian War and sparked the wider Seven Years' War. Maria Theresa and Kaunitz wished to exit the war with possession of Silesia.[66] Before the war started, Kaunitz had been sent as an ambassador at Versailles from 1750-53 to win over the French. Meanwhile, the British still refused to help Maria Theresa in reclaiming Silesia, and Frederick II himself managed to secure the Treaty of Westminster (1756) with them. Subsequently, Maria Theresa sent Georg Adam, Prince of Starhemberg to negotiate an agreement with France, and the result was the First Treaty of Versailles of 1 May 1756. Thus, the efforts of Kaunitz and Starhemberg managed to pave a way for a Diplomatic Revolution; previously, France was one of Austria’s archenemies together with Russia and the Ottoman Empire, but after the agreement, they were united by a common cause to contain Frederick II and British colonial expansion. [67] However, historians had blamed this treaty for causing the loss of the French colonial empire, since Louis XV was required to deploy troops in Germany and to provide subsidies of 25-30 million pounds a year to Maria Theresa that were vital for the Austrian war effort in Bohemia and Silesia.[68]

On 1 May 1757, the Second Treaty of Versailles was signed, whereby Louis XV promised to provide Austria with 130,000 men in addition to 12 million gulden yearly. They would also continue the war in Continental Europe until Prussia could be compelled to abandon Silesia and Glatz. In return, Austria would cede several towns in the Austrian Netherlands to the son-in-law of Louis XV, Philip of Parma, who in turn would grant his Italian duchies to Maria Theresa.[68]

Maximilian von Browne commanded the Austrian troops. Following the indecisive Battle of Lobositz in 1756, he was replaced by Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine, Maria Theresa's brother-in-law.[69] However, he was appointed only because of his familial relations; he turned out to be an incompetent military leader, and he was later replaced by Leopold Joseph von Daun, Franz Moritz von Lacy and Ernst Gideon von Laudon.[70] Frederick himself was startled by Lobositz; he eventually re-grouped for another attack in June 1757. The Battle of Kolin that followed was a decisive victory for Austria. Frederick lost one third of his troops, and before the battle was over, he had left the scene.[71] Subsequently, Prussia was defeated at Hochkirch in Saxony on 14 October 1758, at Kunersdorf in Brandenburg on 12 August 1759, and at Landeshut near Glatz in June 1760. Hungarian and Croat light hussars led by Count Hadik raided Berlin in 1757. Austrian and Russian troops even occupied Berlin for several days in August 1760. However, these victories did not enable the Habsburgs to win the war, as the French and Habsburg armies were destroyed by Frederick at Rossbach in 1757.[70] After the defeat in Torgau on 3 November 1760, Maria Theresa realised that she could no longer reclaim Silesia. In the meantime, France was losing badly in America and India, and thus they had reduced their subsidies by 50%. Since 1761, Kaunitz had tried to organise a diplomatic congress to take advantage of the accession of George III of the United Kingdom, as he did not really care about Germany. Finally, the war was concluded by the Treaty of Hubertusburg and Paris in 1763. Austria had to leave the Prussian territories that were occupied.[70] Although Silesia remained under the control of Prussia, a new balance of power was created in Europe, and Austrian position was strengthened by it thanks to its alliance with the Bourbons in Madrid, Parma and Naples. Maria Theresa herself decided to focus on domestic reforms and refrain from undertaking any further military operations.[72]

Family life

Maria Theresa with her family, 1754, by Martin van Meytens

Over the course of twenty years, Maria Theresa gave birth to sixteen children, thirteen of whom survived infancy. The first child, Maria Elisabeth (1737–1740), was born a little less than a year after the wedding. The child's sex caused great disappointment and so would the births of Maria Anna, the eldest surviving child, and Maria Carolina (1740–1741). While fighting to preserve her inheritance, Maria Theresa gave birth to a son named after Saint Joseph, to whom she had repeatedly prayed for a male child during the pregnancy. Maria Theresa's favourite child, Maria Christina, was born on her 25th birthday, four days before the defeat of the Austrian army in Chotusitz. Five more children were born during the war: Maria Elisabeth, Charles, Maria Amalia, Leopold and Maria Carolina (1748–1748). During this period, there was no rest for Maria Theresa during pregnancies or around the births; the war and child-bearing were carried on simultaneously. Five children were born during the peace between the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years' War: Maria Johanna, Maria Josepha, Maria Carolina, Ferdinand and Maria Antonia. She delivered her last child, Maximilian Francis, during the Seven Years' War, aged 39.[73] Maria Theresa asserted that, had she not been almost always pregnant, she would have gone into battle herself.1982

Maria Theresa's mother, Empress Elisabeth Christine, died in 1750. Four years later, Maria Theresa's governess, Marie Karoline von Fuchs-Mollard, died. She showed her gratitude to Countess Fuchs by having her buried in the Imperial Crypt along with the members of the imperial family.[74]

Shortly after giving birth to the younger children, Maria Theresa was confronted with the task of marrying off the elder ones. She led the marriage negotiations along with the campaigns of her wars and the duties of state. She used them as pawns in dynastic games and sacrificed their happiness for the benefit of the state.[75] A devoted but self-conscious mother, she wrote to all of her children at least once a week and believed herself entitled to exercise authority over her children regardless of their age and rank.[76]

The dowager empress with family, 1776, by Heinrich Füger

Following her fiftieth birthday in May 1767, Maria Theresa contracted smallpox from her daughter-in-law, Maria Josepha of Bavaria.[77] She survived, but the new empress did not. Maria Theresa then forced her daughter, Archduchess Maria Josepha, to pray with her in the Imperial Crypt next to the unsealed tomb of Empress Maria Josepha. The Archduchess started showing smallpox rash two days after visiting the crypt and soon died. Maria Carolina was to replace her as the pre-determined bride of King Ferdinand IV of Naples. Maria Theresa blamed herself for her daughter's death for the rest of her life because, at the time, the concept of an extended incubation period was largely unknown and it was believed that Maria Josepha had caught smallpox from the body of the late empress.[note 8]

In April 1770, Maria Theresa's youngest daughter, Maria Antonia, married Louis, Dauphin of France, by proxy in Vienna. Maria Antonia's education was neglected, and when the French showed an interest in her, her mother went about educating her as best she could about the court of Versailles and the French. Maria Theresa kept up a fortnightly correspondence with Maria Antonia, now called Marie Antoinette, in which she often reproached her for laziness and frivolity and scolded her for failing to conceive a child.[76]

Maria Theresa was not just critical of Marie Antoinette. She disliked Leopold's reserve and often blamed him for being cold. She criticised Maria Carolina for her political activities, Ferdinand for his lack of organisation, and Maria Amalia for her poor French and haughtiness. The only child she did not constantly scold was Maria Christina, who enjoyed her mother's complete confidence, though she failed to please her mother in one aspect – she did not produce any surviving children.[76]

One of Maria Theresa's greatest wishes was to have as many grandchildren as possible, but she had only about two dozen at the time of her death, of which all the eldest surviving daughters were named after her, with the exception of Caroline of Parma, her eldest granddaughter by Maria Amalia.[76][note 9]

Religious views and policies

Maria Theresa and her family celebrating Saint Nicholas, by Archduchess Maria Christina, in 1762.

Like all members of the House of Habsburg, Maria Theresa was a Roman Catholic, and a devout one. She believed that religious unity was necessary for a peaceful public life and explicitly rejected the idea of religious toleration. She even advocated for a state church.[note 10] and contemporary adversary travelers criticised her regime as bigoted, intolerant and superstitious.[78] However, she never allowed the Church to interfere with what she considered to be prerogatives of a monarch and kept Rome at arm's length. She controlled the selection of archbishops, bishops and abbots.[79] Overall, the ecclesiastical policies of Maria Theresa were enacted to ensure the primacy of State control in Church-State relations.[80] She was also influenced by Jansenist ideas. One of the most important aspects of Jansenism was the advocation of maximum freedom of national churches from Rome. Although Austria had always stressed the rights of the state in relation to the church, Jansenism provided new theoretical justification for this.1982

Maria Theresa promoted the Greek Catholics and emphasised their equal status with Roman Catholics.[81] Despite the fact that Maria Theresa was a very pious person, she also enacted policies that suppressed exaggerated display of piety, such as the prohibition of public flagellantism. Furthermore, she significantly reduced the number of religious holidays and monastic orders.1982

Jesuits

Her relationship with the Jesuits was complex. Members of this order educated her, served as her confessors, and supervised the religious education of her eldest son. The Jesuits were powerful and influential in the early years of Maria Theresa's reign. However, the queen's ministers convinced her that the order posed a danger to her monarchical authority. Not without much hesitation and regret, she issued a decree that removed them from all the institutions of the monarchy, and carried it out thoroughly. She forbade the publication of Pope Clement XIII's bull, which was in favour of the Jesuits, and promptly confiscated their property when Pope Clement XIV suppressed the order.[82]

Jews and Protestants

Joseph, Maria Theresa's eldest son and co-ruler, in 1775, by Anton von Maron

Though she eventually gave up trying to convert her non-Catholic subjects to Catholicism, Maria Theresa regarded both the Jews and Protestants as dangerous to the state and actively tried to suppress them.[83] She was probably the most anti-Jewish monarch of her time, having inherited the traditional prejudices of her ancestors and acquired new ones. This was a product of deep religious devotion and was not kept secret in her time. In 1777, she wrote of the Jews: "I know of no greater plague than this race, which on account of its deceit, usury and avarice is driving my subjects into beggary. Therefore as far as possible, the Jews are to be kept away and avoided."[84] Her hatred was so deep that she was willing to tolerate Protestant businessmen and financiers in Vienna, such as the Swiss-born Johann Fries, since she wanted to break free from the Jewish financiers.[85]

In December 1744, she proposed to her ministers the expulsion of Jews from Austria and Bohemia. Her first intention was to deport all Jews by 1 January, but having accepted the advice of her ministers, who were concerned by the number of future deportees that could reach 50,000, had the deadline slipped to June.[86] The expulsion orders were only retracted in 1748 due to pressures from other countries, including Great Britain.[85] She also ordered the deportation of around 20,000 Jews from Prague amid accusations that they were disloyal at the time of the Bavarian-French occupation during the War of the Austrian Succession. The order was then expanded to all Jews of Bohemia and major cities of Moravia, although the order was later backtracked except for Prague Jews that had already been expelled.[87] In addition to this, she exiled Protestants from Austria to Transylvania, including 2,600 from Upper Austria in the 1750s.[85] Despite this, practical, demographical and economic considerations prevented her from expelling the Protestants en masse. In 1777, she abandoned the idea of expelling Moravian Protestants after Joseph, who was opposed to her intentions, threatened to abdicate as emperor and co-ruler. Finally, she was forced to grant them some toleration by allowing them to worship privately.[88] Joseph himself regarded his mother's religious policies as "unjust, impious, impossible, harmful and ridiculous".[83]

In the third decade of her reign, influenced by her Jewish courtier Abraham Mendel Theben, Maria Theresa issued edicts that offered some state protection to her Jewish subjects. Her actions during the late stages of her reign contrast her early opinions. She forbade the forcible conversion of Jewish children to Christianity in 1762, and in 1763 she forbade Catholic clergy from extracting surplice fees from her Jewish subjects. In 1764, she ordered the release of those Jews who had been jailed for a blood libel in the village of Orkuta.[89] Notwithstanding her strong dislike of Jews, Maria Theresa supported Jewish commercial and industrial activity in Austria.[90] There were also parts of the realm where the Jews were treated better, such as Trieste, Gorizia and Vorarlberg.[88]

Reforms

Maria Theresa in 1762, by Jean-Étienne Liotard

Institutional

Maria Theresa was as conservative in matters of state as in those of religion, but implemented significant reforms to strengthen Austria's military and bureaucratic efficiency.[91] She employed Count Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz, who modernised the empire by creating a standing army of 108,000 men, paid for with 14 million gulden extracted from each crown-land. The central government was responsible for the army, although Haugwitz instituted taxation of the nobility, who never before had to pay taxes.[92] Moreover, after Haugwitz was appointed as the head of the new central administrative agency dubbed the Directory (Directorium in publicis et cameralibus) in 1749, he initiated a radical centralization of state institutions down to the level of the District Office (Kreisamt).[93] Thanks to this effort, by 1760 there was a class of government officials numbering around 10,000. However, Lombardy, the Austrian Netherlands and Hungary were almost completely untouched by this reform.[93] In case of Hungary, she was particularly mindful of her promise that she would respect the privileges in the kingdom, including the immunity of nobles from taxation.[94]

In light of the failure to reclaim Silesia during the Seven Years War, the governing system was once agained reformed to strengthen the state.[95] The Directory was transformed into the United Austrian and Bohemian Chancellery in 1761 that was equipped with a separate, independent judiciary and separate financial bodies.[95] She also refounded the Hofkamer in 1762, which was a ministry of finances that controlled all revenues from the monarchy. In addition to this, there was the Hofrechenskammer or the exchequer which was tasked with the handling of all financial accounts.[96] Meanwhile, in 1760, Maria Theresa created the Council of State (Staatsrat), composed of the state chancellor, three members of the high nobility and three knights, which served as a committee of experienced people who advised her. The council of state lacked executive or legislative authority, but nevertheless showed the difference between the form of government employed by Frederick II of Prussia. Unlike the latter, Maria Theresa was not an autocrat who acted as her own minister. Prussia would adopt this form of government only after 1807.1982

Maria Theresa doubled the state revenue from 20 to 40 million gulden between 1754 and 1764, though her attempt to tax clergy and nobility was only partially successful.[91][97] These financial reforms greatly improved the economy.[98] After Kaunitz became the head of the new Staatsrat, he pursued a policy of "aristocratic Enlightenment" that relied on persuasion to interact with the estates, and he was also willing to retract some of Haugwitz's centralization to curry favour with them. Nonetheless, the governing system remained centralised, and a strong institution made it possible for Kaunitz to increase state revenues substantially. In 1775, for the first time ever the Habsburg Monarchy achieved its first balanced budget, and by 1780, the Habsburg state revenue had reached 50 million gulden.[99]

Medicine

After Maria Theresa recruited Gerard van Swieten from the Netherlands, he also employed a fellow Dutchman named Anton de Haen, and de Haen was the actual founder of the Viennese Medicine School (Wiener Medizinischen Schule).[100] Maria Theresa also banned the creation of new burial grounds without prior government permission, thus countering wasteful and unhygienic burial customs.[101] Meanwhile, her decision to have her children inoculated after the smallpox epidemic of 1767 was responsible for changing Austrian physicians' negative view of inoculation. Maria Theresa herself inaugurated inoculation in Austria by hosting a dinner for the first sixty-five inoculated children in Schönbrunn Palace, waiting on the children herself.[102] In 1770, she enacted a strict regulation of the sale of poisons, and apothecaries were obliged to keep a poison register recording the quantity and circumstances of every sale. If someone unknown tried to purchase a poison, that person had to provide two character witnesses before a sale could be effectuated. Three years later, she prohibited the use of lead in any eating or drinking vessels; the only permitted material for this purpose was pure tin.[103]

Law

Prussian ambassador's letter to Frederick II of Prussia[104]

The centralization of the Habsburg government necessitated the creation of a unified legal system. Previously, various lands in the Habsburg realm had their own laws. These laws were compiled and the resulting Codex Theresianus could be used as a basis for legal unification.[105] In 1769, the Constitutio Criminalis Theresiana was published, and this was a codification of the traditional criminal justice system since the Middle Ages. This criminal code allowed the possibility of establishing the truth through torture, and it also criminalised witchcraft and various religious offenses. Although this law came into force in Austria and Bohemia, it was not valid in Hungary.[106]

She was particularly concerned with the sexual morality of her subjects. Thus, she established a Chastity Commission (Keuschheitskommission) in 1752[107] to clamp down on prostitution, homosexuality, adultery and even sex between members of different religions.[108] This Commission cooperated closely with the police, and the Commission even employed secret agents to investigate private lives of men and women with bad reputation.[109] They were authorised to raid banquets, clubs, and private gatherings, and to arrest those suspected of violating social norms.[110] The punishments included whipping, deportation, or even the death penalty.[108]

In 1776, Austria outlawed torture, particularly at the behest of Joseph II. Much unlike Joseph, but with the support of religious authorities, Maria Theresa was opposed to the abolition of torture. Born and raised between Baroque and Rococo eras, she found it difficult to fit into the intellectual sphere of the Enlightenment, which is why she only slowly followed humanitarian reforms on the continent.[111]

From an institutional perspective, in 1749, she founded the Supreme Judiciary as a court of final appeal for all hereditary lands.[96]

Education

Austrian historian Karl Vocelka observed that the educational reforms enacted by Maria Theresa were "really founded on Enlightenment ideas," although the ulterior motive was still to "meet the needs of an absolutist state, as an increasingly sophisticated and complicated society and economy required new administrators, officers, diplomats and specialists in virtually every area."[112] Previously, the existing primary schools were run by various orders of the Catholic Church. After her reform, compulsory and secular primary schools were established.[112] Maria Theresa herself might have wanted the schools to teach Catholic orthodoxy, but the curriculum focused on social responsibility, social discipline, work ethic and the use of reason rather than mere rote learning.[113] All children of both genders from the ages of six to twelve were required to attend school.[114] The education reform was met with hostility particularly by peasants who wanted the children to work in the fields instead.[113] Maria Theresa crushed the dissent by ordering the arrest of all those opposed.[114] Overall, although the idea had merit, the reforms were not as successful as they were expected to be; in some parts of Austria, half of the population was illiterate well into the 19th century.[112]

Maria Theresa permitted non-Catholics to attend university and allowed the introduction of secular subjects (such as law), which influenced the decline of theology as the main foundation of university education.[91] Furthermore, under her reign, educational institutions were created to prepare officials for work in the state bureaucracy, the Theresianum was established in Vienna in 1746 to educate nobles' sons, a military school named the Theresian Military Academy was founded in Wiener Neustadt in 1751, and an Oriental Academy for future diplomats was created in 1754.[115]

Censorship

Her regime was also known for institutionalising censorship of publications and learning. English author Sir Nathaniel Wraxall once wrote from Vienna: "[T]he injudicious bigotry of the Empress may chiefly be attributed the deficiency [in learning]. It is hardly credible how many books and productions of every species, and in every language, are proscribed by her. Not only Voltaire and Rousseau are included in the list, from the immoral tendency or licentious nature of their writings; but many authors whom we consider as unexceptionable or harmless, experience a similar treatment."[116] The censorship particularly affected works that were deemed to be against the Catholic religion. Ironically, for this purpose, she was aided by Gerard van Swieten who was considered to be an "enlightened" man.[116]

Economy

Maria Theresa endeavoured to increase the living standards of the people, since she could see a causal link between peasant living standards, productivity and state revenue.[117] The Habsburg government under her rule also tried to strengthen its industry through government interventions. After the loss of Silesia, they implemented subsidies and trade barriers to encourage the move of Silesian textile industry to northern Bohemia. In addition, they cut back guild privileges, and internal duties on trade were either reformed or removed (such as the case for the Austrian-Bohemian lands in 1775).[113] Another economic issue that had to be tackled during the reign of Maria Theresa was the regulation of noble privileges vis-à-vis peasant well-being. Although Maria Theresa was initially reluctant to meddle in such affairs, government interventions were made possible by the perceived need for economic power and the emergence of a functioning bureaucracy, and interventions were also further eased by widespread peasant unrest induced by the effects of war and famine in 1770-2 and noble abuse of manorial rights.[118] In 1771-78, a series of "Robot Patents" were issued by Maria Theresa, and these patents regulated and restricted peasant labour only in the German and Bohemian parts of the realm. The goal was to ensure that peasants not only could support themselves and their family members, but also help cover the national expenditure in peace or war. However, such reform was fiercely resisted by the Hungarian nobility. Meanwhile, Joseph was hoping for a more radical change, and he himself abolished forced peasant labour during his reign in 1789, although this was later retracted by Emperor Leopold II.[119]

Late reign

Maria Theresa as a widow in 1773, by Anton von Maron. Peace holds the olive crown above her head, reaffirming Maria Theresa's monarchical status. This was the last commissioned state portrait of Maria Theresa.[120]

Emperor Francis died on 18 August 1765, while he and the court were in Innsbruck celebrating the wedding of his second son, Leopold. Maria Theresa was devastated. Their eldest son, Joseph, became Holy Roman Emperor. Maria Theresa abandoned all ornamentation, had her hair cut short, painted her rooms black and dressed in mourning for the rest of her life. She completely withdrew from court life, public events, and theater. Throughout her widowhood, she spent the whole of August and the eighteenth of each month alone in her chamber, which negatively affected her mental health.[121] She described her state of mind shortly after Francis's death: "I hardly know myself now, for I have become like an animal with no true life or reasoning power."[122]

Upon his accession to the imperial throne, Joseph ruled less land than his father had in 1740. Believing that the emperor must possess enough land to maintain the Empire's integrity, Maria Theresa, who was used to being assisted in the administration of her vast realms, declared Joseph to be her new co-ruler on 17 September 1765.[123] From then on, mother and son had frequent ideological disagreements. The 22 million gulden that Joseph inherited from his father was injected into the treasury. Maria Theresa had another loss in February 1766 when Haugwitz died. She gave her son absolute control over the military following the death of Count Leopold Joseph von Daun.[124]

According to Robert A. Kann, Maria Theresa was a monarch of above-average qualifications but intellectually inferior to Joseph and Leopold. Kann asserts that she nevertheless possessed qualities appreciated in a monarch: warm heart, practical mind, firm determination and sound perception. Most importantly, she was ready to recognise the mental superiority of some of her advisers and to give way to a superior mind while enjoying support of her ministers even if their ideas differed from her own. Joseph, however, was never able to establish rapport with the same advisers, even though their philosophy of government was closer to Joseph's than to Maria Theresa's.[125]

The relationship between Maria Theresa and Joseph was not without warmth but was complicated and their personalities clashed. Despite his intellect, Maria Theresa's force of personality often made Joseph cower.[126] Sometimes, she openly admired his talents and achievements, but she was also not hesitant to rebuke him. She even wrote: "We never see each other except at dinner ... His temper gets worse every day ... Please burn this letter ... I just try to avoid public scandal."[127] In another letter, also addressed to Joseph's companion, she complained: "He avoids me ... I am the only person in his way and so I am an obstruction and a burden ... Abdication alone can remedy matters."[127] After much contemplation, she chose not to abdicate. Joseph himself often threatened to resign as co-regent and emperor, but he, too, was induced not to do so. Her threats of abdication were rarely taken seriously; Maria Theresa believed that her recovery from smallpox in 1767 was a sign that God wished her to reign until death. It was in Joseph's interest that she remained sovereign, for he often blamed her for his failures and thus avoided taking on the responsibilities of a monarch.[128]

Joseph and Prince Kaunitz arranged the First Partition of Poland despite Maria Theresa's protestations. Her sense of justice pushed her to reject the idea of partition, which would hurt the Polish people.[129] She even once argued, "What right have we to rob an innocent nation that it has hitherto been our boast to protect and support?"[130] The duo argued that it was too late to abort now. Besides, Maria Theresa herself agreed with the partition when she realised that Frederick II of Prussia and Catherine II of Russia would do it with or without Austrian participation. Maria Theresa claimed and eventually took Galicia and Lodomeria; in the words of Frederick, "the more she cried, the more she took".[131]

A few years after the partition, Russia defeated the Ottoman Empire in the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774). Following the signing of the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774 that concluded the war, Austria entered into negotiations with the Sublime Porte. Thus, in 1775, the Ottoman Empire ceded the northwestern part of Moldavia (subsequently known as Bukovina) to Austria.[132] Subsequently, on 30 December 1777, Maximilian III Joseph, Elector of Bavaria died without leaving any children.[131] As a result, his territories were coveted by ambitious men, including Joseph, who tried to swap Bavaria for the Austrian Netherlands.[133] This alarmed Frederick II of Prussia, and thus the War of Bavarian Succession erupted in 1778. Maria Theresa very unwilingly consented to the occupation of Bavaria, and a year later she made peace proposals to Frederick II despite Joseph's objections.[134] Although Austria managed to gain the Innviertel area, this "Potato War" caused a setback to the financial improvement that the Habsburg had made.[133] The 500,000 gulden in annual revenue from 100,000 inhabitants of Innviertel were not comparable to the 100,000,000 gulden that were spent during the war.[134]

Death and legacy

Maria Theresa and her husband are interred in the double tomb which she had inscribed as a widow.

It is unlikely that Maria Theresa ever completely recovered from the smallpox attack in 1767, as 18th-century writers asserted. She suffered from shortness of breath, fatigue, cough, distress, necrophobia and insomnia. She later developed edema.[135]

Maria Theresa fell ill on 24 November 1780. Her physician Dr. Störk thought her condition serious, although Joseph was confident that she would recover in no time. By 26 November, she asked for the last rites, and on 28 November, the doctor told her that the time had come. On 29 November, she died surrounded by her remaining children.[136][137] Her longtime rival Frederick II of Prussia, on hearing of her death, said that she had honored her throne and her sex, and though he had fought against her in three wars, he never considered her his enemy.[138] With her death, the House of Habsburg died out and was replaced by the House of Habsburg-Lorraine. Joseph, already co-sovereign of the Habsburg dominions, succeeded her, and he introduced sweeping reforms in the empire; Joseph II produced nearly 700 edicts per year (or almost two per day), whereas Maria Theresa only issued about 100 edicts per year.[139]

Maria Theresa understood the importance of her public persona and was able to simultaneously evoke both esteem and affection from her subjects; a notable example was how she projected dignity and simplicity to awe the people in Pressburg before she was crowned as the Queen of Hungary.[140] Her 40-year reign was considered to be very successful when compared to other Habsburg rulers. Her reforms had transformed the empire into a modern state with a significant international standing.[141] She centralised and modernised the institutions, and her reign was considered as the beginning of the era of "enlightened absolutism" in Austria, with a brand new approach towards governing: the measures undertaken by rulers became more modern and rational, and thoughts were given to the welfare of the state and the people.[142] However, it should be noted that many of her policies were not in line with the ideals of the Enlightenment (such as her support of torture), and she was still very much influenced by Catholicism from the previous era.[143] Vocelka even stated that "taken as a whole the reforms of Maria Theresa appear more absolutist and centralist than enlightened, even if one must admit that the influence of enlightened ideas is visible to a certain degree."[144]

Her body is buried in the Imperial Crypt in Vienna next to her husband in a coffin she had inscribed during her lifetime.[145]

Full title

Her title after the death of her husband was:

Maria Theresa, by the Grace of God, Dowager Empress of the Romans, Queen of Hungary, of Bohemia, of Dalmatia, of Croatia, of Slavonia, of Galicia, of Lodomeria, etc.; Archduchess of Austria; Duchess of Burgundy, of Styria, of Carinthia and of Carniola; Grand Princess of Transylvania; Margravine of Moravia; Duchess of Brabant, of Limburg, of Luxemburg, of Guelders, of Württemberg, of Upper and Lower Silesia, of Milan, of Mantua, of Parma, of Piacenza, of Guastalla, of Auschwitz and of Zator; Princess of Swabia; Princely Countess of Habsburg, of Flanders, of Tyrol, of Hainault, of Kyburg, of Gorizia and of Gradisca; Margravine of Burgau, of Upper and Lower Lusatia; Countess of Namur; Lady of the Wendish Mark and of Mechlin; Dowager Duchess of Lorraine and Bar, Dowager Grand Duchess of Tuscany.[146][note 11]

Coat of arms of Maria Theresa

Coat of arms of Maria Theresa as "king" of Hungary, 1777[note 12]

See also

- Maria-Theresien-Platz

- SMS Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia

- Military Order of Maria Theresa

- Maria Theresa thaler

- 295 Theresia

- Terezin

- Kings of Bohemia family tree

- Kings of Hungary family tree

- List of people with the most children

Notes

^ Members of the Habsburg dynasty often married their close relatives; examples of such inbreeding were uncle-niece pairs (Maria Theresa's grandfather Leopold and Margaret Theresa of Spain, Philip II of Spain and Anna of Austria, Philip IV of Spain and Mariana of Austria, etc). Maria Theresa, however, descended from Leopold I's third wife who was not closely related to him, and her parents were only distantly related. Beales 1987, pp. 20-21.

^ Rather than using the formal manner and speech, Maria Theresa spoke (and sometimes wrote) Viennese German, which she picked up from her servants and laidies-in-waiting. Spielman 1993, pp. 206.

^ Maria Theresa's father compelled Francis Stephen to renounce his rights to Lorraine and told him: "No renunciation, no archduchess." Beales 1987, pp. 23.

^ Francis Stephen was at the time Grand Duke of Tuscany, but Tuscany had not been part of the Holy Roman Empire since the Peace of Westphalia. His only possessions within the Empire were the Duchy of Teschen and County of Falkenstein. Beales 2005, pp. 190.

^ The day after the entrance of Prussia into Silesia, Francis Stephen exclaimed to the Prussian envoy, Major General Borcke: "Better the Turks before Vienna, better the surrender of the Netherlands to France, better every concession to Bavaria and Saxony, than the renunciation of Silesia!" Browning 1994, pp. 43.

^ She explained her resolution to the Count furthermore: "I shall have all my armies, all my Hungarians killed off before I cede so much as an inch of ground." Browning 1994, pp. 76.

^ At the end of the War of the Austrian Succession, Count Podewils was sent as an ambassador to the Austrian court by King Frederick II of Prussia. Podewils wrote detailed descriptions of Maria Theresa's physical appearance and how she spent her days. Mahan 1932, pp. 230.

^ It takes at least a week for the smallpox rash to appear after a person is infected. Since the rash appeared two days after Maria Josepha had visited the vault, the Archduchess must have been infected much before visiting the vault. Hopkins 2002, pp. 64.

^ The eldest surviving daughters of Maria Theresa's children were Maria Theresa of Austria (by Joseph), Maria Theresa of Tuscany (by Leopold), Maria Theresa of Naples and Sicily (by Maria Carolina), Maria Theresa of Austria-Este (by Ferdinand) and Marie Thérèse of France (by Marie Antoinette).

^ In a letter to Joseph, she wrote: "What, without a dominant religion? Toleration, indifferentism, are exactly the right means to undermine everything... What other restraint exists? None. Neither the gallows nor the wheel... I speak politically now, not as a Christian. Nothing is so necessary and beneficial as religion. Would you allow everyone to act according to his fantasy? If there were no fixed cult, no subjection to the Church, where should we be? The law of might would take command." Crankshaw 1970, pp. 302

^ In German: Maria Theresia von Gottes Gnaden Heilige Römische Kaiserinwitwe, Königin zu Ungarn, Böhmen, Dalmatien, Kroatien, Slavonien, Gallizien, Lodomerien, usw., Erzherzogin zu Österreich, Herzogin zu Burgund, zu Steyer, zu Kärnten und zu Crain, Großfürstin zu Siebenbürgen, Markgräfin zu Mähren, Herzogin zu Braband, zu Limburg, zu Luxemburg und zu Geldern, zu Württemberg, zu Ober- und Nieder-Schlesien, zu Milan, zu Mantua, zu Parma, zu Piacenza, zu Guastala, zu Auschwitz und Zator, Fürstin zu Schwaben, gefürstete Gräfin zu Habsburg, zu Flandern, zu Tirol, zu Hennegau, zu Kyburg, zu Görz und zu Gradisca, Markgräfin des Heiligen Römischen Reiches, zu Burgau, zu Ober- und Nieder-Lausitz, Gräfin zu Namur, Frau auf der Windischen Mark und zu Mecheln, Herzoginwitwe zu Lothringen und Baar, Großherzoginwitwe zu Toskana

^ On the middle shield Kingdom of Hungary, on the back shield "king" of Croatia, Dalmatia, Slavonia, Lodomeria, Galicia, Bosnia, Serbia, Cumania and Bulgaria

References

^ Goldsmith 1936, pp. 17.

^ Morris 1937, pp. 21.

^ ab Mahan 1932, pp. 6.

^ ab Mahan 1932, pp. 12.

^ ab Ingrao 2000, pp. 129.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 24.

^ "Pragmatic Sanction of Emperor Charles VI". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 November 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Ingrao 2000, pp. 128.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 23.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 228.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 19-21.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 21-2.

^ Morris 1937, pp. 28.

^ abc Browning 1994, pp. 37.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 24-5.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 22.

^ ab Mahan 1932, pp. 27.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 26.

^ Morris 1937, pp. 25-6.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 37.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 25.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 38.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 261.

^ Goldsmith 1936, pp. 55.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 39.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 261-2.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 262-3.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 26.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 25-6.

^ ab Spielman 1993, pp. 207.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 3.

^ ab Morris 1937, pp. 47.

^ Duffy 1977, pp. 145-6.

^ Beales 2005, pp. 182-3.

^ Beales 2005, pp. 189.

^ Roider 1973, pp. 8.

^ Browning 1994, pp. 38.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 43.

^ Browning 1994, pp. 43.

^ Browning 1994, pp. 42, 44.

^ Browning 1994, pp. 44.

^ Browning 1994, pp. 52-3.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 56.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 57.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 58.

^ Browning 1994, pp. 66.

^ Yonan 2003, pp. 118.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 75.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 77.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 121.

^ abc Mahan 1932, pp. 122.

^ Morris 1937, pp. 74.

^ Browning 1994, pp. 65.

^ Duffy 1977, pp. 151.

^ Browning 1994, pp. 79.

^ Beller 2006, pp. 86.

^ Browning 1994, pp. 88.

^ Browning 1994, pp. 92.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 93.

^ Browning 1994, pp. 114.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 96-7.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 97.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 99.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 99-100.

^ Mitford 1970, pp. 158.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 238.

^ Berenger 2014, pp. 80-2.

^ ab Berenger 2014, pp. 82.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 240.

^ abc Berenger 2014, pp. 83.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 242.

^ Berenger 2014, pp. 84.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 266–271, 313.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 22.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 271.

^ abcd Beales 1987, pp. 194.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 273.

^ Beales 2005, pp. 69.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 251.

^ Kann 1980, pp. 187.

^ Himka 1999, pp. 5.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 253.

^ ab Beales 2005, pp. 14.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 313.

^ abc Beller 2006, pp. 87.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 254.

^ Kann 1980, pp. 189-90.

^ ab Vocelka 2000, pp. 201.

^ Patai 1996, pp. 203.

^ Penslar 2001, pp. 32–33.

^ abc Byrne 1997, pp. 38.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 192.

^ ab Beller 2006, pp. 88.

^ Berenger 2014, pp. 86.

^ ab Beller 2006, pp. 89.

^ ab Berenger 2014, pp. 85.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 195.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 196.

^ Beller 2006, pp. 90.

^ Vocelka 2009, pp. 160.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 310.

^ Hopkins 2002, pp. 64–5.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 309.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 230.

^ Vocelka 2009, pp. 157-158.

^ Vocelka 2009, pp. 158.

^ Brandstätter 1986, pp. 163.

^ ab Krämer, Klaus (15 March 2017). "What made Austria's Maria Theresa a one-of-a-kind ruler". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

^ Goldsmith 1936, pp. 167-8.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 242.

^ Kann 1980, pp. 179.

^ abc Vocelka 2000, pp. 200.

^ abc Beller 2006, pp. 92.

^ ab Crankshaw 1970, pp. 308.

^ Beller 2006, pp. 91.

^ ab Goldsmith 1936, pp. 138.

^ Ingrao 2000, pp. 188.

^ Beller 2006, pp. 93.

^ "Robotpatent". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

^ Yonan 2003, pp. 116-7.

^ Yonan 2003, pp. 112.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 267.

^ Beales 2005, pp. 192.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 268, 271.

^ Kann 1980, pp. 157.

^ Beales 2005, pp. 182.

^ ab Beales 2005, pp. 183.

^ Beales 2005, pp. 185.

^ Ingrao 2000, pp. 194.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 285.

^ ab Ingrao 2000, pp. 195.

^ Vocelka 2009, pp. 154.

^ ab Beller 2006, pp. 94.

^ ab Ingrao 2000, pp. 196.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 334.

^ Crankshaw 1970, pp. 336–338.

^ Goldsmith 1936, pp. 272.

^ Mitford 1970, pp. 287.

^ Ingrao 2000, pp. 197.

^ Browning 1994, pp. 67.

^ Yonan 2011, pp. 3.

^ Vocelka 2009, pp. 154-155.

^ Vocelka 2009, pp. 156.

^ Vocelka 2000, pp. 202.

^ Mahan 1932, pp. 335.

^ Roider 1973, pp. 1.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

Beller, Steven (2006). A Concise History of Austria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47305-7.

Berenger, Jean (2014) [1997]. A History of the Habsburg Empire 1700–1918. Translated by Simpson, CA. New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-582-09007-1.

Brandstätter, Christian (1986). Stadt Chronik Wien: 2000 Jahre in Daten, Dokumenten und Bildern. Kremayr und Scheriau.

Browning, Reed (1994). The War of the Austrian Succession. Stroud: Alan Sutton. ISBN 0750905786.

Byrne, James M (1997). Religion and the Enlightenment: from Descartes to Kant. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-25760-7.

Crankshaw, Edward (1970). Maria Theresa. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0582107849.

Beales, Derek (1987). Joseph II: In the shadow of Maria Theresa, 1741–1780. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24240-1.

Beales, Derek (2005). Enlightenment and Reform in Eighteenth-Century Europe. London: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-950-5.

Duffy, Christopher (1977). The army of Maria Theresa: The Armed Forces of Imperial Austria, 1740–1780. London: David & Charles. ISBN 0715373870.

Goldsmith, Margaret (1936). Maria Theresa of Austria. London: Arthur Barker Ltd.

Himka, John-Paul (1999). Religion and nationality in Western Ukraine: the Greek Catholic Church and Ruthenian National Movement in Galicia, 1867–1900. Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 0-7735-1812-6.

Holborn, Hajo (1982). A History of Modern Germany: 1648–1840. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00796-9.

Hopkins, Donald R (2002). The greatest killer: smallpox in history, with a new introduction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-35168-8.

Ingrao, Charles W (2000). The Habsburg monarchy, 1618–1815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78505-7.

Kann, Robert (1980). A history of the Habsburg Empire, 1526–1918. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04206-9.

Yonan, Michael (2003). "Conceptualizing the Kaiserinwitwe: Empress Maria Theresa and Her Portraits". In Levy, Allison. Widowhood and Visual Culture in Early Modern Europe. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0-7546-0731-3.

Mahan, Jabez Alexander (1932). Maria Theresa of Austria. New York: Crowell.

Mitford, Nancy (1970). Frederick the Great. London: Hamish Hamilton.

Morris, Constance Lily (1937). Maria Theresa – The Last Conservative. New York, London: Alfred A. Knopf.

Patai, Raphael (1996). The Jews of Hungary: history, culture, psychology. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-2561-0.

Penslar, Derek Jonathan (2001). Shylock's children: economics and Jewish identity in modern Europe. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22590-2.

Roider, Karl (1973). Maria Theresa. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-556191-4.

Spielman, John Philip (1993). The city & the crown: Vienna and the imperial court, 1600–1740. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 1-55753-021-1.

Vocelka, Karl (2000). "Enlightenment in the Habsburg Monarchy: History of a Belated and Short-Lived Phenomenon". In Grell, Ole Peter; Porter, Roy. Toleration in Enlightenment Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521651964.

Vocelka, Karl (2009) [2000]. Geschichte Österreichs: Kultur, Gesellschaft, Politik (3rd ed.). München: Heyne Verlag. ISBN 3-453-21622-9.

Yonan, Michael (2011). Empress Maria Theresa and the Politics of Habsburg Imperial Art. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-03722-6.

External links

Media related to Maria Theresa of Austria at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Maria Theresa of Austria at Wikimedia Commons- Maria Theresa (Catholic Encyclopaedia)

- Maria Theresa, Archduchess of Austria

- Maria Theresa

- Maria Theresa, (1717–1780) Archduchess of Austria (1740–1780) Queen of Hungary and Bohemia (1740–1780)

Maria Theresa House of Habsburg Born: 13 May 1717 Died: 29 November 1780 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Emperor Charles VI | Queen of Bohemia 1740–1741 | Succeeded by Emperor Charles VII |

Duchess of Parma and Piacenza 1740–1748 | Succeeded by Philip of Spain | |

Queen of Hungary and Croatia Archduchess of Austria Duchess of Brabant, Limburg, Lothier, Luxembourg and Milan; Countess of Flanders, Hainaut and Namur 1740–1780 with Francis I (1740–1765) Joseph II (1765–1780) | Succeeded by Emperor Joseph II | |

| Preceded by Emperor Charles VII | Queen of Bohemia 1743–1780 with Francis I (1743–1765) Joseph II (1765–1780) | |

New title First Partition of Poland | Queen of Galicia and Lodomeria 1772–1780 | |

German royalty | ||

Vacant Title last held by Maria Amalia of Austria | Empress consort of the Holy Roman Empire 1745–1765 | Succeeded by Maria Josepha of Bavaria |

| Titles |

|---|