Humid continental climate

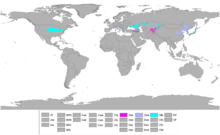

Humid continental climate worldwide, utilizing the Köppen climate classification

Dsa

Dsb

Dwa

Dwb

Dfa

Dfb

A humid continental climate (Köppen prefix D and a third letter of a or b) is a climatic region defined by Russo-German climatologist Wladimir Köppen in 1900,[1] typified by large seasonal temperature differences, with warm to hot (and often humid) summers and cold (sometimes severely cold in the northern areas) winters. Precipitation is usually distributed throughout the year. The definition of this climate regarding temperature is as follows: the mean temperature of the coldest month must be below −3 °C (26.6 °F) (or 0 °C (32.0 °F)) and there must be at least four months whose mean temperatures are at or above 10 °C (50 °F). In addition, the location in question must not be semi-arid or arid. The Dfb, Dwb and Dsb subtypes are also known as hemiboreal.

Humid continental climates are generally found roughly between latitudes 40° N and 60° N,[2] within the central and northeastern portions of North America, Europe, and Asia. They are much less commonly found in the Southern Hemisphere due to the larger ocean area at that latitude and the consequent greater maritime moderation. In the Northern Hemisphere some of the humid continental climates, typically in Scandinavia, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland are heavily maritime-influenced, with relatively cool summers and winters being just below the freezing mark.[3] More extreme humid continental climates found in northeast China, southern Siberia and the American Midwest combine hotter summer maxima and colder winters than the marine-based variety.[4]

Contents

1 Definition

1.1 Associated precipitation

1.2 Vegetation

2 Hot/warm summer subtype

3 Cool summer subtype

4 Use in climate modeling

5 See also

6 References

Definition

The snowy city of Sapporo, Japan, has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa).

Using the Köppen climate classification, a climate is classified as humid continental when the temperature of the coldest month is below −3 °C [26.6 °F] (or 0 °C [32.0 °F]) and there must be at least four months whose mean temperatures are at or above 10 °C (50 °F).[5] These temperatures were not arbitrary. In Europe, the −3 °C average temperature isotherm (line of equal temperature) was near the southern extent of winter snowpack. The 10 °C average temperature was found to be the minimum temperature necessary for tree growth.[6] Wide temperature ranges are common within this climate zone.[7]

Second letter in the classification symbol defines seasonal rainfall as follows:

s: A dry summer—the driest summer month has at most 30 millimetres (1.18 in) of rainfall and has at most 1⁄3 the precipitation of the wettest winter month,

w: A dry winter—the driest winter month has at most one‑tenth of the precipitation found in the wettest summer month,

f: Does not meet either of the alternative specifications.

while the third letter denotes the extent of summer heat:

a: Hot summer, warmest month averages above 22 °C (71.6 °F),

b: Cool summer, warmest month below 22 °

Associated precipitation

Within North America, moisture within this climate regime is supplied by the Gulf of Mexico and adjacent western subtropical Atlantic.[8]Precipitation is relatively well distributed year-round in many areas with this climate (f), while others may see a marked reduction in wintry precipitation,[6] which increases the chances of a wintertime drought (w).[9]Snowfall occurs in all areas with a humid continental climate and in many such places is more common than rain during the height of winter. In places with sufficient wintertime precipitation, the snow cover is often deep. Most summer rainfall occurs during thunderstorms,[6] and in North America and Asia an occasionally tropical system. Though humidity levels are often high in locations with humid continental climates, the "humid" designation means that the climate is not dry enough to be classified as semi-arid or arid.

Vegetation

Mixed forest in Vermont during autumn

By definition, forests thrive within this climate. Biomes within this climate regime include temperate woodlands, temperate grasslands, temperate deciduous, temperate evergreen forests,[8] and coniferous forests.[10] Within wetter areas, spruce, pine, fir, and oak can be found. Fall foliage is noted during the autumn.[6]

Hot/warm summer subtype

Regions with hot-summer humid continental climates

| Chicago[11] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A hot summer version of a continental climate features an average temperature of at least 22 °C (71.6 °F) in its warmest month.[12] Since these regimes are limited to the Northern Hemisphere, the warmest month is usually July or August. For example, Chicago has average July afternoon temperatures near 29 °C (84 °F), while average January afternoon temperature are near −1 °C (30.2 °F). Frost free periods normally last 4–5 months within this climate regime.[6]

Within North America, this climate includes small areas of central and southeast Canada, and portions of the central and eastern United States from the 100th meridian eastward to the Atlantic. Precipitation increases further eastward in this zone and is less seasonally uniform in the west. The western states of the central United States (namely Montana, Wyoming, parts of southern Idaho, most of Lincoln County in Eastern Washington, parts of Colorado, parts of Utah, western Nebraska, and parts of western North and South Dakota) have thermal regimes which fit the Dfa climate type, but are quite dry, and are generally grouped with the steppe (BSk) climates.

In the Eastern Hemisphere, this climate regime is found within interior Eurasia, east-central Asia, and parts of India. Within Europe, the Dfa climate type is present near the Black Sea in southern Ukraine, the Southern Federal District of Russia, southern Moldova, Serbia, parts of southern Romania, and Bulgaria,[13][14] but tends to be drier and can be even semi-arid in these places. In East Asia, this climate exhibits a monsoonal tendency with much higher precipitation in summer than in winter, and due the effects of the strong Siberian High much colder winter temperatures than similar latitudes around the world, however with lower snowfall, the exception being western Japan with its heavy snowfall. Tōhoku, between Tokyo and Hokkaidō and Western coast of Japan also has a climate with Köppen classification Dfa, but is wetter even than that part of North America with this climate type. A variant which has dry winters and hence relatively lower snowfall with monsoonal type summer rainfall is to be found in north-eastern China including coastal regions of the Yellow Sea and over much of the Korean Peninsula; it has the Köppen classification Dwa. Much of central Asia, northwestern China, and southern Mongolia have a thermal regime similar to that of the Dfa climate type, but these regions receive so little precipitation that they are more often classified as steppes (BSk) or deserts (BWk).

This climate zone does not exist at all in the southern hemisphere, where the only landmass that enters the upper-middle latitudes, South America, tapers too much to have any place that gets the combination of snowy winters and hot summers. Marine influences preclude Dfa, Dwa, and Dsa climates in the southern hemisphere.

Cool summer subtype

Regions with cool summer humid continental climates

| Moscow | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Areas featuring this subtype of the continental climate have an average temperature in the warmest month below 22 °C. Summer high temperatures in this zone typically average between 21–28 °C (70–82 °F) during the daytime and the average temperatures in the coldest month are generally far below the −3 °C (27 °F) (or 0 °C (32.0 °F)) isotherm. Frost-free periods typically last 3–5 months. Heat spells lasting over a week are rare. Winters are brisk and cold.[6]

The cool summer version of the humid continental climate covers a much larger area than the hot subtype. In North America, the climate zone covers from about 45°N to 50°N latitude mostly east of the 100th meridian. However, it can be found as far north as 54°N, and further west in the Canadian Prairie Provinces[citation needed] and below 40°N in the high Appalachians. In Europe this subtype reaches its most northerly latitude at nearly 61° N.[citation needed]

In the Western Hemisphere, high-altitude locations as South Lake Tahoe, California, and Aspen, Colorado, in the western United States exhibit local Dfb climates. The south-central and southwestern Prairie Provinces also fits the Dfb criteria from a thermal profile, but because of semi-arid precipitation portions of it are grouped into the BSk category. Much of New England falls into this subtype.[citation needed]

In Europe, it is found in Ukraine, Poland, Russia, Sweden, Finland,[14]Norway,[15]Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Romania and Hungary.[13] It has little warming or precipitation effects from the northern Atlantic.[14] The cool summer subtype is marked by mild summers, long cold winters and less precipitation than the hot summer subtype; however, short periods of extreme heat are not uncommon. Northern Japan has a similar climate.

In the Southern Hemisphere it exists in well-defined areas only in the Southern Alps of New Zealand,[citation needed] the Snowy Mountains of Australia, Kiandra, New South Wales, and as isolated microclimates of the southern Andes of Chile and Argentina.

Use in climate modeling

Since climate regimes tend to be dominated by vegetation of one region with relatively homogenous ecology, those that project climate change remap their results in the form of climate regimes as an alternative way to explain expected changes.[1]

See also

- Continental climate

References

^ ab Michal Belda; Eva Holtanová; Tomáš Halenka; Jaroslava Kalvová (2014-02-04). "Climate classification revisited: from Köppen to Trewartha" (PDF). Climate Research. 59: 1–14. Bibcode:2014ClRes..59....1B. doi:10.3354/cr01204..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Béla Berényi. Cultivated Plants, Primarily As Food Sources -- Vol II -- Fruit in Northern Latitudes (PDF). Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems. p. 1. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

^ "Halifax, Nova Scotia Temperature Averages". Weatherbase. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

^ "Milwaukee, Wisconsin Temperature Averages". Weatherbase. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

^ Antonio Ribeiro da Cunha; Edgar Ricardo Schöffel (November 2011). "20. The Evapotranspiration in Climate Classification". Measurements to Agricultural and Environmental Applications (PDF). InTech. pp. 392–396. ISBN 978-953-307-512-9. Retrieved 2015-02-22.

^ abcdef C. Donald Ahrens; Robert Henson (2015-01-01). Meteorology Today (11 ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 491–492. ISBN 1305480627. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

^ Steven Ackerman; John Knox (2006-03-08). Meteorology: Understanding the Atmosphere. Cengage Learning. p. 419. ISBN 1305147308. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

^ ab Andy D. Ward; Stanley W. Trimble (2003-12-18). Environmental Hydrology, Second Edition. CRC Press. pp. 31–34. ISBN 1566706165. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

^ Vijendra K. Boken; Arthur P. Cracknell; Ronald L. Heathcote (2005-03-24). Monitoring and Predicting Agricultural Drought : A Global Study: A Global Study. Oxford University Press. p. 349. ISBN 0198036787. Retrieved 2015-02-18.

^ Timothy Champion; Clive Gamble; Stephen Shennan; Alisdair Whittle (2009-08-15). "Prehistoric Europe". Left Coast Press. p. 14. ISBN 1598744631. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

^ National Climatic Data Center. "Illinois Normals" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

^ Gordon B. Bonan (2008-09-18). "6. Earth's Climate". Ecological Climatology: Concepts and Applications. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1107268869. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

^ ab Joseph Hobbs (2012-07-13). Fundamentals of World Regional Geography. Cengage Learning. p. 76. ISBN 1285402219. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

^ abc Michael Kramme (2012-01-03). Exploring Europe, Grades 5 - 8. Carson-Dellosa Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 1580376703. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

^ Peel, M. C. and Finlayson, B. L. and McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification". Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

(direkt: Final Revised Paper; PDF; 1,7 MB)