Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Poincaré | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of France | |

In office 18 February 1913 – 18 February 1920 | |

| Prime Minister | Aristide Briand Louis Barthou Gaston Doumergue Alexandre Ribot Paul Painlevé Georges Clemenceau Alexandre Millerand |

| Preceded by | Armand Fallières |

| Succeeded by | Paul Deschanel |

| Prime Minister of France | |

In office 23 July 1926 – 29 July 1929 | |

| President | Gaston Doumergue |

| Preceded by | Édouard Herriot |

| Succeeded by | Aristide Briand |

In office 15 January 1922 – 8 June 1924 | |

| President | Alexandre Millerand |

| Preceded by | Aristide Briand |

| Succeeded by | Frédéric François-Marsal |

In office 21 January 1912 – 21 January 1913 | |

| President | Armand Fallières |

| Preceded by | Joseph Caillaux |

| Succeeded by | Aristide Briand |

| Minister of Finance | |

In office 23 July 1926 – 11 November 1928 | |

| Preceded by | Anatole de Monzie |

| Succeeded by | Henry Chéron |

In office 14 March 1906 – 25 October 1906 | |

| Prime Minister | Ferdinand Sarrien |

| Preceded by | Pierre Merlou |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Caillaux |

In office 30 May 1894 – 26 January 1895 | |

| Prime Minister | Charles Dupuy |

| Preceded by | Auguste Burdeau |

| Succeeded by | Alexandre Ribot |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

In office 15 January 1922 – 8 June 1924 | |

| Preceded by | Aristide Briand |

| Succeeded by | Edmond Lefebvre du Prey |

In office 14 January 1912 – 21 January 1913 | |

| Preceded by | Justin de Selves |

| Succeeded by | Charles Jonnart |

| Minister of Education | |

In office 26 January 1895 – 1 November 1895 | |

| Prime Minister | Alexandre Ribot |

| Preceded by | Georges Leygues |

| Succeeded by | Émile Combes |

In office 4 April 1893 – 3 December 1893 | |

| Prime Minister | Charles Dupuy |

| Preceded by | Charles Dupuy |

| Succeeded by | Eugène Spuller |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (1860-08-20)20 August 1860 Bar-le-Duc, France |

| Died | 15 October 1934(1934-10-15) (aged 74) Paris, France |

| Political party | Democratic Republican Alliance |

| Spouse(s) | Henriette Benucci (m. 1904) |

| Alma mater | University of Nantes University of Paris |

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (French pronunciation: [ʁɛmɔ̃ pwɛ̃kaʁe]; 20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French statesman who served three times as 58th Prime Minister of France, and as President of France from 1913 to 1920. He was a conservative leader, primarily committed to political and social stability.[1]

Trained in law, Poincaré was elected as a Deputy in 1887 and served in the cabinets of Dupuy and Ribot. In 1902, he co-founded the Democratic Republican Alliance, the most important centre-right party under the Third Republic, becoming Prime Minister in 1912 and serving as President of the Republic for 1913-20. He attempted to wield influence from what was normally a figurehead role, being noted for his strongly anti-German attitudes, visiting Russia in 1912 and 1914 to repair Franco-Russian relations, which had become strained over the Bosnian Crisis of 1908 and the Agadir Crisis of 1911, and playing an important role in the July Crisis of 1914. From 1917, he exercised less influence as his political rival Georges Clemenceau had become Prime Minister. At the Paris Peace Conference, he favoured Allied occupation of the Rhineland.

In 1922 Poincaré returned to power as Prime Minister. In 1923 he ordered the Occupation of the Ruhr to enforce payment of German reparations. By this time Poincaré was seen, especially in the English-speaking world, as an aggressive figure (Poincaré-la-Guerre) who had helped to cause the war in 1914 and who now favoured punitive anti-German policies. His government was defeated by the Cartel des Gauches at the elections of 1924. He served a third term as Prime Minister in 1926-9.

Contents

1 Early years

2 Early political career

3 First premiership

4 Presidency

4.1 Pre-war

4.2 July Crisis

4.3 Later war

5 Second premiership

6 Third premiership

7 Resignation and Death

8 Family

9 Ministries

9.1 First ministry, 21 January 1912 – 21 January 1913

9.2 Second ministry, 15 January 1922 – 29 March 1924

9.3 Third ministry, 29 March – 9 June 1924

9.4 Fourth ministry, 23 July 1926 – 11 November 1928

9.5 Fifth ministry, 11 November 1928 – 29 July 1929

10 Gallery

11 See also

12 Notes

13 Further reading

13.1 Primary sources

14 External links

Early years

Born in Bar-le-Duc, Meuse, France, Raymond Poincaré was the son of Nanine Marie Ficatier, who was deeply religious [2] and Nicolas Antonin Hélène Poincaré, a distinguished civil servant and meteorologist. Raymond was also the cousin of Henri Poincaré, the famous mathematician. Educated at the University of Paris, Raymond was called to the Paris Bar, and was for some time law editor of the Voltaire. He became at the age of 20 the youngest lawyer in France.[3] and was appointed Secrétaire de la Conférence du Barreau de Paris. As a lawyer, he successfully defended Jules Verne in a libel suit presented against the famous author by the chemist, Eugène Turpin, inventor of the explosive melinite, who claimed that the "mad scientist" character in Verne's book Facing the Flag was based on him.[4] At the age of 26, Poincaré was elected to the Chamber of Deputies, making him the youngest deputy in the entire chamber.[3]

Early political career

Poincaré had served for over a year in the Department of Agriculture when in 1887 he was elected deputy for the Meuse département. He made a great reputation in the Chamber as an economist, and sat on the budget commissions of 1890–1891 and 1892. He was minister of education, fine arts and religion in the first cabinet (April – November 1893) of Charles Dupuy, and minister of finance in the second and third (May 1894 – January 1895).

In Alexandre Ribot's cabinet, Poincaré became minister of public instruction. Although he was excluded from the Radical cabinet which followed, the revised scheme of death duties proposed by the new ministry was based upon his proposals of the previous year. He became vice-president of the chamber in the autumn of 1895 and, in spite of the bitter hostility of the Radicals, retained his position in 1896 and 1897.

Along with other followers of "Opportunist" Léon Gambetta, Poincaré founded the Democratic Republican Alliance (ARD) in 1902, which became the most important centre-right party under the Third Republic.

In 1906, he returned to the ministry of finance in the short-lived Sarrien ministry. Poincaré had retained his practice at the Bar during his political career, and he published several volumes of essays on literary and political subjects.

"Poincarism" was a political movement over the period 1902–20. In 1902, the term was used by Georges Clemenceau to define a young generation of conservative politicians who had lost the idealism of the founders of the republic. After 1911, the term was used to mean "national renewal" when faced with the German threat. After the First World War, "Poincarism" refers to his support of business and financial interests.[1] Poincaré was noted for his lifelong feud with Georges Clemenceau. Clemenceau and Poincaré absolutely detested one another and engaged in one of the longest running feuds in French politics. The British historian, Anthony Adamthwaite, described Poincaré as having an "obsession with Clemenceau verging on paranoia" and as a "cold fish whose one passion was cats".[5]

First premiership

Poincaré became Prime Minister in January 1912, and began a policy meant to block Germany's ambitions for "world power status", and worked to restore ties with France's ally, Russia.[6] During the Bosnian Crisis of 1908-1909, the Franco-Russian alliance had been badly strained when France refused to support Russia after Austria-Hungary, supported by Germany, threatened war. During the Second Moroccan Crisis in 1911, Russia refused to support France when Germany threatened war. The lack of French interest in supporting Russia during the Bosnia crisis was the nadir of Franco-Russian relations with Tsar Nicholas II making no effort to hide his displeasure at the lack of support from what was supposed to be his number one ally.[7] At the time, Nicholas seriously considered abrogating the alliance, and was only stopped by the lack of an alternative.[8] Russia's refusal to support France during the Second Moroccan Crisis in 1911 reflected the enduring bitterness caused in St. Petersburg by France's refusal to support Russia during the Bosnia crisis which ended with humiliation. Poincaré believed a rift in the Franco-Russian alliance could only benefit Germany. Germany would be encouraged to think that it was possible to threaten war with France as the Russians might not honour the alliance.[9] In August 1912, Poincaré visited Russia to meet Tsar Nicholas in order to strengthen diplomatic ties.[10] Poincaré believed the rapprochement would deter Germany from risking a demarche to war, and thus avoid a repeat of the Second Moroccan crisis.[10] Tsarist Russia, despite its Francophilia, was generally disdainful of most of the leaders of the Third Republic, but Poincaré was an exception, regarded in St. Petersburg as a strong leader who meant what he said.[11] The Russian Foreign Minister, Sergey Sazonov, in a report to Nicholas wrote that, after meeting Poincaré: "Russia possesses a sure and faithful friend, endowed with a political spirit above the line and an inflexible will.".[12]

At the same time, Poincaré favoured hoped to pursue an expansionist policy at the expense of the Germany's unofficial ally, the Ottoman Empire.[6] For historical, economic and religious reasons, the French had traditionally been very interested in the Levant region of the Middle East. France had for centuries been the protector of the Maronite Christians, most recently in 1860, when France had threatened war following the massacres of the Maronites by local Muslims and Druze, while the Ottoman authorities did nothing. In the early years of the 20th century, there was an influential Levantine lobby within France to argue that it was France's mission to take over Ottoman Syria (roughly what is now modern Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, the West Bank and the Gaza strip). Poincaré was a leading member of the Comité de l'Orient, the main group that advocated French expansionism in the Middle East.[3] Poincaré's willingness to begin a rapprochement with Imperial Germany in order to allow France to pursue its ambitions in the Middle East was strengthened by the outcome of the First Balkan War, where Bulgaria - whose army had been trained by a French military mission - rapidly defeated the Sultan's army - whose forces had been trained by the German military.[6] Bulgaria's swift victory over the Ottomans was a great blow to German prestige, and correspondingly boosted French confidence, something that allowed Poincaré to approach Berlin from a position of strength.[6]

Poincaré believed that the best policy was one of "firmness" where France would assert its interests forcefully while not excluding the possibility of better foreign relations.[6] After defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, French elites concluded that France could never hope to defeat Germany on its own, and the only way to defeat the Germany would be with the help of another great power.[13] Besides its military superiority, Germany had demographic superiority with 70 million people compared with France's 40 million people (not including the colonies) together with economic superiority as the German economy was three times larger than France's. Poincaré therefore rejected Caillaux's proposal for a Franco-German alliance, arguing that Paris would be the junior partner, thus tantamount to ending France's status as a great power.[14] By contrast, the Treaty powers known as the Triple Entente being between two more or less equal powers, would preserve the current status quo ante bellum.[14] Poincaré's foreign policy was essentially defensive as he wished to maintain France as a great power in face of Germany's demands for Weltpolitik ("World politics") under which the Germany sought to become the world's dominant power.[14] Poincaré's entire foreign policy was based on the old Roman saying si vis pacem, para bellum ("if you want peace, prepare for war"). He wanted to strengthen both France and Russia to such a point that they presented such a decisive margin of superiority as to deter Germany from going to war with either power, but at same time his foreign policy was not relentlessly anti-German.[14] Although he rejected Caillaux's ideas, he was prepared to improve Franco-German relations on specific issues.[14] A fiscal conservative, Poincaré was deeply concerned about the financial effects of an ever more costly arms race. Being from Lorraine, whether he was a revancharde (revanchist) is disputed[15]. His family house was requisitioned for three years during the war.[16] His speeches warned of the "German menace" and believed Caillaux's policy of rapprochement with Berlin would create an impression of French weakness in Wilhelm II's mind, being a man who only respected the strong.[14] The Canadian historians, Holger Herwig and Richard Hamilton, described Poincaré as: "Typically for a man on the right side of the republican center, Poincaré was anti-clerical, but not anti-religious, nationalist, but not bellicose, a defender of property rights, free markets and small government. No ideologue, he was a practical politician willing to work with any true Frenchmen but adamant in defending France from the Socialist Left, the Catholic Right and, of course, Germany".[14]

Presidency

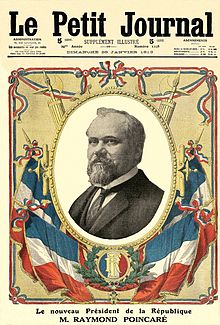

Le Petit Journal announces the election of Poincaré (1913).

Pre-war

Poincaré won election as President of the Republic in 1913, in succession to Armand Fallières. The strong-willed Poincaré was the first president of the Third Republic since MacMahon in the 1870s to attempt to make that office into a site of power rather than an empty ceremonial role. He asserted his personality and took a special interest in foreign policy.[3] On 20 January 1914, he became the first French president to visit the German embassy in Paris, a gesture clearly meant to show that he wanted to continue a policy of trying to improve German understanding of French aims.[6]

In early 1914, Poincaré found himself caught up in scandal when the leftish politician Joseph Caillaux threatened to publish letters showing that Poincaré was engaged in secret talks with the Vatican using the Italian government as an intermediary, which would have outraged anti-clerical opinion in France. Caillaux refrained from publishing the documents after the President pressured Gaston Calmette, editor of Le Figaro, not to publish documents showing that Caillaux had been unfaithful to his first wife, was involved in questionable financial dealings implicating a pro-German foreign policy. The matter might have remained settled had not the second Madame Caillaux, upset that Calmette might publish love letters written to her while her husband was still married to her predecessor, gone to Calmette's office on 16 March 1914 and shot him dead. The resulting scandal known as the Caillaux affair was the major French news story of the first half of 1914 causing Poincaré to joke that from now on he might send out Madame Poincaré to murder his political enemies since this method was working so well for Caillaux.[17]

July Crisis

On 28 June 1914, Poincaré was at the Longchamps racetrack when he received news of the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo.[18] The President remarked that the assassination was a tragedy, ordered an aide to draft a message of condolence to the people of Austria-Hungary and stayed on to enjoy the rest of the races.[18] The American historian, David Fromkin, has noted that the term "July Crisis" is actually a misnomer as it suggests that Europe was plunged into a crisis with the assassination of Franz Ferdinand on 28 June, but in fact the July crisis only began with the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum to Serbia, containing terms patently intended to inspire rejection, on 23 July 1914. The crisis was caused not by the assassination but rather by the decision in Vienna to use it as a pretext for a war with Serbia that many in the Austro-Hungarian government had long advocated.[19]

In 1913, it had been announced that Poincaré would visit St. Petersburg in July 1914 to meet Tsar Nicholas II. The Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister, Count Leopold von Berchtold, decided it was too dangerous for Austria-Hungary to present the ultimatum while the Franco-Russian summit was in progress and decided to wait until Poincaré was on board the battleship France that would take him home.[20] Accompanied by Premier René Viviani, Poincaré went to Russia for the second time (but for the first time as president) to reinforce the Franco-Russian Alliance. The transcripts of the St. Petersburg summit have been lost, but the surviving documentary evidence suggests that neither Nicholas nor Poincaré were particularly concerned about the situation in the Balkans.[21] At the time of the St. Petersburg summit, there were rumours, but little hard evidence, that Vienna might use the assassination to start a war with Serbia. When the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum was presented to Serbia on 23 July, the French government was in the hands of Jean-Baptiste Bienvenu-Martin, Minister of Justice and acting Premier. Bienvenu-Martin's inability to make decisions was especially exasperating to Philippe Berthelot, the most senior man in the Quai d'Orsay present in Paris, who complained that France was doing nothing while Europe was threatened with the prospect of war.[22] Furthermore, Poincaré's attempts to communicate with Paris were blocked by the Germans who jammed the radio messages between his ship and Paris.[21]

It was not until Poincaré had arrived back in Paris on 30 July 1914 that he finally learned of the crisis, and immediately attempted to stop matters from escalating into war.[23] With Poincaré's full approval, Viviani sent a telegram to Nicholas affirming that:

in the precautionary measures and defensive measures to which Russia believes herself obliged to resort, she should not immediately proceed to any measure which might offer Germany a pretext for a total or partial mobilization of her forces.[23]

Additionally, orders were given for French forces to pull back six miles from the frontier with Germany.[23]

The next day, 31 July, the German ambassador in Paris, Count Wilhelm von Schoen, presented to Viviani an ultimatum warning that, if Russian mobilisation continued, Germany would attack both France and Russia within the next 12 hours.[24] The ultimatum also demanded that France abrogate at once the alliance with Russia, allow German troops to march into France unopposed and turn over the fortresses in Verdun and Toul to the Germans to be occupied as long as Germany was at war with Russia.[25] In response, the French government ordered its ambassador in St. Petersburg, Maurice Paléologue, to find what was going on in Russia while refusing a request from General Joseph Joffre to order French mobilisation.[26]

However, the German ultimatum of 31 July 1914 left the French with two options: either to accept the humiliation of accepting the ultimatum, which would be the effective end of France as an independent nation, or go to war with Germany.[25] The American historian, Leonard Smith, together with the French historians, Annette Becker and Steéphane Audoin-Rouzeau, wrote that France had no option but to go to war as the prospect of accepting Schoen's ultimatum was too humiliating for the vast majority of the French people.[27] After Germany declared war on France following the rejection of the ultimatum, Poincaré appeared before the National Assembly to announce that France was now at war forming the doctrine of the union sacrée in which he announced that: "nothing will break the union sacrée in the face of the enemy."[28] « Dans la guerre qui s'engage, la France […] sera héroïquement défendue par tous ses fils, dont rien ne brisera devant l'ennemi l'union sacrée »

("In the coming war, France will be heroically defended by all its sons, whose sacred union will not break in the face of the enemy").

Later war

Poincaré became increasingly sidelined after the accession to power of Georges Clemenceau as Prime Minister in 1917. He believed the Armistice happened too soon and that the French Army should have penetrated far deeper into Germany.[29] At the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, negotiating the Treaty of Versailles, he wanted France to wrest the Rhineland from Germany to put it under Allied military control.[30] Poincaré wrote a memorandum for the conference, arguing that after the Franco-Prussian War, Germany occupied various French provinces and did not leave until it had received all of the indemnity exacted; whereas for the Great War, France wanted all reparations for damage caused. He further claimed that if the Allies did not occupy the Rhineland, they would at a later date find that they would need to do so again, and Germany would label them the aggressors:

And, further, shall we be sure of finding the left bank free from German troops? Germany is supposedly going to undertake to have neither troops nor fortresses on the left bank and within a zone extending 50 k.m. east of the Rhine. But the Treaty does not provide for any permanent supervision of troops and armaments on the left bank any more than elsewhere in Germany. In the absence of this permanent supervision, the clause stipulating that the League of Nations may order enquiries to be undertaken is in danger of being purely illusory. We can thus have no guarantee that after the expiry of the fifteen years and the evacuation of the left bank, the Germans will not filter troops by degrees into this district. Even supposing they have not previously done so, how can we prevent them doing it at the moment when we intend to re-occupy on account of their default? It will be simple for them to leap to the Rhine in a night and to seize this natural military frontier well ahead of us. The option to renew the occupation should not therefore from any point of view be substituted for occupation.[31]

Ferdinand Foch urged Poincaré to invoke his powers as laid down in the constitution and take over the negotiations of the treaty due to worries that Clemenceau was not achieving France's aims.[32] He did not, and when the French Cabinet approved of the terms which Clemenceau obtained, Poincaré considered resigning, although again he refrained.[33]

Second premiership

1923 caricature of Poincaré

In 1920, Poincaré's term as President came to an end, and two years later he returned to office as Prime Minister. Once again, his tenure was noted for its strong anti-German policies, with Poincaré justifying these by saying: "Germany's population was increasing, her industries were intact, she had no factories to reconstruct, she had no flooded mines. Her resources were intact, above and below ground... [i]n fifteen or twenty years Germany would be mistress of Europe. In front of her would be France with a population scarcely increased."[34]

Frustrated at Germany's unwillingness to pay reparations, Poincaré hoped for joint Anglo-French economic sanctions against it in 1922, while opposing military action. In April 1922, Poincare was greatly alarmed by the Treaty of Rapallo, the beginning of a German-Soviet challenge to the international order established by the Treaty of Versailles. He was disturbed that British Prime Minister David Lloyd George did not share the French viewpoint, instead almost welcoming Rapallo as a chance to bring Soviet Russia into the international system.[35] Poincaré came to believe by May 1922 that if Rapallo could not convince the British that Germany was out to undercut the Versailles system by whatever means necessary, then nothing would, in which case France would just have to act alone.[36] Further adding to Poincaré's fears was the worldwide propaganda campaign started in April 1922 blaming France for World War I as a means of disproving Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles, which would thereby undermine the French claim to reparations.[37]

Early in 1922 began what the British historian John Keiger called

a lavishly funded propaganda campaign by Germany, but also the Soviet Union bent on discrediting its tsarist predecessors, which had a considerable effect on "Anglo-Saxon" and neutral countries, contributing in the postwar era to the image of France, and Poincaré in particular as Germanophobe, bellicose, militaristic and intent on restoring French hegemony to the European continent.[38]

In the German-Soviet propaganda of the 1920s, the July Crisis of 1914 was portrayed as Poincaré-la-guerre (Poincaré's war), in which an insanely militaristic and revanchiste Poincaré put into action the plans he had allegedly negotiated with Emperor Nicholas II in 1912 for the dismemberment of Germany.[39] The French Communist newspaper L'Humanité ran a front-page cover-story accusing Poincaré and Nicholas II of being the two men who plunged the world into war in 1914.[40] The Poincaré-la-guerre propaganda proved to be very effective in the 1920s, and to a certain extent Poincaré's reputation has still not recovered.[39] Keiger has also argued that

France was an excellent scapegoat on to whom the blame could be shifted. Because in a war with Germany in 1870 she had lost the two provinces of Alsace-Lorraine, it was suggested that for virtually the next half-century she had prepared for a war of revanche against Germany to regain the lost territories. Because from 1912 France's new leader Raymond Poincaré, who was a Lorrainer into the bargain, was determined to apply resolute policies and to strengthen the links with France's allies, particularly with Russia, it was suggested that he had plotted a war of revanche against Germany.... Poincaré was charged with having encouraged Russia to begin the conflict. The idea of Poincaré-la-guerre gained currency. It was picked up and used to all ends. In France, it was put to political use from 1926 when Poincare's opponents wished to prevent a return to power. Eventually when the argument subsided, facts had been manipulated and evidence distorted, inevitably confusion resulted and some of the mud had stuck.[39]

Keiger further argued that Poincaré was "a victim of his own success. In peacetime he had prepared relentlessly for any eventuality and worked for national unity," so when the war started in 1914 "the crisis had been well managed. Critics could not forgive a Lorrainer this coincidence."[41] The German and Soviet governments were united by a common opposition to the international order created by Versailles, and therefore attacking Versailles as founded upon the alleged Kriegsschuldlüge ("war guilt lie") was an excellent way of creating doubts about the moral validity of the Versailles treaty among people around the world. The fact that Poincaré happened to be an extremely strong proponent of upholding Versailles, and a conservative anti-communist to boot, was an additional bonus from the German-Soviet viewpoint to attacking him as the alleged author of World War I. Finally during World War I, Vladimir Lenin had called for "revolutionary defeatism"; namely for the Bolsheviks to work for defeat of Russia as the best way of bringing about a Communist revolution. The thesis of Poincaré-la-guerre with its claim that Nicholas II was waging a war of aggression on behalf of France would justify Lenin's arguably treasonous acts during wartime in working with his country's enemies for the defeat of Mother Russia. As those of a Russian patriot trying to stop an unjust war; if one were to accept the counter-thesis of Germany as the aggressor in 1914, then Lenin's policy of working with the Germans for the defeat of Russia would have to be seen in a different light. Likewise, in Soviet history books Nicholas was always portrayed as "Bloody Nicholas", a man so monstrous that shooting him and his entire family down in cold-blood in 1918 was a justified act of retribution; the thesis of Poincaré-la-guerre was a point often used to demonstrate to the Soviet people just how awful "Bloody Nicholas" was.

Throughout the spring and summer of 1922, Poincaré grew increasingly annoyed that the British continued to spurn his offers of an alliance with Britain, a feeling further enhanced by the fact that the French had broken the British diplomatic codes and thus Poincaré could and did read the disparaging comments made about him by Lord Curzon.[36] British officials like Curzon took the view that with Germany defeated, the main danger to British interests was now France, and thus British foreign policy should tilt towards Germany to counterbalance French power.[42] The British strongly objected to Poincaré's plan to seize the Ruhr as a way of forcing reparations payments, arguing that this "would only impair German recovery, topple the German government, [and] lead to internal anarchy and Bolshevism, without achieving the financial goals of the French."[43]

Poincaré for his part, while demanding that France's right to collect reparations was non-negotiable, did not wish a break with Britain. He was also prepared to compromise on German reparations, albeit highly reluctantly, if the British were willing to offer security guarantees and a reduction in French war debts.[37] Despite Poincaré's best efforts to work out an Anglo-French plan for Germany to pay reparations, the British continued to insist that the French lower their reparations demands on Germany, asking in July 1922 that the French accept a voluntary two-year moratorium on collecting reparations from Germany while at the same time insisted that they would accept no reduction in French war debts, even if the French were to reduce reparation claims.[44] By the summer of 1922, a vicious circle had been created: the more Germany defaulted on reparations, the more the British pressed for reductions in reparations, which in turn led to further defaults by the Germans out of the hope that reparations might be cancelled altogether.[45] Poincaré was greatly offended by the British demand that the French cancel all reparations for two years, which he saw as rewarding Germany for its repeated defaults and feared that once the reparations were stopped, they would never start again.[45] On 10 August 1922 Lloyd George told his cabinet that Britain should not "give in to the tender mercies of M. Poincaré and the French militarists," for that would mean that Britain had "yielded up control of Europe not to France, but to M. Poincaré and his chauvinistic friends."[46] It was British policy to encourage Germany to default on reparations out of the hope that this might force the French to occupy the Ruhr in response.[46] In November 1922, the British member of the reparations commission, Sir John Bradbury, told the American Colonel James Logan that the British government wanted "to let M. Poincaré try out his policy in the face of their sulky disapproval in the hope that, when M. Poincaré had gone a little way in his independent policy, the French people, feeling consequently the weakening of the franc, increased taxation, etc., would rise in their wrath and oust M. Poincaré before too much harm had been done."[46] By December 1922 he was faced with British-American-German hostility and saw coal for French steel production and money for reconstructing the devastated industrial areas draining away. Poincaré was exasperated with British failure to act, and wrote to the French ambassador in London:

Judging others by themselves, the English, who are blinded by their loyalty, have always thought that the Germans did not abide by their pledges inscribed in the Versailles Treaty because they had not frankly agreed to them.... We, on the contrary, believe that if Germany, far from making the slightest effort to carry out the treaty of peace, has always tried to escape her obligations, it is because until now she has not been convinced of her defeat.... We are also certain that Germany, as a nation, resigns herself to keep her pledged word only under the impact of necessity.[47]

Poincaré decided to occupy the Ruhr on 11 January 1923, to extract the reparations himself. This, according to historian Sally Marks, "was profitable and caused neither the German hyperinflation, which began in 1922 and ballooned because of German responses to the Ruhr occupation, nor the franc's 1924 collapse, which arose from French financial practices and the evaporation of reparations."[48] The profits, after Ruhr-Rhineland occupation costs, were nearly 900 million gold marks.[49] During the Ruhr crisis, Poincaré received a message from Édouard Herriot, who had been in close contact with the Soviet Foreign Commissar Georgy Chicherin that the Soviet Union wished to establish diplomatic relations with France.[50] Poincaré, despite his anti-communism, was interested in the Soviet offer, as it offered a way of perhaps severing the Soviet Union from Germany, but insisted that the Soviets would have to honor all of the Russian debts they had repudiated in 1918, plus pay the interest on the debts that had been accumulated since 1918 and, offer compensation to French businesses for all of their assets that the Soviet regime had nationalised.[51] Poincaré's conditions proved to be unacceptable to the Soviets.[51] Poincaré lost the 1924 parliamentary election "more from the franc's collapse and the ensuing taxation than from diplomatic isolation."[52]

Hall argues that Poincaré was not a vindictive nationalist. Despite his disagreements with Britain, he desired to preserve the Anglo-French entente. When he ordered the French occupation of the Ruhr valley in 1923, his aims were moderate. He did not try to revive Rhenish separatism. His major goal was the winning of German compliance with the Versailles treaty. Though Poincaré's aims were moderate, his inflexible methods and authoritarian personality led to the failure of his diplomacy.[53]

Third premiership

A 1932 electoral leaflet supporting Raymond Poincaré's achievements

Financial crisis brought him back to power in 1926, and he once again became Prime Minister and Finance Minister until his retirement in 1929. As Prime Minister, he enacted a number of franc stabilization policies, retroactively known as the Poincaré Stabilization Law.[54][55] His popularity as Prime Minister rose considerably following his return to the gold standard, so much so that his party won the April 1928 general election.[56]

As early as 1915, Raymond Poincaré introduced a controversial denaturalization law which was applied to naturalized French citizens with "enemy origins" who had continued to maintain their original nationality. Through another law passed in 1927, the government could denaturalize any new citizen who committed acts contrary to French "national interest".

Resignation and Death

Due to his ill health, Poincaré resigned as Prime Minister in July 1929, refusing to serve another term as Prime Minister.[57] He died in Paris on October 15, 1934 at the age of 74.

Family

His brother, Lucien Poincaré (1862–1920), a physicist, became inspector-general of public instruction in 1902. He is the author of La Physique moderne (1906) and L'Électricité (1907).

Jules Henri Poincaré (1854–1912), an even more distinguished physicist and mathematician, was his first cousin.

Ministries

First ministry, 21 January 1912 – 21 January 1913

|

|

Changes

- 12 January 1913 – Albert Lebrun succeeds Millerand as Minister of War. René Besnard succeeds Lebrun as Minister of Colonies.

Second ministry, 15 January 1922 – 29 March 1924

|

|

Changes

- 5 October 1922 – Maurice Colrat succeeds Barthou as Minister of Justice.

Third ministry, 29 March – 9 June 1924

|

|

Fourth ministry, 23 July 1926 – 11 November 1928

|

|

Changes

- 1 June 1928 – Louis Loucheur succeeds Fallières as Minister of Labour, Hygiene, Welfare Work, and Social Security Provisions

- 14 September 1928 – Laurent Eynac enters the ministry as Minister of Air. Henry Chéron succeeds Bokanowski as Minister of Commerce and Industry, and also becomes Minister of Posts and Telegraphs.

Fifth ministry, 11 November 1928 – 29 July 1929

|

|

Gallery

Portrait of President Poincaré by Pierre Carrier-Belleuse (ca. 1913)

Photo of President Poincaré (1913)

President Poincaré with the President Woodrow Wilson (1918)

Prime Minister Poincaré with Painlevé and Briand (1925)

Poincaré in his 30s.

See also

- French entry into World War I

- Interwar France

Notes

^ ab J. F. V. Keiger, Raymond Poincaré (Cambridge University Press, 2002) p126

^ ↑ a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i et j Rémy Porte, « Raymond Poincaré, le président de la Grande Guerre », Nouvelle Revue d'Histoire, no 88 de janvier-février 2017, p. 44-46

^ abcd Fromkin, David Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?, New York: Alfred Knopf, 2004 page 80.

^ A letter which Verne later sent to his brother Paul seems to suggest that, though acquitted due to Poincaré's spirited defence, Verne did intend to defame Turpin.

^ Adamthwaite, Anthony Review of Raymond Poincaré by J. F. V. Keiger pages 491-492 from The English Historical Review, Volume 114, Issue 456, April 1999 page 491.

^ abcdef Fromkin, David Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?, New York: Alfred Knopf, 2004 page 81.

^ Tomaszewski, Fiona "Pomp, Circumstance, and Realpolitik: The Evolution of the Triple Entente of Russia, Great Britain, and France" pages 362-380 from Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, Volume 47, Issue # 3, 1999 pages 369-370.

^ Tomaszewski, Fiona "Pomp, Circumstance, and Realpolitik: The Evolution of the Triple Entente of Russia, Great Britain, and France" pages 362-380 from Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, Volume 47, Issue # 3, 1999 page 370.

^ Tomaszewski, Fiona "Pomp, Circumstance, and Realpolitik: The Evolution of the Triple Entente of Russia, Great Britain, and France" pages 362-380 from Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, Volume 47, Issue # 3, 1999 pages 372-373.

^ ab Tomaszewski, Fiona "Pomp, Circumstance, and Realpolitik: The Evolution of the Triple Entente of Russia, Great Britain, and France" pages 362-380 from Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, Volume 47, Issue # 3, 1999 pages 373-374.

^ Tomaszewski, Fiona "Pomp, Circumstance, and Realpolitik: The Evolution of the Triple Entente of Russia, Great Britain, and France" pages 362-380 from Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, Volume 47, Issue # 3, 1999 page 373.

^ Tomaszewski, Fiona "Pomp, Circumstance, and Realpolitik: The Evolution of the Triple Entente of Russia, Great Britain, and France" pages 362-380 from Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, Volume 47, Issue # 3, 1999 page 374.

^ Smith, Leonard; Audoin-Rouzeau, Steéphane, & Becker, Annette France and the Great War, 1914-1918, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003 page 11

^ abcdefg Herwig, Holger & Hamilton, Richard Decisions for War, 1914-1917, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004 page 114.

^ http://centenaire.org/fr/espace-scientifique/que-dire-de-poincare

^ ↑ a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i et j Rémy Porte, « Raymond Poincaré, le président de la Grande Guerre », Nouvelle Revue d'Histoire, no 88 de janvier-février 2017, p. 44-46

^ Fromkin, David Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?, New York: Alfred Knopf, 2004 pages 142-143.

^ ab Fromkin, David Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?, New York: Alfred Knopf, 2004, page 138.

^ Fromkin, David Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?, New York: Alfred Knopf, 2004 page 264.

^ Fromkin, David Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?, New York: Alfred Knopf, 2004 pages 168-169.

^ ab Fromkin, David Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?, New York: Alfred Knopf, 2004 page 194.

^ Fromkin, David Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?, New York: Alfred Knopf, 2004 page 190.

^ abc Fromkin, David Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?, New York: Alfred Knopf, 2004 page 233.

^ Fromkin, David Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?, New York: Alfred Knopf, 2004 page 235.

^ ab Smith, Leonard; Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane, & Becker, Annette France and the Great War, 1914–1918, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003 page 26.

^ Fromkin, David Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?, New York: Alfred Knopf, 2004 pages 235-236.

^ Smith, Leonard; Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane, & Becker, Annette France and the Great War, 1914-1918, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003 page 27.

^ Smith, Leonard; Audoin-Rouzeau, Steéphane, & Becker, Annette France and the Great War, 1914-1918, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003 page 27.

^ Margaret MacMillan, Peacemakers. The Paris Conference of 1919 and Its Attempt to End War (John Murray, 2003), p. 42.

^ MacMillan, p. 182.

^ Ernest R. Troughton, It's Happening Again (London: John Gifford, 1944), p. 21.

^ MacMillan, p. 212.

^ MacMillan, p. 214.

^ Étienne Mantoux, The Carthaginian Peace, or The Economic Consequences of Mr. Keynes (London: Oxford University Press, 1946), p. 23.

^ Keiger, John Raymond Poincaré, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002 p. 288.

^ ab Keiger, John Raymond Poincaré, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002 p. 290.

^ ab Keiger, John Raymond Poincaré, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002 p. 291.

^ Mombauer, Annika The Origins of the First World War, London: Pearson, 2002 p. 95.

^ abc Mombauer, Annika The Origins of the First World War, London: Pearson, 2002 p. 200.

^ Mombauer, Annika The Origins of the First World War, London: Pearson, 2002 p. 94.

^ Mombauer, Annika The Origins of the First World War, London: Pearson, 2002 p. 103.

^ Keiger, John Raymond Poincaré, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002 p. 287.

^ Ephraim Maisel (1994). The Foreign Office and Foreign Policy, 1919-1926. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 122–23..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Keiger, John Raymond Poincaré, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002 pp. 291–293.

^ ab Marks, Sally The Illusion of Peace, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003 p. 53

^ abc Keiger, John Raymond Poincaré, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002 p. 293.

^ Leopold Schwarzschild, World in Trance (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1943), p. 140.

^ Sally Marks, '1918 and After. The Postwar Era', in Gordon Martel (ed.), The Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered. Second Edition (London: Routledge, 1999), p. 26.

^ Marks, p. 35, n. 57.

^ Carley, Michael Jabara "Episodes from the Early Cold War: Franco-Soviet Relations, 1917-1927" 1275-1305 from Europe-Asia Studies, Volume 52, Issue #7, November 2000 pp. 1278-1279

^ ab Carley, Michael Jabara "Episodes from the Early Cold War: Franco-Soviet Relations, 1917-1927" 1275-1305 from Europe-Asia Studies, Volume 52, Issue #7, November 2000 p. 1279

^ Marks, p. 26.

^ Hines H. Hall, III, "Poincare and Interwar Foreign Policy: 'L'Oublie de la Diplomatie' in Anglo-French Relations, 1922-1924," Proceedings of the Western Society for French History (1982), Vol. 10, pp. 485–494.

^ Yee, Robert (2018). "The Bank of France and the Gold Dependency: Observations on the Bank's Weekly Balance Sheets and Reserves, 1898-1940" (PDF). Studies in Applied Economics. 128: 11.

^ Makinen, Gail; Woodward, G. Thomas (1989). "A Monetary Interpretation of the Poincaré Stabilization of 1926". Southern Economic Journal. 56 (1): 191.

^ "Raymond Poincaré". History.com.

^ "Raymond Poincaré". History.com.

Further reading

Philippe Bernard; Henri Dubief & Thony Forster (1985). The Decline of the Third Republic, 1914–1938. (Cambridge History of Modern France). Cambridge University Press.- Clark, Christopher. The sleepwalkers: How Europe went to war in 1914 (2012).

- Herwig, Holger & Richard Hamilton. Decisions for War, 1914-1917 (2004)

Keiger, J. F. V. (1997). Raymond Poincaré. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57387-4., review

Adamthwaite, Anthony (April 1999). "Review of Raymond Poincaré by J. F. V. Keiger". The English Historical Review. 114 (456): 491–492.

- Marks, Sally '1918 and After. The Postwar Era', in Gordon Martel (ed.), The Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 1999)

Jean-Marie Mayeur; Madeleine Rebirioux & J. R. Foster (1988). The Third Republic from its Origins to the Great War, 1871–1914. (Cambridge History of Modern France). Cambridge University Press.

Maisel, Ephraim (1994). The Foreign Office and Foreign Policy, 1919-1926. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 122–23.

Gordon Wright (1967). Raymond Poincaré and the French presidency. New York: Octagon Books. OCLC 405223.- Sisley Huddleston (1924). Poincaré: A Biographical Portrait, Little, Brown & Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Poincaré, Raymond". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Poincaré, Raymond". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Smith, Leonard; Audoin-Rouzeau, Steéphane; Becker, Annette (2003). France and the Great War, 1914-1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Primary sources

- Poincaré, Raymond. The origins of the war (1922) online free

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Raymond Poincare. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Raymond Poincaré |

Works by or about Raymond Poincaré at Internet Archive

Newspaper clippings about Raymond Poincaré in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Charles Dupuy | Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts 1893 | Succeeded by Eugène Spuller |

Minister of Worship 1893 | ||

| Preceded by Auguste Burdeau | Minister of Finance 1894–1895 | Succeeded by Alexandre Ribot |

| Preceded by Georges Leygues | Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts 1895 | Succeeded by Émile Combes |

| Preceded by Charles Dupuy | Minister of Worship 1895 | |

| Preceded by Pierre Merlou | Minister of Finance 1906 | Succeeded by Joseph Caillaux |

| Preceded by Joseph Caillaux | Prime Minister of France 1912–1913 | Succeeded by Aristide Briand |

| Preceded by Justin de Selves | Minister of Foreign Affairs 1912–1913 | Succeeded by Charles Jonnart |

| Preceded by Armand Fallières | President of France 1913–1920 | Succeeded by Paul Deschanel |

| Preceded by Aristide Briand | Prime Minister of France 1922–1924 | Succeeded by Frédéric François-Marsal |

Minister of Foreign Affairs 1922–1924 | Succeeded by Edmond Lefebvre du Prey | |

| Preceded by Édouard Herriot | Prime Minister of France 1926–1929 | Succeeded by Aristide Briand |

| Preceded by Anatole de Monzie | Minister of Finance 1926–1928 | Succeeded by Henry de Chéron |

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by Augustine Birrell | Rector of the University of Glasgow 1914–1919 | Succeeded by Bonar Law |

| Awards and achievements | ||

| Preceded by Eugene O'Neill | Cover of Time magazine 24 March 1924 | Succeeded by George Eastman |