Anti-Serbian sentiment

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

General forms

|

Specific forms |

Social

|

Religious

|

Ethnic/National

|

Manifestations

|

Policies

|

Countermeasures

|

Related topics

|

Anti-Serbian sentiment or Anti-Serb sentiment (Serbian: антисрпска осећања / antisrpska osećanja) and also Anti-Serbism (антисрбизам / antisrbizam) or Anti-Serbdom (антисрпство / antisrpstvo) or Serbophobia (србофобија / srbofobija) is negative feeling in general towards Serbs as an ethnic group. Historically it has been a basis of persecution of ethnic Serbs.

A distinctive form of Anti-Serbism is Anti-Serbianism that can be defined as negative feeling in general towards Serbia as national state of Serbs, while another form is towards Republika Srpska, the Serb entity in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The best-known historic proponent of anti-Serb sentiment was the 19th- and 20th-century Croatian Party of Rights. The most extreme elements of this party became the Ustaše in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, a Croatian fascist organization that came to power during World War II and instituted racial laws that specifically targeted Serbs, Jews, Roma and dissidents. World War II persecution of Serbs included mass ethnic cleansing of Serbs and other minorities living in the Independent State of Croatia (1941-1945).

Contents

1 History

1.1 Before World War I

1.1.1 19th and early 20th century in Austro-Hungarian Croatia

1.1.2 Ottoman Macedonia

1.2 World War I

1.3 Interwar period

1.4 World War II

1.4.1 Independent State of Croatia and Ustashe

1.4.2 Albania

1.5 After World War II

1.6 Breakup of Yugoslavia

2 Contemporary and recent issues

2.1 Kosovo Albanians

2.2 Croatia

2.3 Montenegro

2.4 Hate speech and derogatory terms

2.4.1 Srbe na vrbe

3 Criticism and controversy

4 Alleged Serbophobes

5 Gallery

6 See also

7 References

8 Sources

9 Further reading

10 External links

History

Before World War I

19th and early 20th century in Austro-Hungarian Croatia

Ante Starčević

Anti-Serbian sentiment coalesced in 19th century Croatia when some of the Croatian intelligentsia planned the creation of a Croatian nation-state.[1]Croatia was at the time a part of the Kingdom of Hungary (Habsburg), an integral part of the Habsburg Monarchy, and Dalmatia and Istria separate Habsburg crown lands. Ante Starčević, the leader of the Party of Rights between 1851 and 1896, believed Croats should confront their neighbors, including Serbs.[2] He wrote, for example, that Serbs were an "unclean race" and with co-founder of his party, Eugen Kvaternik, denied the existence of Serbs or Slovenes in Croatia, seeing their political consciousness as a threat.[3][4] During the 1850s Starčević forged the term Slavoserb (Latin: sclavus, servus) to describe people supposedly ready to serve foreign rulers, initially used to refer to some Serbs and his Croat opponent and later applied to all Serbs by his followers.[5] The Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1878 probably contributed to the development of Starčević's anti-Serb sentiment: He believed that it increased chances for the creation of Greater Croatia.[6]David Bruce MacDonald, however, has explained Starčević's theories could only justify ethnocide but not genocide because Starčević intended to assimilate Serbs as "Orthodox Croats", and not to exterminate them.[7]

Starčević's ideas formed a basis for the destructive politics of his successor, Josip Frank, a Croatian Jewish lawyer and politician converted to Catholicism[8][9][10] who led numerous anti-Serbian incidents.[2] Josip Frank carried on Starčević's ideology, and defined Croat identity 'strictly in terms of Serbophobia'.[11] He opposed any cooperation between Croats and Serbs, and Djilas described him as "a leading anti-Serbian demagogue and the instigator of the persecution of Serbs in Croatia".[11] His followers, called Frankovci, would go on to become the most ardent Ustashe members.[11] Under Frank's leadership the Party of Rights became obsessively anti-Serb,[12][13] and such sentiments dominated Croatian political life in the 1880s.[14] British historian C. A. Macartney stated that because of the "gross intolerance" toward Serbs who lived in Slavonia, they had to seek protection from Count Károly Khuen-Héderváry, the Ban of Croatia-Slavonia, in 1883.[15] During his reign in 1883-1903, Hungary stimulated division and hatred between Serbs and Croats to further its Magyarization policy.[15] Carmichael writes that ethnic division between the Croats and the Serbs at the turn of the 20th century was stoked by a nationalist press and was "incubated entirely in the minds of extremists and fanatics, with little evidence that the areas in which Serbs and Croats had lived for many centuries in close proximity, such as Krajina, were more prone to ethnically inspired violence."[6] In 1902 major anti-Serb riots in Croatia were caused by an article written by Serbian nationalist writer Nikola Stojanović (1880–1964) titled Do istrage vaše ili naše (Till the destruction of you or us) which forecasted the result of an "inevitable" Serbian-Croatian conflict, that was reprinted in the Serb Independent Party's Srbobran magazine.[16]

Between the mid-19th and early 20th century there were two factions in the Catholic Church in Croatia: the progressive faction which preferred uniting Croatia with Serbia in a progressive Slavic country, and the conservative faction that opposed this.[17] The conservative faction became dominant by the end of the 19th century: The First Croatian Catholic Congress held in Zagreb in 1900 was unreservedly Serbophobic and anti-Orthodox.[17]

The term Serbophobe was used in literary and cultural circles before World War I. Croatian writers Antun Gustav Matoš and Miroslav Krleža casually described some political and cultural figures as "Serbophobes" (Krleža in the four-volume Talks with Miroslav Krleža, 1985, edited by Enes Čengić; they perceived an anti-Serbian animus in a person's behavior.[citation needed]

Ottoman Macedonia

The Society Against Serbs was a Bulgarian nationalist organization, established in 1897 in Thessaloniki, Ottoman Empire. The organization's activists were both "Centralists" and "Vrhovnists" of the Bulgarian revolutionary committees (the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization and the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee), and had by 1902 murdered at least 43 and wounded 52, owners of Serbian schools, teachers, Serbian Orthodox clergy, and other notable Serbs in the Ottoman Empire.[18] Bulgarians also used the term "Serbomans" for a people from notserbian origin, but with Serbian self-determination in Macedonia.

World War I

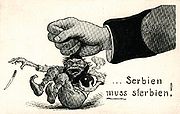

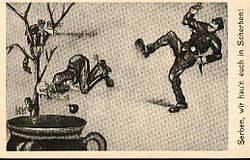

Austro-Hungarian propaganda postcard saying "Serbs, we'll smash you to pieces!"

After the Balkan Wars in 1912—1913, anti-Serb sentiment increased in the Austro-Hungarian administration of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[19]Oskar Potiorek, governor of Bosnia and Herzegovina, closed many Serb societies and significantly contributed to the anti-Serb mood before the outbreak of World War I.[19][20]

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg in 1914 led to the Anti-Serb pogrom in Sarajevo, where angry Croats and Muslims engaged in violence during the evening of 28 June and much of the day on 29 June. This led to a deep division along ethnic lines unprecedented in the city's history. Ivo Andrić refers to this event as the "Sarajevo frenzy of hate."[21] The crowds directed their anger principally at Serb shops, residences of prominent Serbs, the Serbian Orthodox Church, schools, banks, the Serb cultural society Prosvjeta, and the Srpska riječ newspaper offices. Two Serbs were killed that day.[22] That night there were anti-Serb riots in other parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire including Zagreb and Dubrovnik.[23][page needed][24] In the aftermath of the Sarajevo assassination anti-Serb sentiment ran high throughout the Habsburg Empire.[25] Austria-Hungary imprisoned and extradited around 5,500 prominent Serbs, sentenced 460 to death, and established the predominantly Muslim[26] special militia Schutzkorps which carried on the persecution of Serbs.[27]

The Sarajevo assassination became the casus belli for World War I.[28] Taking advantage of an international wave of revulsion against this act of "Serbian nationalist terrorism," Austria-Hungary gave Serbia an ultimatum which led to World War I. Although the Serbs of Austria-Hungary were loyal citizens whose majority participated in its forces during the war, anti-Serb sentiment systematically spread and members of the ethnic group were persecuted all over the country.[29] Austria-Hungary soon occupied the territory of the Kingdom of Serbia, including Kosovo, boosting already intense anti-Serbian sentiment among Albanians whose volunteer units were established to reduce the number of Serbs in Kosovo.[30] A cultural example is the jingle "Alle Serben müssen sterben" ("All Serbs Must Die"), which was popular in Vienna in 1914. (It was also known as "Serbien muß sterbien").[31]

Orders issued on 3 and 13 October 1914 banned the use of Serbian Cyrillic in the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, limiting it to use in religious instruction. A decree was passed on 3 January 1915, that banned Serbian Cyrillic completely from public use. An imperial order in 25 October 1915, banned the use of Serbian Cyrillic in the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina, except "within the scope of Serb Orthodox Church authorities".[32][33]

Interwar period

In the 1920s, Italian fascists accused Serbs of having "atavistic impulses" and they claimed that the Yugoslavs were conspiring together on behalf of "Grand Orient masonry and its funds". One anti-Semitic claim was that Serbs were part of a "social-democratic, masonic Jewish internationalist plot".[34]

The relations between Croats and Serbs were stressed at the very beginning of the Yugoslav state.[35] Opponents to the Yugoslav unification in the Croatian elite portrayed Serbs negatively, as hegemonists and exploiters, introducing Serbophobia into Croatian society.[35] It was reported that in Lika, there were serious tension between Croats and Serbs.[36] In post-war Osijek, the Šajkača hat was banned by the police but the Austro-Hungarian cap was freely worn, and in the school and judicial system the Orthodox Serbs were termed "Greek-Eastern".[37] There was voluntary segregation in Knin.[38]

A 1993 study made in the United States stated that Belgrade's centralist policies for the Kingdom of Yugoslavia led to increased anti-Serbian sentiment in Croatia.[39]

World War II

Ante Pavelić, leader of the viciously anti-Serbian Ustashe.

An entire Serb family lies slaughtered in their home following a raid by the Ustashe Militia, 1941.

Ustaše execute Serbs and Jews in Jasenovac as part of Serbian Genocide

Serbs including other Slavic people (mainly Poles and Russians) as well as non-Slavic (Jews and Roma) were not considered Aryans by Nazi Germany but as subhuman, inferior races (Untermenschen) and foreign races that could not be considered part of the Aryan master race.[40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54]

Anti-Serb sentiment increasingly infiltrated into German Nazi ideology after Adolf Hitler's appointment as chancellor in 1933. The roots can be found in his early life in Vienna,[55] and when he was informed about the Yugoslav coup d'état conducted by a group of pro-Western Serb officers in March 1941, he decided to punish all Serbs as the main enemies of his new Nazi order.[56] The ministry of Joseph Goebbels, with the support of the Bulgarian, Italian, and Hungarian press, was given the task of stimulating anti-Serb sentiment among Croats, Slovenians and Hungarians.[57] The propaganda of the Axis powers accused the group of persecution of minorities and the establishment of the concentration camps for ethnic Germans in order to justify an attack on Yugoslavia and Nazi Germany as a force which would save the Yugoslavian people from Serb nationalism.[57] The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was invaded again and occupied by Axis powers.

Ustaše soldiers sawing off the head of Branko Jungić, an ethnic Serb, near Bosanska Gradiška.

A knife nicknamed "Srbosjek" or "Serbcutter", strapped to the hand, which was used by the Ustaše Militia for the speedy killing of inmates in Jasenovac.

Independent State of Croatia and Ustashe

The Axis occupation of Serbia enabled the Ustashe, a Croatian fascist[58] and terrorist organization, to follow their extreme anti-Serbian ideology in the Independent State of Croatia.[59] Their anti-Serb sentiment was racist and genocidal.[60][61] The new Croatian government adopted racial laws, similar to those in Nazi Germany, aimed at Jews, Roma people and Serbs, who were all defined as "aliens outside the national community"[62] and persecuted throughout World War II throughout the Independent State of Croatia (NDH).[63] Between 100,000[64] and 700,000[65] Serbs were killed in Croatia by the Ustaše and their Axis allies. Overall, the number of Serbs killed in World War II in Yugoslavia was about 350,000, the majority massacred by various fascist forces.[64][66]

Some priests of the Croatian Catholic Church participated in these Ustaša massacres and the mass conversion of Serbs to Catholicism.[67] During the war, about 250,000 people of Orthodox faith that were living within the territory of the NDH were either forced or coerced into converting to Catholicism by the Ustaša authorities.[68] One of the reasons for the close cooperation of the part of Catholic clergy was their anti-Serb position.[69]

Albania

Xhafer Deva recruited Kosovo Albanians to join the Waffen-SS.[70] The 21st Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Skanderbeg (1st Albanian) was formed on 1 May 1944,[71] composed of ethnic Albanians, named after Albanian national hero Skanderbeg who fought the Ottomans in the 15th century.[72] The division had a strength of 6,500 men at the time of its creation[73] and was better known for murdering, raping, and looting in predominantly Serbian areas than for participating in combat operations on behalf of the German war effort.[74] With the Allied victory in the Balkans imminent, Deva and his men attempted to purchase weapons from withdrawing German soldiers in order to organize a "final solution" of the Slavic population of Kosovo. Nothing came of this as the powerful Yugoslav Partisans prevented any large-scale ethnic cleansing of Slavs from occurring.[75]

After World War II

Nearly four decades later, in the 1986 draft of the Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, concern was expressed that Serbophobia, together with other things, could provoke the restoration of Serbian nationalism with dangerous consequences.[76] The 1987 Yugoslav economic crisis, and different opinions within Serbia and other republics about what were the best ways to resolve it, exacerbated growing anti-Serbian sentiment among non-Serbs, but also enhanced Serbian support for Serbian nationalism.[77]

Breakup of Yugoslavia

@media all and (max-width:720px).mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinnerwidth:100%!important;max-width:none!important.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsinglefloat:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center

During the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s anti-Serb sentiment flooded Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo,[78] and because of its independence and historical association with Serbophobia, the Independent State of Croatia would sometimes serve as rallying symbol for people who intended to proclaim aversion toward Serbia.[79] It also worked vice versa. And while Serbian nationalism of the time is well-known, anti-Serb sentiment was present among all non-Serb nations of Yugoslavia during its breakup.[80]

In 1997 the FR Yugoslavia submitted claims to the International Court of Justice that Bosnia and Herzegovina was responsible for the acts of genocide committed against the Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which had been incited by anti-Serb sentiment and rhetoric communicated through all forms of the media. For example, The Novi Vox, a Muslim youth paper, published a poem titled "Patriotic Song" with the following verses: "Dear mother, I'm going to plant willows; We'll hang Serbs from them; Dear mother, I'm going to sharpen knives; We'll soon fill pits again."[81] The paper Zmaj od Bosne published an article with a sentence saying "Each Muslim must name a Serb and take oath to kill him."[81] The radio station Hajat broadcast "public calls for the execution of Serbs."[81]

Anti-Serbian sentiment remained largely present in the United Kingdom and other European states for many years after the Yugoslav wars ended.[82]

Outside the Balkans, Noam Chomsky observed that not just the government of Serbia, but also the people, were reviled and threatened. He described the jingoism as "a phenomenon I have not seen in my lifetime since the hysteria whipped up about 'the Japs' during World War II".[83]

At a 2012 book signing in Prague, Madeleine Albright, the United States Secretary of State during the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, received backlash from a pro-Serbian Czech organization whose protesters carried photos of Serbian victims of the Kosovo War. She was filmed responding to them with, "disgusting Serbs, get out!"[84]

Contemporary and recent issues

The 2016 UK "Leave Europe" campaign included explicitly anti-Serbian sentiment, based on the UK Defence Minister's negative remarks concerning Serbia.[85]

At a football game between Kosovo and Croatia played in Albania in October 2016, the fans together chanted murderous slogans against Serbs.[86] Both countries face FIFA hearings due to the incident.[87] Croat and Ukrainian sports fans have put up hate messages towards Serbs and Russians during a match of their national teams in the 2018 World Cup qualifier.[88]

Kosovo Albanians

Kosovo Albanian media depict Serbia and Serbs as threat to state frame and security, as disrupting institutional order, draining resources, being extremists, tied to criminal activities (in North Kosovo), and in retrospect as perpetrators of war crimes and violations of humans rights (reminding the public of Serbs as enemies). Serbs are blamed for inducing the Kosovo War, and since the war are negatively characterized as uncooperative, aggressive, extremist while the Serbian crimes in the war are termed "genocide".[89]

Croatia

Entrance to "Zagrebački zbor" in 1942, it served as a transit camp during the existence of Independent State of Croatia.

The Croatian usage of the Ustashe salute Za dom spremni, the equivalent of Nazi salute Sieg Heil, is not banned. It is frequently used by Croatian nationalists and sports fans.[90]

In 2013 it was reported that a group of right-wing extremists had taken over the Croatian Wikipedia, editing mostly articles related to the Ustashe, whitewashing their crimes, and articles targeting Serbs.[91][92]

In the same year there were protests in several Croatian cities against introducing Serbian language and Cyrillic script as official in Vukovar.[93] Later signs with Cyrillic on administrative buildings were destroyed by Croatian veterans. [94]

Serbian politicians have recently accused Croatian politicians of anti-Serbian sentiment.[95] The US State Department has warned about pro-Ustashe and anti-Serb sentiment in Croatia.[96] According to the Serbian National Council, hate speech, threats and violence against Serbs rose by 57% in 2016.[97] On 12 February 2018, when Serbian President Vučić was to meet with Croatian government representatives in Zagreb, hundreds of demonstrators chanted the salute Za dom spremni! at the city square.[98]

Montenegro

Serbs of Montenegro have supposedly been pressured to declare themselves Montenegrins, following the 2006 referendum.[99][better source needed] A number of Serbian writers have recently been removed from the school curriculum in Montenegro, which was described as creation of an "anti-Serb atmosphere" by a Serbian MP.[100]

Hate speech and derogatory terms

Among derogatory terms for Serbs are "Vlachs" (Власи / Vlasi)[101] and "Chetniks" (четници / četnici) used by Croats and Bosniaks;[102]Shkije by Albanians;[103][104] while Čefurji is used in Slovenia for immigrants from other former Yugoslav republics.[105]

Srbe na vrbe

Graffiti calling for murder of Serbs, in front of the Archbishopric bookshop in Split, Croatia.

The slogan Srbe na vrbe! (Србе на врбе), meaning "Hang Serbs from the willow trees!" (lit. "Serbs on willows!") originates from a poem by the Slovene politician Marko Natlačen published in 1914, at the beginning of the Austro-Hungarian war against Serbia.[106][107] It was popularized before World War II by Mile Budak,[108] the chief architect of Ustaše ideology against Serbs. During World War II there were mass hangings of Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia as part of the Ustaše persecution of the Serbs.

In present-day Croatia, Croatian neo-Nazis, extreme nationalists and people who oppose the return of Serb refugees often use the slogan. Graffiti with the phrase is common, and was noted in the press when it was found painted on a church in 2004,[109] 2006,[110] and on another church in 2008.[111] In 2010, a banner displaying the slogan appeared in the midst of tourist season at the entrance to Split, a major tourist hub in Croatia, during a Davis Cup tennis match between the two countries. It was removed by police within hours,[112] and the banner's creator was later apprehended and charged with a felony.[113][114] A Serbian Orthodox church in Geelong, Australia, was spray-painted with the slogan, along with other neo-Nazi symbols, in 2016.[115]

Criticism and controversy

The description of Serbophobia has been controversial, as some sources state it runs contrary to the facts.[116] Some controversy with the term purportedly corresponds to its interplay with perceived historical revisionism practiced by the government of Slobodan Milošević in the 1990s and its later apologists, and the contention that Serbian writers constructed the "myth of Serbophobia," as "an anti-Semitism for Serbs, making them victims throughout history."[117] According to MacDonald, in the 1980s Serbs increasingly began to compare themselves to Jews as fellow victims in world history, which involved tragedising historic events, from the 1389 Battle of Kosovo to the 1974 Yugoslav Constitution, as every aspect of history was seen as yet another example of persecution and victimisation of Serbs at the hands of external negative forces.[118] The association with Jewish suffering is probably linked to the Croatian death camp, Jasenovac where it is estimated that 500,000-700,000 Serbs were killed in extremely cruel circumstances, along with fellow inmates who were Jews and Roma. The disputed historical facts of the camp are the subject of allegations of "Holocaust Denial" by the Croatian authorities.[119]

Critics associate the use of the term Serbophobia with the politics of Serbian nationalist victimization of the late 1980s and 1990s as described, for example, by former director of the International Crisis Group in the Balkans, Christopher Bennett.[120] According to Bennett, the idea of historic Serb martyrdom grew out of the thinking and writing of Dobrica Ćosić who developed a complex and paradoxical theory of Serb national persecution, which evolved over two decades between the late 1960s and the late 1980s into the Greater Serbian programme.[120] Serbian nationalist politicians have made associations to Serbian "martyrdom" in history (from the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 to the genocide during World War II) to justify Serbian politics of the 1980s and 1990s; these associations were exemplified in Slobodan Milošević's Gazimestan speech at Kosovo Polje in 1989. The reaction to this speech as well as to the use of the associated term Serbophobia remains a matter of heated debate.[120]

In late 1988, months before the Revolutions of 1989, Milošević accused his critics like the Slovenian leader Milan Kučan of "spreading fear of Serbia" as a political tactic.[121] Political scientist David Bruce MacDonald stated that Serbophobia was often likened to anti-Semitism, and expressed itself as a re-analysis of history where every event that had a negative effect on the Serbs was likened to a tragedy, and used to justify territorial expansion into neighbouring regions.[122]

Alleged Serbophobes

- Ante Pavelić

Oskar Potiorek — Austro-Hungarian general

Madeleine Albright — American politician.[123][124]

Baron Wladimir Giesl von Gieslingen — Austro-Hungarian general and diplomat.[125]

Edith Durham — British traveller writer.[126]

August Meyszner — Nazi German official.[127]

Ante Starčević — Croatian politician.[128]

Juraj Krnjević — Croatian politician.[129]

Pavel Milyukov — Russian politician.[130]

Hans Uebersberger — German politician.[131]

Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf — Austrian officer.[132]

Harry Hodgkinson — British writer.[133]

Ivan Šušteršič — Slovene politician.[134]

Josip Frank — Croatian politician.[135]

Johann von Pallavicini — Austro-Hungarian diplomat.[136]

Vladko Maček — Croatian politician.[137]

Josip Stadler — Croatian Catholic archbishop.[138]

Ivan Šarić — Croatian Catholic archbishop.[139]

Siegfried Kasche — German ambassador to Croatia.[140]

Eftimie Murgu — Romanian politician.[141]

Petar Draganov — Russian philologist.[142]

Vasil Radoslavov — Bulgarian politician.[143]

Sulejman Ugljanin — Serbian politician, representative of the Bosniak minority[144]

Gallery

Serbien muss sterbien! ("Serbia must die!"), an Austrian caricature, after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in 1914, depicting Serbia as an ape-like terrorist.

Devastated and robbed shops owned by Serbs in Sarajevo during the Anti-Serb pogrom in Sarajevo.

Austro-Hungarian soldiers executing Serb civilians during World War I.

The remains of Serbs executed by Bulgarian soldiers in the Surdulica massacre during World War I. An estimated 2,000–3,000 Serbian men were killed in the town during the first months of the Bulgarian occupation of southern Serbia.[145]

Order for Serbs and Jews to move out of their home in Zagreb, in the Nazi puppet state during World War II. Also, warning of forcible expulsion for Serbs and Jews who fail to comply.

Ustaše saw off the head of a Serb, Branko Jungić, in Grabovac, near the town of Bosanska Gradiška.

Ruins of the Church of Holy Salvation, Prizren which was built circa 1330 and destroyed during the 2004 unrest in Kosovo.

14th-century icon from Our Lady of Ljeviš in Prizren, which was damaged in 2004 by rioters.

See also

- Persecution of Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia

- Anti-Serb riots in Sarajevo

- 1991 anti-Serb riot in Zadar

- Panda Bar incident

- Podujevo bus bombing

- Goraždevac murders

- Serbian Question

References

^ Kurt Jonassohn; Karin Solveig Björnson (January 1998). Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations: In Comparative Perspective. Transaction Publishers. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-4128-2445-3. Retrieved 30 August 2013.Anti-Serbian sentiment had already been expressed throughout the nineteenth century when Croatian intellectuals began to make plans for their own national state. They viewed the presence of more than one million Serbs in Krajina and Slavonia as intolerable.

.mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ ab Meier 2013, p. 120.

^ Carmichael 2012, p. 97.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0For Starčević... Serbs were 'unclean race' ... Along with ... Eugen Kvaternik he believed that 'there could be no Slovene or Serb people in Croatia because their existence could only be expressed in the right to a separate political territory.

^ John B. Allcock; Marko Milivojević; John Joseph Horton (1998). Conflict in the former Yugoslavia: an encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-87436-935-9. Retrieved 1 September 2013.Starcevic was extremely anti-Serb, seeing Serb political consciousness as a threat to Croats.

^ Tomasevich (2001), p. 3In polemics of the 1850's, Starčević also coined a misleading term - "Slavoserb", derived from the Latin word "sclavus" and "servus" to denote persons ready to serve foreign rulers against their own people.

^ ab Carmichael 2012, p. 97.

^ MacDonald 2002, p. 87.

^ Ognjen Kraus (1998, p. 174)

^ Gregory C. Ference (2000). "Frank, Josip". In Richard Frucht. Encyclopedia of Eastern Europe: From the Congress of Vienna to the Fall of Communism. New York & London: Garland Publishing. pp. 276–277.

^ (in Croatian) "Eugen Dido Kvaternik, Sjećanja i zapažanja 1925-1945, Prilozi za hrvatsku povijest.", Dr. Jere Jareb, Starčević, Zagreb, 1995.,

ISBN 953-96369-0-6, str. 267.: Josip Frank pokršten je, kad je imao 18 godina.

^ abc Trbovich 2008, p. 136.

^ Robert A. Kann (1980). A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526-1918. University of California Press. p. 447. ISBN 978-0-520-04206-3. Retrieved 30 August 2013.... in the case of Frank's followers... strongly anti-Serb

^ Stephen Richards Graubard (1999). A New Europe for the Old?. Transaction Publishers. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4128-1617-5. Retrieved 30 August 2013.Under Josip Frank, who carried the rightists into a new era, the party became obsessively anti- Serbian.

^ Jelavich & Jelavich 1986, p. 254.

^ ab MacDonald 2002, p. 88.

^ Bilandžić, Dušan (1999). Hrvatska moderna povijest. Golden marketing. p. 31. ISBN 953-6168-50-2.

^ ab Ramet 1998, p. 155Thus, from the mid-nineteenth century until the 1920s, the church in Croatia was riven into two factions: the progressives, who favored the incorporation of Croatia into a liberal Slavic state ... and the conservatives,... who were loath to bind Catholic Croatia to Orthodox Serbia. ... By 1900 the exclusivist orientation seems to have gained the upper hand in Catholic circles and the First Croatian Catholic Congress, held in Zagreb that year, was implicitly anti-Orthodox and anti-Serb.

^

Hadži Vasiljević, Jovan (1928). Četnička akcija u Staroj Srbiji i Maćedoniji. p. 14.

^ ab Richard C. Frucht (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 644. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6.The Balkan Wars left Serbia as the region's strongest power. Serbia's relationship with Austria-Hungary remained antagonistic, and the Habsburg administration in Bosnia-Hercegovina became anti-Serb...the governor of Bosnia declared state of emergency, dissolved the parliament,... and closed down many Serb associations...

^ Mitja Velikonja (5 February 2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Texas A&M University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3.The anti-Serb policy and mood that emerged in the months leading up to the First World War were the result of the machinations of Gen. Oskar von Potiorek (1853-1933), Bosnia-Herzegovina's heavy-handed military governor.

^ Daniela Gioseffi (1993). On Prejudice: A Global Perspective. Anchor Books. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-385-46938-8....Andric describes the "Sarajevo frenzy of hate" that erupted among Muslims, Roman Catholics, and Orthodox believers following the assassination on June 28, 1914, of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo...

^ Robert J. Donia (29 June 1914). Sarajevo: a biography. p. 123.

^ Joseph Ward Swain (1933). Beginning the twentieth century: a history of the generation that made the war. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

^ John Richard Schindler (1995). A hopeless struggle: the Austro-Hungarian army and total war, 1914-1918. McMaster University. p. 50....anti-Serbian demonstrations in Sarajevo, Zagreb and Ragusa.

^ Christopher Bennett (January 1995). Yugoslavia's Bloody Collapse: Causes, Course and Consequences. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-1-85065-232-8.

^ Tomasevich 2001, p. 485.

^ Herbert Kröll (2008). Austrian-Greek encounters over the centuries: history, diplomacy, politics, arts, economics. Studienverlag. p. 55. ISBN 978-3-7065-4526-6....arrested and interned some 5.500 prominent Serbs and sentenced to death some 460 persons, a new Schutzkorps, an auxiliary militia, widened the anti-Serb repression.

^ Klajn 2007, p. 16.

^ Pavlowitch 2002, p. 94.

^ Banac 1988, p. 297.

^

Gustav Regler; Gerhard Schmidt-Henkel; Ralph Schock; Günter Scholdt (2007). Werke. Stroemfeld/Roter Stern. p. 46. ISBN 978-3-87877-442-6. Retrieved 31 August 2013.Mit Kreide war an die Waggons geschrieben: »Jeder Schuß ein Russ', jeder Stoß ein Franzos', jeder Tritt ein Brit', alle Serben müssen sterben.« Die Soldaten lachten, als ich die Inschrift laut las. Es war eine Aufforderung, mitzulachen.

^

Andrej Mitrović, Serbia's great war, 1914-1918 p.78-79. Purdue University Press, 2007.

ISBN 1-55753-477-2,

ISBN 978-1-55753-477-4

^

Ana S. Trbovich (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Oxford University Press. p. 102.

^ Burgwyn, H. James. Italian foreign policy in the interwar period, 1918-1940. p. 43. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1997.

^ ab Božić 2010, p. 185.

^ Božić 2010, p. 187.

^ Božić 2010, p. 188.

^ Božić 2010, pp. 203–204.

^ United States. Congress. Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (1993). Human rights and democratization in Croatia. The Commission. p. 3. Retrieved 31 August 2013.Increasing centralization by Belgrade, however, encouraged anti-Serbian sentiment in Croatia,

^ Historical Dictionary of the Holocaust - Page 175 Jack R. Fischel - 2010 The policy of Lebensraum was also the product of Nazi racial ideology, which held that the Slavic peoples of the east were inferior to the Aryan race.

^ Hitler's Home Front: Wurttemberg Under the Nazis, Jill Stephenson p. 135, Other non-'Aryans' included Slavs, Blacks and Roma .

^ Race Relations Within Western Expansion - Page 98 Alan J. Levine - 1996 Preposterously, Central European Aryan theorists, and later the Nazis, would insist that the Slavic-speaking peoples were not really Aryans

^ The Politics of Fertility in Twentieth-Century Berlin - Page 118 Annette F. Timm - 2010 The Nazis' singleminded desire to "purify" the German race through the elimination of non-Aryans (particularly Jews, Gypsies, and Slavs)

^ Curta 2001, p. 9, 26–30.

^ Jerry Bergman, "Eugenics and the Development of Nazi Race Policy", Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith PSCF 44 (June 1992):109–124

^ Götz Aly, Peter Chroust, Christian Pross, Cleansing the Fatherland: Nazi Medicine and Racial Hygiene, The Johns Hopkins University Press, (August 1, 1994)

ISBN 0-8018-4824-5

^ The Holocaust and History The Known, the Unknown, the Disputed, and the Reexamined Edited by Michael Berenbaum and Abraham J. Peck, Indiana University Press page 59 "Pseudoracial policy of Third Reich(...)Gypsies, Slavs, blacks, Mischlinge, and Jews are not Aryans."

^ Honorary Aryans: National-Racial Identity and Protected Jews in the Independent State of Croatia Nevenko Bartulin

Palgrave Macmilla, Nevenko Bartulin - 2013 page 7- "According to Jareb, the National Socialists regarded the Slavs as 'racially less valuable' non-Aryans"

^ Nazi Germany,Richard Tames - 1985 -"Hitler's vision of a Europe dominated by a Nazi "Herrenvolk" in which Slavs and other "non-aryans" page 65

^ Modern Genocide: The Definitive Resource and Document Collection Paul R. Bartrop, Steven Leonard Jacobs page 1160, "This strict dualism between the "racially pure" Aryans and all others—especially Jews and Slavs—led in Nazism to the radical outlawing of all "non-Aryans" and to their enslavement and attempted annihilation"

^ World Fascism: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1 Cyprian Blamires page 63 "the "racially pure" Aryans and all others—especially Jews and Slavs— led in Nazism to the radical outlawing of all "non-Aryans" and to their enslavement and attempted annihilation

^ The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery, Volume 1; Volume 7 By Junius P. Rodriguez page 464

^ Emil L. Fackenheim: A Jewish Philosopher's Response to the Holocaust

David Patterson, page 23

^ Historical Dictionary of the Holocaust

Jack R. Fischel - 2010 Lebensraum was also the product of Nazi racial ideology, which held that the Slavic peoples of the east were inferior to the Aryan race[page needed]

^

Stephen E. Hanson; Willfried Spohn (1 January 1995). Can Europe Work?: Germany and the Reconstruction of Postcommunist Societies. University of Washington Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-295-80188-9. Retrieved 30 August 2013.German anti-Serbian sentiment increased after Hitler's ascent to power in 1933. His Serbophobia, rooted in the years of his youth spent in Vienna, was virulent. As a result, Nazi ideology became permeated with anti-Serbian sentiment.

^ Pavlowitch 2008, p. 16.

^ ab Klajn 2007, p. 17.

^ "Ustasa (Croatian political movement) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

^

Tomasevich (2001), p. 391...Serbia proper was under strict German occupation, allowed Ustashas to pursue their radical anti-Serbian policy

^ Aleksa Djilas (1991). The Contested Country: Yugoslav Unity and Communist Revolution, 1919-1953. Harvard University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-674-16698-1. Retrieved 31 August 2013.It was racist and genocidal hatred of people who merely had different national consciousness

^ Rory Yeomans; Anton Weiss-Wendt (1 July 2013). Racial Science in Hitler's New Europe, 1938-1945. U of Nebraska Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-8032-4605-8. Retrieved 31 August 2013.The Ustasha regime ... inaugurated the most brutal campaign of mass murder against civilian population that Southern Europe has ever witnessed... The campaign of mass murder and deportation against the Serb population was initially justified on racial scientific principles. ...

^ Frederick C. DeCoste; Bernard Schwartz (2000). The Holocaust's Ghost: Writings on Art, Politics, Law and Education ; [includes Papers from the Conference, Held at the University of Alberta, Oct. 1997]. University of Alberta. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-88864-337-7. Retrieved 2 September 2013.The new Croatian government quickly adopted Nazi-type racial laws and genocidal tactics to deal with Roma, Serbs and Jews, whom these laws termed "aliens outside the national community".

^ "Resistance to the Persecution of Ethnic Minorities in Croatia and Bosnia During World War II (9780773447455): Lisa M. Adeli: Books". Retrieved 16 January 2012.

^ ab McAdams, C. Michael (16 August 1992). "Croatia: Myth and Reality" (PDF). Retrieved 16 May 2015.

^ Žerjavić, Vladimir (1993). Yugoslavia – Manipulations with the number of Second World War victims. Croatian Information Centre. ISBN 0-919817-32-7.

^ "The Serbs and Croats: So Much in Common, Including Hate, May 16, 1991". The New York Times. 16 May 1991. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

^ Ramet 2006, p. 124.

^ Tomasevich (2001), p. 542

^ Tomasevich (2001), p. 391Close collaboration between Ustaša and part of catholic clergy followed... above all anti-Serbian...

^ Fischer 1999, p. 215.

^ Nafziger 1992, p. 21.

^ Judah 2002, p. 28.

^ Cohen 1996, p. 100.

^ Mojzes 2011, pp. 94–95.

^ Yeomans 2006, p. 31.

^ "SANU". Web.archive.org. 16 June 2008. Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 20 June 2012.The present depressing condition of the Serbian nation, with chauvinism and Serbophobia being ever more violently expressed in certain circles, favor of a revival of Serbian nationalism, an increasingly drastic expression of Serbian national sensitivity, and reactions that can be volatile and even dangerous.

^ Robert Bideleux; Professor Richard Taylor (15 April 2013). European Integration and Disintegration: East and West. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-134-77522-4. Retrieved 31 August 2013.By 1987 accelerating inflation and rapid depreciation of the dinar were strengthening Slovene and Croatian demands for sweping economic liberalization, but these were blocked by Serbia. This exacerbated the growing anti-Serbian sentiments among non-Serbs, but also enhanced Serbian support for Milošević's nationalism and his manipulation of the Kosovo issue, culminating in the abolition of the autonomy of that region.

^ Ramet 2006, p. 39.

^ Ramet 2007, p. 3Because of its independence from Belgrade (though not from Berlin) and because of its association with anti-Serb and anti-Allied politics, the NDH would later serve as rallying symbol for those who wanting to declare their antipathy toward Serbia (during the War of Yugoslav secession)...

^ Ramet 2006, p. 240Nationalist and Liberal Echoes in Other Republics Every republic and autonomous province was struck by nationalist outbursts in these years, and among all the non-Serbian nationalities, there were strong anti- Serbian feelings.

^ abc International Court of Justice 17 December 1997 Case Concerning Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishmnent of the Crime of Genocide. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

^ Clark, Neil (2008-01-14). "It's time to end Serb-bashing". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

^ Gallagher, Tom (5 August 2000). "The Lessons From Kosovo". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

^ "There's a 'Special Place in Hell' for Madeleine Albright. Here's Why". U.S. Uncut. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

^ "Brexit ..." inSerbia. June 2016.

^ "Kosovo-Croatia Match Marred by Anti-Serbian Chants". Balkan Insight.

^ "Kosovo & Croatia face Fifa hearings over anti-Serbian chanting". BBC.

^ "Croat and Ukrainian fans' hate message to Serbs and Russians". B92.

^ Zdravković-Zonta Helena (2011). "Serbs as threat the extreme negative portrayal of the Serb "minority" in Albanian-language newspapers in Kosovo". Balcanica (42): 165–215. doi:10.2298/BALC1142165Z.

^ Kristović, Ivica (22 November 2013). "Pozdrav 'Za dom spremni' ekvivalent je nacističkom 'Sieg Heil!'". Večernji list. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

^ "Hr.wikipedija pod povećalom zbog falsificiranja hrvatske povijesti" [Croatian Wikipedia under a scrutiny for fabricating Croatian history!] (in Croatian). Novi list. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

^ Sampson, Tim (1 October 2013). "How pro-fascist ideologues are rewriting Croatia's history". The Daily Dot. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

^ https://www.reuters.com/article/us-croatia-protest-idUSBRE91109C20130202

^ http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/vukovar-bilingualism-introduce-faces-violent-resistance

^ "Dacic: "The EU offered no real answer to the anti-Serbian policy in the region"". MFA.

^ "Slap for Croats: New report of Americans is warning on praising of Ustasha and Anti-Serb Feelings in Croatia". Telegraf.

^ "Intolerance Towards Serbs 'Escalates in Croatia': Report". Balkan Insight.

^ "Prve Haos U Zagrebu Ustaše skandiraju: "Za dom spremni"". Alo!.

^ Milacic, Slavisha Batko (2018-11-09). "Serbian question in Montenegro". Modern Diplomacy. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

^ Srpska, RTRS, Radio Televizija Republike Srpske, Radio Television of Republic of. "CG: U školskoj lektiri nema mjesta za srpske pisce". REGION - RTRS. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

^ Banac 1988, p. 257.

^ Pål Kolstø (2009). Media Discourse and the Yugoslav Conflicts: Representations of Self and Other. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-4094-9164-4. Retrieved 2 September 2013.The hostile 'them' were labelled either as the abstract but omnipresent 'aggressor' or as the stereotypical 'Chetniks' and 'Serbo-communists'. Other derogatory references in Večernji list,...

^ "Civil Rights Defense Minority Communities, March 2006" (PDF). 28 September 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

^ NIN. nedeljne informativne novine. Politika. 2005. p. 6.Албанци Србе зову Шкије, и то им је сасвим у реду, иако је то исто увредљиво као српски погрдни назив за Албанце

^ "Slovar novejšega besedja slovenskega jezika @ Portal Inštituta za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša ZRC SAZU".

^

Dr. Božo Repe (2005). "Slovene History – 20th century, selected articles" (PDF). Department of History of the University of Ljubljana. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

^

Petition of 120 Croatian intellectuals. "O Mili Budaku, opet: Deset činjenica i deset pitanja – s jednim apelom u zaključku" (in Croatian). Index.hr. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

^

Vinko Nikolić (1990). Mile Budak, pjesnik i mučenik Hrvatske: spomen-zbornik o stotoj godišnjici rođenja 1899-1989. Hrvatska revija. p. 55. ISBN 978-84-599-4619-3. Retrieved 30 August 2013....gdje je Budak, izgleda po prvi puta, upotrijebio krilaticu «Srbe na vrbe»

^

"Ominous Ustashe graffiti on churchyard wall of Church of the Dormition of the Most Holy Mother of God in Imotski". Information Service of the Serbian Orthodox Church. 28 April 2004. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

[permanent dead link][clarification needed]

^

"World Report 2006 – Croatia". Human Rights Watch. January 2006.

^

"Uvredljivi grafiti na Pravoslavnoj crkvi u Splitu (Offensive graffiti on the Serbian Orthodox church in Split)" (in Croatian). Nova TV/Dnevnik.hr. 18 January 2008. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

^

"Na ulazu u Split osvanuo sramotni transparent (Shameful banner appears at the entrance to Split)". Jutarnji list (in Croatian). 9 July 2010. Archived from the original on 11 July 2010. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

^

"Otkriven idejni začetnik izrade rasističkog transparenta – Antonio V. (23) osmislio transparent "Srbe na vrbe"". Večernji list (in Croatian). 23 July 2010. Archived from the original on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

^

Croatian Parliament (21 October 1997). "Kazneni zakon" (in Croatian). Narodne novine NN 110-1997. Retrieved 6 August 2010.Rasna i druga diskriminacija – Članak 174.

^ "Geelong church community horrified by anti-Serbian graffiti". SBS.

^

MacDonald (2002), pp. 82-88

^

MacDonald (2002), p. 83

^ MacDonald (2002), p. 7.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 June 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2016.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ abc

Comment: Serbia's War With History by C. Bennett, Institute for War & Peace Reporting, 19 April 1999

^ Communism O Nationalism!, Time Magazine, 24 October 1988

^ MacDonald, D. B. (2003), pp. 82-88

^ Brendan O'Shea (2012). Perception and Reality in the Modern Yugoslav Conflict: Myth, Falsehood and Deceit 1991-1995. Routledge. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-0-415-65024-3.

^ Marsden 2000.

^ William Henry Cooke; Edith Pierpont Stickney (1931). Readings in European International Relations Since 1879. Harper & Bros. p. 329.

^ The Nation and Athenæum. 38. Nation Publishing Company Limited. 1925. p. 491.

^ Tomasevich 2001, p. 78.

^ Current History and Forum ... 29. C-H Publishing Corporation. 1928. p. 88.

^ Aleksa Djilas (1991). The Contested Country: Yugoslav Unity and Communist Revolution, 1919-1953. Harvard University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-674-16698-1. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

^ Vladimir Nabokov (1970). The Provisional Government. J. Wiley. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-470-62805-8.

^ Ritchie Robertson; Edward Timms (1994). The Habsburg legacy: national identity in historical perspective. Edinburgh University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-7486-0487-6.

^ Franklin Pierce Olson (1952). The Foreign Policy of Montenegro, 1908-1912. Department of History, Stanford University. p. 28.

^ James Pettifer (2008). "Obituary: Harry Hodgkinson". London, United Kingdom: The Independent. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

^ John Paul Newman (25 June 2015). Yugoslavia in the Shadow of War: Veterans and the Limits of State Building, 1903–1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-107-07076-9.

^ Alexander Watson (7 August 2014). Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary at War, 1914-1918. Penguin Books Limited. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-14-192419-9.

^ T. Jonescu. Some personal impressions. Рипол Классик. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-176-40121-1.

^ Milan Stojadinović (1979). La Yougoslavie entre les deux guerres: ni le pacte, ni la guerre. Nouvelles Editions Latines. p. 303. ISBN 978-2-7233-0071-1.

^ L'Eglise catholique en Autriche. Publication Univ Rouen Havre. 1 December 2005. p. 72. ISBN 978-2-87775-396-8.

^ Orthoodox East. p. 174.

^ Lazo M. Kostić (1981). The Holocaust in the "Independent State of Croatia": An Account Based on German, Italian and Other Sources. Liberty. p. 137.

^ Revue de Transylvanie. 3–4. 1936. p. 458.

^ Hugo Marcuse (1908). Serbien und die Revolutionsbewegung in Makedonien: ein Beitrag zur makedonischen Frage. W. Kraus. p. 162.

^ Les Bulgares peints par eux-mm̂es: documents et commentaires. Payot. 1917. p. 219.

^ "Bosniak politician promises defeat of 'fascist state - Serbia'". balkaneu.com. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

^ Mitrović 2007, p. 223.

Sources

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

- Books

Banac, Ivo (1988). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9493-2.

Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme.

Carmichael, Cathie (2012). Ethnic Cleansing in the Balkans: Nationalism and the Destruction of Tradition. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-47953-5. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Ekmečić, Milorad (2000). Srbofobija i antisemitizam. Beli anđeo.

Klajn, Lajčo (2007). The Past in Present Times: The Yugoslav Saga. University Press of America. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-0-7618-3647-6.

Korb, Alexander (2010). "A Multipronged Attack: Ustaša Persecution of Serbs, Jews, and Roma in Wartime Croatia". Eradicating Differences: The Treatment of Minorities in Nazi-Dominated Europe. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 145–163.

Jelavich, Charles; Jelavich, Barbara (1986). The Establishment of the Balkan National States, 1804-1920. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-96413-3.

Jovanović, Batrić (1989). Peta kolona antisrpske koalicije : odgovori autorima Etnogenezofobije i drugih pamfleta.

MacDonald, David Bruce (2002). Balkan Holocausts?: Serbian and Croatian Victim Centred Propaganda and the War in Yugoslavia. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-6466-X.

McCormick, Rob (2008). "The United States' Response to Genocide in the Independent State of Croatia, 1941–1945". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 3 (1): 75–98.

Meier, Viktor (2013). Yugoslavia: A History of Its Demise. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-66511-2. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

Mitrović, Andrej (2007). Serbia's Great War, 1914-1918. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-476-7.

Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2002). Serbia: The History behind the Name. London: Hurst & Company.

Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2008). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-70050-4.

Ramet, Sabrina P. (1998). Nihil Obstat: Religion, Politics, and Social Change in East-Central Europe and Russia. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2070-8.

Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918-2005. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

Ramet, Sabrina P. (2007). The Independent State of Croatia 1941-45. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-44055-4.

Štrbac, Savo (2015). Gone with the Storm: A Chronicle of Ethnic Cleansing of Serbs from Croatia. Knin-Banja Luka-Beograd: Grafid, DIC Veritas.

Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941-1945: Occupation and Collaboration. 2. San Francisco: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3615-4.

Trbovich, Ana S. (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533343-5.

Wingfield, Nancy M., ed. (2003). Creating the Other: Ethnic Conflict & Nationalism in Habsburg Central Europe. Berghahn Books.

- Journals

Božić, Sofija (2010). "Serbs in Croatia (1918-1929): Between the myth of "Greater-Serbian Hegemony" and social reality". Balcanica. 41: 185–208.

- News articles

Marsden, Chris (16 March 2000). "British documentary substantiates US-KLA collusion in provoking war with Serbia". WSWS.

Further reading

Антисрпство у уџбеницима историје у Црној Гори. Српско народно вијеће. 2007. ISBN 978-9940-9009-1-5.

(in Serbian)

Mitrović, Jeremija D. (2005). Srbofobija i njeni izvori. Službeni glasnik.

Ћосић, Добрица (2004). Српско питање. Филип Вишњић.

(in Serbian)

Popović, Vasilj (1940). Европа и српско питање у периоду ослобођења (1804-1918). Geca Kon.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anti-Serb sentiment. |

Ovey, Michael. "Victim Chic? The Rhetoric of victimhood". Cambridge Papers.

Globalizing the Holocaust: A Jewish "useable past" in Serbian nationalism, by David McDonald, University of Otago, New Zealand

Neue Serbophilie und alte Serbophobie, "New Serbophilia and Old Serbophobia", a 2000 Junge Welt article by Werner Pirker (in German)

Marc Fumaroli at the Wayback Machine (archive index), a 1999 article by Catherine Argand from Lire, a French literary magazine (in French)

Europa e nuovi nazionalismi, a 2001 article by Luca Rastello (in Italian)

Бомбы или гражданская война at the Wayback Machine (archive index), a 2000 Sevodnya article by Alexei Makarkin (in Russian)

Ku është antimillosheviqi?, a 2000 AIM article by Igor Mekina (in Albanian)