Common nighthawk

| Common nighthawk | |

|---|---|

| |

Conservation status | |

Least Concern (IUCN 3.1)[1] | |

Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Caprimulgiformes |

| Family: | Caprimulgidae |

| Genus: | Chordeiles |

| Species: | C. minor |

Binomial name | |

Chordeiles minor (J. R. Forster, 1771)[2] | |

| Subspecies | |

See text | |

| |

Synonyms | |

Caprimulgus minor | |

The common nighthawk (Chordeiles minor) is a medium-sized [3][4]crepuscular or nocturnal bird[3][5] within the nightjar family, whose presence and identity are best revealed by its vocalization. Typically dark[3] (grey, black and brown),[5] displaying cryptic colouration and intricate patterns, this bird is difficult to spot with the naked eye during the day. Once aerial, with its buoyant but erratic flight, this bird is most conspicuous. The most remarkable feature of this aerial insectivore is its small beak that belies the massiveness of its mouth. Some claim appearance similarities to owls. With its horizontal stance[3] and short legs, the common nighthawk does not travel frequently on the ground, instead preferring to perch horizontally, parallel to branches, on posts, on the ground or on a roof.[5] The males of this species may roost together but the bird is primarily solitary. The common nighthawk shows variability in territory size.[4]

This caprimulguid has a large, flattened head with large eyes; facially it lacks rictal bristles. The common nighthawk has long slender wings that at rest extend beyond a notched tail. There is noticeable barring on the sides and abdomen,[4] also white wing-patches.[3]

The common nighthawk measures 22 to 25 cm (8.7 to 9.8 in) long,[4] displays a wing span of 51 to 61 cm (20 to 24 in)[6] weighs 55 to 98 g (1.9 to 3.5 oz),[4][6] and has a life span of 4 to 5 years.[4]

Contents

1 Names and etymology

2 Taxonomy

2.1 Subspecies

2.2 History

2.3 Field identification

3 Habitat and distribution

3.1 Migration

4 Moult

5 Behavior

5.1 Vocalization

5.2 Feeding and diet

5.3 Drinking, pellet-casting and droppings

5.4 Reproduction and nesting

5.5 Incubation, hatching and young

5.6 Predators

6 Status and conservation

7 References

8 External links

Names and etymology

The genus name Chordeiles is from Ancient Greek khoreia, a dance with music, and deile, "evening". The specific minor is Latin for "smaller".[7]

The term "nighthawk", first recorded in the King James Version of 1611, was originally a local name in England for the European nightjar. Its use in the Americas to refers to members of the genus Chordeiles and related genera was first recorded in 1778.[8]

The common nighthawk is sometimes called a "bull-bat", due to its perceived "bat-like" flight, and the "bull-like" boom made by its wings as it pulls from a dive.[6]

They, in addition to other nightjars, are also sometimes called "bugeaters", for their insectivore diet. The common nighthawk is likely the source of Nebraska's state nickname, which was once the "Bugeater State", and its people were known as "bugeaters".[9][10][11] The Nebraska Cornhuskers college athletic teams were also briefly known the Bugeaters, before adopting their current name, which was also adopted by the state as a whole.

In flight showing characteristic white wing bars.

Taxonomy

Within the family Caprimulgidae, the subfamily Chordeilinae (nighthawks) are limited to the New World and are distinguished from the subfamily Caprimulginae, by the lack of rictal bristles.

The American Ornithologists' Union treated the smaller Antillean nighthawk as conspecific with the common nighthawk until 1982.[4]

Up until the early 19th century, the common nighthawk and the whip-poor-will were thought to be one species. The latter's call was explained as the nocturnal expression of the common nighthawk. Alexander Wilson, "The Father of American Ornithology", correctly made the differentiation between the two species.

Subspecies

There are 9 currently recognized subspecies:[12]

C. m. panamensis – Eisenmann, 1962: breeds on the Pacific slope of Panama and north west Costa Rica. It is noted to depart Panama during winter for points in South America

C. m. neotropicalis – Selander & Alvarez del Toro, 1955: breeds in south Mexico and Honduras

C. m. howelli – Oberholser, 1914: breeds in west central United States (north Texas, west Oklahoma, and Kansas to east Colorado, less typical form in central Colorado, north east Utah and Wyoming). It is darker than sennetti and paler and less cinnamon than henryi.

C. m. hesperis – Grinnell, 1905: breeds in south west Canada (British Columbia and Alberta), the western interior of United States (Washington, Montana, Nevada, interior California, Utah, extreme north Colorado, west Wyoming). It is darker than sennetti and paler and less cinnamon than henryi.

C. m. aserriensis – Cherrie, 1896: breeds from south central Texas to north Mexico. It is darker than sennetti and paler and less cinnamon than henryi.

C. m. chapmani – Coues, 1888: breeds from southeast Kansas to east North Carolina and southwards to south east Texas and south Florida. It is the darkest of the subspecies.

C. m. sennetti – Coues, 1888: breeds in the north Great Plains: east Montana, south Saskatchewan, Manitoba, southwards to North Dakota, Minnesota and Iowa. It is the palest of the subspecies.

C. m. henryi – Cassin, 1855: breeds from south east Utah and south west Colorado through mountains of west Texas, Arizona and New Mexico (less north east) to east Sonora, Chihuahua, and Durango. It is unique with ochraceous to deep cinnamon feather edges on upperparts.

C. m. minor – (J.R. Forster, 1771): breeds from south east Alaska to Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, and south Canada/northern United States (Minnesota, Indiana) to Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia and Oklahoma. Considered by some as the darkest subspecies.[13]

History

This species is recorded as widespread during the Late Pleistocene, from Virginia to California and from Wyoming to Texas.[4]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, because their name contained the word "hawk", they had habits of diurnal insect hunting, and they travelled in migrating flocks, they were hunted for sport and nourishment and because they were seen as predators.[6]

Field identification

Common nighthawk in British Columbia

The common nighthawk is distinguished from other caprimulguids by its forked tail (includes a white bar in males); its long, unbarred, pointed wings with distinctive white patches; its lack of rictal bristles, and the key identifier – their unmistakable calls.[13] These birds range from 21 to 25 cm (8.3 to 9.8 in) in total length and from 51 to 61 cm (20 to 24 in) in wingspan.[14] Body mass can vary from 55 to 98 g (1.9 to 3.5 oz). Among standard measurements, the wing chord is 17.2 to 21.3 cm (6.8 to 8.4 in), the tail is 13 to 15.1 cm (5.1 to 5.9 in), the bill is 0.5 to 0.8 cm (0.20 to 0.31 in) and the tarsus is 1.2 to 1.6 cm (0.47 to 0.63 in).

The common nighthawk resembles both the Antillean nighthawk and the lesser nighthawk and occurs at least seasonally in the entire North American range of both of these species. The lesser nighthawk is a smaller bird and displays more buffy on the undertail coverts, where the common nighthawk shows white. Common nighthawks and Antillean nighthawks exhibit entirely dark on the basal portion of the primary feathers, whereas lesser nighthawks have bands of buffy spots. Common and Antillean nighthawks have a longer outermost primary conveying a pointier wing tip than the lesser nighthawk. The common nighthawk forages higher above ground than the lesser nighthawk and has a different call. The only reliable way to distinguish Antillean nighthawk without disturbance is also by the differences in their calls. Visually, they may only be distinguished as different from the common nighthawk once in the hand. Subtle differences are reported to be a challenge in field identification.[4]

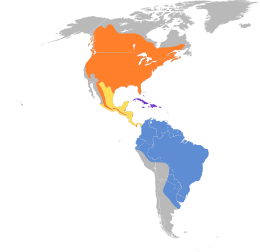

Habitat and distribution

The common nighthawk may be found in forests, desert, savannahs, beach and desert scrub, cities,[3] and prairies,[4] at elevations of sea level or below to 3,000 m (9,800 ft).[3] They are one of a handful of birds that are known to inhabit recently burned forests, and then dwindle in numbers as successional growth occurs over the succeeding years or decades. The common nighthawk is drawn into urban built-up areas by insects.[5]

The common nighthawk is the only nighthawk occurring over the majority of northern North America.

Food availability is likely a key factor in determining which and when areas are suitable for habitation. The common nighthawk is not well adapted to survive in poor conditions, specifically low food availability. Therefore, a constant food supply consistent with warmer temperatures is a driving force for migration and ultimately survival.

It is thought that the bird is not able to enter torpor,[4] although recent evidence suggests the opposite.[13]

Migration

During migration, common nighthawks may travel 2,500 to 6,800 kilometres (1,600 to 4,200 mi). They migrate by day or night in loose flocks; frequently numbering in the thousands,[6] no visible leader has been observed. The enormous distance travelled between breeding grounds and wintering range is one of the North America's longer migrations. The northbound journey commences at the end of February and the birds reach destinations as late as mid-June. The southbound migration commences mid-July and reaches a close in early October.[4]

Common nighthawk in flight, near Miami, Florida

While migrating, these birds have been reported travelling through middle America, Florida, the West Indies,[6] Cuba, the Caribbean and Bermuda,[4] finally completing their journey in the wintering grounds of South America,[6][13] primarily Argentina.[13]

As aerial insectivores, the migrants will feed en route,[6] congregating to hunt in marshes, rivers and on lakeshores. In Manitoba and Ontario, Canada, it is reported that during migration the nighthawks are seen most commonly in the late afternoon, into the evening,[4][5] with a burst of sunset feeding activities.[5]

Additionally, it has been noted that during migration the birds may fly closer to the ground than normal; possibly foraging for insects. There is speculation that feeding also occurs at higher altitudes.

The common nighthawk winters in southern South America, but distribution in this range is poorly known due to difficulties in distinguishing the bird from the lesser nighthawk and in differentiating between migrants and overwintering birds. In some South and Central American countries, a lack of study has led to restricted and incomplete records of the bird. Records do support wintering in Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Argentina.[4]

Moult

In the common nighthawk, all bodily plumage and rectrices are replaced in the post-juvenile moult. This moult commences in September at the breeding grounds; the majority of the body plumage is replaced but wing-coverts and rectrices are not completed until January–February, once the bird arrives at the wintering grounds. There is no other moult prior to the annual moult of the adult. Common nighthawk adults have a complete moult that occurs mostly or completely on wintering grounds and is not completed until January or February.[13]

Behavior

Vocalization

There are no differences between the calls and song of the common nighthawk. The most conspicuous vocalization is a nasal peent or beernt during even flight. Peak vocalizations are reported 30 to 45 minutes after sunset.

| Chordeiles minor call Call of the common nighthawk (Chordeiles minor) |

Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

A croaking auk auk auk is vocalized by males while in the presence of a female during courtship. Another courtship sound, thought to be made solely by the males, is the boom, created by air rushing through the primaries after a quick downward flex of the wings during a daytime dive.

In defense of their nests, the females make a rasping sound, and males clap their wings together.[15] Strongly territorial males will perform dives against fledglings, females and intruders such as humans or raccoons.[4]

Feeding and diet

Frequent flyers, the long-winged common nighthawk hunts on the wing[13] for extended periods at high altitudes or in open areas.[5] Crepuscular, flying insects are its preferred food source. The hunt ends as dusk becomes night, and resumes when night becomes dawn.[13] Nighttime feeding (in complete darkness) is rare,[4] even on evenings with a full moon.[13] The bird displays opportunistic feeding tendencies, although it may be able to fine-tune its meal choice in the moments before capture.

Vision is presumed to be the main detection sense; no evidence exists to support or refute the use of echolocation. The birds have been observed to converge on artificial light sources in an effort to forage for insects enticed by the light.[4] The average flight speed of common nighthawks is 23.4 km/h (14.5 mph).[16]

Drinking, pellet-casting and droppings

The common nighthawk was observed to drink on its winter range by flying extremely low over the surface of the water.[17]

No evidence suggests this bird casts pellets.

The common nighthawk is recognized to discharge feces around nest and roosting positions. The bird will sporadically defecate in flight. The defecation is pungent.[4]

Reproduction and nesting

The common nighthawk breeds during the period of mid-March to early October.[6] It most commonly has only one brood per season, however sometimes a second brood is produced. The bird is assumed to breed every year. Reuse of nests by females in subsequent years has been reported.[4] A monogamous pattern has also recently been confirmed.[13]

Courting and mate selection occur partially in flight. The male dives and booms (see Vocalization) in an effort to garner female attention;[4][5] the female may be in flight herself or stationary on the ground.

Copulation occurs when the pair settles on the ground together; the male with his rocking body, widespread tail wagging and bulging throat expresses guttural croaking sounds. This display by the male is performed repeatedly until copulation.[4]

The preferred breeding/nesting habitat is in forested regions with expansive rocky outcrops, in clearings, in burned areas[5] or in small patches of sandy gravel.[4] The eggs are not laid in a nest, but on bare rock, gravel,[5] or sometimes a living substrate such as lichen.[4] Least popular are breeding sites in agricultural settings.[18] As displayed in the latter portion of the 20th century, urban breeding is in decline.[5] If urban breeding sites do occur, they are observed on flat gravel rooftops.

It is a solitary nester, putting great distances between itself and other pairs of the same species, but a nest would more commonly occur in closer proximity to other species of birds.

Females choose the nest site and are the primary incubators of the eggs; males will incubate occasionally. Incubation time varies but is approximately 18 days. The female will leave the nest unattended during the evening in order to feed. The male will roost in a neighbouring tree (the spot he chooses changes daily); he guards the nest by diving, hissing, wing-beating or booming at the sites. In the face of predation, common nighthawks do not abandon the nest easily; instead they likely rely on their cryptic colouration to camouflage themselves. If a departure does occur, the females have been noted to fly away, hissing at the intruder[4] or performing a disturbance display.[13]

Incubation, hatching and young

The eggs are elliptical, strong, and variably coloured with heavy speckling. The common nighthawk lays two 6–7 g (0.21–0.25 oz) eggs per clutch; the eggs are laid over a period of 1 to 2 days. The female alone displays a brood patch.

The chicks may be heard peeping in the hours before they hatch. Once the chicks have broken out of the shells, the removal of the debris is necessary in order to avoid predators. The mother may carry the eggshells to another location or consume a portion of them. Once hatched, the nestlings are active and have their eyes fully or half open; additionally they display a sparing cover of soft down feathers. The chicks are semiprecocial. By day 2, the hatchlings' bodily mass will double and they will be able to self-propel towards their mother's call. The young will hiss at an intruder.

The young are fed by regurgitation before sunrise and after sunset. The male parent assists in feeding fledglings and will also feed the female during nesting. No records exist to support a parent's ability to physically carry a chick.

On their 18th day, the young will make their first flight; by days 25–30, they are flying proficiently. The young are last seen with their parents on day 30. Complete development is shown between their 45–50th day. At day 52, the juvenile will join the flock, potentially migrating. Juvenile birds, in both sexes, are lighter in colour and have a smaller white wing-patch than adult common nighthawks.[4]

Predators

Like other members of the caprimulgid clan, the nighthawk's ground nesting habits endanger eggs and nestlings to predation by ground carnivores, such as skunks, raccoons and opossums.[19] Confirmed predation on adults is restricted to domestic cats, golden eagles and great horned owls.[20]Peregrine falcons have also been confirmed to attack nighthawks as prey, although the one recorded predation attempt was unsuccessful.[21] Other suspected predators are likely to attack them, such as dogs, coyotes, foxes, hawks, American kestrels,[22]owls, crows and ravens and snakes.[23]

Status and conservation

There has been a general decline in the number of common nighthawks in North America, but some population increases also have occurred[4] in other geographical locations.[13] The bird's large range makes individual risk thresholds in specific regions difficult to establish.[1] In Ontario, the common nighthawk is rated as a species of special concern.[24]

The Common nighthawk's trait of being a ground-nesting bird makes it particularly susceptible to predators, some of which include domestic cats, ravens, snakes, dogs, coyotes, falcons and owls.

Lack of flat roofs, pesticides,[4] increased predation and loss of habitat[13] are noted factors of their decline. Further unstudied potential causes of decline include climate change, disease, road kills, man-made towers (posing aerial hazards) and parasites.[4]

The absence of flat roofs (made with gravel) in urban settings is an important cause of decline. In an effort to provide managed breeding areas, gravel pads have been added in the corners of rubberized roofs; this proves acceptable, as nesting has been observed.[13]

References

^ ab BirdLife International (2012). "Chordeiles minor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ "Chordeiles minor". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

^ abcdefg Sibley, David Allen (2001). The Sibley Guide to Bird Life & Behaviour. Chanticleer Press, Inc.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaabac Poulin, R.; Grindal, S.; Brigham, R. (1996). Common Nighthawk. No. 213. The Birds of North America. The American Ornithologists' Union.

^ abcdefghijk The Birds of Manitoba. Manitoba Avian Research Committee, Manitoba Naturalists Society. 2003. ISBN 9780969728016.

^ abcdefghi Elphick, J., ed. (2007). Atlas of Bird Migration. Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1554079711.

^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 104, 256. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

^ "Nighthawk". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

^ http://www.netstate.com/states/intro/ne_intro.htm

^ Nancy Capace, Encyclopedia of Nebraska. Somerset Publishers, Inc., Jan 1, 1999, p2-3

^ U. S. An Index to the United States of America: Historical, Geographical and Political. A Handbook of Reference Combining the "curious" in U. S. History. Boston, MA: D. Lothrop Company. 1890. p. 77.

^ Gill, F.; Donsker, D., eds. (2014). "IOC World Bird List (v 4.4)". doi:10.14344/IOC.ML.4.4. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

^ abcdefghijklmn Holyoak, D.T. (2001). Nightjars and their Allies: the Caprimulgiformes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854987-3.

^ "Common Nighthawk". mountainnature.com. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

^ http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Common_Nighthawk/sounds

^ Brigham, R.M.; Fenton, M.B.; Aldridge, H.D.J.N. (1998). "Flight Speed of Foraging Common Nighthawks (Chordeiles minor): Does the Measurement Technique Matter?". American Midland Naturalist. 139 (2): 325–330. doi:10.1674/0003-0031(1998)139[0325:fsofcn]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 2426689.

^ Canevari, M.; Canevari, P.; Carrizo, G.; Harris, G.; Mata, J.; Straneck, R. (1991). Nueva guia de las aves Argentinas [New Guide to the Birds of Argentina] (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Fundacion Acindar. cited in Poulin, R.; Grindal, S.; Brigham, R. (1996). Common Nighthawk. No. 213. The Birds of North America. The American Ornithologists' Union.

^ Gillette, L. (1991). "Survey of Common Nighthawks in Minnesota, 1990". The Loon. 62: 141–143. cited in The Birds of Manitoba. Manitoba Avian Research Committee, Manitoba Naturalists Society. 2003. p. 238. ISBN 9780969728016.

^ Kantrud, H.A.; Higgins, K.F. (1992). "Nest and nest site characteristics of some groundnesting, nonpasserine birds of northern grasslands". Prairie Naturalist. 24: 67–84.

^ Olendorff, R.R. (1976). "The food habits of North American golden eagles". American Midland Naturalist. 95 (1): 231–236. doi:10.2307/2424254. JSTOR 2424254.

^ Bennett, G. (1987). "A vellication of nighthawks". Birdfinding in Canada. 7: 16.

^ Gross, A.O. (1940). Bent, A.C., ed. "Eastern Nighthawk - Life histories of North American cuckoos, goatsuckers, hummingbirds, and their allies". U.S. Natl. Mus. Bull. 176: 206–234.

^ Marzilli, V. (1989). "Up on the roof". Maine Fish and Wildlife. 31: 25–29.

^ "Common nighthawk". Government of Ontario. September 10, 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chordeiles minor. |

Wikispecies has information related to Chordeiles minor |

- BirdLife species factsheet for Chordeiles minor

"Chordeiles minor". Avibase.

"Common nighthawk media". Internet Bird Collection.

Common nighthawk photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

Interactive range map of Chordeiles minor at IUCN Red List maps

Common nighthawk Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Audio recordings of Common nighthawk on Xeno-canto.