Natural History Museum, Berlin

| |

| Established | 1810 |

|---|---|

| Location | Invalidenstraße 43 10115 Berlin, Germany |

| Coordinates | 52°31′48″N 13°22′46″E / 52.530020°N 13.379514°E / 52.530020; 13.379514Coordinates: 52°31′48″N 13°22′46″E / 52.530020°N 13.379514°E / 52.530020; 13.379514 |

| Type | Natural history museum |

| Director | Johannes Vogel |

| Website | http://www.naturkundemuseum.berlin/en |

The Natural History Museum (in German: Museum für Naturkunde) is a natural history museum located in Berlin, Germany. It exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history and in such domain it is one of three major museums in Germany alongside Naturmuseum Senckenberg in Frankfurt and Museum Koenig in Bonn. German speakers mainly call this museum Museum für Naturkunde since this is the term that can be read in the façade's Museum. It is also called Naturkundemuseum or even Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin so that it can be distinguished from other museums in Germany also named as Museum für Naturkunde. The museum's official name changed through time. It had been originally founded in 1810 as a part of the Berlin University, which changed its name to Humboldt University of Berlin in 1949. This is why the Natural History Museum in Berlin had been known for a long part of its history as the "Humboldt Museum",[1] but in 2009 it left the university to join the Leibniz Association. The current official name is Museum für Naturkunde – Leibniz-Institut für Evolutions- und Biodiversitätsforschung and the "Humboldt" name is no longer related to this museum. Furthermore: there is another Humboldt-Museum in Berlin in Tegel Palace dealing with brothers Wilhelm and Alexander von Humboldt.

The museum houses more than 30 million zoological, paleontological, and mineralogical specimens, including more than ten thousand type specimens. It is famous for two exhibits: the largest mounted dinosaur in the world (a Giraffatitan skeleton), and a well-preserved specimen of the earliest known bird, Archaeopteryx. The museum's mineral collections date back to the Prussian Academy of Sciences of 1700. Important historic zoological specimens include those recovered by the German deep-sea Valdiva expedition (1898–99), the German Southpolar Expedition (1901–03), and the German Sunda Expedition (1929–31). Expeditions to fossil beds in Tendaguru in former Deutsch Ostafrika (today Tanzania) unearthed rich paleontological treasures. The collections are so extensive that less than 1 in 5000 specimens is exhibited, and they attract researchers from around the world. Additional exhibits include a mineral collection representing 75% of the minerals in the world, a large meteor collection, the largest piece of amber in the world; exhibits of the now-extinct quagga, huia, and tasmanian tiger, and "Bobby" the gorilla, a Berlin Zoo celebrity from the 1920s and 1930s.

In November 2018 the german government and the city of Berlin decided to expand and improve the building for more than 600 million €.[2]

Contents

1 Exhibitions

1.1 Dinosaur Hall

1.1.1 Archaeopteryx

1.2 Minerals Halls

1.3 Evolution in action

1.4 Tristan – Berlin bares teeth

2 History

3 See also

4 References

5 Further reading

6 External links

Exhibitions

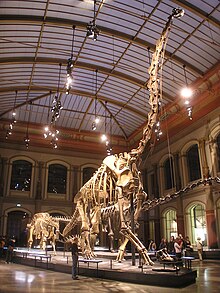

The Dinosaur Hall seen from the entrance, with the skeleton of Giraffatitan (formerly Brachiosaurus) brancai in the center

The 'Berlin Specimen' of Archaeopteryx

Since the museum renovation in 2007, a large hall explains biodiversity and the processes of evolution, while several rooms feature regularly changing special exhibitions.

Dinosaur Hall

The specimen of Giraffatitan brancai[3] in the central exhibit hall is the largest mounted dinosaur skeleton in the world.

It is composed of fossilized bones recovered by the German paleontologist Werner Janensch from the fossil-rich Tendaguru beds of Tanzania between 1909 and 1913. The remains are primarily from one gigantic animal, except for a few tail bones (caudal vertebrae), which belong to another animal of the same size and species.

The historical mount (until about 2005) was 12.72 m (41 ft 5 in) tall, and 22.25 m (73 ft) long. In 2007 it was remounted according to new scientific evidence, reaching a height of 13.27 m. When living, the long-tailed, long-necked herbivore probably weighed 50 t (55 tons). While the Diplodocus carnegiei mounted next to it (a copy of an original from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, United States) actually exceeds it in length (27 m, or 90 ft), the Berlin specimen is taller, and far more massive.

The Dinosaur hall, reverse view. Kentrosaurus in the foreground, Diplodocus, Giraffatitan and Dicraeosaurus from left to right in the back.

Archaeopteryx

The "Berlin Specimen" of Archaeopteryx lithographica (HMN 1880), is displayed in the central exhibit hall. The dinosaur-like body with an attached tooth-filled head, wings, claws, long lizard-like tail, and the clear impression of feathers in the surrounding stone is strong evidence of the link between reptiles and birds. The Archaeopteryx is a transitional fossil; and the time of its discovery was apt: coming on the heels of Darwin's 1859 magnum opus, The Origin of Species, made it quite possibly the most famous fossil in the world.

Recovered from the German Solnhofen limestone beds in 1871, it is only the third Archaeopteryx to be discovered and the most complete. The first specimen, a single 150-million-year-old feather found in 1860, is also in the possession of the museum.

Minerals Halls

The MFN's collection comprises roughly 250,000 specimens of minerals, of which roughly 4,500 are on exhibit in the Hall of Minerals.[4][5]

Evolution in action

A large hall explains the principles of evolution. It was opened in 2007 after a major renovation of parts of the building.

Tristan – Berlin bares teeth

"Tristan", a Tyrannosaurus rex

The Museum für Naturkunde now exhibits one of the best-preserved Tyrannosaurus skeletons ("Tristan") worldwide. Of approximately 300 bones, 170 have been preserved, which puts it in the third position among others.[6]

History

Collection of minerals

A dodo model

Bao Bao the Giant Panda that lived at the Berlin Zoo

Knut (polar bear): the Polar Bear that lived at the Berlin Zoo

Minerals in the museum were originally part of the collection of instructors from the Berlin Mining Academy. The University of Berlin was founded in 1810, and acquired the first of these collections in 1814, under the aegis of the new Museum of Mineralogy. In 1857, the paleontology department was founded, and 1854 a department of petrography and general geology was added.

By 1886 the university was overflowing with collections, so design began on a new building nearby at Invalidenstraße 43, which opened as the Museum für Naturkunde (Natural History Museum) in 1889. The museum was built on the site of a former ironworks and this is reflected in two spectacular cast iron stairwells within the building.

Of particular significance is the contribution of the first director after the move to the new building. In the past the museum simply consisted of the entire collections being open to the public, but Karl Möbius instigated a clear split between a public exhibition space with a few choice specimens, together with explanations of their relevance, and the remainder of the collection held in archives for scientific study.

The collections were damaged by the Allied bombing of Berlin during World War II. The eastern wing was severely damaged, and was rebuilt only in 2011, now housing the alcohol collections (partly publicly accessible).

In 1993, after the shake-up caused by the reunification of Germany, the museum split into the three divisions: The Institutes of Mineralogy, Zoology, and Paleontology. Infighting between the institute directors led to important changes in 2006, which saw the appointment of a Director General and the replacement of the former institutes by a division into Collections, Research and Exhibitions. Since January 1, 2009 the Museum has officially separated from the Humboldt-University and became part of the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Scientific Community as the Museum für Naturkunde – Leibniz Institute for Evolutionary and Biodiversity Research at the Humboldt University, Berlin (German: Museum für Naturkunde – Leibniz-Institut für Evolutions- und Biodiversitätsforschung an der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin). It is legally set up as a foundation.

See also

- List of museums in Germany

- List of natural history museums

Biodiversity Heritage Library for Europe (Museum für Naturkunde is a lead institution)

Zoosystematics and Evolution and Deutsche Entomologische Zeitschrift (scholarly journals associated with the Museum)

References

^ See page 19: "MB: Berlin Museum für Naturkunde (formerly Humboldt Museum für Naturkunde)" in Kenneth Carpenter, Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs, Indiana University Press, 384 pages, 2006, .mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

ISBN 978-0-253-34817-3

^ Sentker, Andreas. "Ideen für das Überleben der Menschheit". 2018-11-14 (in German). Retrieved 2018-11-18.

^ Gregory S. Paul formally moved the Brachiosaurus brancai species to a new subgenus (Giraffatitan) in 1988, and George Olshevsky promoted the new taxa to genus in 1991. Although the change has been generally accepted among scientists, as of 2015 the museum's labels still use the old genus name.

^ Süddeutsche Zeitung Online Wissenschaft im Paradies - Schöner forschen, accessed 9.9.2011

^ MFN entry in the database University museums and collections in Germany of the Hermann von Helmholtz-Zentrums für Kulturtechnik, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Archived 2011-09-03 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 9.9.2011

^ Tristan exhibition Tristan – Berlin bares teeth, accessed 4.2.2017

Further reading

Olshevsky, G. (1991). "A Revision of the Parainfraclass Archosauria Cope, 1869, Excluding the Advanced Crocodylia". Mesozoic Meanderings #2. 1 (4): 196 pp.

Paul, G. S. (1988). "The brachiosaur giants of the Morrison and Tendaguru with a description of a new subgenus, Giraffatitan, and a comparison of the world's largest dinosaurs". Hunteria. 2 (3): 1–14.

- Maier, Gerhard. African dinosaurs unearthed: the Tendaguru expeditions. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2003. (Life of the Past Series).

- Damaschun, F., Böhme, G. & H. Landsberg, 2000. Naturkundliche Museen der Berliner Universität – Museum für Naturkunde: 190 Jahre Sammeln und Forschen. 86-106.— In: H. Bredekamp, J. Brüning & C. Weber (eds.). Theater der Natur und Kunst Theatrum Naturae et Artis. Essays Wunderkammern des Wissens, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin & Henschel Verlag. 1-280. Berlin.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. |

Museum für Naturkunde (home page)- History of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

- History of the mineralogical collections at the Natural History Museum in Berlin

- History of the mineral collection