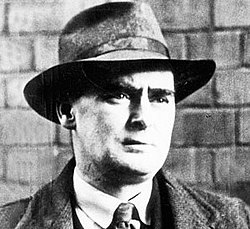

Brian O'Nolan

Brian O'Nolan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | (1911-10-05)5 October 1911 Strabane, County Tyrone, Ireland |

| Died | 1 April 1966(1966-04-01) (aged 54) Dublin, Ireland |

| Resting place | Deans Grange Cemetery, Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown |

| Pen name | Flann O'Brien Myles na gCopaleen Myles na Gopaleen Brother Barnabas George Knowall |

| Occupation | Civil servant, writer |

| Alma mater | University College, Dublin |

| Genre | Metafiction, satire |

| Notable works | At Swim-Two-Birds, The Third Policeman, An Béal Bocht, The Hard Life The Dalkey Archive "Cruiskeen Lawn" |

| Spouse | Evelyn McDonnell (1948–1966) |

Brian O'Nolan (Irish: Brian Ó Nualláin; 5 October 1911 – 1 April 1966) was an Irish novelist, playwright and satirist, considered a major figure in twentieth century Irish literature. Born in Strabane, County Tyrone, he is regarded as a key figure in postmodern literature.[1] His English language novels, such as At Swim-Two-Birds and The Third Policeman, were written under the pen name Flann O'Brien. His many satirical columns in The Irish Times and an Irish language novel An Béal Bocht were written under the name Myles na gCopaleen.

O'Nolan's novels have attracted a wide following for their bizarre humour and modernist metafiction. As a novelist, O'Nolan was influenced by James Joyce. He was nonetheless sceptical of the cult of Joyce which overshadows much of Irish writing, saying "I declare to God if I hear that name Joyce one more time I will surely froth at the gob."

Contents

1 Biography

1.1 School days

1.2 Student years

1.3 Civil service

1.4 Personal life

1.5 Health and death

2 Journalism

3 Etymology

4 Fiction

4.1 At Swim-Two-Birds

4.2 The Third Policeman and The Dalkey Archive

4.3 Other fiction

5 Legacy

6 List of works

7 Further reading

8 See also

9 References

10 External links

Biography

School days

O'Nolan attended Blackrock College where he was taught English by President of the College, and future Archbishop, John Charles McQuaid.[2]

According to Farragher and Wyer:

Dr McQuaid himself was recognised as an outstanding English teacher, and when one of his students, Brian O'Nolan, alias Myles na gCopaleen, boasted in his absence to the rest of the class that there were only two people in the College who could write English properly, namely, Dr McQuaid and himself, they had no hesitation in agreeing. And Dr McQuaid did Myles the honour of publishing a little verse by him in the first issue of the revived College Annual (1930) – this being Myles' first published item.[3]

The poem itself, "Ad Astra", read as follows:

Ah! When the skies at night

Are damascened with gold,

Methinks the endless sight

Eternity unrolled.[3]

O'Nolan also spent part of his schooling years in Synge Street Christian Brothers School. His novel The Hard Life is a semi autobiographical depiction of his experience of the Christian Brothers.

Student years

O'Nolan wrote prodigiously during his years as a student at University College, Dublin (UCD), where he was an active, and controversial, member of the well known Literary and Historical Society. He contributed to the student magazine Comhthrom Féinne (Fair Play) under various guises, in particular the pseudonym Brother Barnabas. Significantly, he composed a story during this same period titled "Scenes in a Novel (probably posthumous) by Brother Barnabas", which anticipates many of the ideas and themes later to be found in his novel, At Swim-Two-Birds. In it, the putative author of the story finds himself in riotous conflict with his characters, who are determined to follow their own paths regardless of the author's design. For example, the villain of the story, one Carruthers McDaid, intended by the author as the lowest form of scoundrel, "meant to sink slowly to absolutely the last extremities of human degradation", instead ekes out a modest living selling cats to elderly ladies and becomes a covert churchgoer without the author's consent. Meanwhile, the story's hero, Shaun Svoolish, chooses a comfortable, bourgeois life rather than romance and heroics:

- 'I may be a prig', he replied, 'but I know what I like. Why can't I marry Bridie and have a shot at the Civil Service?'

- 'Railway accidents are fortunately rare', I said finally, 'but when they happen they are horrible. Think it over.'

In 1934 O'Nolan and his student friends founded a short-lived magazine called Blather. The writing here, though clearly bearing the marks of youthful bravado, again somewhat anticipates O'Nolan's later work, in this case his Cruiskeen Lawn column as Myles na gCopaleen:

Blather is here. As we advance to make our bow, you will look in vain for signs of servility or of any evidence of a desire to please. We are an arrogant and depraved body of men. We are as proud as bantams and as vain as peacocks.

Blather doesn't care. A sardonic laugh escapes us as we bow, cruel and cynical hounds that we are. It is a terrible laugh, the laugh of lost men. Do you get the smell of porter?

O'Nolan, who had studied German in Dublin, may have spent at least parts of 1933 and 1934 in Germany, namely in Cologne and Bonn, although details are uncertain and contested. He claimed himself, in 1965, that he "spent many months in the Rhineland and at Bonn drifting away from the strict pursuit of study." So far, no external evidence has turned up that would back up this sojourn (or an also anecdotal short-term marriage to one 'Clara Ungerland' from Cologne). In their biography, Costello and van de Kamp, discussing the inconclusive evidence, state that "...it must remain a mystery, in the absence of documented evidence an area of mere speculation, representing in a way the other mysteries of the life of Brian O'Nolan that still defy the researcher."[4]

Civil service

A key feature of O'Nolan's personal situation was his status as an Irish government civil servant, who, as a result of his father's relatively early death, was obliged to support ten siblings, including an elder brother who was an unsuccessful writer. Given the desperate poverty of Ireland in the 1930s to 1960s, a job as a civil servant was considered prestigious, being both secure and pensionable with a reliable cash income in a largely agrarian economy. The Irish civil service has been, since the Irish Civil War, fairly strictly apolitical: Civil Service Regulations and the service's internal culture generally prohibit Civil Servants above the level of clerical officer from publicly expressing political views. As a practical matter, this meant that writing in newspapers on current events was, during O'Nolan's career, generally prohibited without departmental permission on an article-by-article, publication-by-publication basis. This fact alone contributed to O'Nolan's use of pseudonyms, though he had started to create character-authors even in his pre-civil service writings. O'Nolan rose to be quite senior, serving a private secretary to Seán T. O'Kelly (a minister and later President of Ireland) and Seán McEntee, a powerful political figure, both of whom almost certainly knew O'Nolan was na gCopaleen.[5]

In reality, that O'Nolan was Flann O'Brien and Myles na gCopaleen was an open secret, largely disregarded by his colleagues, who found his writing very entertaining; this was a function of the makeup of the civil service, which recruited leading graduates by competitive examination—it was an erudite and relatively liberal body in the Ireland of the 1930s to the 1970s. Nonetheless, had O'Nolan forced the issue, by using one of his known pseudonyms or his own name for an article that seriously upset politicians, consequences would likely have followed—hence the acute pseudonym problem in attributing his work today. He was, indeed, forced to retire from the civil service in 1953.[6] "A combination of his gradually deepening alcoholism and his habit of making derogatory remarks about senior politicians in his newspaper columns led to his forced retirement from the civil service in 1953.[7] (He departed, recalled a colleague, "in a final fanfare of f***s".[8])

Personal life

Although O'Nolan was a well known character in Dublin during his lifetime, relatively little is known about his personal life. He joined the Irish civil service in 1935, working in the Department of Local Government. From the time of his father's death in 1937, he supported his brothers and sisters, eleven in total, on his income.[9] On 2 December 1948 he married Evelyn McDonnell, a typist in the Department of Local Government. On his marriage he moved from his parental home in Blackrock to nearby Merrion Avenue, living at several further locations in South Dublin before his death.[10] The couple had no children.

Health and death

Grave of Brian O'Nolan/Brian Ó Nualláin, his parents and his wife, Deans Grange Cemetery, Dublin

O'Nolan was an alcoholic for much of his life and suffered from ill health in his later years.[11] He suffered from cancer of the throat and died from a heart attack on the morning of 1 April 1966.[9]

Journalism

As Myles na gCopaleen (or Myles na Gopaleen), O'Nolan wrote short columns for The Irish Times, mostly in English but also in Irish, which showed a manic imagination that still astonishes.

His newspaper column, "Cruiskeen Lawn" (transliterated from the Irish crúiscín lán, "full/brimming small-jug"), has its origins in a series of pseudonymous letters written to The Irish Times, originally intended to mock the publication in that same newspaper of a poem, "Spraying the Potatoes", by the writer Patrick Kavanagh:

| “ | I am no judge of poetry — the only poem I ever wrote was produced when I was body and soul in the gilded harness of Dame Laudanum — but I think Mr Kavanaugh [sic] is on the right track here. Perhaps the Irish Times, timeless champion of our peasantry, will oblige us with a series in this strain covering such rural complexities as inflamed goat-udders, warble-pocked shorthorn, contagious abortion, non-ovoid oviducts and nervous disorders among the gentlemen who pay the rent. | ” |

The letters, some written by O'Nolan and some not, continued under a variety of false names, using various styles and assaulting varied topics, including other letters by the same authors. The letters were a hit with the readers of The Irish Times, and R. M. Smyllie, then editor of the newspaper, shortly invited O'Nolan to contribute a column. Importantly, the Irish Times maintained that there were in fact three pseudonymous authors of the Cruiskeen Lawn column, which provided a certain amount of cover for O'Nolan as a civil servant when a column was particularly provocative.

The first column appeared on 4 October 1940, under the pseudonym "An Broc" ("The Badger"). In all subsequent columns the name "Myles na gCopaleen" ("Myles of the Little Horses" or "Myles of the Ponies" - a name taken from The Collegians, a novel by Gerald Griffin) was used. Initially, the column was composed in Irish, but soon English was used primarily, with occasional smatterings of German, French or Latin. The sometimes intensely satirical column's targets included the Dublin literary elite, Irish language revivalists, the Irish government, and the "Plain People of Ireland." The following column excerpt, in which the author wistfully recalls a brief sojourn in Germany as a student, illustrates the biting humor and scorn that informed the Cruiskeen Lawn writings:

| “ | I notice these days that the Green Isle is getting greener. Delightful ulcerations resembling buds pit the branches of our trees, clumpy daffodils can be seen on the upland lawn. Spring is coming and every decent girl is thinking of that new Spring costume. Time will run on smoother till Favonius re-inspire the frozen Meade and clothe in fresh attire the lily and rose that have not sown nor spun. Curse it, my mind races back to my Heidelberg days. Sonya and Lili. And Magda. And Ernst Schmutz, Georg Geier, Theodor Winkleman, Efrem Zimbalist, Otto Grün. And the accordion player Kurt Schachmann. And Doktor Oreille, descendant of Irish princes. Ich hab' mein Herz/ in Heidelberg verloren/ in einer lauen/ Sommernacht/ Ich war verliebt/ bis über beide/ Ohren/ und wie ein Röslein/hatt'/ Ihr Mund gelächt or something humpty tumpty tumpty tumpty tumpty mein Herz it schlägt am Neckarstrand. A very beautiful student melody. Beer and music and midnight swims in the Neckar. Chats in erse with Kun O'Meyer and John Marquess ... Alas, those chimes. Und als wir nahmen/ Abschied vor den Toren/ beim letzten Küss, da hab' Ich Klar erkannt/ dass Ich mein Herz/ in Heidelberg verloren/ MEIN HERZ/ es schlägt am Neck-ar-strand! Tumpty tumpty tum.

| ” |

Ó Nuallain/na gCopaleen wrote Cruiskeen Lawn for The Irish Times until the year of his death, 1966.

He contributed substantially to Envoy (he was "honorary editor" for the special number featuring James Joyce[12]) and formed part of the Envoy / McDaid's pub circle of artistic and literary figures that included Patrick Kavanagh, Anthony Cronin, Brendan Behan, John Jordan, Pearse Hutchinson, J.P. Donleavy and artist Desmond MacNamara who, at the author's request, created the book cover for the first edition of The Dalkey Archive. O'Nolan also contributed to The Bell. He also wrote a column titled Bones of Contention for the Nationalist and Leinster Times under the pseudonym George Knowall; those were collected in the volume Myles Away From Dublin.

Most of his later writings were occasional pieces published in periodicals, which explains why his work has only recently come to enjoy the considered attention of literary scholars. O'Nolan was notorious for his prolific use and creation of pseudonyms for much of his writing, including short stories, essays, and letters to editors, which has rendered the compilation of a complete bibliography of his writings an almost impossible task. He allegedly would write letters to the editor of The Irish Times complaining about his own articles published in that newspaper, for example in his regular Cruiskeen Lawn column, or irate, eccentric and even mildly deranged pseudonymous responses to his own pseudonymous letters, which gave rise to rampant speculation as to whether the author of a published letter existed or not. Not surprisingly, little of O'Nolan's pseudonymous activity has been verified.

Etymology

O'Nolan's journalistic pseudonym is taken from a character (Myles-na-Coppaleen) in Dion Boucicault's play The Colleen Bawn (itself an adaptation of Gerald Griffin's The Collegians), who is the stereotypical charming Irish rogue. At one point in the play, he sings the ancient anthem of the Irish Brigades on the Continent, the song "An Crúiscín Lán" (hence the name of the column in the Irish Times).

Capall is the Irish word for "horse" (from Vulgar Latin caballus), and 'een' (spelled ín in Irish) is a diminutive suffix. The prefix na gCapaillín is the genitive plural in his Ulster Irish dialect (the Standard Irish would be "Myles na gCapaillíní"), so Myles na gCopaleen means "Myles of the Little Horses". Capaillín is also the Irish word for "pony", as in the name of Ireland's most famous and ancient native horse breed, the Connemara pony.

O'Nolan himself always insisted on the translation "Myles of the Ponies", saying that he did not see why the principality of the pony should be subjugated to the imperialism of the horse.

Fiction

At Swim-Two-Birds

At Swim-Two-Birds works entirely with borrowed (and stolen) characters from other fiction and legend, on the grounds that there are already far too many existing fictional characters.

At Swim-Two-Birds is now recognised as one of the most significant modernist novels before 1945. Indeed it can be seen as a pioneer of postmodernism, although the academic Keith Hopper has argued that The Third Policeman, superficially less radical, is actually a more deeply subversive and proto-postmodernist work, and as such, possibly a representation of literary nonsense.

At Swim-Two-Birds was one of the last books that James Joyce read and he praised it to O'Nolan's friends—praise which was subsequently used for years as a blurb on reprints of O'Brien's novels. The book was also praised by Graham Greene, who was working as a reader when the book was put forward for publication and also the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, whose work might be said to bear some similarities to that of O'Brien.

The British writer Anthony Burgess stated, "If we don't cherish the work of Flann O'Brien we are stupid fools who don't deserve to have great men. Flann O'Brien is a very great man." Burgess included At Swim-Two-Birds on his list of Ninety-Nine Novels: The Best in English since 1939.

At Swim-Two-Birds has had a troubled publication history in the USA. Southern Illinois University Press has set up a Flann O'Brien Center and begun publishing all of O'Nolan's works. Consequently, academic attention to the novel has increased.

The Third Policeman and The Dalkey Archive

The rejection of The Third Policeman by publishers in his lifetime had a profound effect on O'Nolan. This is perhaps reflected in The Dalkey Archive, in which sections of The Third Policeman are recycled almost word for word, namely the atomic theory and the character De Selby.

The Third Policeman has a fantastic plot of a murderous protagonist let loose on a strange world peopled by fat policemen, played against a satire of academic debate on an eccentric philosopher called De Selby. Sergeant Pluck introduces the atomic theory of the bicycle.

The Dalkey Archive features a character who encounters a penitent, elderly and apparently unbalanced James Joyce (who dismissively refers to his work by saying 'I have published little' and, furthermore, does not seem aware of having written and published Finnegans Wake) working as an assistant barman or 'curate'—another small joke relating to Joyce's alleged priestly ambitions—in the resort of Skerries. The scientist De Selby seeks to suck all of the air out of the world, and Policeman Pluck learns of the mollycule theory from Sergeant Fottrell. The Dalkey Archive was adapted for the stage in September 1965 by Hugh Leonard as The Saints Go Cycling In.[13]

Other fiction

Other books written by O'Nolan include An Béal Bocht—translated from the Irish as The Poor Mouth—(a parody of Tomás Ó Criomhthain's autobiography An t-Oileánach—in English The Islander), and The Hard Life (a fictional autobiography meant to be his "misterpiece").

O'Nolan's theatrical output was unsuccessful. Faustus Kelly, a play about a local councillor selling his soul to the devil for a seat in the Dáil, ran for only 11 performances in 1943.[14] A second play, Rhapsody in Stephen's Green, also called The Insect Play, was a reworking of the Capek Brothers' synonymous play using anthropomorphised insects to satirise society. It also was put on in 1943 but quickly folded, possibly because of the offence it gave to various interests including Catholics, Ulster Protestants, Irish civil servants, Corkmen, and the Fianna Fail party.[15] The play was thought lost, but was rediscovered in 1994 in the archives of Northwestern University.[16]

In 1956, O'Nolan was co-producer of a production for RTÉ, the Irish broadcaster, of 3 Radio Ballets, which was just what it said it was—a dance performance in three parts designed for and performed on radio.

Legacy

Blue plaque for O'Nolan at Bowling Green, Strabane

O'Brien influenced the science fiction writer and conspiracy theory satirist Robert Anton Wilson, who has O'Brien's character De Selby, an obscure intellectual in The Third Policeman and The Dalkey Archive, appear in his own The Widow's Son. In both The Third Policeman and The Widow's Son, De Selby is the subject of long pseudo-scholarly footnotes. This is fitting, because O'Brien himself made free use of characters invented by other writers, claiming that there were too many fictional characters as is. O'Brien was also known for pulling the reader's leg by concocting elaborate conspiracy theories.

In 2011 the '100 Myles: The International Flann O'Brien Centenary Conference' (24–27 July) was held at The Department of English Studies at the University of Vienna, the success of which led to the establishment of 'The International Flann O'Brien Society'.[17] In October 2011, Trinity College Dublin hosted a weekend of events celebrating the centenary of his birth.[18] A commemorative 55c stamp featuring a portrait of O'Nolan's head as drawn by his brother Micheál Ó Nualláin[19] was issued for the same occasion.[20][21][22] This occurred some 52 years after the writer's famous criticism of the Irish postal service.[23] A bronze sculpture of the writer stands outside the Palace Bar on Dublin's Fleet Street.[24]Kevin Myers said, "Had Myles escaped he might have become a literary giant."[25]Fintan O'Toole said of O'Nolan "he could have been a celebrated national treasure – but he was far too radical for that."[6] An award winning radio play by Albrecht Behmel called Ist das Ihr Fahrrad, Mr. O'Brien? brought his life and work to the attention of a broader German audience in 2003.[26]

O'Nolan has also been semi-seriously referred to as a "scientific prophet" in relation to his writings on thermodynamics, quaternion theory and atomic theory.[27]

In 2012, on the 101st anniversary of his birth, O'Nolan was honoured with a commemorative Google Doodle.[28][29]

His life and works were celebrated on BBC Radio 4's Great Lives in December 2017.[30]

List of works

- As Myles na gCopaleen

An Béal Bocht / The Poor Mouth (Irish: 1941), (English: 1973)

Selections of Cruiskeen Lawn columns have been published in seven collections:

- The Best of Myles

- The Hair of the Dogma

- Further Cuttings from Cruiskeen Lawn

Flann O'Brien at War: Myles na gCopaleen 1940–1945 (also published as At War)- Myles Away from Dublin

- Myles Before Myles

- The Various Lives of Keats and Chapman

- As Flann O'Brien

At Swim-Two-Birds (1939)

The Hard Life (1962)

The Dalkey Archive (1964)

The Third Policeman (written 1939–40, published 1967)

Slattery's Sago Saga (unfinished)

A Bash in the Tunnel (Brighton: Clifton Books 1970), essays on James Joyce by Flann O'Brien, Patrick Kavanagh, Samuel Beckett, Ulick O'Connor & Edna O'Brien. John Ryan (editor).

Rhapsody in St Stephen's Green (adaptation of Pictures from the Insects' Life)[31]

Further reading

Brooker, Joseph (2004). Flann O'Brien. Tavistock: Northcote House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-74631-081-6..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

Clune, Anne; Hurson, Tess, eds. (1997). Conjuring Complexities: Essays on Flann O'Brien. Belfast: The Institute of Irish Studies. ISBN 0-85389-678-X.

Cronin, Anthony (2003). No Laughing Matter: The Life and Times of Flann O'Brien. Dublin: New Island Books. ISBN 1-904301-37-1.

Curran, Steven. "No, This is Not From The Bell: Brian O'Nolan's 1943 Cruiskeen Lawn Anthology". Éire-Ireland. Irish American Cultural Institute. 32 (2 & 3): 79–92. ISSN 1550-5162. (Summer/Fall 1997)

Curran, Steven. "Designs on an 'Elegant Utopia': Brian O'Nolan and Vocational Organisation". Bullán. Oxford: Willow Press. 2: 87–116. ISSN 1353-1913. (Winter/Spring 2001)

Curran, Steven. "Could Paddy Leave Off from Copying Just for Five Minutes?: Brian O'Nolan and Éire's Beveridge Plan". Irish University Review. International Association for the Study of Irish Literatures. 31 (2): 353–76. ISSN 0021-1427. (Autumn/Winter 2001)

Guinness, Jonathan (1997). Requiem for a Family Business. London, UK: Macmillan. pp. 8–9. ISBN 0-333-66191-5.

Hopper, Keith (1995). Flann O'Brien: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Postmodernist. Cork University Press. ISBN 1-85918-042-6.

Johnston, Denis (1977). "Myles na Gopaleen". In Ronsley, Joseph. Myth and Reality in Irish Literature. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0-88920-039-4.

Jordan, John (2006). "'Flann O'Brien'; 'A Letter to Myles'; and 'One of the Saddest Books Ever to Come Out of Ireland'". Crystal Clear: The Selected Prose of John Jordan. Dublin: Lilliput Press. ISBN 1-84351-066-9.

Long, Maebh (2014). Assembling Flann O'Brien. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-4411-8705-5.

Long, Maebh, ed. (2018). Yours Severely: The Collected Letters of Flann O'Brien. Champaign, Illinois: Dalkey Archive Press. ISBN 978-1-62897-183-5.

"An Interview with Desmond MacNamara". The Journal of Irish Literature. January 1981. ISSN 0047-2514.

McFadden, Hugh (Summer 2012). "Fantasy & Culture: Flann and Myles". Books Ireland. No. 340. Dublin. ISSN 0376-6039.

Murphy, Neil (Fall 2011). "Flann O'Brien's 'The Hard Life': The Gaze of the Medusa". Review of Contemporary Fiction: 148–161.

Murphy, Neil (Fall 2005). "Flann O'Brien". Review of Contemporary Fiction. XXV (3): 7–41.

Nolan, Val (Spring 2012). "Flann Fantasy and Science Fiction: O'Brien's Surprising Synthesis". Review of Contemporary Fiction. XXXI (2): 178–190.

O'Keeffe, Timothy, ed. (1973). Myles: Portraits of Brian O'Nolan. London, UK: Martin, Brian & O'Keeffe. ISBN 0856161500.

Riordan, Arthur (2005). Improbable Frequency. Nick Hern Books. ISBN 1-85459-875-9.

Vintaloro, Giordano (2009). L'A(rche)tipico Brian O'Nolan Comico e riso dalla tradizione al post- [The A(rche)typical Brian O'Nolan Comic and Laughter from Tradition to Post-] (PDF) (in Italian). Trieste: Battello Stampatore. ISBN 88-87208-50-6.

Wäppling, Eva (1984). Four Irish Legendary Figures in 'At Swim-Two-Birds': A Study of Flann O'Brien's Use of Finn, Suibhne, the Pooka and the Good Fairy. University of Uppsala. ISBN 91-554-1595-4.

See also

- Literary and Historical Society, University College Dublin

- Bloomsday

References

^ Kellogg, Carolyn (13 October 2011). "Celebrating Flann O'Brien". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

^ Farragher, Sean; Wyer, Annraoi (1995). Blackrock College 1860-1995. Dublin: Paraclete Press. ISBN 0946639191.

^ ab "Flann O'Brien's English Teacher: John Charles McQuaid". Séamus Sweeney Blog. 1 May 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

^ Costello, Peter; van de Kamp, Peter (1987). Flann O'Brien – An Illustrated Biography. London, UK: Bloomsbury. pp. 45–50. ISBN 0-7475-0129-7.

^ Curran, Steven (2001). "'Could Paddy Leave off from Copying Just for Five Minutes': Brian O'Nolan and Eire's Beveridge Plan". Irish University Review. 31 (2): 353–375.

^ ab O'Toole, Fintan (1 October 2011). "The Fantastic Flann O'Brien". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

^ McNally, Frank (14 May 2009). "An Irishman's Diary". The Irish Times. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

^ Phelan, Michael (1976). "A Watcher in the Wings: A Lingering Look at Myles na gCopaleen". Administration. Dublin: Institute of Public Administration of Ireland. 24 (2): 96–106. ISSN 0001-8325.

^ ab Ó Nualláin, Micheál (1 October 2011). "The Brother: memories of Brian". The Irish Times. Irish Times Trust. Retrieved 1 October 2011.In 1966 Brian was undergoing X-ray treatment for throat cancer. He was saved from the agony of dying from throat cancer by having a major heart attack. He died in that early morning of April 1st (April fool's day, his final joke).

^ "Flann O'Brien (1911-66)". Ricorso. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

^ Gale, Steven H., ed. (1996). "O'Nolan, Brian". Encyclopedia of British Humorists: Geoffrey Chaucer to John Cleese. Vol.2 (L-W). New York/London: Garland. p. 798. ISBN 978-0-8240-5990-3. Retrieved 13 October 2009 – via Google Books.

^ 'In 1951, whilst I was editor of the Irish literary periodical Envoy, I decided that it would be a fitting thing to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the death of James Joyce by bringing out a special number dedicated to him which would reflect the attitudes and opinions of his fellow countrymen towards their illustrious compatriot. To this end I began by inviting Brian Nolan to act as honorary editor for this particular issue. His own genius closely matched, without in any way resembling or attempting to counterfeit, Joyce's. But if the mantle of Joyce (or should we say the waistcoat?) were ever to be passed on, nobody would be half so deserving of it as the man whom under his other guises as Flan [sic] O'Brien and Myles Na gCopaleen, proved himself incontestably to be the most creative writer and mordant wit that Ireland had given us since Shem the Penman himself.' – John Ryan, Introduction to A Bash in the Tunnel (1970) John Ryan (1925–92) Ricorso

^ "The Saints Go Cycling In". Playography Ireland. Irish Theatre Institute. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

^ Coe, Jonathan (24 October 2013). "Clutching at Railings". London Review of Books. 35 (20): 21–22. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

^ "Rhapsody in Stephens Green & The Insect Play". The Lilliput Press. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

^ Lennon, Peter (17 November 1994). "From the dung heap of history". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

^ "The International Flann O'Brien Society". University of Vienna. 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

^ Nihill, Cian (15 October 2011). "Trinity celebrates Flann O'Brien centenary". The Irish Times.

^ "Seven Days". The Irish Times. 8 October 2011.

^ "Writer O'Nolan honoured by stamp". The Irish Times. 4 October 2011.

^ Sweeney, Ken (5 October 2011). "Stamp of approval on Flann O'Brien's centenary". The Belfast Telegraph.

^ McManus, Darragh (5 October 2011). "Flann O'Brien: lovable literary genius". The Guardian.

^ McNally, Frank (5 October 2011). "An Post gets the message, gives Myles a stamp". The Irish Times.In the course of the 1959 diatribe, he decried the low aesthetic standards of Irish philately and, calling for a better class of artist to be hired, suggested future stamps might also capture more realistic scenes from Irish life, such as "a Feena Fayl big shot fixing a job for a relative.

^ Nihill, Cian (6 October 2011). "Palace of inspiration: Sculptures of writers unveiled". The Irish Times.

^ Myers, Kevin (30 September 2011). "Had Myles escaped he might have become a literary giant". Irish Independent.

^ "Hörspiel des Monats/Jahres 2003". Akademie der Darstellenden Künste (in German). Retrieved 2 May 2012.

^ Keating, Sara (17 October 2011). "Trinity plays host to Flann 100 as admirers celebrate comic genius". The Irish Times.In a twist of Mylesian absurdity, however, the highlight of the day's cultural programme proved to be a science lecture by Prof Dermot Diamond, in which Diamond convincingly argued that O'Brien was not just a literary genius but a scientific prophet. Diamond set recent experiments in the fields of thermodynamics, quaternion theory and atomic theory against excerpts from O'Brien's books, suggesting that O'Brien anticipated some of the greatest scientific discoveries of the 20th century.

^ Doyle, Carmel (5 October 2012). "Google celebrates Irish author Brian O'Nolan in doodle today". Silicon Republic. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

^ "Who's that Irish person in today's Google Doodle?". The Daily Edge. 5 October 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2015.It would have been Irish writer Flann O'Brien's (aka Brian O'Nolan) 101st birthday today. Sound of Google to give him his own doodle for his birthday.

^ Presenter: Matthew Parris; Interviewed Guests: Will Gregory, Carol Taaffe; Producer: Toby Field (5 December 2017). "Great Lives: Series 44, Episode 1: Will Gregory on Flann O'Brien". Great Lives. BBC. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

^ O'Brien, Flann; Tracy, Robert (1994). Rhapsody in Stephen's Green: The Insect Play. Lilliput Press. ISBN 978-1-874675-27-3.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Brian O'Nolan |

Works by Brian O'Nolan at Open Library

Works by or about Brian O'Nolan in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

Brian O'Nolan Papers, 1914–1966 at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Special Collections Research Center

Flann O'Brien Papers at John J. Burns Library, Boston College