2000 Canadian federal election

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

301 seats in the House of Commons 151 seats needed for a majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 64.1%[1] ( | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

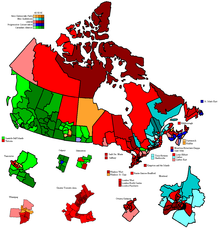

Popular vote by province, with graphs indicating the number of seats won. As this is an FPTP election, seat totals are not determined by popular vote by province but instead via results by each riding. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Map of Canada, showing the results of the 2000 election by riding.

The 2000 Canadian federal election was held on November 27, 2000, to elect 301 Members of Parliament of the House of Commons of Canada of the 37th Parliament of Canada.

Since the previous election of 1997, small-"c" conservatives had begun attempts to merge the Reform Party of Canada and Progressive Conservative Party of Canada as part of the United Alternative agenda. During that time, Jean Charest stepped down as leader of the Progressive Conservatives and former Prime Minister Joe Clark took over the party and opposed any union with the Reform Party. In spring of 2000, the Reform Party became the Canadian Alliance, a political party dedicated to uniting right-wing conservatives together into one party. Former Reform Party leader Preston Manning lost in a leadership race to Stockwell Day who became leader of the new Canadian Alliance party.

The federal government called an early election after being in office for just over three years (with a maximum allowed mandate of five years). The governing Liberal Party of Canada won a third consecutive majority government, winning more seats than the previous election. The Canadian Alliance made some minor gains, such as electing two Members of Parliament (MPs) from the province of Ontario. The Bloc Québécois, New Democratic Party (Canada) and the PC Party all lost seats. The 1993 and 1997 federal elections involved the issue of vote-splitting, between the Reform Party and the PC Party; this would repeated with the Alliance Party and the PC Party movements, which in Canada's First Past the Post system allowed many Liberal candidates with a plurality of votes to win.

This was the last election until 2011 which resulted in a majority government. It was the only election contested by the Canadian Alliance and the last by the Progressive Conservatives. This was also the first election in which Nunavut was its own separate territory (before, it was part of the Northwest Territories).

Contents

1 Campaign

2 Political parties

2.1 Liberal Party

2.1.1 Strategy

2.2 Canadian Alliance

2.3 Bloc Québécois

2.4 New Democratic Party

2.5 Progressive Conservative Party

3 Results

4 Vote and seat summaries

4.1 Results by province

4.2 Seat by seat results

5 Notes

5.1 10 closest ridings

6 See also

7 References

8 External links

Campaign

The decision by Prime Minister and Liberal Party leader Jean Chrétien to call an election in fall of 2000 has been viewed by commentators as an attempt to stem a possible rise of support to the newly formed Canadian Alliance, to stop the leadership ambitions of Paul Martin, and to capitalize on the nostalgia created by the recent death of Pierre Elliot Trudeau. At the time of the election, the Canadian economy was strong and there were few immediate negative issues, as the opposition parties were not prepared for the campaign.[3]

The major issue in the election was health care which had risen in public opinion polls to be the most important issue for Canadians.[4]

The public was largely uninterested in the election, with commentators stating that voters expected a repeat of previous regionally divided elections that offered little chance of a change of government.[5]

The Liberals' final television advertisement, according to Stephen Clarkson's The Big Red Machine: "emphasized the contrast between [the Liberals and the Canadian Alliance] while warning voters about [PC leader] Joe Clark's claim that he would form a coalition with the Bloc Québécois in a minority government. The ad told Canadians not to take risks with other parties but to choose a strong, proven team".[6]

Political parties

Liberal Party

Liberal Party logo during the election.

The Liberal Party entered the election with a record of having ended the fiscal deficit, made major reductions in federal spending (such as by cuts to the civil service, privatization of crown corporations), creating new environmental regulations, and increased spending beginning on social programs beginning in 1998 after the budget deficit had ended and a surplus had been achieved.[7] The Liberal Party came under attack by opposition parties for irregularities in the Department of Human Resources' Transition Job Fund program, but Chrétien managed to capably defend the government's actions.[7] Chrétien was directly attacked by the opposition parties for alleged corrupt involvement from the Prime Minister's Office (PMO) in providing funding to local projects in Chrétien's riding of Saint-Maurice.[8] The Liberal Party focused its attacks on the Canadian Alliance, accusing it of being a dangerous right-wing movement that was dangerous to national unity.[9] The Liberal Party's most tense problem was the ongoing leadership feud within the Liberal Party between Chrétien and Finance Minister Paul Martin who wanted to replace Chrétien as Liberal leader and Prime Minister.[10]

Strategy

Due to the regionalized nature of previous elections, the Liberal Party designed its election strategy along regional lines, aiming to take every seat in Ontario, winning seats in Quebec from the Bloc Québécois, and winning seats in Atlantic Canada, while attempting to minimize losses in Western Canada to the Canadian Alliance.[7]

Chrétien only spent parts of nine days campaigning in the West, including only two stops in the province of Alberta, both in the city of Edmonton while visiting the province of British Columbia only three times, and only in the cities of Victoria and Vancouver.[11]

The Liberal Party focused its effort in regaining support in Atlantic Canada, where the party had suffered serious losses in the 1997 election to the New Democratic Party and Progressive Conservative Party due to the Liberal government's imposition of quotas on Atlantic Canadian cod fisheries and the government's cuts to unemployment insurance benefits.[12] Chrétien gained support during the campaign from former New Brunswick Premier Frank McKenna and former Chrétien government minister and then the current Premier of Newfoundland and Labrador, Brian Tobin resigned as Premier and ran as a Liberal Party candidate in his province.[12] During the campaign, Chrétien apologized to Atlantic Canadians for the negative impact of employment insurance reforms which had caused hardship in Atlantic Canada.[12]

In Quebec, the Liberal Party benefited from the collapse of support for the Progressive Conservative Party, after the PCs' popular Québécois leader Jean Charest had resigned in 1998 and was replaced by former Prime Minister Joe Clark who was unpopular in Quebec which resulted in three PC members from Quebec defecting to join the Liberal Party prior to the election.[13] In Quebec the recently passed Clarity Act by the federal government was controversial in that it demanded a clear and concise question on a new referendum on sovereignty.[14] Chrétien defended the Clarity Act and attacked sovereigntist Quebec premier and former Bloc Québécois leader Lucien Bouchard, challenging him to hold another referendum on sovereignty under the new laws, as Chrétien expected that the sovereigntists would lose such a referendum.[14] The Liberal Party promised a number of government projects in Quebec to woo Quebec voters to the Liberal Party.[14]

The Liberal Party appealed to Canada's most populous province of Ontario by acting to restore funding that its government had cut in the 1990s in order to cut the deficit of the 1990s.[15] The Liberal government established a health accord with all premiers in September 2000 that involved major projected increases to public health care spending.[15] Overall, the Liberals increased their number of seats in the House of Commons from 155 seats to 172 seats.

Canadian Alliance

Canadian Alliance logo during the election.

The Canadian Alliance (the common short form name of Canadian Reform Conservative Alliance) was a new political party in the election, having been created only months earlier as the successor to the Reform Party of Canada, a party founded as a Western Canada protest party which sought to become a national party in the 1990s.[16] Reform Party leader Preston Manning was deeply disappointed with the Reform Party's failure to spread eastward in the 1997 election, as the Reform Party lost its only seat in Ontario in that election.[17] Reform identified vote-splitting with its rival conservative movement, the Progressive Conservative Party as the cause for the Liberals' 1997 election victory, and Manning proposed the solution of a merger of the Reform and Progressive Conservative parties.[18] This agenda by the Reform Party to unite the two parties was called the United Alternative which began in 1998, and ultimately resulted in the Alliance.[19]

The new party subsequently elected Stockwell Day as leader over Manning. The Alliance had hoped to use the 2000 election to eclipse the PC party in Ontario and Eastern Canada.[16] The Alliance dedicated its campaign to demonstrating that the party was a national party and not as western-based as its predecessor had been perceived as.[16] Day's more media friendly and "easy going" persona was expected to appeal to more Ontario voters than Manning's reputation as a policy wonk, and after the United Alternative project had integrated the successful Provincial PCs in the party, the Canadian Alliance was hoping for major improvements.

The Alliance campaigned on: cutting taxes by reducing the Federal taxation rate to two lower tax brackets, an end to the federal gun registration program, and importance of family values. The campaign was dogged by accusations: introducing a two-tier health care—the party would allow private health care to exist alongside the public medicare system; and for threatening the protection of gay rights and abortion rights. The latter accusations tended to focus on the party's residual[clarification needed]direct democracy provisions in their platform. The accusations against his party platform, along with Day's relative inexperience compared to decades-experienced fixtures like Clark and Chrétien, led to the party fading from contention.

While they did not force the Liberals into minority government or finally eclipse the PC party, they did retain their official opposition status, and increased their numbers in the House of Commons by six seats, from 60 to 66. The Alliance ended up winning only two Ontario ridings. On election night, controversy arose when a CBC producer's gratuitously sexist comment about Stockwell Day's daughter-in-law, Juliana Thiessen-Day, was accidentally broadcast on the Canadian networks' pooled election feed from Day's riding.

Bloc Québécois

Logo of the Bloc Québécois during the election.

The Bloc Québécois suffered from the unpopular decision of its provincial counterpart, the ruling Parti Québécois government's agenda to merge the communities surrounding Quebec City into one community.[20] Many Québécois were angered by this decision and voted in protest against the Bloc or chose to not vote at all to demonstrate their frustration.[21] Bloc leader Gilles Duceppe received negative media attention after he decided to personally appoint candidate Noël Tremblay to run in the riding of Chicoutimi—Le Fjord in spite of the Bloc's riding association's selection of Sylvain Gaudreault to run in the riding.[22] The Bloc's 177 page platform was criticized as being far too large and few copies were distributed and few internet users accessed the platform because of is length and was rarely discussed during the campaign.[23] Instead, the Bloc produced large numbers of copies of small booklets that outlined the policies within the large platform.[24] The Bloc campaigned to try to win over previous supporters of the PC Party.[24] This campaign strategy failed, as the Bloc lost seats to the Liberal Party due to the collapse of Quebec support for the Progressive Conservative Party, whose voters shifted to the Liberal Party.[25] The Bloc won in 38 ridings, six ridings fewer than in the 1997 election.

New Democratic Party

Logo of the New Democratic Party during the election.

The New Democratic Party suffered badly in the campaign due to the drop in support for the provincial New Democratic parties over the preceding decade and amid a scandal in 2000 facing British Columbia's NDP Premier Glen Clark who was forced to resign as Premier.[26] Matters were made worse for the federal NDP after Saskatchewan's NDP Premier Roy Romanow resigned in 2000 after the party lost seats in the 1999 Saskatchewan provincial election, and afterwards suggested that the federal NDP should merge with the Liberal Party.[26] In Nova Scotia, the provincial NDP lost seats in its 1999 election while the NDP government of the Yukon had been recently defeated.[26] As Canada's major social democratic political party, it relied on support from the labour movement, but recent strains between the NDP and the Canadian Auto Workers union and the Canadian Labour Congress had weakened the party's base of support.[26] The party had received little media attention during the election and 2000 as a whole, due to the media's focus on Canada's newest political party, the Canadian Alliance, the political comeback of former Prime Minister Joe Clark to the leadership of the Progressive Conservative Party, and the leadership feud within the Liberal Party between Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin.[10] The NDP did not expect to do well in the election and aimed to win thirty-two "must-win" seats.[10]

The NDP's platform and campaign focused on protecting medicare while attacking the Liberal Party for its tax cuts to wealthy Canadians and corporations.[4] The NDP's focus on attacking the Liberals failed to recognize the surging support for the Canadian Alliance in the province of Saskatchewan, which the NDP had hoped to gain seats in.[27] The NDP failed to galvanize support, as it remained low in support in polling results throughout most of the election campaign.[28] NDP leader Alexa McDonough performed badly in the French-language debate due to her not being fluent in French.[29] In the English-language debate, McDonough attacked Alliance leader Stockwell Day for favouring two-tier health care and attacked Liberal leader Jean Chrétien for giving out tax cuts to the wealthy rather than funding Canada's public health care system.[29]

Progressive Conservative Party

Logo of the Progressive Conservative Party during the election.

The Progressive Conservative Party aimed to regain its former place in Canadian politics under the leadership of former Prime Minister Joe Clark. The PC Party had a very disappointing election, falling from 20 to 12 seats, and being almost exclusively confined to the Maritime provinces and Newfoundland. It won the 12 seats needed for Official party status in the House of Commons, however. Failure to win 12 seats might have marginalized the party in the House of Commons, and likely led to a more rapid decline.

It should be noted that governing parties have the option of extending party status to caucuses of less than twelve members at their discretion. Had the Progressive Conservatives been just a few seats short of the requisite twelve and the NDP had stayed at least twelve seats, the Liberal government would likely have exercised this option as they had done for Social Credit in 1974.

37th Parliament

Results

| ↓ | ||||

172 | 66 | 38 | 13 | 12 |

Liberal | Canadian Alliance | BQ | NDP | PC |

| Party | Party leader | Candidates | Seats | Popular vote | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1997 | Dissol. | Elected | % Change | # | % | Change | ||||

Liberal | Jean Chrétien | 301 | 155 | 161 | 172 | +11.0% | 5,252,031 | 40.85% | +2.39pp | |

Alliance | Stockwell Day | 298 | 60 | 58 | 66 | +10.0% | 3,276,929 | 25.49% | +6.13pp1 | |

Bloc Québécois | Gilles Duceppe | 75 | 44 | 44 | 38 | -13.6% | 1,377,727 | 10.72% | +0.04pp | |

New Democratic | Alexa McDonough | 298 | 21 | 19 | 13 | -38.1% | 1,093,868 | 8.51% | -2.54pp | |

Progressive Conservative | Joe Clark | 291 | 20 | 15 | 12 | -40.0% | 1,566,998 | 12.19% | -6.65pp | |

Green | Joan Russow | 111 | - | - | - | - | 104,402 | 0.81% | +0.38pp | |

Marijuana | Marc-Boris St-Maurice | 73 | * | - | - | * | 66,258 | 0.52% | * | |

| | No affiliation | 57 | - | - | - | - | 37,591 | 0.29% | +0.28pp | |

Canadian Action | Paul T. Hellyer | 70 | - | - | - | - | 27,103 | 0.21% | +0.08pp | |

| | Independent | 29 | 1 | 4 | - | -100% | 17,445 | 0.14% | -0.32pp | |

Natural Law | Neil Paterson | 69 | - | - | - | - | 16,577 | 0.13% | -0.16pp | |

Marxist–Leninist | Sandra L. Smith | 84 | - | - | - | - | 12,068 | 0.09% | - | |

Communist | Miguel Figueroa | 52 | * | - | - | * | 8,776 | 0.09% | * | |

| | Vacant | - | | |||||||

Total | 1,808 | 301 | 301 | 301 | ±0.0% | 12,857,773 | 100% | - | ||

Sources: http://www.elections.ca History of Federal Ridings since 1867 | ||||||||||

Notes:

"% change" refers to change from previous election

* - Party did not nominate candidates in the previous election

1 - percentage change from Reform Party of Canada in previous election.

Vote and seat summaries

Results by province

| Party name | BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | NB | NS | PE | NL | NU | NT | YK | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| | Liberal | Seats: | 5 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 100 | 36 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 172 |

| | Popular vote: | 27.7 | 20.9 | 20.7 | 32.5 | 51.5 | 44.2 | 41.7 | 36.5 | 47.0 | 44.9 | 69.0 | 45.3 | 32.9 | 40.8 | |

| | Canadian Alliance | Seats: | 27 | 23 | 10 | 4 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | | - | - | 66 |

| | Vote: | 49.4 | 58.9 | 47.7 | 30.4 | 23.6 | 6.2 | 15.7 | 9.6 | 5.0 | 3.9 | | 17.6 | 27.0 | 25.5 | |

| | Bloc Québécois | Seats: | | | | | | 38 | | | | | | | | 38 |

| | Vote: | | | | | | 39.9 | | | | | | | | 10.7 | |

| | New Democratic | Seats: | 2 | - | 2 | 4 | 1 | - | 1 | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | 13 |

| | Vote: | 11.3 | 5.4 | 26.2 | 20.9 | 8.3 | 1.8 | 11.7 | 24.0 | 9.0 | 13.1 | 18.3 | 26.9 | 32.1 | 8.5 | |

| | Progressive Conservative | Seats: | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | 3 | 4 | - | 2 | - | - | - | 12 |

| | Vote: | 7.3 | 13.5 | 4.8 | 14.5 | 14.4 | 5.6 | 30.5 | 29.1 | 38.4 | 34.5 | 8.1 | 10.1 | 7.6 | 12.2 | |

| Total seats: | 34 | 26 | 14 | 14 | 103 | 75 | 10 | 11 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 301 | ||

Parties that won no seats: | ||||||||||||||||

Green | Vote: | 2.1 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.6 | | 0.1 | 0.3 | | 4.5 | | | 0.8 | |

Marijuana | Vote: | 0.7 | 0.2 | | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | | | | | | 0.5 | |

Canadian Action | Vote: | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | | | | | | | | | 0.2 | |

| | Natural Law | Vote: | 0.1 | | | | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | | 0.1 | 0.1 | | | | 0.1 |

Marxist–Leninist | Vote: | 0.1 | | | | 0.1 | 0.2 | | 0.1 | | | | | | 0.1 | |

Communist | Vote: | 0.1 | | | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | | | | | | | | 0.1 | |

| | Other | Vote: | 0.4 | 0.4 | | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.2 | | 0.2 | 0.1 | 4.4 | | | 0.4 | 0.4 |

Source: Elections Canada

Seat by seat results

- Canadian federal election, 2000 (candidates)

Notes

Number of parties: 11

First appearance: Marijuana Party of Canada

Reappearance after hiatus: Communist Party of Canada

Final appearance: Natural Law Party of Canada, Progressive Conservative Party of Canada

First-and-only appearance: Canadian Alliance

10 closest ridings

1.Champlain, QC: Marcel Gagnon (BQ) def. Julie Boulet (Lib) by 15 votes

2.Laval Centre, QC: Madeleine Dalphond-Guiral (BQ) def. Pierre Lafleur (Lib) by 42 votes

3.Leeds—Grenville, ON: Joe Jordan (Lib) def. Gord Brown (CA) by 55 votes

4.Saskatoon—Rosetown—Biggar, SK: Carol Skelton (CA) def. Dennis Gruending (NDP) by 68 votes

5.Yukon, YT: Larry Bagnell (Lib) def. Louise Hardy (NDP) by 70 votes

6.Tobique—Mactaquac, NB: Andy Savoy (Lib) def. Gilles Bernier (PC) by 150 votes

7.Regina—Lumsden—Lake Centre, SK: Larry Spencer (CA) def. John Solomon (NDP) by 161 votes

8.Regina—Qu'Appelle, SK: Lorne Nystrom (NDP) def. Don Leier (CA) by 164 votes

9.Palliser, SK: Dick Proctor (NDP) def. Don Findlay (CA) by 209 votes

10.Matapédia—Matane, QC: Jean-Yves Roy (BQ) def. Marc Bélanger (Lib) by 276 votes

11.Cardigan, PE: Lawrence MacAulay (Lib) def. Kevin MacAdam (PC) by 276 votes

See also

- List of Canadian federal general elections

- List of political parties in Canada

Articles on parties' candidates in this election:

|

|

|

References

^ Pomfret, R. "Voter Turnout at Federal Elections and Referendums". Elections Canada. Elections Canada. Retrieved 10 February 2012..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ "Parliament of Canada - Party Standings in the House of Commons". Parliament of Canada. Parliament of Canada. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

^ Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. The Canadian general election of 2000. Dundurn Press Ltd., 2001.

ISBN 1-55002-356-X,

ISBN 978-1-55002-356-5. Pp. 8.

^ ab Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 122.

^ Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 10.

^ Stinson, Scott (6 May 2011). "Scott Stinson: Redefining the Liberals not a quick process". National Post. Archived from the original on 2012-07-14. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

^ abc Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 16.

^ Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 23.

^ Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 22-23.

^ abc Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 115.

^ Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 19.

^ abc Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 20.

^ Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 21.

^ abc Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 22.

^ ab Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 24.

^ abc Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 59.

^ Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 60.

^ Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 61.

^ Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 61-62.

^ Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 140.

^ Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 140-141.

^ Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 141.

^ Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 144.

^ ab Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 145.

^ Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 140, 145.

^ abcd Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 114.

^ Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 124.

^ Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 127-128.

^ ab Dornan, Christopher; Pammett, Jon H. Pp. 128.

External links

- Elections Canada: 2000 election

- Predicting the 2000 Canadian Election