Cone cell

| Cone cells | |

|---|---|

Normalized responsivity spectra of human cone cells, S, M, and L types | |

| Details | |

| Location | Retina of mammals |

| Function | Color vision |

| Identifiers | |

NeuroLex ID | sao1103104164 |

| TH | H3.11.08.3.01046 |

Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy [edit on Wikidata] | |

Cone cells, or cones, are photoreceptor cells in the retinas of vertebrate eyes (e.g. the human eye). They respond differently to light of different wavelengths, and are thus responsible for color vision and function best in relatively bright light, as opposed to rod cells, which work better in dim light. Cone cells are densely packed in the fovea centralis, a 0.3 mm diameter rod-free area with very thin, densely packed cones which quickly reduce in number towards the periphery of the retina. There are about six to seven million cones in a human eye and are most concentrated towards the macula.[1]

The commonly cited figure of six million cone cells in the human eye was found by Osterberg in 1935.[2] Oyster's textbook (1999)[3] cites work by Curcio et al. (1990) indicating an average close to 4.5 million cone cells and 90 million rod cells in the human retina.[4]

Cones are less sensitive to light than the rod cells in the retina (which support vision at low light levels), but allow the perception of color. They are also able to perceive finer detail and more rapid changes in images, because their response times to stimuli are faster than those of rods.[5] Cones are normally one of the three types, each with different pigment, namely: S-cones, M-cones and L-cones. Each cone is therefore sensitive to visible wavelengths of light that correspond to short-wavelength, medium-wavelength and long-wavelength light.[6] Because humans usually have three kinds of cones with different photopsins, which have different response curves and thus respond to variation in color in different ways, we have trichromatic vision. Being color blind can change this, and there have been some verified reports of people with four or more types of cones, giving them tetrachromatic vision.[7][8][9]

The three pigments responsible for detecting light have been shown to vary in their exact chemical composition due to genetic mutation; different individuals will have cones with different color sensitivity.

Contents

1 Structure

1.1 Types

1.2 Shape and arrangement

2 Function

2.1 Color afterimage

3 Clinical significance

4 See also

5 References

6 External links

Structure

Types

Humans normally have three types of cones. The first responds the most to light of long wavelengths, peaking at about 560 nm; this type is sometimes designated L for long. The second type responds the most to light of medium-wavelength, peaking at 530 nm, and is abbreviated M for medium. The third type responds the most to short-wavelength light, peaking at 420 nm, and is designated S for short. The three types have peak wavelengths near 564–580 nm, 534–545 nm, and 420–440 nm, respectively, depending on the individual.[10][11]

While it has been discovered that there exists a mixed type of bipolar cells that bind to both rod and cone cells, bipolar cells still predominantly receive their input from cone cells.[12]

Shape and arrangement

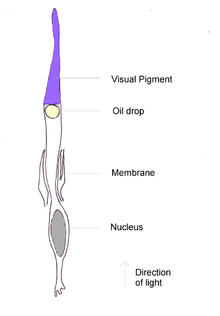

Cone cell structure

Cone cells are somewhat shorter than rods, but wider and tapered, and are much less numerous than rods in most parts of the retina, but greatly outnumber rods in the fovea. Structurally, cone cells have a cone-like shape at one end where a pigment filters incoming light, giving them their different response curves. They are typically 40–50 µm long, and their diameter varies from 0.5 to 4.0 µm, being smallest and most tightly packed at the center of the eye at the fovea. The S cone spacing is slightly larger than the others.[13]

Photobleaching can be used to determine cone arrangement. This is done by exposing dark-adapted retina to a certain wavelength of light that paralyzes the particular type of cone sensitive to that wavelength for up to thirty minutes from being able to dark-adapt making it appear white in contrast to the grey dark-adapted cones when a picture of the retina is taken. The results illustrate that S cones are randomly placed and appear much less frequently than the M and L cones. The ratio of M and L cones varies greatly among different people with regular vision (e.g. values of 75.8% L with 20.0% M versus 50.6% L with 44.2% M in two male subjects).[14]

Like rods, each cone cell has a synaptic terminal, an inner segment, and an outer segment as well as an interior nucleus and various mitochondria. The synaptic terminal forms a synapse with a neuron such as a bipolar cell. The inner and outer segments are connected by a cilium.[5] The inner segment contains organelles and the cell's nucleus, while the outer segment, which is pointed toward the back of the eye, contains the light-absorbing materials.[5]

Unlike rods, the outer segments of cones have invaginations of their cell membranes that create stacks of membranous disks. Photopigments exist as transmembrane proteins within these disks, which provide more surface area for light to affect the pigments. In cones, these disks are attached to the outer membrane, whereas they are pinched off and exist separately in rods. Neither rods nor cones divide, but their membranous disks wear out and are worn off at the end of the outer segment, to be consumed and recycled by phagocytic cells.

Function

Bird, reptilian, and monotreme cone cells

The difference in the signals received from the three cone types allows the brain to perceive a continuous range of colors, through the opponent process of color vision. (Rod cells have a peak sensitivity at 498 nm, roughly halfway between the peak sensitivities of the S and M cones.)

All of the receptors contain the protein photopsin, with variations in its conformation causing differences in the optimum wavelengths absorbed.

The color yellow, for example, is perceived when the L cones are stimulated slightly more than the M cones, and the color red is perceived when the L cones are stimulated significantly more than the M cones. Similarly, blue and violet hues are perceived when the S receptor is stimulated more. Cones are most sensitive to light at wavelengths around 420 nm. However, the lens and cornea of the human eye are increasingly absorptive to shorter wavelengths, and this sets the short wavelength limit of human-visible light to approximately 380 nm, which is therefore called 'ultraviolet' light. People with aphakia, a condition where the eye lacks a lens, sometimes report the ability to see into the ultraviolet range.[15] At moderate to bright light levels where the cones function, the eye is more sensitive to yellowish-green light than other colors because this stimulates the two most common (M and L) of the three kinds of cones almost equally. At lower light levels, where only the rod cells function, the sensitivity is greatest at a blueish-green wavelength.

Cones also tend to possess a significantly elevated visual acuity because each cone cell has a lone connection to the optic nerve, therefore, the cones have an easier time telling that two stimuli are isolated. Separate connectivity is established in the

inner plexiform layer so that each connection is parallel.[12]

The response of cone cells to light is also directionally nonuniform, peaking at a direction that receives light from the center of the pupil; this effect is known as the Stiles–Crawford effect.

Color afterimage

Sensitivity to a prolonged stimulation tends to decline over time, leading to neural adaptation. An interesting effect occurs when staring at a particular color for a minute or so. Such action leads to an exhaustion of the cone cells that respond to that color – resulting in the afterimage. This vivid color aftereffect can last for a minute or more.[16]

Clinical significance

One of the diseases related to cone cells present in retina is retinoblastoma. Retinoblastoma is a rare cancer of the retina, caused by the mutation of both copies of retinoblastoma genes (RB1). Most cases of retinoblastoma occur during early childhood.[17] One or both eyes may be affected. The protein encoded by RB1 regulates a signal transduction pathway while controlling the cell cycle progression as normally. Retinoblastoma seems to originate in cone precursor cells present in the retina that consist of natural signalling networks which restrict cell death and promote cell survival after losing the RB1, or having both the RB1 copies mutated. It has been found that TRβ2 which is a transcription factor specifically affiliated with cones is essential for rapid reproduction and existence of the retinoblastoma cell.[17] A drug that can be useful in the treatment of this disease is MDM2 (murine double minute 2) gene. Knockdown studies have shown that the MDM2 gene silences ARF-induced apoptosis in retinoblastoma cells and that MDM2 is necessary for the survival of cone cells.[17]

It is unclear at this point why the retinoblastoma in humans is sensitive to RB1 inactivation.

The pupil may appear white or have white spots. A white glow in the eye is often seen in photographs taken with a flash, instead of the typical "red eye" from the flash, and the pupil may appear white or distorted. Other symptoms can include crossed eyes, double vision, eyes that do not align, eye pain and redness, poor vision or differing iris colors in each eye. If the cancer has spread, bone pain and other symptoms may occur.[17][18]

See also

- Cone dystrophy

- Disc shedding

- Double cones

- RG color space

- Tetrachromacy

- Melanopsin

References

^ "The Rods and Cones of the Human Eye"..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Osterberg, G. (1935). "Topography of the layer of rods and cones in the human retina". Acta Ophthalmol. Suppl. 13 (6): 1–102.

^ Oyster, C. W. (1999). The human eye: structure and function. Sinauer Associates.

^ Curcio, CA.; Sloan, KR.; Kalina, RE.; Hendrickson, AE. (Feb 1990). "Human photoreceptor topography". J Comp Neurol. 292 (4): 497–523. doi:10.1002/cne.902920402. PMID 2324310.

^ abc Kandel, E.R.; Schwartz, J.H; Jessell, T. M. (2000). Principles of Neural Science (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 507–513.

^ Schacter, Gilbert, Wegner, "Psychology", New York: Worth Publishers,2009.

^

Jameson, K. A.; Highnote, S. M. & Wasserman, L. M. (2001). "Richer color experience in observers with multiple photopigment opsin genes" (PDF). Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 8 (2): 244–261. doi:10.3758/BF03196159. PMID 11495112.

^

"You won't believe your eyes: The mysteries of sight revealed". The Independent. 7 March 2007.

^

Mark Roth (September 13, 2006). "Some women may see 100,000,000 colors, thanks to their genes". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

^ Wyszecki, Günther; Stiles, W.S. (1981). Color Science: Concepts and Methods, Quantitative Data and Formulae (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley Series in Pure and Applied Optics. ISBN 978-0-471-02106-3.

^ R. W. G. Hunt (2004). The Reproduction of Colour (6th ed.). Chichester UK: Wiley–IS&T Series in Imaging Science and Technology. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-470-02425-6.

^ ab Strettoi, E; Novelli, E; Mazzoni, F; Barone, I; Damiani, D (Jul 2010). "Complexity of retinal cone bipolar cells". Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 29 (4): 272–83. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.03.005. PMC 2878852. PMID 20362067.

^ Brian A. Wandel (1995). "Foundations of Vision".

^ Roorda A.; Williams D.R. (1999). "The arrangement of the three cone classes in the living human eye". Nature. 397 (6719): 520–522. doi:10.1038/17383. PMID 10028967.

^ Let the light shine in: You don't have to come from another planet to see ultraviolet light EducationGuardian.co.uk, David Hambling (May 30, 2002)

^ Schacter, Daniel L. Psychology: the second edition. Chapter 4.9.

^ abcd Skinner, Mhairi (2009). "Tumorigenesis: Cone cells set the stage". Nature Reviews Cancer. 9 (8): 534. doi:10.1038/nrc2710.

^ "Retinoblastoma". A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. Missing or empty|url=(help)

External links

- Cell Centered Database – Cone cell

- Webvision's Photoreceptors

NIF Search – Cone Cell via the Neuroscience Information Framework- Model and image of cone cell