Pelvic fin

Pelvic fins from Barbonymus gonionotus.

Pelvic fins are paired fins located on the ventral surface of fish. The paired pelvic fins are homologous to the hindlimbs of tetrapods.[1]

Contents

1 Structure and function

1.1 Structure

1.2 Function

2 Development

3 References

Structure and function

Structure

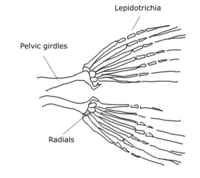

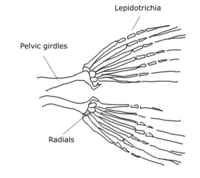

In actinopterygians, the pelvic fin consists of two endochondrally-derived bony girdles attached to bony radials. Dermal fin rays (lepidotrichia) are positioned distally from the radials. There are three pairs of muscles each on the dorsal and ventral side of the pelvic fin girdle that abduct and adduct the fin from the body.

Pelvic fin structures can be extremely specialized in actinopterygians. Gobiids and lumpsuckers modify their pelvic fins into a sucker disk that allow them to adhere to the substrate or climb structures, such as waterfalls[2]. In priapiumfish, males have modified their pelvic structures into a spiny copulatory device that grasps the female during mating[3].

Pelvic fin skeleton for Danio rerio, zebrafish.

Gobiids have modified their pelvic fins into adhesive suckers.

Lumpsuckers use their modified pelvic fins to adhere to the substrate.

Function

In actinopterygian steady state swimming, the pelvic fins are actively controlled and used to provide powered corrective forces[4][5]. Careful timing of the pelvic fin movement during whole-body movements allows the pelvic fins to generate forces that dampen the forces from the entire body, therefore stabilizing the fish. For maneuvers, electromyogram data shows that pelvic fin muscles are activated after the start of the maneuver, indicating that the fins are used more for stabilization instead of generating the maneuver[4].

In rays and skates, pelvic fins can be used for "punting," where they asynchronously or synchronously push off the substrate to propel the animal forwards[6].

Development

Unlike limb development in tetrapods, where the forelimb and hindlimb buds emerge at roughly the same timepoint, the pelvic fin bud emerges much later than the pectoral fin[7]. While the pectoral fin bud is apparent at 36 hours post fertilization (hpf) in zebrafish, the pelvic fin bud is only clear at around 21 days post fertilization (dpf), roughly when the animal is 8 mm in length.

The pelvic fin appears at roughly 21 days post fertilization in zebrafish

In zebrafish, the pelvic fin bud starts as a mesenchymal condensation that forms an apical ectodermal thickening[7]. A fin fold forms from this thickening, which is then invaded by migratory mesenchyme, separating the fin bud into the proximal mesenchyme (which will give rise to the endoskeletal girdle and radials) and the distal mesenchyme (which will give rise to dermal fin rays).[7]

References

^ Hall, Brian K. (2008-09-15). Fins into Limbs: Evolution, Development, and Transformation. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226313405..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Maie, Takashi; Schoenfuss, Heiko L.; Blob, Richard W. (2007-09-10). "Ontogenetic Scaling of Body Proportions In Waterfall-climbing Gobiid Fishes from Hawai'i and Dominica: Implications for Locomotor Function". Copeia. 2007 (3): 755–764. doi:10.1643/0045-8511(2007)2007[755:OSOBPI]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0045-8511.

^ Shibukawa, Koichi, Dinh Dac Tran, and Loi Xuan Tran. "Phallostethus cuulong, a new species of priapiumfish (Actinopterygii: Atheriniformes: Phallostethidae) from the Vietnamese Mekong." Zootaxa 3363.1 (2012): 45-51.

^ ab Standen, E. M. (2008-09-15). "Pelvic fin locomotor function in fishes: three-dimensional kinematics in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)". Journal of Experimental Biology. 211 (18): 2931–2942. doi:10.1242/jeb.018572. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 18775930.

^ Standen, E. M. (2010-03-01). "Muscle activity and hydrodynamic function of pelvic fins in trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)". Journal of Experimental Biology. 213 (5): 831–841. doi:10.1242/jeb.033084. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 20154199.

^ Macesic, Laura J.; Kajiura, Stephen M. (2010-10-01). "Comparative punting kinematics and pelvic fin musculature of benthic batoids". Journal of Morphology. 271 (10): 1219–1228. doi:10.1002/jmor.10865. ISSN 1097-4687. PMID 20623523.

^ abc Grandel, Heiner; Schulte-Merker, Stefan (1998-12-01). "The development of the paired fins in the Zebrafish (Danio rerio)". Mechanisms of Development. 79 (1–2): 99–120. doi:10.1016/S0925-4773(98)00176-2. ISSN 0925-4773.