Literature

| Literature |

|---|

|

Major forms |

|

Genres |

|

Media |

|

Techniques |

|

History and lists |

|

Discussion |

|

Literature, most generically, is any body of written works. More restrictively, literature refers to writing considered to be an art form or any single writing deemed to have artistic or intellectual value, often due to deploying language in ways that differ from ordinary usage.

Its Latin root literatura/litteratura (derived itself from littera: letter or handwriting) was used to refer to all written accounts. The concept has changed meaning over time to include texts that are spoken or sung (oral literature), and non-written verbal art forms. Developments in print technology have allowed an ever-growing distribution and proliferation of written works, culminating in electronic literature.

Literature is classified according to whether it is fiction or non-fiction, and whether it is poetry or prose. It can be further distinguished according to major forms such as the novel, short story or drama; and works are often categorized according to historical periods or their adherence to certain aesthetic features or expectations (genre).

Contents

1 Definitions

1.1 Genres

2 History

3 Psychology and literature

4 Poetry

5 Prose

5.1 Fiction

5.1.1 Novel

5.1.2 Novella

5.1.3 Short story

5.2 Essays

5.3 Natural science

5.4 Philosophy

5.5 History

5.6 Law

6 Drama

7 Other narrative forms

8 Literary techniques

9 Legal status

9.1 United Kingdom

10 Awards

11 See also

12 Notes

13 References

14 Further reading

15 External links

Definitions

Definitions of literature have varied over time: it is a "culturally relative definition".[1] In Western Europe prior to the 18th century, literature denoted all books and writing.[1] A more restricted sense of the term emerged during the Romantic period, in which it began to demarcate "imaginative" writing.[2][3] Contemporary debates over what constitutes literature can be seen as returning to older, more inclusive notions; Cultural studies, for instance, takes as its subject of analysis both popular and minority genres, in addition to canonical works.

The value judgment definition of literature considers it to cover exclusively those writings that possess high quality or distinction, forming part of the so-called belles-lettres ('fine writing') tradition.[4] This sort of definition is that used in the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition (1910–11) when it classifies literature as "the best expression of the best thought reduced to writing."[5] Problematic in this view is that there is no objective definition of what constitutes "literature": anything can be literature, and anything which is universally regarded as literature has the potential to be excluded, since value judgments can change over time.[4]

The formalist definition is that "literature" foregrounds poetic effects; it is the "literariness" or "poetic" of literature that distinguishes it from ordinary speech or other kinds of writing (e.g., journalism).[6][7] Jim Meyer considers this a useful characteristic in explaining the use of the term to mean published material in a particular field (e.g., "scientific literature"), as such writing must use language according to particular standards.[8] The problem with the formalist definition is that in order to say that literature deviates from ordinary uses of language, those uses must first be identified; this is difficult because "ordinary language" is an unstable category, differing according to social categories and across history.[9]

Etymologically, the term derives from Latin literatura/litteratura "learning, a writing, grammar," originally "writing formed with letters," from litera/littera "letter".[10] In spite of this, the term has also been applied to spoken or sung texts.[8][11]

Genres

Literary genre is a mode of categorizing literature. A French term for "a literary type or class".[12] However, such classes are subject to change, and have been used in different ways in different periods and traditions.

History

Egyptian hieroglyphs with cartouches for the name "Ramesses II", from the Luxor Temple, New Kingdom

The history of literature follows closely the development of civilization. When defined exclusively as written work, Ancient Egyptian literature,[13] along with Sumerian literature, are considered the world's oldest literatures.[14] The primary genres of the literature of Ancient Egypt—didactic texts, hymns and prayers, and tales—were written almost entirely in verse;[15] while use of poetic devices is clearly recognizable, the prosody of the verse is unknown.[16][17] Most Sumerian literature is apparently poetry,[18][19] as it is written in left-justified lines,[20] and could contain line-based organization such as the couplet or the stanza,[21]

Different historical periods are reflected in literature. National and tribal sagas, accounts of the origin of the world and of customs, and myths which sometimes carry moral or spiritual messages predominate in the pre-urban eras. The epics of Homer, dating from the early to middle Iron age, and the great Indian epics of a slightly later period, have more evidence of deliberate literary authorship, surviving like the older myths through oral tradition for long periods before being written down.

Literature in all its forms can be seen as written records, whether the literature itself be factual or fictional, it is still quite possible to decipher facts through things like characters' actions and words or the authors' style of writing and the intent behind the words. The plot is for more than just entertainment purposes; within it lies information about economics, psychology, science, religions, politics, cultures, and social depth. Studying and analyzing literature becomes very important in terms of learning about human history. Literature provides insights about how society has evolved and about the societal norms during each of the different periods all throughout history. For instance, postmodern authors argue that history and fiction both constitute systems of signification by which we make sense of the past.[22] It is asserted that both of these are "discourses, human constructs, signifying systems, and both derive their major claim to truth from that identity."[22] Literature provides views of life, which is crucial in obtaining truth and in understanding human life throughout history and its periods.[23] Specifically, it explores the possibilities of living in terms of certain values under given social and historical circumstances.[23]

Literature helps us understand references made in more modern literature because authors often reference mythology and other old religious texts to describe ancient civilizations such as the Hellenes and the Egyptians.[24] Not only is there literature written on each of the aforementioned topics themselves, and how they have evolved throughout history (like a book about the history of economics or a book about evolution and science, for example) but one can also learn about these things in fictional works. Authors often include historical moments in their works, like when Lord Byron talks about the Spanish and the French in "Childe Harold's Pilgrimage: Canto I"[25] and expresses his opinions through his character Childe Harold. Through literature we are able to continuously uncover new information about history. It is easy to see how all academic fields have roots in literature.[26] Information became easier to pass down from generation to generation once we began to write it down. Eventually everything was written down, from things like home remedies and cures for illness, or how to build shelter to traditions and religious practices. From there people were able to study literature, improve on ideas, further our knowledge, and academic fields such as the medical field or trades could be started. In much the same way as the literature that we study today continue to be updated as we[who?] continue to evolve and learn more and more.

As a more urban culture developed, academies provided a means of transmission for speculative and philosophical literature in early civilizations, resulting in the prevalence of literature in Ancient China, Ancient India, Persia and Ancient Greece and Rome. Many works of earlier periods, even in narrative form, had a covert moral or didactic purpose, such as the Sanskrit Panchatantra or the Metamorphoses of Ovid. Drama and satire also developed as urban culture provided a larger public audience, and later readership, for literary production. Lyric poetry (as opposed to epic poetry) was often the speciality of courts and aristocratic circles, particularly in East Asia where songs were collected by the Chinese aristocracy as poems, the most notable being the Shijing or Book of Songs. Over a long period, the poetry of popular pre-literate balladry and song interpenetrated and eventually influenced poetry in the literary medium.

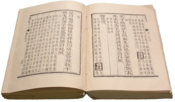

In ancient China, early literature was primarily focused on philosophy, historiography, military science, agriculture, and poetry. China, the origin of modern paper making and woodblock printing, produced the world's first print cultures.[27] Much of Chinese literature originates with the Hundred Schools of Thought period that occurred during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (769‒269 BCE). The most important of these include the Classics of Confucianism, of Daoism, of Mohism, of Legalism, as well as works of military science (e.g. Sun Tzu's The Art of War) and Chinese history (e.g. Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian). Ancient Chinese literature had a heavy emphasis on historiography, with often very detailed court records. An exemplary piece of narrative history of ancient China was the Zuo Zhuan, which was compiled no later than 389 BCE, and attributed to the blind 5th-century BCE historian Zuo Qiuming.

In ancient India, literature originated from stories that were originally orally transmitted. Early genres included drama, fables, sutras and epic poetry. Sanskrit literature begins with the Vedas, dating back to 1500–1000 BCE, and continues with the Sanskrit Epics of Iron Age India. The Vedas are among the oldest sacred texts. The Samhitas (vedic collections) date to roughly 1500–1000 BCE, and the "circum-Vedic" texts, as well as the redaction of the Samhitas, date to c. 1000‒500 BCE, resulting in a Vedic period, spanning the mid-2nd to mid 1st millennium BCE, or the Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age.[28] The period between approximately the 6th to 1st centuries BCE saw the composition and redaction of the two most influential Indian epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, with subsequent redaction progressing down to the 4th century AD. Other major literary works are Ramcharitmanas & Krishnacharitmanas.

In ancient Greece, the epics of Homer, who wrote the Iliad and the Odyssey, and Hesiod, who wrote Works and Days and Theogony, are some of the earliest, and most influential, of Ancient Greek literature. Classical Greek genres included philosophy, poetry, historiography, comedies and dramas. Plato and Aristotle authored philosophical texts that are the foundation of Western philosophy, Sappho and Pindar were influential lyric poets, and Herodotus and Thucydides were early Greek historians. Although drama was popular in Ancient Greece, of the hundreds of tragedies written and performed during the classical age, only a limited number of plays by three authors still exist: Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. The plays of Aristophanes provide the only real examples of a genre of comic drama known as Old Comedy, the earliest form of Greek Comedy, and are in fact used to define the genre.[29]

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, one of the most prolific German writers

Roman histories and biographies anticipated the extensive mediaeval literature of lives of saints and miraculous chronicles, but the most characteristic form of the Middle Ages was the romance, an adventurous and sometimes magical narrative with strong popular appeal. Controversial, religious, political and instructional literature proliferated during the Renaissance as a result of the invention of printing, while the mediaeval romance developed into a more character-based and psychological form of narrative, the novel, of which early and important examples are the Chinese Monkey and the German Faust books.

In the Age of Reason philosophical tracts and speculations on history and human nature integrated literature with social and political developments. The inevitable reaction was the explosion of Romanticism in the later 18th century which reclaimed the imaginative and fantastical bias of old romances and folk-literature and asserted the primacy of individual experience and emotion. But as the 19th century went on, European fiction evolved towards realism and naturalism, the meticulous documentation of real life and social trends. Much of the output of naturalism was implicitly polemical, and influenced social and political change, but 20th century fiction and drama moved back towards the subjective, emphasizing unconscious motivations and social and environmental pressures on the individual. Writers such as Proust, Eliot, Joyce, Kafka and Pirandello exemplify the trend of documenting internal rather than external realities.

Genre fiction also showed it could question reality in its 20th century forms, in spite of its fixed formulas, through the enquiries of the skeptical detective and the alternative realities of science fiction. The separation of "mainstream" and "genre" forms (including journalism) continued to blur during the period up to our own times. William Burroughs, in his early works, and Hunter S. Thompson expanded documentary reporting into strong subjective statements after the second World War, and post-modern critics have disparaged the idea of objective realism in general.

Psychology and literature

Theorists suggest that literature allows readers to access intimate emotional aspects of a person's character that would not be obvious otherwise.[30] That literature aids the psychological development and understanding of the reader, allowing someone to access emotional states from which they had distanced themselves. D. Mitchell, for example, explains how one author used young adult literature to describes a state of "wonder" she had experienced as a child.[31] There are also those who focus on the significance of literature in an individual's psychological development. For example, language learning uses literature because it articulates or contains culture, which is an element considered crucial in learning a language.[32] This is demonstrated in the case of a study that revealed how the presence of cultural values and culturally familiar passages in literary texts played an important impact on the performance of minority students in English reading.[33] Psychologists have also been using literature as a tool or therapeutic vehicle for people, to help them understand challenges and issues. An example is the integration of subliminal messages in literary texts or the rewriting of traditional narratives to help readers address their problems or mold them into contemporary social messages.[34][35]

Hogan also explains that the time and emotion which a person devotes to understanding a character's situation makes literature "ecological[ly] valid in the study of emotion".[36] That is literature unites a large community by provoking universal emotions, as well s allowing readers to access cultural aspects that they have not been exposed to, and that produce new emotional experiences.[37] Theorists argue that authors choose literary device according to what psychological emotion they are attempting to describe.[38]

Some psychologists regard literature as a valid research tool, because it allows them to discover new psychological ideas.[39] Psychological theories about literature, such as Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs have become universally recognized.

Psychologist Maslow's "Third Force Psychology Theory" helps literary analysts to critically understand how characters reflect the culture and the history to which they belong. It also allows them to understand the author's intention and psychology.[40] The theory suggests that human beings possess within them their true "self" and that the fulfillment of this is the reason for living. It also suggests that neurological development hinders actualizing this and a person becomes estranged from his or her true self.[41] Maslow argues that literature explores this struggle for self-fulfillment.[38] Paris in his "Third Force Psychology and the Study of Literature" argues that "D.H. Lawrence's 'pristine unconscious' is a metaphor for the real self".[42] Literature, it is here suggested, is therefore a tool that allows readers to develop and apply critical reasoning to the nature of emotions.

Poetry

A calligram by Guillaume Apollinaire. These are a type of poem in which the written words are arranged in such a way to produce a visual image.

Poetry is a form of literary art which uses the aesthetic qualities of language (including music, and rhythm) to evoke meanings beyond a prose paraphrase.[43] Poetry has traditionally been distinguished from prose by its being set in verse; prose is cast in sentences, poetry in lines; the syntax of prose is dictated by meaning, whereas that of poetry is held across meter or the visual aspects of the poem.[44][45] This distinction is complicated by various hybrid forms such as the prose poem[46] and prosimetrum,[47] and more generally by the fact that prose possesses rhythm.[48] Abram Lipsky refers to it as an "open secret" that "prose is not distinguished from poetry by lack of rhythm".[49]

Prior to the 19th century, poetry was commonly understood to be something set in metrical lines; accordingly, in 1658 a definition of poetry is "any kind of subject consisting of Rhythm or Verses".[43] Possibly as a result of Aristotle's influence (his Poetics), "poetry" before the 19th century was usually less a technical designation for verse than a normative category of fictive or rhetorical art.[50] As a form it may pre-date literacy, with the earliest works being composed within and sustained by an oral tradition;[51][52] hence it constitutes the earliest example of literature.

Prose

Prose is a form of language that possesses ordinary syntax and natural speech, rather than a regular metre; in which regard, along with its presentation in sentences rather than lines, it differs from most poetry.[44][45][53] However, developments in modern literature, including free verse and prose poetry have tended to blur any differences, and American poet T.S. Eliot suggested that while: "the distinction between verse and prose is clear, the distinction between poetry and prose is obscure".[54]

On the historical development of prose, Richard Graff notes that "[In the case of Ancient Greece] recent scholarship has emphasized the fact that formal prose was a comparatively late development, an "invention" properly associated with the classical period".[55]

Philosophical, historical, journalistic, and scientific writings are traditionally ranked as literature. They offer some of the oldest prose writings in existence; novels and prose stories earned the names "fiction" to distinguish them from factual writing or nonfiction, which writers historically have crafted in prose.

Fiction

Novel

A long fictional prose narrative. In English, the term emerged from the Romance languages in the late 15th century, with the meaning of "news"; it came to indicate something new, without a distinction between fact or fiction.[56] The romance is a closely related long prose narrative. Walter Scott defined it as "a fictitious narrative in prose or verse; the interest of which turns upon marvellous and uncommon incidents", whereas in the novel "the events are accommodated to the ordinary train of human events and the modern state of society".[57] Other European languages do not distinguish between romance and novel: "a novel is le roman, der Roman, il romanzo",[58] indicates the proximity of the forms.[59]

Although there are many historical prototypes, so-called "novels before the novel",[60] the modern novel form emerges late in cultural history—roughly during the eighteenth century.[61] Initially subject to much criticism, the novel has acquired a dominant position amongst literary forms, both popularly and critically.[59][62][63]

Novella

In purely quantitative terms, the novella exists between the novel and short story; the publisher Melville House classifies it as "too short to be a novel, too long to be a short story".[64] There is no precise definition in terms of word or page count.[65]Literary prizes and publishing houses often have their own arbitrary limits,[66] which vary according to their particular intentions. Summarizing the variable definitions of the novella, William Giraldi concludes "[it is a form] whose identity seems destined to be disputed into perpetuity".[67] It has been suggested that the size restriction of the form produces various stylistic results, both some that are shared with the novel or short story,[65][68][69] and others unique to the form.[70]

Short story

A dilemma in defining the "short story" as a literary form is how to, or whether one should, distinguish it from any short narrative; hence it also has a contested origin,[71] variably suggested as the earliest short narratives (e.g. the Bible), early short story writers (e.g. Edgar Allan Poe), or the clearly modern short story writers (e.g. Anton Chekhov).[72] Apart from its distinct size, various theorists have suggested that the short story has a characteristic subject matter or structure;[73][74] these discussions often position the form in some relation to the novel.[75]

Essays

An essay consists of a discussion of a topic from an author's personal point of view, exemplified by works by Michel de Montaigne or by Charles Lamb.[citation needed] Genres related to the essay may include the memoir and the epistle.

Natural science

As advances and specialization have made new scientific research inaccessible to most audiences, the "literary" nature of science writing has become less pronounced over the last two centuries. Now, science appears mostly in journals. Scientific works of Aristotle, Copernicus, and Newton still exhibit great value, but since the science in them has largely become outdated, they no longer serve for scientific instruction. Yet, they remain too technical to sit well in most programs of literary study. Outside of "history of science" programs, students rarely read such works.[citation needed]

Philosophy

Philosophy has become an increasingly academic discipline. More of its practitioners lament this situation than occurs with the sciences; nonetheless most new philosophical work appears in academic journals. Major philosophers through history—Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, Augustine, Descartes, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche—have become as canonical as any writers. Philosophical writing spans from humanistic prose to formal logic, the latter having become extremely technical to a degree similar to that of mathematics.[citation needed]

History

A significant portion of historical writing ranks as literature, particularly the genre known as creative nonfiction, as can a great deal of journalism, such as literary journalism. However, these areas have become extremely large, and often have a primarily utilitarian purpose: to record data or convey immediate information. As a result, the writing in these fields often lacks a literary quality, although it often(and in its better moments)has that quality. Major "literary" historians include Herodotus, Thucydides and Procopius, all of whom count as canonical literary figures.[citation needed]

Law

Law offers more ambiguity. Some writings of Plato and Aristotle, the law tables of Hammurabi of Babylon, or even the early parts of the Bible could be seen as legal literature. Roman civil law as codified in the Corpus Juris Civilis during the reign of Justinian I of the Byzantine Empire has a reputation as significant literature. The founding documents of many countries, including Constitutions and Law Codes, can count as literature.[citation needed]

Drama

Drama is literature intended for performance.[76] The form is often combined with music and dance, as in opera and musical theater. A play is a subset of this form, referring to the written dramatic work of a playwright that is intended for performance in a theater; it comprises chiefly dialogue between characters, and usually aims at dramatic or theatrical performance rather than at reading. A closet drama, by contrast, refers to a play written to be read rather than to be performed; hence, it is intended that the meaning of such a work can be realized fully on the page.[77] Nearly all drama took verse form until comparatively recently.

Greek drama exemplifies the earliest form of drama of which we have substantial knowledge. Tragedy, as a dramatic genre, developed as a performance associated with religious and civic festivals, typically enacting or developing upon well-known historical or mythological themes. Tragedies generally presented very serious themes. With the advent of newer technologies, scripts written for non-stage media have been added to this form. War of the Worlds (radio) in 1938 saw the advent of literature written for radio broadcast, and many works of Drama have been adapted for film or television. Conversely, television, film, and radio literature have been adapted to printed or electronic media.

Other narrative forms

Electronic literature is a literary genre consisting of works that originate in digital environments.

Films, videos and broadcast soap operas have carved out a niche which often parallels the functionality of prose fiction.

Graphic novels and comic books present stories told in a combination of sequential artwork, dialogue and text.

Literary techniques

Literary technique and literary device are used by authors to produce specific effects.

Literary techniques encompass a wide range of approaches: examples for fiction are, whether a work is narrated in first-person, or from another perspective; whether a traditional linear narrative or a nonlinear narrative is used; the literary genre that is chosen.

Literary devices involves specific elements within the work that make it effective. Examples include metaphor, simile, ellipsis, narrative motifs, and allegory. Even simple word play functions as a literary device. In fiction stream-of-consciousness narrative is a literary device.

Legal status

United Kingdom

Literary works have been protected by copyright law from unauthorized reproduction since at least 1710.[78] Literary works are defined by copyright law to mean any work, other than a dramatic or musical work, which is written, spoken or sung, and accordingly includes (a) a table or compilation (other than a database), (b) a computer program, (c) preparatory design material for a computer program, and (d) a database.

Literary works are not limited to works of literature, but include all works expressed in print or writing (other than dramatic or musical works).[79]

Awards

There are numerous awards recognizing achievement and contribution in literature. Given the diversity of the field, awards are typically limited in scope, usually on: form, genre, language, nationality and output (e.g. for first-time writers or debut novels).[80]

The Nobel Prize in Literature was one of the six Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895,[81] and is awarded to an author on the basis of their body of work, rather than to, or for, a particular work itself.[a] Other literary prizes for which all nationalities are eligible include: the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, the Man Booker International Prize and the Franz Kafka Prize.

See also

|

- Philosophy and literature

- Lists

- List of authors

- List of books

- List of literary magazines

- List of literary terms

- List of women writers

- List of writers

- Related topics

- Asemic writing

- Childhood in literature

- Children's literature

Cultural movement for literary movements.- English studies

- Ergodic literature

- Erotic literature

- Hinman collator

- Hungryalism

- Literature basic topics

- Literary agent

- Literature cycle

- Literary element

- Literary magazine

- Modern Language Association

- Orature

- Postcolonial literature

- Postmodern literature

- Popular fiction

- Rabbinic literature

- Rhetorical modes

- Vernacular literature

- World literature

Notes

^ However, in some instances a work has been cited in the explanation of why the award was given.

References

Citations

^ ab Leitch et al., The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 28

^ Ross, "The Emergence of "Literature": Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century", 406

^ Eagleton 2008, p. 16.

^ ab Eagleton 2008, p. 9.

^ Biswas, Critique of Poetics, 538

^ Leitch et al., The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 4

^ Eagleton 2008, p. 2-6.

^ ab Meyer, Jim (1997). "What is Literature? A Definition Based on Prototypes". Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session. 41 (1). Retrieved 11 February 2014..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Eagleton 2008, p. 4.

^ "literature (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

^ Finnegan, Ruth (1974). "How Oral Is Oral Literature?". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 37 (1): 52–64. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00094842. JSTOR 614104.

(subscription required)

^ Abrams, Meyer Howard (1999). Glossary of Literary Terms. New York: Harcourt Brace College Publishers. p. 108. ISBN 9780155054523.

^ Foster 2001, p. 19.

^ Black et al. The Literature of Ancient Sumer, xix

^ Foster 2001, p. 7.

^ Foster 2001, p. 8.

^ Foster 2001, p. 9.

^ Michalowski p. 146

^ Black p. 5

^ Black et al., Introduction

^ Michalowski p. 144

^ ab Krause, Dagmar (2005). Timothy Findley's Novels Between Ethics and Postmodernism. Wurzburg: Königshausen & Neumann. p. 21. ISBN 3826030052.

^ ab Weston, Michael (2001). Philosophy, Literature and the Human Good. London: Routledge. pp. xix, 133. ISBN 0415243378.

^ Schelling, F.W.J. (2007). Historical-critical Introduction to the Philosophy of Mythology. New York: SUNY Press. p. 49. ISBN 9780791471319.

^ Lord Byron, (2008) Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage: Canto I. Lord Byron: The Major Works. ed. McGann, J.J. New York: Oxford University Press

^ English: a degree for the curious. (2013, September 16). UWIRE Text, p. 1. Retrieved from:http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA342994126&v=2.1&u=otta77973&it=r&p=AONE&sw=w&asid=0b1f124b2250452bd1bab5551e352af3

^ A Hyatt Mayor, Prints and People, Metropolitan Museum of Art/Princeton, 1971, nos 1–4.

ISBN 0-691-00326-2

^ Gavin Flood sums up mainstream estimates, according to which the Rigveda was compiled from as early as 1500 BCE over a period of several centuries. Flood 1996, p. 37

^ Aristophanes: Butts K.J.Dover (ed), Oxford University Press 1970, Intro. p. x.

^ Hogan 2011, p. 1.

^ Mitchell, Diana (2001). "From the Secondary Section: Young Adult Literature and the English Teacher". The English Journal. 90 (3): 23–25. JSTOR 821301.

^ Oebel, Guido (2001). So-called "Alternative FLL-Approaches". Norderstedt: GRIN Verlag. ISBN 9783640187799.

^ Damon, William; Lerner, Richard; Renninger, Ann; Sigel, Irving (2006). Handbook of Child Psychology, Child Psychology in Practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. p. 90. ISBN 0471272876.

^ Makin, Michael; Kelly, Catriona; Shepher, David; de Rambures, Dominique (1989). Discontinuous Discourses in Modern Russian Literature. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 122. ISBN 9781349198511.

^ Cullingford, Cedric (1998). Children's Literature and its Effects. London: A&C Black. p. 5. ISBN 0304700924.

^ Hogan 2011, p. 10.

^ Hogan 2011, p. 11.

^ ab Nezami, S.R.A. (February 2012). "The use of figures of speech as a literary device—a specific mode of expression in English literature". Language in India. 12 (2): 659–.

^ Hogan 2011, p. 19.

^ Paris 1986, p. 61.

^ Paris 1986, p. 25.

^ Paris 1986, p. 65.

^ ab "poetry, n." Oxford English Dictionary. OUP. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

(subscription required)

^ ab Preminger 1993, p. 938.

^ ab Preminger 1993, p. 939.

^ "Poetic Form: Prose Poem". Poets.org. Academy of American Poets. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

^ Preminger 1993, p. 981.

^ Preminger 1993, p. 979.

^ Lipsky, Abram (1908). "Rhythm in Prose". The Sewanee Review. 16 (3): 277–289. JSTOR 27530906.

(subscription required)

^ Ross, "The Emergence of "Literature": Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century", 398

^ Finnegan, Ruth H. (1977). Oral poetry: its nature, significance, and social context. Indiana University Press. p. 66.

^ Magoun, Jr., Francis P. (1953). "Oral-Formulaic Character of Anglo-Saxon Narrative Poetry". Speculum. 28 (3): 446–467. doi:10.2307/2847021. JSTOR 2847021.

(subscription required)

^ Alison Booth; Kelly J. Mays. "Glossary: P". LitWeb, the Norton Introduction to Literature Studyspace. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

^ Eliot T.S. 'Poetry & Prose: The Chapbook. Poetry Bookshop: London, 1921.

^ Graff, Richard (2005). "Prose versus Poetry in Early Greek Theories of Style". Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric. 23 (4): 303–335. doi:10.1525/rh.2005.23.4.303. JSTOR 10.1525/rh.2005.23.4.303.

(subscription required)

^ Sommerville, C. J. (1996). The News Revolution in England: Cultural Dynamics of Daily Information. Oxford: OUP. p. 18.

^ "Essay on Romance", Prose Works volume vi, p. 129, quoted in "Introduction" to Walter Scott's Quentin Durward, ed. Susan Maning. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992, p. xxv. Romance should not be confused with Harlequin Romance.

^ Doody (1996), p. 15.

^ ab "The Novel". A Guide to the Study of Literature: A Companion Text for Core Studies 6, Landmarks of Literature. Brooklyn College. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

^ Goody 2006, p. 19.

^ Goody 2006, p. 20.

^ Goody 2006, p. 29.

^ Franco Moretti, ed. (2006). "The Novel in Search of Itself: A Historical Morphology". The Novel, Volume 2: Forms and Themes. Princeton: Princeton UP. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-691-04948-9.

^ Antrim, Taylor (2010). "In Praise of Short". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

^ ab Giraldi 2008, p. 796.

^ Ripatrazone, Nick (17 September 2013). "Taut, Not Trite: On the Novella". The Millions. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

^ Giraldi 2008, p. 793.

^ Giraldi 2008, p. 795.

^ Fetherling, George (2006). "Briefly, the case for the novella". Seven Oaks Magazine. Archived from the original on 12 September 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

^ Norton, Ingrid. "Of Form, E-Readers, and Thwarted Genius: End of a Year with Short Novels". Open Letters Monthly. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

^ Boyd, William. "A short history of the short story". Prospect Magazine. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

^ Colibaba, Ştefan (2010). "The Nature of the Short Story: Attempts at Definition" (PDF). Synergy. 6 (2): 220–230. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

^ Rohrberger, Mary; Dan E. Burns (1982). "Short Fiction and the Numinous Realm: Another Attempt at Definition". Modern Fiction Studies. XXVIII (6).

^ May, Charles (1995). The Short Story. The Reality of Artifice. New York: Twain.

^ Marie Louise Pratt (1994). Charles May, ed. The Short Story: The Long and the Short of It. Athens: Ohio UP.

^ Elam, Kier (1980). The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama. London and New York: Methuen. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-416-72060-0.

^ Cody, Gabrielle H. (2007). The Columbia Encyclopedia of Modern Drama (Volume 1 ed.). New York City: Columbia University Press. p. 271.

^ The Statute of Anne 1710 and the Literary Copyright Act 1842 used the term "book". However, since 1911 the statutes have referred to literary works.

^ University of London Press v. University Tutorial Press [1916]

^ John Stock; Kealey Rigden (15 October 2013). "Man Booker 2013: Top 25 literary prizes". The Telegraph. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

^ "Facts on the Nobel Prize in Literature". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

A.R. Biswas (2005). Critique of Poetics (vol. 2). Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-269-0377-1.

Jeremy Black; Graham Cunningham; Eleanor Robson, eds. (2006). The literature of ancient Sumer. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-929633-0.

Cain, William E.; Finke, Laurie A.; Johnson, Barbara E.; McGowan, John; Williams, Jeffrey J. (2001). Vincent B. Leitch, ed. The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-97429-4.

Eagleton, Terry (2008). Literary theory: an introduction: anniversary edition (Anniversary, 2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-7921-8.

Flood, Gavin (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0.

Hogan, P. Colm (2011). What Literature Teaches Us about Emotion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Foster, John Lawrence (2001), Ancient Egyptian Literature: An Anthology, Austin: University of Texas Press, p. xx, ISBN 978-0-292-72527-0

Giraldi, William (2008). "The Novella's Long Life" (PDF). The Southern Review: 793–801. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

Goody, Jack (2006). "From Oral to Written: An Anthropological Breakthrough in Storytelling". In Franco Moretti. The Novel, Volume 1: History, Geography, and Culture. Princeton: Princeton UP. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-691-04947-2.

Paris, B.J. (1986). Third Force Psychology and the Study of Literature. Cranbury: Associated University Press.

Preminger, Alex; et al. (1993). The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. US: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02123-2.

Ross, Trevor (1996). "The Emergence of "Literature": Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century."" (PDF). ELH. 63 (2): 397–422. doi:10.1353/elh.1996.0019. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

Further reading

Major forms

Bonheim, Helmut (1982). The Narrative Modes: Techniques of the Short Story. Cambridge: Brewer. An overview of several hundred short stories.

Gillespie, Gerald (January 1967). "Novella, nouvelle, novella, short novel? — A review of terms". Neophilologus. 51 (1): 117–127. doi:10.1007/BF01511303.

History

Wheeler, L. Kip. "Periods of Literary History" (PDF). Carson-Newman University. Retrieved 18 March 2014. Brief summary of major periods in literary history of the Western tradition.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Literature. |

Library resources about Literature |

|

Project Gutenberg Online Library

Abacci – Project Gutenberg texts matched with Amazon reviews

Internet Book List similar to IMDb but for books- Internet Archive Digital eBook Collection