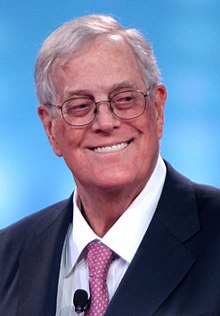

David Koch

David Koch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | David Hamilton Koch (1940-05-03) May 3, 1940 Wichita, Kansas, U.S. |

| Education | Massachusetts Institute of Technology (BS, MS) |

| Occupation | Vice President of Koch Industries |

| Known for | Philanthropy to cultural and medical institutions Support of libertarian and conservative causes[1][2] |

| Net worth | US$50.2 billion (June 2018) |

| Political party | Libertarian (before 1984) Republican (1984–present) |

| Board member of | Aspen Institute, Cato Institute, Reason Foundation, Americans for Prosperity Foundation, WGBH, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, American Ballet Theatre, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, Deerfield Academy, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, American Museum of Natural History |

| Spouse(s) | Julia Flesher (m. 1996) |

| Children | 3 |

| Parent(s) | Fred C. Koch Mary Robinson |

| Relatives | Frederick R. Koch (brother) Charles Koch (brother) Bill Koch (twin brother) |

David Hamilton Koch (/koʊk/; born May 3, 1940) is an American businessman, philanthropist, political activist, and chemical engineer. He joined the family business Koch Industries, the second-largest privately held company in the United States, in 1970. He became president of the subsidiary Koch Engineering in 1979, and became a co-owner of Koch Industries, with older brother Charles, in 1983. He served as an executive vice president until his retirement in 2018.[3] Upon retirement in June 2018 due to health issues, Koch received the title of Director Emeritus. Koch is an influential libertarian. He was the 1980 candidate for Vice President of the United States from the United States Libertarian Party and helped finance the campaign. He founded Citizens for a Sound Economy.[4] He and his brother Charles have donated to political advocacy groups[2] and to political campaigns, almost entirely Republican.[5] As of June 2018, he was ranked as the 12th-richest person in the world, (tied with his brother Charles), with a fortune of $50.7 billion.[6]

Condé Nast Portfolio described him as "one of the most generous but low-key philanthropists in America".[7] Koch has contributed to several charities including Lincoln Center, Sloan Kettering, New York-Presbyterian Hospital and the Dinosaur Wing at the American Museum of Natural History.[4] The New York State Theater at Lincoln Center, home of the New York City Ballet, was renamed the David H. Koch Theater in 2008 following a gift of $100 million for the renovation of the theater. Koch was the fourth richest person in the US as of 2012, and the wealthiest resident of New York City as of 2013.[8] He is a survivor of the USAir Flight 1493 crash in 1991.

Contents

1 Early life and education

2 Career at Koch Industries

3 Political career

4 Politics

4.1 Political views

4.2 Political advocacy

5 Philanthropy

5.1 Medical research

5.2 Arts

5.3 Education

5.4 Prison reform

6 Criticism and recognition

7 Personal life

8 See also

9 References

10 External links

Early life and education

Koch was born in Wichita, Kansas, the son of Mary Clementine (née Robinson) and Fred Chase Koch, a chemical engineer. David's paternal grandfather, Harry Koch, was a Dutch immigrant who founded the Quanah Tribune-Chief newspaper and was a founding shareholder of Quanah, Acme and Pacific Railway.[9] David is the third of four sons, with elder brothers Frederick R. Koch, Charles Koch, and nineteen-minute younger twin[10]Bill Koch. Among his maternal great-great-grandparents were William Ingraham Kip, an Episcopalian bishop, William Burnet Kinney, a politician, and Elizabeth Clementine Stedman, a writer.

Koch attended the Deerfield Academy prep school in Massachusetts, graduating in 1959. He went on to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), earning both a bachelor's (1962) and a master's degree (1963) in chemical engineering. He is a member of the Beta Theta Pi Fraternity. Koch played basketball at MIT, averaging 21 points per game at MIT over three years, a school record. He also held the single-game scoring record of 41 points from 1962 until 2009, when it was eclipsed by Jimmy Bartolotta.[10]

Career at Koch Industries

In 1970, Koch joined Koch Industries under his brother Charles, to work as a technical-services manager. He founded the company's New York office and in 1979 he became the president of his own division, Koch Engineering, renamed Chemical Technology Group. In 1985, Koch Industries was sued by Bill Koch and Frederick R. Koch for the first time in a long series of lawsuits about ownership, that lasted until 2001. As of 2010, David Koch owned 42 percent of Koch Industries, as does his brother Charles.[2] He holds 4 U.S patents.

On June 5, 2018, the company announced his retirement from the company due to declining health issues.[11]

Political career

Koch was the Libertarian Party's vice-presidential candidate in the 1980 presidential election,[12] sharing the party ticket with presidential candidate Ed Clark. The Clark–Koch ticket promised to abolish Social Security, the Federal Reserve Board, welfare, minimum-wage laws, corporate taxes, all price supports and subsidies for agriculture and business, and U.S. Federal agencies including the SEC, EPA, ICC, FTC, OSHA, FBI, CIA, and DOE.[1][13] The ticket received 921,128 votes, 1% of the total nationwide vote,[14] the Libertarian Party national ticket's best showing until 2016 in terms of percentage and its best showing in terms of raw votes until the 2012 presidential election, although that number was surpassed again in 2016.[15][16] "Compared to what [the Libertarians had] gotten before," Charles said, "and where we were as a movement or as a political/ideological point of view, that was pretty remarkable, to get 1 percent of the vote."[17]

After the bid, according to journalist Brian Doherty's Radicals for Capitalism, Koch viewed politicians as "actors playing out a script".[1][18]

Koch credits the campaign of Roger MacBride as his inspiration for getting involved in politics:

Here was a great guy, advocating all the things I believed in. He wanted less government and taxes, and was talking about repealing all these victimless crime laws that accumulated on the books. I have friends who smoke pot. I know many homosexuals. It's ridiculous to treat them as criminals—and here was someone running for president, saying just that.[13]

Koch gave his own Vice Presidential campaign $100,000 a month after being chosen as Ed Clark's running mate. "We'd like to abolish the Federal Elections Commission and all the limits on campaign spending anyway," Koch said in 1980. When asked why he ran, he replied: "Lord knows I didn't need a job, but I believe in what the Libertarians are saying. I suppose if they hadn't come along, I could have been a big Republican from Wichita. But hell—everybody from Kansas is a Republican."[13]

In 1984 he broke with the Libertarian Party when it supported eliminating all taxes. Since then, Koch has been a Republican.[2]:4

Politics

Political views

Koch considers himself a social liberal,[19] supporting women's right to choose,[20]gay rights, same-sex marriage and stem-cell research.[2][21] He opposes the war on drugs.[22] Koch supports policies that promote individual liberty and free market principles, and supports reduced government spending.[23] Koch supports a non-interventionist foreign policy; "Pursuing a very aggressive foreign policy," he says, "is an extremely expensive endeavor for the U.S. government. The cost of maintaining a huge military force abroad is gigantic. It's so big it puts a severe strain on the U.S. economy, creating economic hardships here at home."[24] Koch opposed the Iraq War, saying that the war has "cost a lot of money and it's taken so many American lives", and "I question whether that was the right thing to do. In hindsight that looks like it was not a good policy".[17] In an impromptu interview with the blog ThinkProgress, he was quoted as saying he would like the new Republican Congress to "cut the hell out of spending, balance the budget, reduce regulations, and support business."[25] He is against the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act.[26] He is skeptical about anthropogenic global warming. He has said a warmer planet would be good because "Earth will be able to support enormously more people because a far greater land area will be available to produce food".[26]

Koch has many thoughts on several of President Obama's policies. An article from the Weekly Standard, detailing the "left's obsession" with the Koch brothers, quotes Koch stating that Obama is "the most radical president we've ever had as a nation ... and has done more damage to the free enterprise system and long-term prosperity than any president we've ever had."[27] Koch said that Obama's father's economic socialism, practiced in Kenya, explains why Obama has "sort of antibusiness and anti-free enterprise" influences.[17] Koch said that Obama is "scary", a "hardcore socialist" who is "marvelous at pretending to be something other than that."[28] Koch contributed to both Republicans and Democrats in 2012, with the majority of his contributions going to Republican candidates.[29]

Political advocacy

In 1984, Koch founded, served as Chairman of the board of directors of, and donated to the free-market Citizens for a Sound Economy (CSE). Richard H. Fink served as its first president.[17] Koch is Chairman of the Board and gave initial funding to the Americans for Prosperity Foundation and to a related advocacy organization, Americans for Prosperity. A Koch Industries spokesperson issued a press release stating "No funding has been provided by Koch companies, the Koch foundations, or Charles Koch or David Koch specifically to support the tea parties."[30][31] Koch was the top initial funder of the Americans for Prosperity Foundation at $850,000.[32][33] Koch said that he sympathizes with the Tea Party movement, but denies directly supporting it, stating: "I've never been to a tea party event. No one representing the tea party has ever even approached me."[2]

Koch sits on the board and donates to the libertarian Cato Institute and Reason Foundation.[1][2][34]

In February 2012, during the Wisconsin gubernatorial recall election, Koch said of Wisconsin governor Scott Walker, "We're helping him, as we should. We've gotten pretty good at this over the years. We've spent a lot of money in Wisconsin. We're going to spend more," and said that by "we" he meant Americans for Prosperity.[35][36][37][38][39]

Philanthropy

Koch established the David H. Koch Charitable Foundation.[40][41] Since 2006, the Chronicle of Philanthropy has listed Koch as one of the world's top 50 philanthropists.[42]

Medical research

Koch says that his biggest contributions go toward a "moon shot" campaign to finding the cure for cancer, according to his profile on Forbes.[8] Between 1998 and 2012, Koch contributed at least $395 million to medical research causes and institutions.[43]

Koch sits on the Board of Directors of the Prostate Cancer Foundation and has contributed $41 million to the foundation, including $5 million to a collaborative project in the field of nanotechnology.[44][45] Koch is the eponym of the David H. Koch Chair of the Prostate Cancer Foundation, a position currently held by Dr. Jonathan Simons.[46]

In 2006, he gave $20 million to Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore for cancer research. The building he financed was named the David H. Koch Cancer Research Building .[47]

In 2007, he contributed $100 million to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for the construction of a new 350,000-square-foot (33,000 m2) research and technology facility to serve as the home of the David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research,[48] Since joining the MIT Corporation in 1988, Koch has given a total of $185 million to MIT.[43] $15 million to New York-Presbyterian Hospital Weill Cornell Medical Center[49] and $30 million to the Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center in New York.[50]

In 2008, he donated $25 million to the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston to establish the David Koch Center for Applied Research in Genitourinary Cancers.[51]

In 2011 Koch gave $5 million to the House Ear Institute, in Los Angeles, to create a center for hearing restoration,[42] and $25 million to the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City[52][53]

In 2013, he gave $100 million to NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital, the largest philanthropic donation in its history, beginning a $2 billion campaign to conclude in 2019 for a new ambulatory care center and renovation the infrastructure of the hospital's five sites.[54]

In 2015, he committed $150 million to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York to build the David H. Koch Center for Cancer Care, which will be housed in a 23-story building in development between East 73rd and 74th Streets overlooking the FDR Drive. The center will combine state-of-the-art cancer treatment in an environment that supports patients, families, and caregivers. The building will include flexible personal and community spaces, educational offerings, and opportunities for physical exercise.[55]

Arts

In July 2008, Koch pledged $100 million over 10 years to renovate the New York State Theater in the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, now named in his honor [56] and pledged $10 million to renovate fountains outside the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[57]

Koch has been a trustee of the American Ballet Theatre for 25 years[58] and has contributed more than $6 million to the theater.[59] He also sits on the Board of Trustees of WGBH-TV,[60][61] which produces more than two-thirds of the nationally distributed programs broadcast by PBS.

Education

From 1982 to 2013, Koch contributed $18.6 million to WGBH Educational Foundation, including $10 million to the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) show Nova.[62][63] Koch is a contributor to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., including a $20 million gift to the American Museum of Natural History, creating the David H. Koch Dinosaur Wing and a contribution of $15 million to the National Museum of Natural History to create the new David H. Koch Hall of Human Origins, which opened on the museum's 100th anniversary of its location on the National Mall on March 17, 2010.[64] He also serves on the executive board of the Institute of Human Origins.[65] In 2012, Koch contributed US$35 million to the Smithsonian to build a new dinosaur exhibition hall at the National Museum of Natural History.[66][67]

Koch also financed the construction of the $68 million Koch Center for mathematics, science and technology at the Deerfield Academy, a highly selective independent, coeducational boarding school at Deerfield, Massachusetts,[68][non-primary source needed] and was named its first and only Lifetime Trustee.[68]

Koch gave $10 million to the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory [69] where he was honored with the Double Helix Medal for Corporate Leadership for supporting research that, "improves the health of people everywhere".[70][non-primary source needed]

Prison reform

In July 2015 David Koch and his brother were commended by both President Obama and activist Anthony Van Jones for their bipartisan efforts to reform the prison system in the United States.[71][72] For nearly ten years the Kochs have been advocating for several reforms within the criminal justice system which include reducing recidivism rates, simplifying the employment process for the rehabilitated, and defending private property from government seizures through asset forfeiture.[72][73] Allying with groups such as the ACLU, the Center for American Progress, Families Against Mandatory Minimums, the Coalition for Public Safety, and the MacArthur Foundation, the Kochs maintain the current prison system unfairly targets low-income and minority communities at the expense of the public budget.[72][74]

Criticism and recognition

In August 2010, Jane Mayer wrote an article in The New Yorker on the political spending of David and Charles Koch stating: "As their fortunes grew, Charles and David Koch became the primary underwriters of hard-line libertarian politics in America."[1] Mayer's article was criticized by conservatives for not enumerating the Kochs' charitable donations.[17][75] Mayer's article was also criticized by Koch Industries as using "psycho-biographic innuendo, unnamed sources, and half-truths".[76]

An opinion piece by journalist Yasha Levine in the New York Observer said Mayer's article failed to mention that the Kochs' "free market philanthropy belies the immense profit they have made from corporate welfare".[77]

Kimberly O. Dennis, president and chief executive officer of the Searle Freedom Trust,[78] said in 2010 that the Kochs are acting against their economic interest in promoting "getting government out of the business of running the economy. If they were truly interested in protecting their profits, they wouldn't be spending so much to shrink government; they'd be looking for a bigger slice of the pie for themselves. Their funding is devoted to promoting free-market capitalism, not crony capitalism."[79][non-primary source needed]

In 2011 Time included Charles and David Koch among the Time 100 of the year, for their involvement in supporting the Tea Party movement and the criticism they received from liberals.[80]

Personal life

Koch married Julia Flesher in 1996.[81][82] He has 3 children.[81][82]

In 1992, Koch was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He underwent radiation, surgery, and hormone therapy, but the cancer has returned every time. Koch has said he believes his experience with cancer has encouraged him to fund medical research.[17]

See also

- List of billionaires

References

^ abcde Mayer, Jane (August 30, 2010). "Covert Operations: The billionaire brothers who are waging a war against Obama". The New Yorker..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ abcdefg Goldman, Andrew (July 25, 2010). "The Billionaire's Party: David Koch is New York's second-richest man, a celebrated patron of the arts, and the tea party's wallet". New York magazine. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

^ [1] Archived February 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

^ ab Suzan Mazur, "The Altenberg 16: An Exposé of the Evolution Industry", North Atlantic Books, 2010, 343 pages

^ "Koch Industries: Summary". OpenSecrets.org. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

^ "David Koch". Retrieved June 5, 2018.

^ Weiss, Gary, "The Price of Immortality", Condé Nast Portfolio, November 2008.

^ ab "David Koch – Forbes". Forbes. March 9, 2011. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

^ "Koch, David Hamilton (1940)". New Netherland Project. Retrieved August 31, 2010.

^ ab "David and William Koch as MIT Basketball Players". The New Republic. August 14, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

^ Hohmann, James (June 5, 2018). "David Koch is leaving Koch Industries, stepping down from Americans for Prosperity". Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via www.washingtonpost.com.

^ Curtis, Charlotte (October 16, 1984). "Man Without a Candidate". The New York Times. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

^ abc Rinker Buck, "How Those Libertarians Pay the Bills", New York magazine, November 3, 1980

^ David Leip. "1980 Presidential General Election Results". uselectionatlas.org.

^ James T. Bennett, Not Invited to the Party: How the Demopublicans Have Rigged the System and Left Independents Out in the Cold, Springer, 2009, p. 167,

ISBN 1-4419-0365-8.

^ Confessore, Nicholas (May 17, 2014). "Quixotic '80 Campaign Gave Birth to Kochs' Powerful Network". The New York Times. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

^ abcdef Continetti, Matthew (April 4, 2011). "The Paranoid Style in Liberal Politics". The Weekly Standard.

^ Doherty, Brian (May 26, 2008). Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Movement. Perseus Books Group. p. 410. ISBN 978-1-58648-572-6. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

^ Bell, Benjamin (December 14, 2014). "Billionaire David Koch Says He's a Social Liberal". ABC News. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

^ Fischer, Sara (December 15, 2014). "David Koch is pro-choice, supports gay rights; just not Democrats". CNN. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

^ Joseph Patrick McCormick, Billionaire GOP supporter disagrees with platform, says he supports gay marriage, Pink News, September 2, 2012

^ The Koch Brothers December 24, 2012 p. 96 Forbes

^ Cooper, Michael (March 5, 2011). "Cancer Research Before Activism, Billionaire Conservative Donor Says". The New York Times.

^ "The New Antiwar Capitalists". Reason.com.

^ Fang, Lee (January 6, 2011). "Exclusive: Polluter Billionaire David Koch Says Tea Party 'Rank And File Are Just Normal People Like Us'". ThinkProgress.

^ ab "How Oil Heir and New York Arts Patron David Koch Became the Tea Party's Wallet". NYMag.com.

^ "The Paranoid Style in Liberal Politics". weeklystandard.com.

^ Owen, Sarah (May 5, 2011). "David Koch Gives President Obama Zero Credit for Bin Laden's Death". New York.

^ "Charts: How Much Have the Kochs Spent on the 2012 Election?". Mother Jones.

^ Jane Mayer (August 30, 2010). "Covert Operations". The New Yorker.

^ Weigel, David (April 15, 2010). "Dick Armey: Please, Koch, keep distancing yourself from me". Washington Post.

^ Seitz-Wald, Alex (September 24, 2013). "David Koch Seeded Major Tea-Party Group, Private Donor List Reveals". National Journal. Retrieved March 20, 2015.But a donor list filed with the IRS labeled "not open for public inspection" from 2003, the year of AFP's first filing, lists David Koch as by far the single largest contributor to its foundation, donating $850,000.

^ Levy, Pema (September 24, 2013). "Money In Politics: The Companies Behind David Koch's Americans For Prosperity". International Business Times. Retrieved March 20, 2015.David Koch was the top contributor, providing $850,000.

^ Sherman, Jake (August 20, 2009). "Conservatives Take a Page From Left's Online Playbook". The Wall Street Journal.

^ Singer, Stacey (February 20, 2012). "David Koch intends to cure cancer in his lifetime and remake American politics". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

^ Nichols, John (February 24, 2012). "Scott Walker's Koch Connection Goes Bad". The Nation. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

^ Kertscher, Tom (June 20, 2012). "Billionaire Koch brothers gave $8 million to Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker recall campaign, Dem chair says". PolitiFact. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

^ Kaufman, Dan (May 24, 2012). "How Did Wisconsin Become the Most Politically Divisive Place in America?". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

^ Spicuzza, Mary (February 20, 2012). "On Politics: David Koch: 'We've spent a lot of money in Wisconsin. We're going to spend more.'". Wisconsin State Journal. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

^ "David H. Koch Charitable Foundation and Personal Philanthropy". Koch Family Foundations. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

^ Levinthal, Dan (2015-10-30). "The Koch brothers' foundation network explained". The Center for Public Integrity. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

^ ab "No. 45: David H. Koch". The Chronicle of Philanthropy. The Chronicle of Philanthropy. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

^ ab Sparks, Evan (Summer 2012). "The Team Builder". Philanthropy Magazine. Retrieved September 26, 2012.

^ "David H. Koch – Prostate Cancer Foundation Nano-Medicine Gift Announced". PCF.org. October 12, 2007. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

^ Dolan, Kerry. "Warren Buffett Has Plenty Of Company Among Powerful In Battling Prostate Cancer". Forbes. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

^ "Clinical Data for World's First Truly Non-Invasive Prostate Cancer Test Published in JAMA Oncology". Businesswire. 2016-04-12. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

^ "David Koch Gives $20 Million for Hopkins Cancer Research". hopkinsmedicine.org.

^ "Empathy For Others" (PDF). Kochfamilyfoundations.org. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

^ Sally Beatty (October 9, 2007). "Institutional Gift, With a Catch". WSJ.

^ Beatty, Sally (October 9, 2007). "Institutional Gift, With a Catch". The Wall Street Journal.

^ [2] Archived April 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

^ "No. 45: David H. Koch". The Chronicle of Philanthropy. The Chronicle of Philanthropy. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

^ "Discovery to Recovery : Clinical and Research Highlights at HSS" (PDF). Joshfriedland.com. 2007. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

^ NewYork-Presbyterian (April 2, 2013). "NewYork-Presbyterian Announces $100 Million Donation from David H. Koch – Largest in Hospital's History – to Fund Outpatient Facility on Manhattan's East Side". Retrieved June 1, 2013.

^ "Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Receives Record Gift of $150 million from David Koch for Innovative Patient Care Facility". May 20, 2015. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

^ Pogrebin, Robin (July 10, 2008). "David H. Koch to Give 100 Million to Theater". The New York Times.

^ Souccar, Miriam Kreinin (June 27, 2010). "It's a Philanthropy Thing". Crains New York.

^ Donnelly, Shannon (June 2, 2010). "American Ballet Theatre Celebrates 70th Season, David Koch's Birthday". Palm Beach Daily News.

^ Cole, Patrick (May 17, 2010). "David Koch Toasted by Caroline Kennedy, Robert DeNiro". Bloomberg.

^ "Board of Trustees". WGBH. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

^ Cohan, William. "David Koch's Chilling Effect on Public Television". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

^ Cassidy, Chris (October 4, 2013). "Activists put heat on 'GBH to oust donor, board giant". Boston Herald. Archived from the original on December 8, 2014.

^ WGBH (10 October 2018). "Funders — NOVA". PBS. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.Funders for Season 44 include Draper, 23andMe, Cancer Treatment Centers of America, the David H. Koch Fund for Science, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and PBS Stations. ... Funders for Season 40 include Boeing (episodes 4007, 4009-4015, 4017-4024), Lockheed Martin (episodes 4003-4005) Franklin Templeton (episodes 4007, 4009-4016) the David H. Koch Fund for Science, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and PBS Stations.

^ "Smithsonian to Open Hall Dedicated to Story of Human Evolution". The Washington Post. March 30, 2010.

^ "IHO Research Council and Executive Board". Institute of Human Origins. Archived from the original on April 19, 2016.

^ "Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History to Build New Dinosaur Hall | Newsdesk". Newsdesk.si.edu. May 3, 2012. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

^ Trescott, Jacqueline (May 3, 2012). "David Koch donates $35 million to National Museum of Natural History for dinosaur hall". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

^ ab Cobbs, Lucy (February 25, 2010). "David Koch Named Lifetime Trustee". Deerfield Scroll.

^ Media (2015-02-02). "The Koch Brothers' Ten Most Shocking Power Grabs". Retrieved February 14, 2016.

^ "$3.1 Million Raised at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory's 2007 Double Helix Medals Dinner". November 21, 2007.

^ Nelson, Colleen Mccain; Fields, Gary (July 16, 2015). "Obama, Koch Brothers in Unlikely Alliance to Overhaul Criminal Justice". Wall Street Journal.

^ abc Horwitz, Sari (August 15, 2015). "Unlikely Allies". Washington Post.

^ Hudetz, Mary (October 15, 2015). "Forfeiture reform aligns likes of billionaire Charles Koch, ACLU". The Topeka Capital Journal.

^ "Koch brothers join Obama in advocating US prison reform". Russian Today. July 17, 2015.

^ Lewis, Matt (September 2, 2010). "Koch Brothers Donate to Charity as well as Right Wing Causes". Politics Daily. AOL News. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

^ Nick, Gillespie (2010-08-25). "The Official Koch Industries Reply to The New Yorker Hit Piece". reason.com. reason.com. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

^ Levine, Yasha (September 1, 2010). "7 Ways the Koch Bros. Benefit from Corporate Welfare". New York Observer. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

^ "George Mason University Board of Visitors: Kimberly Dennis". Retrieved December 30, 2014.

^ Dennis, Kimberly O. (November 15, 2010). "Democrats Can't Blame the Koch Brothers (However Much They Might Want To)". National Review Online. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

^ Ferguson, Andrew (April 21, 2011). "The 2011 TIME 100". TIME. Retrieved April 22, 2011.

^ ab Elizabeth Bumiller (January 11, 1998). "Woman Ascending A Marble Staircase". The New York Times. Retrieved August 31, 2010.

^ ab NYT staff (May 26, 1996). "Weddings: Julia M. Flesher, David H. Koch". Style. The New York Times. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

External links

Appearances on C-SPAN

Political contributions from Influence Explorer at the Sunlight Foundation

Names in the News: David and Charles Koch at FollowTheMoney.org

Collected news and commentary at The New York Times

Daniel Schulman (May 20, 2014). Sons of Wichita. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-1455518739.

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by David Bergland | Libertarian nominee for Vice President of the United States 1980 | Succeeded by Jim Lewis |