Eisteddfod

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Wales |

|---|

|

History |

People |

Languages

|

Traditions

|

Mythology and folklore

|

Cuisine

|

Festivals

|

Religion |

Art |

Literature

|

Music and performing arts

|

Media

|

Sport

|

Monuments

|

Symbols

|

|

In Welsh culture, an eisteddfod (Welsh: [ə(i)ˈstɛðvɔd] ('ay-steth-vod'), plural eisteddfodau Welsh: [ə(i)stɛðˈvɔda(ɨ)]) is a Welsh festival of literature, music and performance. The tradition of such a meeting of Welsh artists dates back to at least the 12th century, when a festival of poetry and music was held by Rhys ap Gruffydd of Deheubarth at his court in Cardigan in 1176, but the decline of the bardic tradition made it fall into abeyance. The current format owes much to an 18th-century revival arising out of a number of informal eisteddfodau. The closest English equivalent to eisteddfod is "session"; the word is formed from two Welsh morphemes: eistedd, meaning "sit", and bod, meaning "be".[1] In some countries, the term eisteddfod is used for certain types of performing arts competitions that have nothing to do with Welsh culture.[citation needed]

Pronunciation of 'Eisteddfod'

Contents

1 History

2 Eisteddfod revival

3 List of Welsh eisteddfodau

3.1 National Eisteddfod

3.2 Urdd National Eisteddfod

3.3 The International Eisteddfod

3.4 Other eisteddfodau in Wales

4 Other Celtic eisteddfod-like events

5 Eisteddfod outside Wales

5.1 United Kingdom

5.2 Argentina

5.3 Australia

5.4 South Africa

5.5 United States

6 See also

7 References

8 External links

History

The date of the first eisteddfod is a matter of much debate among scholars[who?], but boards for the judging of poetry existed in Wales from at least the early 12th century[citation needed]. These judging boards had probably derived from ancient Celtic bardic traditions. The first recorded eisteddfod was held under the auspices of The Lord Rhys at Cardigan Castle in 1176. There he held a gathering to which were invited poets and musicians from all parts of Wales. A chair at the Lord's table was awarded to the best poet and musician, a tradition that prevails in the modern day National Eisteddfod. The earliest large-scale eisteddfod that is historically known is the Carmarthen Eisteddfod in 1451 under Thomas ap Gruffydd of Llandeilo (his illegitimate son was the soldier Rhys ap Thomas).[citation needed]

The next recorded large-scale eisteddfod was held in Caerwys in 1568. The prizes awarded were a miniature silver chair to the successful poet, a little silver crwth to the winning fiddler, a silver tongue to the best singer, and a tiny silver harp to the best harpist. Originally, the contests were limited to professional Welsh bards who were paid by the nobility. In the 16th century, Elizabeth I of England commanded that the bards be examined and licensed to ensure performance standards. But interest in the Welsh arts declined during the 17th and 18th centuries, leading to the standard of the main eisteddfod deteriorating. Gatherings also became more informal; poets would often meet in taverns and open spaces and have "assemblies of rhymers". These meetings kept traditions alive; the winners even still received a chair.[citation needed]

A chair was a prized award because of its perceived social status. Throughout the medieval period, high-backed chairs with arm rests were reserved for royalty and high-status leaders in military, religious and civic affairs. As most ordinary people sat on stools until the 1700s, an armchair conveyed status to a winning bard.

In 1789, Thomas Jones organised an eisteddfod in Corwen, where for the first time the public were admitted. The success of this event led to a revival of interest in Welsh literature and music[according to whom?]. The earliest known surviving Bardic chair made specifically for an Eisteddfod was built in Carmarthen in 1819.[citation needed]

Eisteddfod revival

Iolo Morganwg (bardic name of Edward Williams) founded "Gorsedd Beirdd Ynys Prydain" (Gorsedd of the Bards of the Isle of Britain) in 1792 to restore and replace the ancient eisteddfod. The first eisteddfod of the revival was held on Primrose Hill, London.[citation needed]

The Gentleman's Magazine of October 1792 reported on the revival of the eisteddfod tradition.[citation needed]

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

This being the day on which the autumnal equinox occurred, some Welsh bards resident in London assembled in congress on Primrose Hill, according to ancient usage. Present at the meeting was Edward Jones who had published his "The Musical and Poetical Reelicks of the Welsh Bards" in 1784 in a belated effort to try to preserve the native Welsh traditions being so ruthlessly stamped out by the new breed of Methodists.

The Blue Books' notorious attack on the character of the Welsh as a nation in 1846 led to public anger and the belief that it was important for the Welsh to create a new national image. By the 1850s people[who?] began to talk of a national eisteddfod to showcase Wales's culture. In 1858 John Williams ab Ithel held a "National" Eisteddfod complete with Gorsedd in Llangollen. "The great Llangollen Eisteddfod of 1858" was a significant event. Thomas Stephens won a prize with an essay demolishing the claim of John Williams (the event's organiser) that Madoc discovered America. As Williams had expected Stephens's essay to reinforce the myth, he was not willing to award the prize to Stephens and, it is recorded, "matters became turbulent". This eisteddfod also saw the first public appearance of John Ceiriog Hughes who won a prize for a love poem, Myfanwy Fychan of Dinas Brân, which became an instant hit. There is speculation[according to whom?] that this was a result of its depiction of a "deserving, beautiful, moral, well-mannered Welshwoman", in stark contrast to The Blue Books' depiction of Welsh women as having questionable morals.

The National Eisteddfod Council was created after Llangollen, and the Gorsedd subsequently merged with it. The Gorsedd holds the right of proclamation and of governance while the Council organises the event. The first true National Eisteddfod organised by the Council was held in Denbigh in 1860 on a pattern that continues to the present day.

List of Welsh eisteddfodau

National Eisteddfod

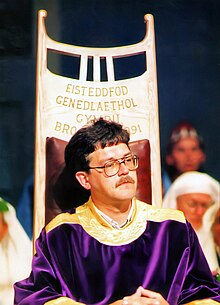

Prifardd Robin Owain in the bardic chair, 1991

The National Eisteddfod of Wales, Mold 2007

One of the most important eisteddfods is the National Eisteddfod of Wales, the largest festival of competitive music and poetry in Europe. Its eight days of competitions and performances, entirely in the Welsh language, are staged annually in the first week of August, usually alternating between north and south Wales.[2] Competitors typically number 6,000 or more, and overall attendances generally exceed 150,000 visitors.[3]

Urdd National Eisteddfod

Another important eisteddfod in the calendar is 'Eisteddfod Yr Urdd', or the Youth Eisteddfod. Organised by Urdd Gobaith Cymru, it involves Welsh children from nursery age to 25 in a week of competition in singing, recitation, dancing, acting and musicianship during the summer half-term school holiday. The event is claimed to be Europe's premier youth arts festival.[4] Regional heats are held in advance and, as with the National Eisteddfod, the Urdd Eisteddfod is held in a different location each year. With the establishment of the Urdd headquarters in the Wales Millennium Centre, the eisteddfod will return to Cardiff every four years.

The International Eisteddfod

The International Eisteddfod is held annually in Llangollen, Denbighshire each year in July. Choirs, singing groups, folk dancers and other groups attend from all over the world, sharing their national folk traditions in one of the world's great festivals of the arts. It was set up in 1947 and begins with a message of peace. In 2004, it was (unsuccessfully) nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by Terry Waite, who has been actively involved with the eisteddfod.

Other eisteddfodau in Wales

Smaller-scale local eisteddfodau are held throughout Wales. One of the best known is the Maes Garmon Eisteddfod, Mold (Welsh: Eisteddfod Ysgol Maes Garmon, Wyddgrug). Schools hold eisteddfodau as competitions within the school: a popular date for this is Saint David's Day.

Other Celtic eisteddfod-like events

There are some Celtic language specific cultural festivals similar to eisteddfodau. In Cornwall, an analogous event is known as "Esethvos Kernow" (Cornish for "Eisteddfod of Cornwall") and is connected with Gorseth Kernow. The Scottish Gaelic Mod and the Breton Kan ar Bobl also have similarities to an eisteddfod.

The eisteddfod idea has been taken up by non-Welsh speakers in the Channel Islands, particularly for the preservation of the local dialects Jèrriais and Guernésiais, and is called such. See Jersey Eisteddfod.

In Ireland, Seachtain na Gaeilge is similar to an eisteddfod; it celebrates Irish music and culture and promotes the use of the Irish language.

The "Fleadh" is an annual traditional music festival that takes place in the same town for a few years in a row, then moving on to another area of the country in an effort to include all localities in the celebration.

Eisteddfod outside Wales

Welsh emigration, particularly during the heyday of the British Empire and British industrial revolution[5], led to the foundation of formal and informal Welsh communities internationally. Among the traditions that travelled with these emigrees was the eisteddfod, some of which - in a variety of forms and languages - still exist.

United Kingdom

Eisteddfodau are held across the UK, though in most cases any explicit link to specifically Welsh culture has been lost beyond the use of the name for an arts festival or competition.

In 1897 a Forest of Dean Eisteddfod, reportedly a choral competition, was founded at Cinderford[6]. This annual event was still running in the 1940s.[7]

In the Methodist Church and other non-conformist denominations in England, youth cultural festivals are sometimes called eisteddfod. The Kettering and District Eisteddfod, for example, was founded in the Northamptonshire town by members of the Sunday School Union, and still runs every March.[8]

For many years Teignmouth Grammar School in Teignmouth, Devon held an eisteddfod of art, music and drama competitions in the Easter term.[9]

The Bristol Festival of Music, Speech and Drama was founded in 1903 as the Bristol Eisteddfod,[10] and the name still survives in the Bristol Dance Eisteddfod.[11]

Argentina

Eisteddfodau have been held since the initial Welsh settlement in Argentina in the late 19th century. Competitions nowadays are bilingual, in Welsh and Spanish, and include poetry and prose, translations (Welsh, Spanish, English, Italian, and French), musical performances, arts, folk dances, photography and video among others. A youth eisteddfod is held in Gaiman every September, and the main Chubut Eisteddfod is held in Trelew in October. An annual eisteddfod is also held in Trevelin, in the Andes and Puerto Madryn[citation needed] on the coast.[12]

Australia

Eisteddfods (Australian plural) have also been adopted into Australian culture. Much like the Welsh original, eisteddfods are competitions that involve testing individuals in singing, dancing, acting and musicianship. The Royal South Street Eisteddfod in Ballarat has been running since 1891.[13] At least 20 years earlier, as described in the diaries of Joseph Jenkins, Ballarat's Welsh community was conducting an annual eisteddfod each St David's Day (1 March). The Sydney Eisteddfod commenced in 1933 and offers some 400 events across all performing arts, catering to 30,000 performers annually. Modern equivalents in Australia are competitions reserved for schoolchildren, though many have open sections where anyone (including professionals) may participate and compete. Typically, a prize may be a scholarship to pursue a further career. Many young Australian actors and dancers participate regularly in the various competitions scheduled throughout the year. Many other communities host eisteddfods, including Alice Springs, Darwin, Brisbane and Melbourne.

South Africa

A number of international performing arts competitions in South Africa are called eisteddfods, such as the Tygerberg International Eisteddfod and the Pretoria Eisteddfod (first held in 1923). The word "eisteddfod" is sometimes also used by schools for ordinary cultural festivals, even if only one school's students participate.

United States

Moving first as religious dissenters and then as industrial workers, many thousands of Welsh people emigrated to America from the 17th century. By 1851, Y Drych ('The Mirror') was just the latest of a number of Welsh-language newspapers, and in 1872 Hanes Cymry America ("A history of the Welsh in America") by R.D. Thomas attempted to catalogue all of the Welsh communities of the United States. Eisteddfods in North America are thought to have started in the 1830s[14] though the earliest documented examples date from the 1850s.

The largest US eisteddfod was held In 1893 at the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago[15], featuring visiting Welsh choirs invited by The Cymmrodorion Society of Chicago.[16]The Mormon Tabernacle Choir, which included a large number of Welsh immigrants, made its first appearance outside of Utah at this event.[17] The eisteddfod idea was retained by some subsequent world's fairs, and helped to link the Welsh Eisteddfod community to its American offshoot. By 1913, a sub-Gorsedd of North America with a Vice-Archdruid, Thomas Edwards (bardic name, Cynonfardd), was established at the Pittsburgh Eisteddfod, surviving until 1946. [18]

On 28 July 1915, the International Eisteddfod held in San Francisco at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition drew competing choirs from around the nation, including one mixed group composed of the German members of the Metropolitan Opera Chorus from New York. The tightly-rehearsed, all-male Orpheus Club of Los Angeles was judged the winner and was awarded $3,000.[19]

In 1926, the Pasadena Playhouse in California, held a competitive eisteddfod of one-act plays by local authors that subsequently evolved into an annual Summer One-Act Play Festival.

Some smaller, regional eisteddfodau have deep historical roots. These include the Cynonfardd Eisteddfod in Edwardsville, Pennsylvania, which is the longest running eisteddfod outside Wales, with its 128th appearance in 2017[20] at the Dr. Edwards Memorial Church. The Jackson School Eisteddfod in Jackson, Ohio Is the result of an historically strong Welsh business community, who funded the Southern Ohio Eisteddfod Association and a 4,000-seater auditorium that was the only dedicated eisteddfod venue in the United States. In 1930, the hall hosted the Grand National Eisteddfod. While economic decline halted the adult events, a youth festival, founded in 1924, still runs today, with support from the Madog Center for Welsh Studies at University of Rio Grande.[21][22]

In the 21st century the Internet and social media helped new eisteddfodau to spring up. The West Coast Eisteddfod (originally the Left Coast Eisteddfod) was founded by Welsh-American social network AmeriCymru and the non-profit Portland, Oregon Meriwether Lewis Memorial Eisteddfod Foundation in 2009. [23] The 2011 event was held at the Barnsdall Art Park in Los Angeles, the site of Welsh-American architect Frank Lloyd Wright's Hollyhock House, near Griffith Park, founded by Welsh-American philanthropist Griffith J. Griffith.[24] AmeriCymru hosts an annual online eisteddfod. [25]

Welsh Heritage Week [26] Cwrs Cymraeg,[27] two ambulatory Welsh language and culture courses held annually usually in the United States, also feature a mini-Eisteddfod. The North American Festival of Wales held by the Welsh North American Association also holds includes an eisteddfod.[28]

See also

- Celtic festivals

- List of Celtic festivals

References

^ Harper, Douglas (2001–2011). "Eisteddfod". Online Etymological Dictionary. Retrieved 18 October 2011..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Williams, Sian. "Druids, bards and rituals: What is an Eisteddfod?". BBC. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

^ Berry, Oliver; Else, David; Atkinson, David (2010). Discover Great Britain. Lonely Planet. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-74179-993-4.

^ Urdd Gobaith Cymru. "Urdd Gobaith Cymru". Archived from the original on 28 April 2006. Retrieved 31 January 2007.

^ "Working Abroad - Welsh Emigration". National Museum Wales. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

^ "Forest of Dean: Social life | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

^ "Forest Eisteddford - Forum". www.forest-of-dean.net. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

^ Warwick. "About the Eisteddfod". www.ketteringeisteddfod.org.uk. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

^ "TOGA : Home page". www.toga.org.uk. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

^ "Bristol Festival of Music, Speech & Drama 2017".

^ http://www.bristoldance.co.uk/

^ Brooks, Walter Ariel. "Eisteddfod: La cumbre de la poesía céltica". Sitio al Margen. Retrieved 4 October 2006.

^ "Welcome - Royal South Street Society". Archived from the original on 26 April 2007.

^ Parry, Gerri. "Festival Program". www.nafow.org. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

^ Nicholls, David (1998-11-19). The Cambridge History of American Music. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521454292.

^ "Cynon Culture - Welsh Eisteddfod At Chicago". www.cynonculture.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

^ Linda Louise Pohly, "Welsh Choral Music in America in the Nineteenth Century,"

PhD dissertation, Ohio State University, 1989,72.

^ "Celtic and other Gorseddau". National Museum Wales. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

^ Musical America, 7 August 1915, p. 4.

^ "Dr Edwards Memorial Church". Dr Edwards Memorial Church. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

^ DiBari, Sherry. "Jackson Eisteddfod".

^ "Jackson City Schools Eisteddfod Program". www.rio.edu. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

^ "Meriwether Lewis Memorial Eisteddfod Foundation". Meriwether Lewis Memorial Eisteddfod Foundation. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

^ "The British Weekly – West Coast Eisteddfod slated for Barnsdall Art Park".

^ "AmeriCymru.net". AmeriCymru social network. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

^ WHW

^ "Croeso I Wefan Cymdeithas Madog".

^ Parry, Gerri. "WNAA - NAFOW Home".

External links

| Look up eisteddfod in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eisteddfodau. |

National Eisteddfod Festival website (in Welsh) and (in English)

Llangollen International Eisteddfod website