David Ben-Gurion

| David Ben-Gurion דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st Prime Minister of Israel | |

In office 3 November 1955 – 26 June 1963 | |

| President | Yitzhak Ben-Zvi Zalman Shazar |

| Preceded by | Moshe Sharett |

| Succeeded by | Levi Eshkol |

In office 17 May 1948 – 26 January 1954 | |

| President | Chaim Weizmann Yitzhak Ben-Zvi |

| Deputy | Eliezer Kaplan |

| Preceded by | New office |

| Succeeded by | Moshe Sharett |

| Chairman of the Provisional State Council of Israel | |

In office 14 May 1948 – 16 May 1948 | |

| Preceded by | New office |

| Succeeded by | Chaim Weizmann |

| Minister of Defense | |

In office 21 February 1955 – 26 June 1963 | |

| Prime Minister | Moshe Sharett Himself |

| Preceded by | Pinhas Lavon |

| Succeeded by | Levi Eshkol |

In office 14 May 1948 – 26 January 1954 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | New office |

| Succeeded by | Pinhas Lavon |

| Personal details | |

| Born | David Grün (1886-10-16)16 October 1886 Płońsk, Congress Poland, Russian Empire |

| Died | 1 December 1973(1973-12-01) (aged 87) Ramat Gan, Israel |

| Nationality | |

| Political party | Mapai, Rafi, National List |

| Spouse(s) | Paula Ben-Gurion |

| Children | 3 |

| Alma mater | University of Warsaw Istanbul University |

| Signature | |

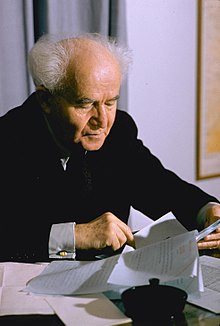

David Ben-Gurion (Hebrew: דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן; pronounced [daˈvɪd ben gurˈjo:n] (![]() listen), born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first Prime Minister of Israel.

listen), born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first Prime Minister of Israel.

Ben-Gurion's passion for Zionism, which began early in life, led him to become a major Zionist leader and Executive Head of the World Zionist Organization in 1946.[1] As head of the Jewish Agency from 1935, and later president of the Jewish Agency Executive, he was the de facto leader of the Jewish community in Palestine, and largely led its struggle for an independent Jewish state in Mandatory Palestine. On 14 May 1948, he formally proclaimed the establishment of the State of Israel, and was the first to sign the Israeli Declaration of Independence, which he had helped to write. Ben-Gurion led Israel during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and united the various Jewish militias into the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). Subsequently, he became known as "Israel's founding father".[2]

Following the war, Ben-Gurion served as Israel's first Prime Minister and Minister of Defense. As Prime Minister, he helped build the state institutions, presiding over various national projects aimed at the development of the country. He also oversaw the absorption of vast numbers of Jews from all over the world. A centerpiece of his foreign policy was improving relationships with the West Germans. He worked very well with Konrad Adenauer's government in Bonn, and West Germany provided large sums (in the Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany) in compensation for Nazi Germany's confiscation of Jewish property during the Holocaust.[3]

In 1954 he resigned as both Prime Minister and Minister of Defense, although he remained a member of the Knesset. However, he returned as Minister of Defense in 1955 after the Lavon Affair resulted in the resignation of Pinhas Lavon. Later in the year he became Prime Minister again, following the 1955 elections. Under his leadership, Israel responded aggressively to Arab guerrilla attacks, and in 1956, invaded Egypt along with British and French forces after Egypt nationalized the Suez Canal during what became known as the Suez Crisis.

He stepped down from office in 1963, and retired from political life in 1970. He then moved to Sde Boker, a kibbutz in the Negev desert, where he lived until his death. Posthumously, Ben-Gurion was named one of Time magazine's 100 Most Important People of the 20th century.

Contents

1 Life until 1918

1.1 Russian Empire

1.2 Ottoman Palestine and Constantinople

1.3 World War I

1.4 Family

2 Zionist leadership between 1919–1946

3 Views and opinions

3.1 Decisiveness and pragmatism

3.2 Attitude towards Arabs

3.3 Attitude towards the British

3.4 Attitude towards conquering West Bank

3.5 Religious parties and status quo

4 Military leadership

5 Founding of Israel

6 Later political career

7 Final years and death

8 Awards

9 Commemoration

10 See also

11 References

12 Further reading

13 External links

Life until 1918

David Ben-Gurion Square—site of the no longer existing house where Ben-Gurion was born, Płońsk, Wspólna Street.

House at town square in Płońsk, Poland, where David Ben-Gurion grew up

David and Paula Ben-Gurion, 1 June 1918.

Russian Empire

David Ben-Gurion was born in Płońsk in Congress Poland – then part of the Russian Empire. His father, Avigdor Grün, was a lawyer and a leader in the Hovevei Zion movement. His mother, Scheindel (Broitman),[4] died when he was 11 years old. Ben-Gurion's birth certificate, when rediscovered in Poland in 2003, indicated that he had a twin brother who died shortly after birth.[5] At the age of 14 he and two friends formed a youth club, Ezra, promoting Hebrew studies and emigration to the Holy Land.

From left: David Ben-Gurion and Paula with youngest daughter Renana on BG's lap, daughter Geula, father Avigdor Grün and son Amos, 1929

In 1905, as a student at the University of Warsaw, he joined the Social-Democratic Jewish Workers' Party – Poalei Zion. He was arrested twice during the Russian Revolution of 1905.

Ben-Gurion discussed his hometown in his memoirs, saying:

"For many of us, anti-Semitic feeling had little to do with our dedication [to Zionism]. I personally never suffered anti-Semitic persecution. Płońsk was remarkably free of it ... Nevertheless, and I think this very significant, it was Płońsk that sent the highest proportion of Jews to Eretz Israel from any town in Poland of comparable size. We emigrated not for negative reasons of escape but for the positive purpose of rebuilding a homeland ... Life in Płońsk was peaceful enough. There were three main communities: Russians, Jews and Poles. ... The number of Jews and Poles in the city were roughly equal, about five thousand each. The Jews, however, formed a compact, centralized group occupying the innermost districts whilst the Poles were more scattered, living in outlying areas and shading off into the peasantry. Consequently, when a gang of Jewish boys met a Polish gang the latter would almost inevitably represent a single suburb and thus be poorer in fighting potential than the Jews who even if their numbers were initially fewer could quickly call on reinforcements from the entire quarter. Far from being afraid of them, they were rather afraid of us. In general, however, relations were amicable, though distant."[6]

Ottoman Palestine and Constantinople

In 1906 he immigrated to Ottoman Palestine. A month after his arrival, he was elected to the central committee of the newly formed branch of Poalei Zion in Jaffa, becoming chairman of the party's platform committee. He advocated a more nationalist program than other more leftist or Marxist committee members. The following year he complained about the Russian domination of the group. At the time the Jewish population in Palestine was around 55,000 – of whom 40,000 held Russian citizenship.[citation needed]

Ben-Gurion worked picking oranges in Petah Tikva, and in 1907 he moved to the kibbutzim in Galilee, where he worked as an agricultural laborer and withdrew from politics. The following year, he joined an armed group acting as a watchmen. On 12 April 1909, following an attempted robbery in which an Arab from Kafr Kanna was killed, Ben-Gurion was involved in fighting during which one guard and a farmer from Sejera were killed.[7]

On 7 November 1911, Ben-Gurion arrived in Thessaloniki in order to learn Turkish for his law studies. The city, which had a large Jewish community, impressed Ben-Gurion, who called it "a Jewish city that has no equal in the world". He also realized there that "the Jews were capable of all types of work" Some of the city's Jews were rich businessmen and professors, while others were merchants, craftsmen and porters.[8]

In 1912, he moved to Constantinople, the Ottoman capital, to study law at Istanbul University together with Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, and adopted the Hebrew name Ben-Gurion, after the Jewish leading figure Yosef ben Gurion from the Great Jewish Revolt against the Romans. He also worked as a journalist. Ben-Gurion saw the future as dependent on the Ottoman regime.

World War I

Ben-Gurion was living in Jerusalem at the start of the First World War, where he and Ben Zvi recruited forty Jews into a Jewish militia to assist the Ottoman Army. Despite this he was deported to Egypt in March 1915. From there he made his way to the United States where he remained for three years. On his arrival he and Ben Zvi went on a tour of 35 cities in an attempt to raise a pioneer army, Hechalutz, of 10,000 men to fight on Turkey's side.[9]

Settling in New York City in 1915, he met Russian-born Paula Munweis. They were married in 1917.

After the Balfour Declaration of November 1917, the situation changed dramatically and in 1918 Ben-Gurion, with the interest of Zionism in mind, switched sides and joined the newly formed Jewish Legion of the British Army. He volunteered for the 38th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, one of the four which constituted the Jewish Legion. His unit fought against the Turks as part of Chaytor's Force during the Palestine Campaign.

Ben-Gurion and his family returned permanently to Palestine after World War I following its conquest by the British from the Ottoman Empire.

Ben-Gurion in his Jewish Legion uniform, 1918

Family

David and Paula Ben-Gurion had three children: a son, Amos, and two daughters, Geula Ben-Eliezer and Renana Leshem. Amos Ben-Gurion would become Deputy Inspector-General of the Israel Police, and also the director-general of a textile factory. He married Mary Callow, a gentile who converted to Judaism;[10][11]Joachim Prinz, a German rabbi who claimed to have converted her to Judaism, stated in 1946 that Mary was from the Isle of Man.[10] Amos and Mary Ben-Gurion had two daughters and a son, and six granddaughters. Geula had two sons and a daughter, and Renana, who worked as a microbiologist at the Israel Institute for Biological Research, had a son.[12]

Zionist leadership between 1919–1946

After the death of theorist Ber Borochov, the left-wing and centrist of Poalei Zion split in February 1919 with Ben-Gurion and his friend Berl Katznelson leading the centrist faction of the Labor Zionist movement. The moderate Poalei Zion formed Ahdut HaAvoda with Ben-Gurion as leader in March 1919. In 1920 he assisted in the formation of the Histadrut, the Zionist Labor Federation in Palestine, and served as its General Secretary from 1921 until 1935. At Ahdut HaAvoda's 3rd Congress, held in 1924 at Ein Harod, Shlomo Kaplansky, a veteran leader from Poalei Zion, proposed that the party should support the British Mandatory authorities' plans for setting up an elected legislative council in Palestine. He argued that a Parliament, even with an Arab majority, was the way forward. Ben-Gurion, already emerging as the leader of the Yishuv, succeeded in getting Kaplansky's ideas rejected.[13]

In 1930, Hapoel Hatzair (founded by A. D. Gordon in 1905) and Ahdut HaAvoda joined forces to create Mapai, the more moderate Zionist labor party (it was still a left-wing organization, but not as far-left as other factions) under Ben-Gurion's leadership. In the 1940s the left-wing of Mapai broke away to form Mapam. Labor Zionism became the dominant tendency in the World Zionist Organization and in 1935 Ben-Gurion became chairman of the executive committee of the Jewish Agency, a role he kept until the creation of the state of Israel in 1948.

During the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, Ben-Gurion instigated a policy of restraint ("Havlagah") in which the Haganah and other Jewish groups did not retaliate for Arab attacks against Jewish civilians, concentrating only on self-defense. In 1937, the Peel Commission recommended partitioning Palestine into Jewish and Arab areas and Ben-Gurion supported this policy.[14] This led to conflict with Ze'ev Jabotinsky who opposed partition and as a result Jabotinsky's supporters split with the Haganah and abandoned Havlagah.

The house where he lived from 1931 on, and for part of each year after 1953, is now a historic house museum in Tel Aviv, the "Ben-Gurion House". In 1946, Ben-Gurion and North Vietnam's Politburo chairman Ho Chi Minh became very friendly when they stayed at the same hotel in Paris. Ho Chi Minh offered Ben-Gurion a Jewish home-in-exile in Vietnam. Ben-Gurion declined, telling Ho Chi Minh: "I am certain we shall be able to establish a Jewish Government in Palestine."[15][16]

Views and opinions

Decisiveness and pragmatism

In Ben-Gurion: A Political Life by Shimon Peres and David Landau, Peres recalls his first meeting with Ben-Gurion as a young activist in the No'ar Ha'Oved youth movement. Ben-Gurion gave him a lift, and out of the blue told him why he preferred Lenin to Trotsky: "Lenin was Trotsky’s inferior in terms of intellect", but Lenin, unlike Trotsky, "was decisive". When confronted with a dilemma, Trotsky would do what Ben-Gurion despised about the old-style diaspora Jews: he manoeuvred; as opposed to Lenin, who would cut the Gordian knot, accepting losses while focusing on the essentials. In Peres' opinion, the essence of Ben-Gurion's life work were "the decisions he made at critical junctures in Israel’s history", and none was as important as the acceptance of the 1947 partition plan, a painful compromise which gave the emerging Jewish state little more than a fighting chance, but which, according to Peres, enabled the establishment of the State of Israel.[17]

Attitude towards Arabs

Ben-Gurion published two volumes setting out his views on relations between Zionists and the Arab world: We and Our Neighbors, published in 1931, and My Talks with Arab Leaders published in 1967. Ben-Gurion believed in the equal rights of Arabs who remained in and would become citizens of Israel. He was quoted as saying, "We must start working in Jaffa. Jaffa must employ Arab workers. And there is a question of their wages. I believe that they should receive the same wage as a Jewish worker. An Arab has also the right to be elected president of the state, should he be elected by all."[18]

Ben-Gurion recognized the strong attachment of Palestinian Arabs to the land and in an address to the United Nations on 2 October 1947, he doubted the likelihood of peace:

Esplanade Ben Gourion, Paris, near the Seine, in front of the Musée du Quai Branly

This is our native land; it is not as birds of passage that we return to it. But it is situated in an area engulfed by Arabic-speaking people, mainly followers of Islam. Now, if ever, we must do more than make peace with them; we must achieve collaboration and alliance on equal terms. Remember what Arab delegations from Palestine and its neighbors say in the General Assembly and in other places: talk of Arab-Jewish amity sound fantastic, for the Arabs do not wish it, they will not sit at the same table with us, they want to treat us as they do the Jews of Bagdad, Cairo, and Damascus.[19]

Nahum Goldmann criticized Ben-Gurion for what he viewed as a confrontational approach to the Arab world. Goldmann wrote, "Ben-Gurion is the man principally responsible for the anti-Arab policy, because it was he who molded the thinking of generations of Israelis."[20]Simha Flapan quoted Ben-Gurion as stating in 1938: "I believe in our power, in our power which will grow, and if it will grow agreement will come..."[21]

In 1909, Ben-Gurion attempted to learn Arabic but gave up. He later became fluent in Turkish. The only other languages he was able to use when in discussions with Arab leaders were English, and to a lesser extent, French.[22]

Attitude towards the British

The British 1939 White paper stipulated that Jewish immigration to Palestine was to be limited to 15,000 a year for the first five years, and would subsequently be contingent on Arab consent. Restrictions were also placed on the rights of Jews to buy land from Arabs. After this Ben-Gurion changed his policy towards the British, stating: "Peace in Palestine is not the best situation for thwarting the policy of the White Paper".[23] Ben-Gurion believed a peaceful solution with the Arabs had no chance and soon began preparing the Yishuv for war. According to Teveth 'through his campaign to mobilize the Yishuv in support of the British war effort, he strove to build the nucleus of a "Hebrew Army", and his success in this endeavor later brought victory to Zionism in the struggle to establish a Jewish state.'[24]

During the Second World War, Ben-Gurion encouraged the Jewish population to volunteer for the British Army. He famously told Jews to "support the British as if there is no White Paper and oppose the White Paper as if there is no war".[25] About 10% of the Jewish population of Palestine volunteered for the British Army, including many women. At the same time Ben-Gurion assisted the illegal immigration of thousands of European Jewish refugees to Palestine during a period when the British placed heavy restrictions on Jewish immigration.

In 1946, Ben-Gurion agreed that the Haganah could cooperate with Menachem Begin's Irgun in fighting the British, who continued to restrict Jewish immigration. Ben-Gurion initially agreed to Begin's plan to carry out the 1946 King David Hotel bombing, with the intent of embarrassing (rather than killing) the British military stationed there. However, when the risks of mass killing became apparent, Ben-Gurion told Begin to call the operation off. Begin refused.[26]

Due to the Jewish insurgency in Palestine, bad publicity over the restriction of Jewish immigrants to Palestine, non-acceptance of a partitioned state (as suggested by the United Nations) amongst Arabs residents, and the cost of keeping 100,000 troops in Palestine the British Government referred the matter to the United Nations. The British were against the partition plan and announced they would hand the Mandate over to the U.N. on 15 May 1948. However, on 14 May the Israeli Declaration of Independence was unilaterally declared, leading to the 1948 Palestinian exodus.

Attitude towards conquering West Bank

After the ten-day campaign during the 1948 war, the Israelis were militarily superior to their enemies and the Cabinet subsequently considered where and when to attack next.[27] On 24 September, an incursion made by the Palestinian irregulars in the Latrun sector (killing 23 Israeli soldiers) precipitated the debate. On 26 September, David Ben-Gurion put his argument to the Cabinet to attack Latrun again and conquer the whole or a large part of West Bank.[28][29][30][31] The motion was rejected by 5 votes to 7 after discussions.[31] Ben-Gurion qualified the cabinet's decision as bechiya ledorot ("a source of lament for generations") considering Israel may have lost forever the Old City of Jerusalem.[32][33][34]

There is a controversy around these events. According to Uri Bar-Joseph, Ben-Gurion placed a plan that called for a limited action aimed at the conquest of Latrun, and not for an all-out offensive. According to David Tal, in the cabinet meeting, Ben-Gurion reacted to what he had been just told by a delegation from Jerusalem. He points out that this view he would have planned to conquest West Bank is unsubstantiated in both Ben-Gurion's diary and in the Cabinet protocol.[35][36][37][38]

The topic came back at the end of the 1948 war, when General Yigal Allon also proposed the conquest of the West Bank up to the Jordan River as the natural, defensible border of the state. This time, Ben-Gurion refused although he was aware that the IDF was militarily strong enough to carry out the conquest. He feared the reaction of Western powers and wanted to maintain good relations with the United States and not to provoke the British. Moreover, in his opinion the results of the war were already satisfactory and Israeli leaders had to focus on the building of a nation.[39][40][41]

According to Benny Morris, "Ben-Gurion got cold feet during the war. (...). If [he] had carried out a large expulsion and cleansed the whole country -the whole Land of Israel, as far as the Jordan River. It may yet turn out that this was his fatal mistake. If he had carried out a full expulsion rather than a partial one- he would have stabilized the State of Israel for generations."[42]

Religious parties and status quo

In order to prevent the coalescence of the religious right, the Hisdadrut agreed to a vague "status quo" agreement with Mizrahi in 1935.

Ben-Gurion was aware that world Jewry could and would only feel comfortable to throw their support behind the nascent state, if it was shrouded with religious mystique. That would include an orthodox tacit acquiescence to the entity. Therefore, in September 1947 Ben-Gurion decided to reach a formal status quo agreement with the Orthodox Agudat Yisrael party. He sent a letter to Agudat Yisrael stating that while being committed to establishing a non-theocratic state with freedom of religion, he promised that the Shabbat would be Israel's official day of rest, that in state-provided kitchens there would be access to Kosher food, that every effort would be made to provide a single jurisdiction for Jewish family affairs, and that each sector would be granted autonomy in the sphere of education, provided minimum standards regarding the curriculum be observed.[43]

To a large extent this agreement provided the framework for religious affairs in Israel till the present day, and is often used as a benchmark regarding the arrangement of religious affairs in Israel.

Ben-Gurion also described himself as an irreligious person who developed atheism in his youth and who demonstrated no great sympathy for the elements of traditional Judaism, though he quoted the Bible extensively in his speeches and writings.[44] Modern Orthodox philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz considered Ben-Gurion "to have hated Judaism more than any other man he had met".[45]

In later time, Ben-Gurion refused to define himself as "secular", and he regarded himself a believer in God. In a 1970 interview, he described himself as a pantheist, and stated that "I don't know if there's an afterlife. I think there is."[46] During an interview with the Leftist weekly Hotam two years before his death, he revealed, "I too have a deep faith in the Almighty. I believe in one God, the omnipotent Creator. My consciousness is aware of the existence of material and spirit ... [But] I cannot understand how order reigns in nature, in the world and universe – unless there exists a superior force. This supreme Creator is beyond my comprehension . . . but it directs everything."[47]

In a letter to the writer Eliezer Steinman, he wrote "Today, more than ever, the 'religious' tend to relegate Judaism to observing dietary laws and preserving the Sabbath. This is considered religious reform. I prefer the Fifteenth Psalm, lovely are the psalms of Israel. The Shulchan Aruch is a product of our nation's life in the Exile. It was produced in the Exile, in conditions of Exile. A nation in the process of fulfilling its every task, physically and spiritually ... must compose a 'New Shulchan'--and our nation's intellectuals are required, in my opinion, to fulfill their responsibility in this."[47]

Military leadership

David Ben-Gurion visits 101 Squadron, the "First Fighter Squadron".

During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War Ben-Gurion oversaw the nascent state's military operations. During the first weeks of Israel's independence, he ordered all militias to be replaced by one national army, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). To that end, Ben-Gurion used a firm hand during the Altalena Affair, a ship carrying arms purchased by the Irgun led by Menachem Begin. He insisted that all weapons be handed over to the IDF. When fighting broke out on the Tel Aviv beach he ordered it be taken by force and to shell the ship. Sixteen Irgun fighters and three IDF soldiers were killed in this battle. Following the policy of a unified military force, he also ordered that the Palmach headquarters be disbanded and its units be integrated with the rest of the IDF, to the chagrin of many of its members. By absorbing the Irgun force into Israel's IDF, the Israelis eliminated competition and the central government controlled all military forces within the country. His attempts to reduce the number of Mapam members in the senior ranks led to the "Generals' Revolt" in June 1948.

As head of the Jewish Agency from 1935, Ben-Gurion was de facto leader of Jewish population even before the state was declared. In this position, Ben-Gurion played a major role in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War When the IDF archives and others were opened in the late 1980s, scholars started to reconsider the events and the role of Ben-Gurion.[48][clarification needed]

Founding of Israel

David Ben-Gurion with Yigal Allon and Yitzhak Rabin in the Negev, during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.

David Ben-Gurion proclaiming independence beneath a large portrait of Theodor Herzl, founder of modern Zionism

On 14 May 1948, on the last day of the British Mandate, Ben-Gurion declared the independence of the state of Israel. In the Israeli declaration of independence, he stated that the new nation would "uphold the full social and political equality of all its citizens, without distinction of religion, race".

In his War Diaries in February 1948, Ben-Gurion wrote: "The war shall give us the land. The concepts of 'ours' and 'not ours' are peace concepts only, and they lose their meaning during war."[49] Also later he confirmed this by stating that, "In the Negev we shall not buy the land. We shall conquer it. You forget that we are at war."[49] The Arabs, meanwhile, also vied with Israel over the control of territory by means of war, while the Jordanian Arab Legion had decided to concentrate its forces in Bethlehem and in Hebron in order to save that district for its Arab inhabitants, and to prevent territorial gains for Israel.[50] Israeli historian Benny Morris has written of the massacres of Palestinian Arabs in 1948, and has stated that Ben-Gurion "covered up for the officers who did the massacres."[51]

Ben-Gurion on the cover of Time (August 16, 1948)

After leading Israel during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Ben-Gurion was elected Prime Minister of Israel when his Mapai (Labour) party won the largest number of Knesset seats in the first national election, held on 14 February 1949. He would remain in that post until 1963, except for a period of nearly two years between 1954 and 1955. As Prime Minister, he oversaw the establishment of the state's institutions. He presided over various national projects aimed at the rapid development of the country and its population: Operation Magic Carpet, the airlift of Jews from Arab countries, the construction of the National Water Carrier, rural development projects and the establishment of new towns and cities. In particular, he called for pioneering settlement in outlying areas, especially in the Negev. Ben-Gurion saw the struggle to make the Negev desert bloom as an area where the Jewish people could make a major contribution to humanity as a whole.[52] He believed that the sparsely populated and barren Negev desert offered a great opportunity for the Jews to settle in Palestine with minimal obstruction of the Arab population,[dubious ] and set a personal example by settling in kibbutz Sde Boker at the centre of the Negev.[52]

During this period, Palestinian fedayeen repeatedly infiltrated into Israel from Arab territory. In 1953, after a handful of unsuccessful retaliatory actions, Ben-Gurion charged Ariel Sharon, then security chief of the northern region, with setting up a new commando unit designed to respond to fedayeen infiltrations. Ben-Gurion told Sharon, "The Palestinians must learn that they will pay a high price for Israeli lives." Sharon formed Unit 101, a small commando unit answerable directly to the IDF General Staff tasked with retaliating for fedayeen raids. During its five months of existence, the unit launched repeated raids against military targets and villages used as bases by the fedayeen.[53] These attacks became known as the reprisal operations.

U.S. President Harry S. Truman in the Oval Office, receiving a Menorah as a gift from the Prime Minister of Israel, David Ben-Gurion (center). To the right is Abba Eban, the Ambassador of Israel to the United States.

In 1953, Ben-Gurion announced his intention to withdraw from government and was replaced by Moshe Sharett, who was elected the second Prime Minister of Israel in January 1954. However, Ben-Gurion temporarily served as acting prime minister when Sharett visited the United States in 1955. During Ben-Gurion's tenure as acting prime minister, the IDF carried out Operation Olive Leaves, a successful attack on fortified Syrian emplacements near the northeastern shores of the Sea of Galilee. The operation was a response to Syrian attacks on Israeli fishermen. Ben-Gurion had ordered the operation without consulting the Israeli cabinet and seeking a vote on the matter, and Sharett would later bitterly complain that Ben-Gurion had exceeded his authority.[54]

Ben-Gurion returned to government in 1955. He assumed the post of Defense Minister and was soon re-elected prime minister. When Ben-Gurion returned to government, Israeli forces began responding more aggressively to Egyptian-sponsored Palestinian guerilla attacks from Gaza—still under Egyptian rule. Egypt's President Gamal Abdel Nasser signed the Egyptian-Czech arms deal and purchased a large amount of modern arms. The Israelis responded by arming themselves with help from France. Nasser blocked the passage of Israeli ships through the Straits of Tiran and the Suez Canal. In July 1956, the United States and Britain withdrew their offer to fund the Aswan High Dam project on the Nile and a week later, Nasser ordered the nationalization of the French and British-controlled Suez Canal. In late 1956, the bellicosity of statements Arab prompted Israel to remove the threat of the concentrated Egyptian forces in the Sinai, and Israel invaded the Egyptian Sinai peninsula. Other Israeli aims were elimination of the Fedayeen incursions into Israel that made life unbearable for its southern population, and opening the blockaded Straits of Tiran for Israeli ships.[55][56][57][58][59][60] Israel occupied much of the peninsula within a few days. As agreed beforehand, within a couple of days, Britain and France invaded too, aiming at regaining Western control of the Suez Canal and removing the Egyptian president Nasser. The United States pressure forced the British and French to back down and Israel to withdraw from Sinai in return for free Israeli navigation through the Red Sea. The United Nations responded by establishing its first peacekeeping force, (UNEF). It was stationed between Egypt and Israel and for the next decade it maintained peace and stopped the Fedayeen incursions into Israel.

David Ben-Gurion speaking at the Knesset, 1957

In 1959, David Ben-Gurion learned from West German officials of reports that the notorious Nazi war criminal, Adolf Eichmann, was likely living in hiding in Argentina. In response, Ben-Gurion ordered the Israel foreign intelligence service, the Mossad, to capture the international fugitive alive for trial in Israel. In 1960, this mission was accomplished and Eichmann was tried and convicted in an internationally publicized trial for various offenses including crimes against humanity, and was subsequently executed in 1962.

Ben-Gurion is said to have been "nearly obsessed" with Israel obtaining nuclear weapons, feeling that a nuclear arsenal was the only way to counter the Arabs' superiority in numbers, space, and financial resources, and that it was the only sure guarantee of Israel's survival and the prevention of another Holocaust.[61]

Ben-Gurion stepped down as prime minister for personal reasons in 1963, and chose Levi Eshkol as his successor. A year later a rivalry developed between the two on the issue of the Lavon Affair, a failed 1954 Israeli covert operation in Egypt. Ben-Gurion had insisted that the operation be properly investigated, while Eshkol refused. Ben-Gurion subsequently broke with Mapai in June 1965 and formed a new party, Rafi, while Mapai merged with Ahdut HaAvoda to form Alignment, with Eshkol as its head. Alignment defeated Rafi in the November 1965 election, establishing Eshkol as the country's leader.

Later political career

In May 1967, Egypt began massing forces in the Sinai Peninsula after expelling UN peacekeepers and closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping. This, together with the actions of other Arab states, caused Israel to begin preparing for war. The situation lasted until the outbreak of the Six-Day War on 5 June. In Jerusalem, there were calls for a national unity government or an emergency government. During this period, Ben-Gurion met with his old rival Menachem Begin in Sde Boker. Begin asked Ben-Gurion to join Eshkol's national unity government. Although Eshkol's Mapai party initially opposed the widening of its government, it eventually changed its mind.[62] On 23 May, IDF Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin met with Ben-Gurion to ask for reassurance. Ben-Gurion, however, accused Rabin of putting Israel in mortal danger by mobilizing the reserves and openly preparing for war with an Arab coalition. Ben-Gurion told Rabin that at the very least, he should have obtained the support of a foreign power, as he had done during the Suez Crisis. Rabin was shaken by the meeting and took to bed for 36 hours.[citation needed]

After the Israeli government decided to go to war, planning a preemptive strike to destroy the Egyptian Air Force followed by a ground offensive, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan told Ben-Gurion of the impending attack on the night of 4–5 June. Ben-Gurion subsequently wrote in his diary that he was troubled by Israel's impending offensive. On 5 June, the Six-Day War began with Operation Focus, an Israeli air attack that decimated the Egyptian air force. Israel then captured the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Egypt, the West Bank, including East Jerusalem from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria in a series of campaigns. Following the war, Ben-Gurion was in favour of returning all the captured territories apart from East Jerusalem, the Golan Heights and Mount Hebron as part of a peace agreement.[63]

On 11 June, Ben-Gurion met with a small group of supporters in his home. During the meeting, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan proposed autonomy for the West Bank, the transfer of Gazan refugees to Jordan, and a united Jerusalem serving as Israel's capital. Ben-Gurion agreed with him, but foresaw problems in transferring Palestinian refugees from Gaza to Jordan, and recommended that Israel insist on direct talks with Egypt, favoring withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula in exchange for peace and free navigation through the Straits of Tiran. The following day, he met with Jerusalem mayor Teddy Kollek in his Knesset office. Despite occupying a lower executive position, Ben-Gurion treated Kollek like a subordinate.[64]

Following the Six-Day War, Ben-Gurion criticized what he saw as the government's apathy towards the construction and development of the city. To ensure that a united Jerusalem remained in Israeli hands, he advocated a massive Jewish settlement program for the Old City and the hills surrounding the city, as well as the establishment of large industries in the Jerusalem area to attract Jewish migrants. He argued that no Arabs would have to be evicted in the process.[64] Ben-Gurion also urged extensive Jewish settlement in Hebron.

In 1968, when Rafi merged with Mapai to form the Alignment, Ben-Gurion refused to reconcile with his old party. He favoured electoral reforms in which a constituency-based system would replace what he saw as a chaotic proportional representation method. He formed another new party, the National List, which won four seats in the 1969 election.

Final years and death

Graves of Paula and David Ben-Gurion, Midreshet Ben-Gurion

Ben-Gurion retired from politics in 1970 and spent his last years living in a modest home on the kibbutz, working on an 11-volume history of Israel's early years. In 1971, he visited Israeli positions along the Suez Canal during the War of Attrition.

On 18 November 1973, Ben-Gurion suffered a cerebral hemorrhage, and was taken to Sheba Medical Center in Tel HaShomer, Ramat Gan. During the first week following the stroke, he received visits from many high-ranking officials, including Prime Minister Golda Meir. His condition began deteriorating on 23 November, and he died on 1 December at age 87. His stroke and death took place during the immediate aftermath of the Yom Kippur War. As he was dying, his grandson Alon, who fought as a paratrooper in the war, was also hospitalized for shrapnel wounds sustained in combat.[65] His body lay in state in the Knesset compound before being flown by helicopter to Sde Boker. Sirens sounded across the entire country to mark his death. He was buried in a simple funeral alongside his wife Paula at Midreshet Ben-Gurion.

Awards

- In 1949, Ben-Gurion was awarded the Solomon Bublick Award of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, in recognition of his contributions to the State of Israel.[66]

- In both 1951 and 1971, he was awarded the Bialik Prize for Jewish thought.[67]

Commemoration

Sculpture of David Ben-Gurion at Ben Gurion Airport, named in his honor

- Israel's largest airport, Ben Gurion International Airport, is named in his honor.

- One of Israel's major universities, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, located in Beersheva, is named after him.

- Numerous streets, as well as schools, throughout Israel have been named after him.

- An Israeli modification of the British Centurion Tank was named after Ben-Gurion

Ben-Gurion's Hut in Kibbutz Sde Boker which is now a visitor's center.- A desert research center, Midreshet Ben-Gurion, near his "hut" in Kibbutz Sde Boker has been named in his honor. Ben-Gurion's grave is in the research center.

- An English Heritage blue plaque, unveiled in 1986, marks where Ben-Gurion lived in London at 75 Warrington Crescent, Maida Vale, W9.[68]

- Is also a chapter in the Pacific Coast Region of The B'nai B'rith Youth Organization in Pomona, California.

- In the 7th arrondissement of Paris, part of a riverside promenade of the Seine is named after him.[69]

- His portrait appears on both the 500 lirot[70] and the 50 (old) sheqalim notes issued by the Bank of Israel.[71]

See also

- List of Bialik Prize recipients

- Jewish Agency for Israel

- Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany

References

^ Brenner, Michael; Frisch, Shelley (April 2003). Zionism: A Brief History. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 184.|access-date=requires|url=(help).mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ "1973: Israel's founding father dies". 1 December 1973. Retrieved 31 August 2018 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

^ George Lavy, Germany and Israel: moral debt and national interest (1996) p. 45

^ "Avotaynu: The International Review of Jewish Genealogy". G. Mokotoff. 31 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018 – via Google Books.

^ "Ben-Gurion may have been a twin". Haaretz.

^

Memoirs : David Ben-Gurion (1970), p. 36.

^ Teveth, Shabtai (1985) Ben-Gurion and the Palestinian Arabs. From Peace to War. Oxford University Press.

ISBN 0-19-503562-3. Ezra – pp. 3, 4; Paolei Zion – p. 6; central committee – p. 9; populations—pp. 10, 21; Galilee pp. 12, 14–15.

^ Oswego.edu, Gila Hadar, "Space and Time in Salonika on the Eve of World War II and the Expulsion and Extermination of Salonika Jewry", Yalkut Moseshet 4, Winter 2006

^ Teveth, Shabtai (1985) Ben-Gurion and the Palestinian Arabs. From Peace to War. Oxford University Press.

ISBN 0-19-503562-3. pp. 25, 26.

^ ab "Mary Ben-Gurion (biographical details)". cosmos.ucc.ie. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

^ "Amos Ben-Gurion (biographical details)". cosmos.ucc.ie. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

^ Beckerman, Gal (29 May 2006). "The apples sometimes fall far from the tree". The Jerusalem Post.

^ Teveth, Shabtai (1985) Ben-Gurion and the Palestinian Arabs. From Peace to War. Oxford University Press.

ISBN 0-19-503562-3. pp. 66–70

^ Morris, Benny (3 October 2002). "Two years of the intifada – A new exodus for the Middle East?". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

^ "Ben-gurion Reveals Suggestion of North Vietnam's Communist Leader". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 8 November 1966. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

^ "ISRAEL WAS EVERYTHING". Nytimes.com. 21 June 1987. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

^ "Secrets of Ben-Gurion's Leadership". Forward.com. Retrieved 2015-05-17.

^ Efraim Karsh, "Fabricating Israeli history: the 'new historians'", Edition 2, Routledge, 2000,

ISBN 978-0-7146-5011-1, p. 213.

^ David Ben-Gurion, statement to the Assembly of Palestine Jewry, 2 October 1947

^ Nahum Goldmann, The Jewish Paradox A Personal Memoir, translated by Steve Cox, 1978,

ISBN 0-448-15166-9, pp. 98, 99, 100

^ Simha Flapan, Zionism and the Palestinians, 1979,

ISBN 0-85664-499-4, pp. 142–144

^ Teveth, Shabtai (1985) Ben-Gurion and the Palestinian Arabs. From Peace to War. Oxford University Press.

ISBN 0-19-503562-3. p. 118.

^ Shabtai Teveth, 1985, Ben-Gurion and the Palestinian Arabs, p. 199

^ S. Teveth, 1985, Ben-Gurion and the Palestinian Arabs, p. 200

^ "Ben-Gurion's road to the State" (in Hebrew). Ben-Gurion Archives. Archived from the original on 15 February 2006.

^ Paul Johnson, A History of the Jews, p. 523.

^ Benny Morris (2008), pp. 315–316.

^ Benny Morris (2008), pp. 317.

^ Uri Ben-Eliezer, The Making of Israeli Militarism, Indiana University Press, 1998, p.185 writes: "Ben-Gurion describes to the Minister his plans to conquer the entire West Bank, involving warfare against entire Jordan's Arab Legion, but to his surprise the Ministers rejected his proposal."

^ "Ben Gurion proposal to conquer Latrun, the cabinet meeting, 26 sept 1948 (hebrew)". Israel state archive blog:. israelidocuments.blogspot.co.il/2015/02/1948.html (Hebrew).

^ ab Benny Morris (2008), p. 318.

^ Mordechai Bar-On, Never-Ending Conflict: Israeli Military History, Stackpole Books, 2006, p.60 writes : "Originally, this was an idiom that Ben-Gurion used after the government rejected his demand to attack the Legion and occupy Samaria in the wake of a Mujuhidin's attack near Latrun in September 1948.

^ Yoav Gelber, Israeli-Jordanian Dialogue, 1948–1953, Sussex Academic Press, 2004, p.2.

^ Benny Morris (2008), pp. 315.

^ Zaki Shalom (2002). David Ben-Gurion, the State of Israel and the Arab World, 1949–1956. Sussex Academic Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-902210-21-6.A great satisfaction with the armistice borders…(Concerning the) area intended to pass into Israeli…(Ben Gurions') statements reveal the ambiguity over this subject

^ Zaki Shalom (2002). David Ben-Gurion, the State of Israel and the Arab World, 1949–1956. Sussex Academic Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-902210-21-6.If BG had been fully convinced that the IDF should have fought more aggressively for Jerusalem and the surrounding area, then Sharet's opposition would not have stood in the way of government consent

^ David Tal (24 June 2004). War in Palestine, 1948: Israeli and Arab Strategy and Diplomacy. Routledge. pp. 406–407. ISBN 978-1-135-77513-1.Nothing of this sort appears in the diary he kept at the time or in the minutes of the Cabinet meeting from which he is ostensibly quoting... Ben Gurion once more raised the idea of conquering Latrun in the cabinet. Ben Gurion was in fact reacting to what he had been told by a delegation from Jerusalem... The "everlasting shame" view is unsubstantiated in both Ben Gurion's diary and in the Cabinet protocol.

^ Uri Bar-Joseph (19 December 2013). The Best of Enemies: Israel and Transjordan in the War of 1948. Routledge. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-135-17010-3.the plan place by BG before the government call not for an all-out offensive, but rather for a limited action aimed at the conquest of Latrun…more than 13 years later ..(he) claim that his proposal had been far more comprehensive

^ Anita Shapira (25 November 2014). Ben-Gurion: Father of Modern Israel. Yale University Press. pp. 173–. ISBN 978-0-300-18273-6."(Ben Gurion) He also did not flinch from provoking the United Nations by breaking the truce agreement. But the limit of his fearlessness was a clash with a Western power. Vainly, the right and Mapam accused him of defeatism. He did not flinch from confronting them but chose to maintain good relations with the United States, which he perceived as a potential ally of the new state, and also not to provoke the British lion, even though its fangs had been drawn. At the end of the war, when Yigal Allon, who represented the younger generation of commanders that had grown up in the war, demanded the conquest of the West Bank up to the Jordan River as the natural, defensible border of the state, Ben-Gurion refused. He recognized that the IDF was militarily strong enough to carry out the conquest, but he believed that the young state should not bite off more than it had already chewed. There was a limit to what the world was prepared to accept. Furthermore, the armistice borders—which later became known as the Green Line—were better than those he had dreamed of at the beginning of the war. In Ben-Gurion's opinion, in terms of territory Israel was satisfied. It was time to send the troops home and start work on building the new nation.

^ Benny Morris (2009). One state, two states: resolving the Israel/Palestine conflict. Yale University Press. p. 79.in March 1949, just before the signing of the Israel-Jordan armistice agreement, when IDF general Yigal Allon proposed conquering the West Bank, Ben-Gurion turned him down flat. Like most Israelis, Ben-Gurion had given up the dream

^ Zaki Shalom (2002). David Ben-Gurion, the State of Israel and the Arab World, 1949–1956. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 174–. ISBN 978-1-902210-21-6.The clearest expression of this 'activist' approach is found in a "personal, top secret" letter sent by Yigal Allon to BG shortly after ... We cannot imagine a border more stable than the Jordan River, which runs the entire length of the country

^ Ari Shavit, Survival of the fittest : An Interview with Benny Morris, Ha'aretz Friday Magazine, 9 January 2004.

^ The Status Quo Letter Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine., in Hebrew

^ "Biography: David Ben-Gurion: For the Love of Zion". www.vision.org. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

^ Michael Prior (12 November 2012). Zionism and the State of Israel: A Moral Inquiry. Routledge. pp. 293–. ISBN 978-1-134-62877-3. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

^ "The Free Lance-Star - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

^ ab Tsameret, Tsevi; Tlamim, Moshe (1 July 1999). "Judaism in Israel: Ben-Gurion's Private Beliefs and Public Policy". Israel Studies. 4 (2): 64–89. doi:10.1353/is.1999.0016. Retrieved 31 August 2018 – via Project MUSE.

^ See e.g. Benny Morris, the Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem and The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited

^ ab Mêrôn Benveniśtî, Sacred landscape: the buried history of the Holy Land since 1948, p. 120

^ Sir John Bagot Glubb, A Soldier with the Arabs, London 1957, p. 200

^ Ari Shavit'Survival of the fittest,' Haaretz 8 January 2004:"The worst cases were Saliha (70–80 killed), Deir Yassin (100–110), Lod (250), Dawayima (hundreds) and perhaps Abu Shusha (70). There is no unequivocal proof of a large-scale massacre at Tantura, but war crimes were perpetrated there. At Jaffa there was a massacre about which nothing had been known until now. The same at Arab al Muwassi, in the north. About half of the acts of massacre were part of Operation Hiram [in the north, in October 1948]: at Safsaf, Saliha, Jish, Eilaboun, Arab al Muwasi, Deir al Asad, Majdal Krum, Sasa. In Operation Hiram there was a unusually high concentration of executions of people against a wall or next to a well in an orderly fashion.That can't be chance. It's a pattern. Apparently, various officers who took part in the operation understood that the expulsion order they received permitted them to do these deeds in order to encourage the population to take to the roads. The fact is that no one was punished for these acts of murder. Ben-Gurion silenced the matter. He covered up for the officers who did the massacres."

^ ab David Ben-Gurion (17 January 1955). "Importance of the Negev" (in Hebrew). Archived from the original on 23 February 2007.

^ "Unit 101 (Israel) | Specwar.info ||". En.specwar.info. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

^ Vital (2001), p. 182

^ Moshe Shemesh; Selwyn Illan Troen (5 October 2005). The Suez-Sinai Crisis: A Retrospective and Reappraisal. Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-135-77863-7.The aims were to be threefold: to remove the threat, wholly or partially, of the Egyptian rmy in the Sinai, to destroy the framework of the fedaiyyun, and to secure the freedom of navigation through the straits of Tiran.

^ Isaac Alteras (1993). Eisenhower and Israel: U.S.-Israeli Relations, 1953–1960. University Press of Florida. pp. 192–. ISBN 978-0-8130-1205-6.the removal of the Egyptian blockade of the Straits of Tiran at the entrance of the Gulf of Aqaba. The blockade closed Israel’s sea lane to East Africa and the Far East, hindering the development of Israel’s southern port of Eilat and its hinterland, the Nege. Another important objective of the Israeli war plan was the elimination of the terrorist bases in the Gaza Strip, from which daily fedayeen incursions into Israel made life unbearable for its southern population. And last but not least, the concentration of the Egyptian forces in the Sinai Peninsula, armed with the newly acquired weapons from the Soviet bloc, prepared for an attack on Israel. Here, Ben-Gurion believed, was a time bomb that had to be defused before it was too late. Reaching the Suez Canal did not figure at all in Israel’s war objectives.

^ Dominic Joseph Caraccilo (January 2011). Beyond Guns and Steel: A War Termination Strategy. ABC-CLIO. pp. 113–. ISBN 978-0-313-39149-1.The escalation continued with the Egyptian blockade of the Straits of Tiran, and Nasser's nationalization of the Suez Canal in July 1956. On October 14, Nasser made clear his intent:"I am not solely fighting against Israel itself. My task is to deliver the Arab world from destruction through Israel's intrigue, which has its roots abroad. Our hatred is very strong. There is no sense in talking about peace with Israel. There is not even the smallest place for negotiations." Less than two weeks later, on October 25, Egypt signed a tripartite agreement with Syria and Jordan placing Nasser in command of all three armies. The continued blockade of the Suez Canal and Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli shipping, combined with the increased fedayeen attacks and the bellicosity of recent Arab statements, prompted Israel, with the backing of Britain and France, to attack Egypt on October 29, 1956.

^ "The Jewish Virtual Library, The Sinai-Suez Campaign: Background & Overview".In 1955, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser began to import arms from the Soviet Bloc to build his arsenal for the confrontation with Israel. In the short-term, however, he employed a new tactic to prosecute Egypt's war with Israel. He announced it on August 31, 1955: Egypt has decided to dispatch her heroes, the disciples of Pharaoh and the sons of Islam and they will cleanse the land of Palestine....There will be no peace on Israel's border because we demand vengeance, and vengeance is Israel's death. These “heroes” were Arab terrorists, or fedayeen, trained and equipped by Egyptian Intelligence to engage in hostile action on the border and infiltrate Israel to commit acts of sabotage and murder.

^ Alan Dowty (20 June 2005). Israel/Palestine. Polity. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-0-7456-3202-5.Gamal Abdel Nasser, who declared in one speech that "Egypt has decided to dispatch her heroes, the disciples of Pharaoh and the sons of Islam and they will cleanse the land of Palestine....There will be no peace on Israel's border because we demand vengeance, and vengeance is Israel's death."...The level of violence against Israelis, soldiers and civilians alike, seemed to be rising inexorably.

^ Ian J. Bickerton (15 September 2009). The Arab-Israeli Conflict: A History. Reaktion Books. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-86189-527-1.(p. 101) To them the murderous fedayeen raids and constant harassment were just another form of Arab warfare against Israel...(p. 102) Israel's aims were to capture the Sinai peninsula in order to open the straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping, and to seize the Gaza strip to end fedayeen attacks.

^ Zaki Shalom, Israel's Nuclear Option: Behind the Scenes Diplomacy Between Dimona and Washington, (Portland, Ore.: Sussex Academic Press, 2005), p. 44

^ "The Six Day War – May 1967, one moment before – Israel News, Ynetnews". Ynetnews.com. 20 June 1995. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

^ Randolph Churchill, Winston Churchill, The Six Day War, 1967 p. 199 citing The World at One, BBC radio, 12 July 1967

^ ab Shalom, Zaki: Ben-Gurion's political struggles, 1963–1967

^ The Evening Independent (1 December 1973 issue)

^ "Ben Gurion Receives Bublick Award; Gives It to University As Prize for Essay on Plato" (10 August 1949). Jewish Telegraphic Agency. www.jta.org. Retrieved 2016-07-01.

^ "List of Bialik Prize recipients 1933–2004" (PDF) (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv Municipality website. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2007.

^ "BEN-GURION, DAVID (1886–1973)". English Heritage. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

^ Byron, Joseph (15 May 2010). "Paris Mayor inaugurates David Ben-Gurion esplanade along Seine river, rejects protests". European Jewish Press. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

^ "BANKNOTE COLLECTION". Banknote.ws. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

^ "BANKNOTE COLLECTION". Banknote.ws. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

Further reading

Aronson, Shlomo (2011). David Ben-Gurion and the Jewish Renaissance. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19748-9..- Cohen, Mitchell (1987/1992). "Zion and State: Nation, Class and the Shaping of Modern Israel" Columbia University Press)

- Peres, Shimon (2011). Ben-Gurion, Schocken Pub.,

ISBN 978-0-8052-4282-9.

Teveth, Shabtai (1985). Ben-Gurion and the Palestinian Arabs: from peace to war. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503562-9.

Teveth, Shabtai (1996). Ben-Gurion and the Holocaust. Harcourt Brace & Co.

Teveth, Shabtai (1997). The Burning Ground. A biography of David Ben-Gurion. Schoken, Tel Aviv.- St. John, Robert William (1961), Builder of Israel; the story of Ben-Gurion, Doubleday

- Shilon, Avi (2013), Ben-Gurion, Epilogue, Am-Oved Publishers,

ISBN 978-965-13-2391-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to David Ben Gurion. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: David Ben-Gurion |

Wikisource has original works written by or about: David Ben-Gurion |

David Ben-Gurion on the Knesset website

Special Report David Ben-Gurion BBC News

"David Ben-Gurion (1886–1973)" Jewish Agency for Israel

David Ben-Gurion's Personal Correspondence and Historical Documents Shapell Manuscript Foundation- Annotated bibliography for David Ben-Gurion from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- March 2011 Ben-Gurion and Tewfik Toubi Finally Meet (28 October 1966)

- David Ben-Gurion Personal Manuscripts

Newspaper clippings about David Ben-Gurion in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by (none) | Chairman, Provisional State Council 14–16 May 1948 | Succeeded by Chaim Weizmann |

New office | Prime Minister of Israel 1948–1954 | Succeeded by Moshe Sharett |

| Preceded by Moshe Sharett | Prime Minister of Israel 1955–1963 | Succeeded by Levi Eshkol |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by (none) | Leader of Mapai 1948–1954 | Succeeded by Moshe Sharett |

| Preceded by Moshe Sharett | Leader of Mapai 1955–1963 | Succeeded by Levi Eshkol |

| Preceded by new party | Leader of Rafi 1965–1968 | Succeeded by ceased to exist |

| Preceded by new party | Leader of the National List 1968–1970 | Succeeded by Yigael Hurvitz |