Brownie (folklore)

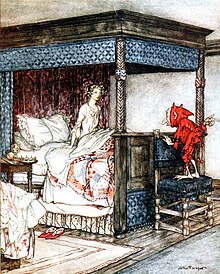

Illustration of a brownie sweeping with a handmade broom by Arthur Rackham | |

| Grouping | Legendary creature |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Fairy Goblin Household spirit |

| Other name(s) | Brounie Urisk Brùnaidh Ùruisg Gruagach |

| Country | Scotland and Northern England |

| Habitat | Within the home |

A brownie or broonie (Scots),[1] also known as a brùnaidh or gruagach (Scottish Gaelic), is a household spirit from British folklore that is said to come out at night while the owners of the house are asleep and perform various chores and farming tasks. The human owners of the house must leave a bowl of milk or cream or some other offering for the brownie, usually by the hearth. Brownies are described as easily offended and will leave their homes forever if they feel they have been insulted or in any way taken advantage of. Brownies are characteristically mischievous and are often said to punish or pull pranks on lazy servants. If angered, they are sometimes said to turn malicious, like boggarts.

Brownies originated as domestic tutelary spirits, very similar to the Lares of ancient Roman tradition. Descriptions of brownies vary regionally, but they are usually described as ugly, brown-skinned, and covered in hair. In the oldest stories, they are usually human-sized or larger. In more recent times, they have come to be seen as small and wizened. They are often capable of turning invisible and they sometimes appear in the shapes of animals. They are always either naked or dressed in rags. If a person attempts to present a brownie with clothing or if a person attempts to baptize him, he will leave forever.

Although the name brownie originated as a dialectal word used only in northern England and Scotland, it has since become the standard term for all such creatures throughout Great Britain. Regional variants in England and Scotland include hobs, silkies, and ùruisgs. Variants outside England and Scotland are the Welsh Bwbach and the Manx Fenodyree. Brownies have also appeared outside of folklore, including in John Milton's poem L'Allegro. They became popular in works of children's literature in the late nineteenth century and continue to appear in works of modern fantasy. The Brownies in the Girl Guides are named after a short story by Juliana Horatia Ewing based on brownie folklore.

Contents

1 Origin

2 Traditions

2.1 Activities

2.2 Appearance

2.3 Leaving the house

2.4 Gifts of clothing

2.5 Brownie sway

3 Regional variants

3.1 Bwbach

3.2 Fenodyree

3.3 Hobs and hearth spirits

3.4 Silkie

3.5 Ùruisg

3.6 Other variants

4 Analysis

4.1 Classification

4.2 Functionalist analysis

5 Outside of folklore

5.1 Early literary appearances

5.2 Mass marketing

5.3 Modern fantasy

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

8.1 Bibliography

Origin

Roman Lararium, or household shrine to the Lares, from the House of the Vettii in Pompeii. Brownies bear many similarities to the Roman Lares.[2][3][4]

Brownies originated as domestic tutelary spirits, very similar to the Lares of ancient Roman tradition, who were envisioned as the protective spirits of deceased ancestors.[2][3][4][5] Brownies and Lares are both regarded as solitary and devoted to serving the members of the house.[6] Both are said to be hairy and dress in rags[6] and both are said to demand offerings of food or dairy.[6] Like Lares, brownies were associated with the dead[7][6] and a brownie is sometimes described as the ghost of a deceased servant who once worked in the home.[6] The Cauld Lad of Hilton, for instance, was reputed to be the ghost of a stable boy who was murdered by one of the Lords of Hilton Castle in a fit of passion.[8] Those who saw him described him as a naked boy.[9] He was said to clean up anything that was untidy and make messes of things that were tidy.[9]

The family cult of deceased ancestors in ancient times centred around the hearth,[2] which later became the place where offerings would be left for the brownie.[3] The most significant difference between brownies and Lares is that, while Lares were permanently bound to the house in which they lived,[3][6] brownies are seen as more mobile, capable of leaving or moving to another house if they became dissatisfied.[3][6] One story describes a brownie who left the house after the stingy housewife fired all the servants because the brownie was doing all the work and refused to return until all the servants had been re-hired.[3]

Traditions

Activities

Traditions about brownies are generally similar across different parts of Great Britain.[10] They are said to inhabit homes and farms.[10][11] They only work at night, performing necessary housework and farm tasks while the human residents of the home are asleep.[6][10][11] The presence of the brownie is believed to ensure household prosperity[10][11] and the human residents of the home are expected to leave offerings for the brownie, such as a bowl of cream or porridge, or a small cake.[6][10][11] These are usually left on the hearth.[10] The brownie will punish household servants who are lazy or slovenly by pinching them while they sleep, breaking or upsetting objects around them, or causing other mischief.[5][6][10] Sometimes they are said to create noise at night or leave messes simply for their own amusement.[10] In some early stories, brownies are described as guarding treasure, a non-domestic task outside of their usual repertoire.[3]

Brownies are almost always described as solitary creatures who work alone and avoid being seen.[10][12][13] There is rarely said to be more than one brownie living in the same house.[10][14][a] Usually, the brownie associated with a house is said to live in a specific place, such as a particular nearby cave, stream, rock, or pond.[16] Some individual brownies are occasionally given names.[10] Around 1650, a brownie at Overthwaite in Westmorland was known as "Tawny Boy"[10] and a brownie from Hilton in County Durham was known as "Cauld Lad".[10] Brownies are said to be motivated by "personal friendships and fancies" and may sometimes be moved to perform extra work outside of their normal duties, such as, in one story of a brownie from Balquam, fetching a midwife when the lady of the house went into labour.[17]

In 1703, John Brand wrote in his description of Shetland that:

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

Not above forty or fifty years ago, every family had a brownie, or evil spirit, so called, which served them, to which they gave a sacrifice for his service; as when they churned their milk, they took a part thereof, and sprinkled every corner of the house with it, for Brownie’s use; likewise, when they brewed, they had a stone which they called "Brownie’s stane", wherein there was a little hole into which they poured some wort for a sacrifice to Brownie. They also had some stacks of corn, which they called Brownie's Stacks, which, though they were not bound with straw ropes, or in any way fenced as other stacks used to be, yet the greatest storm of wind was not able to blow away straw off them.

Appearance

Brownies are virtually always male,[11] but female brownies, such as Meg Mullach (or "Hairy Meg"), have occasionally been described as well.[18][19] They are usually envisioned as ugly[12][16][20] and their appearances are sometimes described as frightening or unsettling to members of the houses in which they reside.[12] They received their name from the fact that they are usually described as brown-skinned and completely covered in hair.[12] In the earliest traditions, brownies are either the same size as humans or sometimes larger,[16] but, in later accounts, they are described as "small, wizened, and shaggy".[16] They are often characterized as short and rotund,[11][21] a description that may be related to mid-seventeenth-century Scottish descriptions of the Devil.[21] Two Scottish witchcraft confessions, one by Thomas Shanks in 1649 and another by Margaret Comb in 1680, both describe meetings with a "thick little man".[21] The man in these descriptions may have been conceived as a brownie.[21]

In the late nineteenth century, the Irish folklorist Thomas Keightley described the brownie as "a personage of small stature, wrinkled visage, covered with short curly brown hair, and wearing a brown mantle and hood".[22] Brownies are usually described as either naked or clothed in rags.[11][12][23] Brownies of the Scottish Lowlands were said not to have noses, but instead had merely a single hole in the centre of their face.[12][16] In Aberdeenshire, brownies are sometimes described as having no fingers or toes.[16] Sometimes brownies are stated to appear like children, either naked or dressed in white tunics.[16]

Like the Phooka in Irish folklore, brownies are sometimes described as taking the forms of animals.[16] As a rule, they can turn invisible,[16] but they are supposed to rarely need this ability because they are already experts at sneaking and hiding.[16] A story from Peeblesshire tells of two maids who stole a bowl of milk and a bannock that had been left out for the brownie.[24] They sat down together to eat them, but the brownie sat between them invisibly and whenever either of them tried to eat the bannock or drink the milk, the brownie would steal it from them.[24] The two maids began arguing, each accusing the other of stealing her milk and bannock.[24] Finally, the brownie laughed and cried out: "Ha, ha, ha! Brownie has't a'!"[25][26]

Leaving the house

If the brownie feels he has been slighted or taken advantage of, he will vanish forever, taking the prosperity of the house with him.[12][10][27] Sometimes the brownie is said to fly into a rage and wreck all his work before leaving.[12] In extreme cases, brownies are even sometimes said to turn into malicious boggarts if angered or treated improperly.[10] A brownie is said to take offence if a human observes him working, if a human criticizes him, or if a human laughs at him.[10][27] Brownies are supposedly especially angered by anything they regard as contempt or condescension.[12][27] The brownie at Cranshaws in Berwickshire is said to have mown and thrashed the grain for years.[24] Then someone commented that the grain had been poorly mown and stacked,[24] so, that night, the brownie carried all the grain to Raven Crag two miles away and hurled it off the cliff, all the while muttering:[24]

It's no' weel mow'd! It's no' weel mow'd!—

Then it's ne'er be mow'd by me again;

I'll scatter it owre the Raven Stane

And they'll hae some wark ere it's mow'd again![24]

A brownie can also be driven away if someone attempts to baptize him.[27] In some stories, even the manner in which their bowls of cream are given is enough to drive the brownie away.[28] The brownie of Bodsbeck, near the town of Moffat in Scotland, left for the nearby farm of Leithenhall after the owner of Bodsbeck called for him after pouring his cream, instead of letting him find the cream himself.[28]

Sometimes giving the brownie a name was enough to drive him away.[14] A brownie who haunted Almor Burn near Pitlochry in Perthshire was often heard splashing and paddling in the water.[14] He was said to go up to the nearby farm every night with wet feet and, if anything was untidy, he would put it in order, but, if anything was tidy, he would hurl it around and make a mess.[14] The people of the area feared him and did not go near the road leading up from the water at night.[14] A man returning from the market one night heard him splashing in the water and called out to him, addressing him by the nickname "Puddlefoot".[14] Puddlefoot exclaimed in horror, "I've gotten a name! 'Tis Puddlefoot they call me!"[14] Then he vanished forever and was never heard again.[14]

Gifts of clothing

A recurring folkloric motif holds that, if presented with clothing, a brownie will leave his family forever and never work for them again,[12][29][30] similar to the Wichtelmänner in the German story of "The Elves and the Shoemaker".

If the family the brownie works for gives him a gift of clothing, he will leave forever and refuse to work for the family.[6][12][29][30] The first mention in English of a brownie disappearing after being presented with clothes comes from Book Four, Chapter Ten of Reginald Scot's The Discoverie of Witchcraft, published in 1584.[29] Sometimes brownies are reported to recite couplets before disappearing.[31] One brownie from Scotland is said to have angrily declared:

Red breeks and a ruffled sark!

Ye'll no get me to do your wark![12][27]

Another brownie from Berwickshire is said to have declared:

Gie Brownie a coat, gie Brownie a sark,

Ye'se get nae mair o' Brownie's wark.[32]

Explanations differ regarding why brownies disappear when presented with clothes,[33] but the most common explanation is that the brownie regards the gift of clothing as an insult.[6][12][34] One story from Lincolnshire, first recorded in 1891, attempts to rationalize the motif by making a brownie who is accustomed to being presented with linen shirts become enraged upon being presented with a shirt made of sackcloth.[33][35] The brownie in the story sings before disappearing:

Harden, harden, harden hamp,

I will neither grind nor stamp;

Had you given me linen gear,

I have served you many a year.

Thrift may go, bad luck may stay,

I shall travel far away.[33][35]

The Cauld Lad of Hilton seems to have wanted clothes and to have been grateful for the gift of them, yet still refused to stay after receiving them.[9][33] At night, people were supposed to have heard him working and somberly singing:[9]

Wae's me! Wae's me!

The acorn is not yet

Fallen from the tree,

That's to grow to the wood,

That's to make the cradle,

That's to rock the bairn,

That's to grow a man,

That's to lay to me.[9]

After the servants presented him with a green mantle and hood, he is supposed to have joyfully sung before disappearing:[9][33]

Here's a cloak, and here's a hood!

The Cauld Lad of Hilton will do no more good![9][33]

It is possible that the Cauld Lad may have simply thought himself "too grand for work", a motif attested to in other folk tales,[33] or that the gift of clothing may have been seen as a means of freeing him from a curse.[9] A brownie from Jedburgh is also said to have desired clothing.[9] The servants are reported to have heard him one night saying, "Wae's me for a green sark!"[9] The laird ordered for a green shirt to be made for the brownie.[9] It was left out for him and he disappeared forever.[9] People assumed he had gone to Fairyland.[9]

Brownie sway

In the nineteenth century, the pothook used to hang pots over the fire was made with a crook in it, which was known in Herefordshire as the "brownie's seat" or "brownie's sway".[36] If the hook did not have crook on it, people would hang a horseshoe on it upside-down so the brownie would have a place to sit.[36] The brownie at the Portway Inn in Staunton on Wye reportedly had a habit of stealing the family keys[36] and the only way to retrieve them was for the whole family sit around the hearth and to set a piece of cake on the hob as an offering to the brownie.[37] Then they would all sit with their eyes closed, absolutely silent, and the missing keys would be hurled at them from behind.[37]

Regional variants

Although the name brownie originated in the early sixteenth century as a dialect word used only in the Scottish Lowlands and along the English border,[38] it has become the standard name for a variety of similar creatures appearing in the folklores of various cultures across Britain.[38] Stories about brownies are generally more common in England and the Lowlands of Scotland than in Celtic areas.[15] Nonetheless, stories of Celtic brownies are recorded.[39]

Bwbach

The Welsh name for a brownie is Bwbach.[32][40] Like brownies, Bwbachs are said to have violent tempers if angered.[32] The twelfth-century Welsh historian Gerald of Wales records how a Bwbach inflicted havoc and mischief upon a certain household that had angered him.[32] The nineteenth-century folklorist Wirt Sikes describes the Bwbach as a "good-natured goblin" who performs chores for Welsh maids.[40] He states that, right before she goes to bed, the maid must sweep the kitchen and make a fire in the fireplace and set a churn filled with cream by the fire with a fresh bowl of cream next to it.[40] The next morning, "if she is in luck", she will find the bowl of cream had been drunk and the cream in the churn has been dashed.[40] Sikes goes on to explain that, in addition to being a household spirit, the Bwbach is also the name for a terrifying phantom believed to sweep people away on gusts of air.[41] The Bwbach is said to do this on the behalf of spirits of the restless dead, who cannot sleep because of the presence of hidden treasure.[35] When these spirits fail to succeed in persuading a living mortal to remove the treasure, they have the Bwbach whisk the person away instead.[35] Briggs notes that this other aspect of the Bwbach's activities make it much more closely resemble the Irish Phooka.[35]

John Rhys, a Welsh scholar of Celtic culture and folklore, records a story from Monmouthshire in his 1901 book Celtic Folklore about a young maid suspected of having fairy blood, who left a bowl of cream at the bottom of the stairs every night for a Bwbach.[42] One night, as a prank, she filled the bowl with stale urine.[42] The Bwbach attacked her, but she screamed and the Bwbach was forced to flee to the neighboring farm of Hafod y Ynys.[42] A girl there fed him well and he did her spinning for her,[42] but she wanted to know his name, which he refused to tell.[42] Then, one day when she pretended to be out, she heard him singing his name, Gwarwyn-a-throt,[43] so he left and went to another farm, where he became close friends with the manservant, whose name was Moses.[43] After Moses was killed in the Battle of Bosworth Field, Gwarwyn-a-throt began behaving like a boggart, wreaking havoc across the whole town.[40] An old wise man, however, managed to summon him and banish him to the Red Sea.[40] Elements of this story recur throughout other brownie stories.[40]

Fenodyree

The Manx name for a brownie is Fenodyree.[35] The Fenodyree is envisioned as a "hairy spirit of great strength", who is capable of threshing an entire barn full of corn in a single night.[35] The Fenodyree is regarded as generally unintelligent.[35] One Manx folktale tells of how the Fenodyree once tried to round up a flock of sheep and had more trouble with a small, hornless, grey one than any of the others;[35] the "sheep" he had so much difficulty with turned out to be a hare.[35] The exact same mistake is also attributed to a brownie from Lancashire[35] and the story is also told in western North America.[26] Like other brownies, the Fenodyree is believed to leave forever if he is presented with clothing.[35] In one story, a farmer of Ballochrink gave the Fenodyree a gift of clothes in gratitude for all his work.[35] The Fenodyree was offended and lifted up each item of clothing, reciting the various illnesses each one would bring him.[35] The Fenodyree then left to hide away in Glen Rushen alone.[35]

Hobs and hearth spirits

Especially in Yorkshire and Lancashire, brownies are known as "Hobs" due to their association with the hearth.[44] Like brownies, Hobs would leave forever if presented with clothing.[44] A Hob in Runswick Bay in North Yorkshire was said to live in a natural cave known as the "Hob-Hole", where parents would bring their children for the Hob to cure them of whooping cough.[44] The Holman Clavel Inn in Somerset is also said to be inhabited by a mischievous Hob named Charlie.[45] The story was recorded by the folklorist R. L. Tongue in 1964 immediately after he heard it from a woman who lived next door to the inn.[45] Everyone in the locality knew about Charlie[45] and he was believed to sit on the beam of holly wood over the fire, which was known as the "clavvy" or "clavey".[45] Once, when the woman was having dinner with a local farmer, the servants set the table at the inn with "silver and linen",[45] but, as soon as they left the room and came back, Charlie had put all the table settings back where they had come from because he did not like the farmer she was meeting with.[45]

Hobs are sometimes also known as "Lobs".[46] Lob-Lie-by-the-Fire is the name of a large brownie who was said to perform farm labour.[46] In Scotland, a similar hearth spirit was known as the Wag-at-the-Wa.[36][47] The Wag-at-the-Wa was believed to sit on the pothook[36] and it was believed that swinging the pothook served as an invitation for him to come visit.[36] He was believed to pester idle servants, but he was said to enjoy the company of children.[36] He is described as a hideous, short-legged old man with a long tail who always dressed in a red coat and blue breeches with an old nightcap atop his head and a bandage around his face, since he was constantly plagued by toothache.[36] He also sometimes wore a grey cloak. He was often reported to laugh alongside the rest of the family if they were laughing,[36] but he was strongly opposed to the family drinking any beverages with more alcohol content than home-brewed ale.[36] He is said to have fled before the sign of the cross.[36]

Silkie

A female spirit known as the Silkie, who received her name from the fact that she was always dressed in grey silk, appears in English and Scottish folklore.[15][48] Like a ghost, the Silkie is associated with the house rather than the family who lives there,[15] but, like a brownie, she is said to perform chores for the family.[15][48][47] A famous Silkie was reported to haunt Denton Hall in Northumberland.[15] Briggs gives the report of a woman named Marjory Sowerby, who, as a little girl, had spoken with the last remaining Hoyles of Denten Hall, two old ladies, about the Silkie and its kindness to them.[15] They told her that the Silkie would clean the hearth and kindle fires for them.[15] They also mentioned "something about bunches of flowers left on the staircase".[15] Sowerby left the area in around 1902 and, when she returned over half a century later after World War II, the Hoyles were both long dead and the house was owned by a man who did not believe in fairies.[15] The stories about the Silkie were no longer told and instead the house was reputed to be haunted by a vicious poltergeist, who made banging noise and other strange noises and pulled pranks on the man.[15] The man eventually moved out.[15] Briggs calls this an example of a brownie turning into a boggart.[15]

Silkies were also sometimes believed to appear suddenly on roads at night to lonely travellers and frighten them.[47] Another Silkie is said to haunt the grounds of Fardel Hall in Devonshire.[49] This one is said to manifest in the form of a "beautiful young woman with long, golden hair, wearing a long silken gown" and supposedly guards a hoard of treasure buried on the grounds.[49] Few people have seen the spirit, but many claim to have heard the rustling of her silk dress.[49] She is believed to quietly strangle anyone who comes near finding the treasure.[49]

Ùruisg

The folklorist John Gregorson Campbell distinguishes between the English brownie, which lived in houses, and the Scottish ùruisg or urisk, which lived outside in streams and waterfalls and was less likely to offer domestic help.[50] Although brownies and ùruisgs are very similar in character, they have different origins.[51] Ùruisgs are sometimes described as half-man and half-goat.[52][53] They are said to have "long hair, long teeth, and long claws".[53] According to M. L. West, they may be Celtic survivals of goat-like nature spirits from Proto-Indo-European mythology, analogous to the Roman fauns and Greek satyrs.[54] Passersby often reported seeing an ùruisg sitting atop a rock at dusk, watching them go by.[53] During the summer, the ùruisg was supposed to remain in the solitude of the wilderness,[53] but, during the winter, he would come down and visit the local farms at night or take up residence in a local mill.[53]

Wild ùruisgs were troublemakers and vandals who perpetrated acts of butchery, arson, and ravaging,[55] but, once domesticated, they were fiercely loyal.[55] Wealthy and prominent families were said to have ùruisgs as household servants.[55] One chieftain of the MacFarlane clan was said to have been nursed and raised by the wife of an ùruisg.[55] The Graham clan of Angus told stories of an ùruisg that had once worked for one of their ancestors as a drudge.[55] The Maclachlan clan in Strathlachlan had an ùruisg servant named "Harry", possibly shortened from "the hairy one".[55] The MacNeils of Taynish and the Frazers of Abertarff also claimed to have ùruisg servants.[55] Ùruisgs were also known as ciuthachs or kewachs.[51] A story on the island of Eigg told of a ciuthach that lived in a cave.[51] In some parts of Scotland, similar domestic spirits were called Shellycoats, a name whose origin is uncertain.[22]

Other variants

"O Waken, Waken, Burd Isbel", illustration by Arthur Rackham to Young Bekie, showing Billy Blind waking Burd Isobel

A figure named "Billy Blind" or "Billy Blin", who bears close resemblances to both the brownie and the Irish banshee, appears in ballads of the Anglo-Scottish border.[56][57][58] Unlike brownies, who usually provide practical domestic aid, Billy Blind usually only provides advice.[57] He appears in the ballad of "Young Bekie", in which he warns Burd Isbel, the woman Bekie is pledged to marry, that Bekie is about to marry another woman.[59] He also appears in the ballad of "Willie's Lady" in which he also provides advice, but offers no practical aid.[57]

Briggs notes stories of other household spirits from British folklore who are reputed to haunt specific locations.[44] The "cellar ghost" is a spirit who guards wine in cellars from would-be thieves;[44] Lazy Lawrence is said to be protect orchards;[44]Awd Goggie scares children away from eating unripe gooseberries;[44] and Melch Dick guards nut thickets.[44] The Kilmoulis is a brownie-like creature from the Scottish Lowlands that is often said to inhabit mills.[16] He is said to have no mouth, but an enormous nose that covers most of his face.[16] He is fond of pranks and only the miller himself is able to control him.[16]

Analysis

Classification

Brownies have traditionally been regarded as distinct and different from fairies.[38] In 1777, a vicar of Beetham wrote in his notes on local folklore, "A Browny is not a fairey, but a tawny color'd Being which will do a great deal of work for a Family, if used well."[38] The writer Walter Scott agreed in his Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, in which he states, "The Brownie formed a class of beings distinct in habit and disposition from the freakish and mischievous elves."[38] Modern scholars, however, categorize brownies as household spirits, which is usually treated as a subcategorization of fairy.[60] Brownies and other household spirits differ significantly from other fairies in folklore, however.[10] Brownies are usually said to dwell alongside humans in houses, barns, and on farms;[10] whereas other fairies are usually said to reside in places of remote wilderness.[10] Brownies are usually regarded as harmless, unless they are angered;[10] other types of folkloric fairies, however, are typically seen as dark and dangerous.[10] Finally, brownies are unusual for their solitary nature, since most other types of fairies are often thought to live in large groups.[10]

Briggs notes that brownies are frequently associated with the dead[13] and states that, like the banshee in Irish folklore, "a good case" could be made for brownies to be classified as ghosts.[3] Nonetheless, she rejects this idea, commenting that the Brownie has "an adaptability, individuality and a homely tang which forbids one to think of him as merely a lingering and reminiscent image."[3]

In seventeenth-century Scotland, brownies were sometimes regarded as a kind of demon.[61]King James VI and I describes the brownie as a demon in his 1597 treatise Daemonologie:[12][38][61]

... among the first kinde of spirites that I speak of, appeared in the time of Papistrie and blindness, and haunted divers houses, without doing any evill, but as it were necessarie turnes up and down the house: and this pirit they called Brownie in our language, who appeared like a rough-man: yea, some were so blinded, as to believe that their house was all the sonsier, as they called it, that such spirites resorted there.[62]

Functionalist analysis

The folklorist L. F. Newman states that the image of the brownie fits well into a Functionalist analysis of the "old, generous rural economy" of pre-Industrial Britain,[33] describing him as the epitome of what a good household servant of the era was supposed to be.[33] Belief in brownies could be exploited by both masters and servants.[63] The servants could blame the brownie for messes, breakages, and strange noises heard at night.[64] Meanwhile, the masters of the house who employed them could use stories of the brownie to convince their servants to behave by telling them that the brownie would punish servants who were idle and reward those who performed their duties vigilantly.[64] According to Susan Stewart, brownies also resolved the problem that human storytellers faced of the unending repetition and futility of labour.[6] As immortal spirits, brownies could not be worn out nor revitalized by working, so their work became seen as simply part of "a perpetual cycle that is akin to the activities of Nature herself."[6]

Outside of folklore

Early literary appearances

In James Hogg's 1818 novel The Brownie of Bodsbeck, the eponymous "brownie" turns out to be John Brown, the leader of the Covenanters, a persecuted Scottish Presbyterian movement.[65] An illegal meeting of Covenanters is shown in this painting, Covenanters in a Glen by Alexander Carse.

An entity referred to as a "drudging goblin" or the "Lubbar Fend" is described in lines 105 to 114 of John Milton's 1645 pastoral poem L'Allegro.[6][47] The "goblin" churns butter, brews drinks, makes dough rise, sweeps the floor, washes the dishes, and lays by the fire.[6] According to Briggs, like most other early brownies, Milton's Lubbar Fend was probably envisioned as human-sized or larger.[16] In many early literary appearances, the brownie turns out to be an ordinary person.[66] The Scottish novelist James Hogg incorporated brownie folklore into his novel The Brownie of Bodsbeck (1818).[67][65] The novel is set in 1685, when the Covenanters, a Scottish Presbyterian movement, were being persecuted.[65] Food goes missing from the farm of Walter of Chaplehope, leading villagers to suspect it is the "brownie of Bodsbeck".[65][67] In the end, it turns out that the "brownie" was actually John Brown, the leader of the Covenanters.[65]

Hogg later wrote about brownies in his short story "The Brownie of Black Haggs" (1828).[66][68] In this story, the evil Lady Wheelhope orders that any of her male servants who openly practices any form of religion must be given over to the military and shot.[65] Female servants who practiced religion are discretely poisoned.[65] A single mysterious servant named Merodach stands up to her.[65] Merodach is described as having "the form of a boy, but the features of one a hundred years old" and his eyes "bear a strong resemblance to the eyes of a well-known species of monkey."[65] Characters in the novel believe Merodach to be a brownie, although others claim that he is a "mongrel, between a Jew and an ape... a wizard... a kelpie, or a fairy".[69] Like folkloric brownies, Merodach's religion is overtly pagan and he detests the sight of the Bible.[69] He also refuses to accept any form of payment.[69] Lady Wheelhope hates him and attempts to kill him,[69] but all her efforts mysteriously backfire, instead resulting in the deaths of those she loves.[69] The novel never reveals whether Merodach is actually of supernatural origin or if he is merely a peculiar-looking servant.[68]Charlotte and Emily Brontë were both familiar with Hogg's stories[69] and his portrayal of Merodach may have greatly influenced Emily's portrayal of her character Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights (1847).[69] Brownies are also briefly referenced in Charlotte's novel Villette (1853).[70]

The late nineteenth century saw the growth and profusion of children's literature, which often incorporated fantasy.[71] Brownies in particular were often thought of as especially appealing to children.[66]Juliana Horatia Ewing incorporated brownie folklore remembered from her childhood into her short story "The Brownies", first published in 1865 in The Monthly Packet[66] and later incorporated into her 1871 collection of short stories The Brownies and Other Tales.[71][67] In the story, a selfish boy seeks a brownie to do his chores for him because he is too lazy to do them himself.[67] A wise old owl tells him that brownies do not really exist and the only real brownies are good little children who do chores without being asked.[67][72] The boy goes home and convinces his younger brother in join him in becoming the new household "brownies".[67] Ewing's short story inspired the idea of calling helpful children "brownies".[66][67][72]

Mass marketing

Illustration of a brownie by Palmer Cox from his Brownies Around the World (1894). The popularity of Cox's poems and illustrations cemented brownies as an element of North American children's literature.[66]

The Canadian American children's writer Palmer Cox helped promote brownies in North America through his illustrated poems about them published in St. Nicholas Magazine.[66][73] Cox portrayed brownies as "tiny elf-like figures who often took on tasks en masse".[74] These poems and illustrations were later collected and published in his book The Brownies: Their Book in 1887, which became the first of several such collections.[66][74] In the 1890s, so-called "brownie-mania" swept across the United States.[73] Cox effectively licensed out his brownie characters rather than selling them, something which he was among the first to do.[73][75] He and his many business collaborators were able to market brownie-themed tie-in merchandise, including boots, cigars, stoves, dolls, and silverware.[73][75]

The popularity of Cox's poems, illustrations, and tie-in products cemented brownies as an element of North American children's literature and culture.[66][73][74] Meanwhile, Cox could not copyright the name "brownie" because it was a creature from folklore, so unauthorized "brownie" products began to flood the market as well.[76] The widespread "brownie" merchandise inspired George Eastman to name his low-cost camera "Brownie".[76] In 1919, Juliette Gordon Low adopted "Brownies" as the name for the lowest age group in her organization of "Girl Guides" on account of Ewing's short story.[66][77]

A brownie character named "Big Ears" appears in Enid Blyton's Noddy series of children's books,[72] in which he is portrayed as living in a mushroom house just outside the village of Toytown.[72] In Blyton's Book of Brownies (1926), a mischievous trio of brownies named Hop, Skip, and Jump attempt to sneak into a party hosted by the King of Fairyland by pretending to be Twirly-Whirly, the Great Conjuror from the Land of Tiddlywinks, and his two assistants.[72]

Modern fantasy

George MacDonald incorporated features of Scottish brownie lore in his nineteenth-century works The Princess and the Goblin and Sir Gibbie—his brownies have no fingers on their hands.[71] Warrior brownies appear in the 1988 fantasy film Willow, directed by Ron Howard.[78] These brownies are portrayed as only a couple inches tall and are armed with bows and arrows.[78] Though they are initially introduced as the kidnappers of a human infant, they turn out to be benevolent.[78] Creatures known as "house elves" appear in the Harry Potter series of books by J. K. Rowling, published between 1997 and 2007.[72] Like the traditional brownies of folklore, house elves are loyal to their masters and may be released by a gift of clothing.[72] House elves also resemble brownies in appearance, being small, but they have larger heads and large, bat-like ears.[72] Rowling's books also include boggarts, which are sometimes traditionally described as brownies turned malevolent.[79]

A brownie named Thimbletack plays an important role in the children's fantasy book series The Spiderwick Chronicles,[80][78] written by Holly Black and Tony DiTerlizzi and published in five volumes from May 2003 to September 2004 by Simon & Schuster.[81] He lives inside the walls of the Spiderwick estate[80] and is only visible when he wishes to be seen.[80] He is described as "a little man about the size of a pencil" with eyes "black and beetles" and a nose that is "large and red".[78] When angered, Thimbletack transforms into a malicious boggart.[78][80] The series became an international bestseller and was translated into thirty languages.[81]A film adaptation of the same name was released in 2008.[82]

See also

- Changeling

Domovoi (Slavic)

Haltija/Tonttu (Finnish)

Heinzelmännchen (German)

Household deity- Lithuanian household gods (list)

Jack o' the bowl (Swiss)

Koro-pok-guru (Japanese)- Meg Mullach

Tomte (Scandinavian)- Wirry-cow

Notes

^ Sometimes, however, pixies or other trooping fairies do the work of a brownie,[13] especially in the West Country.[15]

References

^ "Dictionary of the Scots Language :: SND :: Broonie n.1". www.dsl.ac.uk..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ abc McNeill 1977, p. 123.

^ abcdefghi Briggs 1967, p. 47.

^ ab Stewart 2007, pp. 110–111.

^ ab Silver 2005, p. 205.

^ abcdefghijklmnop Stewart 2007, p. 111.

^ Briggs 1967, pp. 47–48.

^ Briggs 1967, pp. 39–40.

^ abcdefghijklm Briggs 1967, p. 40.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuv Simpson & Roud 2000, p. 110.

^ abcdefg Monaghan 2004, p. 62.

^ abcdefghijklmn Alexander 2013, p. 64.

^ abc Briggs 1967, pp. 46–47.

^ abcdefgh Briggs 1967, p. 35.

^ abcdefghijklm Briggs 1967, p. 33.

^ abcdefghijklmn Briggs 1967, p. 46.

^ Briggs 1967, pp. 35, 46.

^ Henderson & Cowan 2001, p. 16.

^ Monaghan 2004, p. 322.

^ Silver 2005, pp. 205–206.

^ abcd Miller 2008, p. 151.

^ ab Keightley, Thomas (1870). "The Brownie". The Fairy Mythology. London: H. G. Bohn.

^ Silver 2005, p. 206.

^ abcdefg Briggs 1967, p. 42.

^ Briggs 1967, pp. 42–43.

^ ab Dorson 2001, p. 180.

^ abcde Briggs 1967, p. 41.

^ ab Briggs 1967, pp. 41–42.

^ abc Simpson & Roud 2000, pp. 110–111.

^ ab Briggs 1967, pp. 38–41.

^ Alexander 2013, pp. 64–65.

^ abcd Alexander 2013, p. 65.

^ abcdefghi Simpson & Roud 2000, p. 111.

^ Briggs 1967, pp. 37, 40–41.

^ abcdefghijklmno Briggs 1967, p. 38.

^ abcdefghijk Briggs 1967, p. 43.

^ ab Briggs 1967, pp. 43–44.

^ abcdef Simpson & Roud 2000, p. 109.

^ Briggs 1967, pp. 33–39.

^ abcdefg Briggs 1967, p. 37.

^ Briggs 1967, pp. 37–38.

^ abcde Briggs 1967, p. 36.

^ ab Briggs 1967, pp. 36–37.

^ abcdefgh Briggs 1967, p. 45.

^ abcdef Briggs 1967, p. 44.

^ ab Monaghan 2004, p. 292.

^ abcd Germanà 2014, p. 61.

^ ab Monaghan 2004, p. 420.

^ abcd Dacre 2011, p. 105.

^ Campbell, John Gregorson (1900), Superstitions Of The Highlands And Islands Of Scotland, Glasgow, Scotland: James MacLehose and Sons, p. 194

^ abc McNeill 1977, p. 128.

^ West 2007, p. 294.

^ abcde McNeill 1977, p. 126.

^ West 2007, pp. 292–294.

^ abcdefg McNeill 1977, p. 127.

^ Briggs, Katharine (1977) [1976]. An Encyclopedia of Fairies, Hobgoblins, Brownies, Bogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures. Middlesex, United Kingdom: Penguin. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-14-004753-0.

^ abc Briggs 1967, pp. 32–33.

^ Dorson 2001, pp. 120–121.

^ Briggs 1967, p. 32.

^ Simpson & Roud 2000, pp. 109–110.

^ ab Miller 2008, p. 148.

^ King James VI and I, Daemonology

^ Simpson & Roud 2000, pp. 111–112.

^ ab Simpson & Roud 2000, p. 112.

^ abcdefghi Germanà 2014, p. 62.

^ abcdefghij Ashley 1999, p. 316.

^ abcdefg Margerum 2005, p. 92.

^ ab Germanà 2014, pp. 62–63.

^ abcdefg Germanà 2014, p. 63.

^ Germanà 2014, pp. 63–64.

^ abc Briggs, Katharine M. (1972). "Folklore in Nineteenth-Century English Literature". Folklore. 83 (3): 194–209. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1972.9716469. JSTOR 1259545.

^ abcdefgh Germanà 2014, p. 64.

^ abcde Margerum 2005, pp. 92–93.

^ abc Nelson & Chasar 2012, p. 143.

^ ab Nelson & Chasar 2012, pp. 143–144.

^ ab Margerum 2005, p. 93.

^ Monaghan 2004, pp. 61–62.

^ abcdef Germanà 2014, p. 65.

^ Germanà 2014, pp. 64–65.

^ abcd Heller 2014, p. 190.

^ ab Heller 2014, p. 188.

^ Heller 2014, pp. 188–190.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

Alexander, Marc (2013) [2002], Sutton Companion to British Folklore, Myths & Legends, Stroud, England: The History Press, ISBN 978-0-7509-5427-3

Ashley, Mike (1999) [1997], "Elves", The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, New York City, New York: St. Martin's Griffin, p. 316, ISBN 978-0-312-19869-5

Briggs, Katharine Mary (1967), The Fairies in Tradition and Literature, New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-28601-5

Dacre, Michael (2011), Devonshire Folk Tales, Stroud, England: The History Press, ISBN 978-0-7524-7033-7

Dorson, Richard Mercer (2001) [1968], History of British Folklore, I, New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-20476-7

Germanà, Monica (2014), "Brownie", in Weinstock, Jeffrey Andrew, The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters, New York City, New York and London, England: Ashgate Publishing, pp. 61–65, ISBN 978-1-4094-2563-2

Heller, Erga (2014), "When Fantasy Becomes a Real Issue: On Local and Global Aspects of Literary Translation/Adaptation, Subtitling and Dubbing Films for the Young", in Abend-David, Dror, Media and Translation: An Interdisciplinary Approach, New York City, New York and London, England: Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 978-1-6235-6101-7

Henderson, Lizanne; Cowan, Edward J. (2001), Scottish Fairy Belief: A History, East Linton, East Lothian, Scotland: Tuckwell Press, p. 16, ISBN 978-1-8623-2190-8

Margerum, Eileen (2005), "Palmer Cox: Telling Stories", in Anderson, Mark Cronland; Blayer, Irene Maria F., Interdisciplinary and Cross-Cultural Narratives in North America, New York City, New York: Peter Lang, ISBN 978-0-8204-7409-0, ISSN 1056-3970

McNeill, Florence Marian (1977) [1957], The Silver Bough: Scottish Folk-lore and Folk-belief, 1, Glasgow, Scotland: William Maclellan, Ltd., ISBN 9780853351610

Miller, Joyce (2008), "Men in Black: Appearances of the Devil in Early Modern Witchcraft Discourse", in Goodare, Julian; Martin, Lauren; Miller, Joyce, Witchcraft and Belief in Early Modern Scotland, New York City, New York: Palgrave MacMillan, doi:10.1057/9780230591400, ISBN 978-0-230-59140-0

Monaghan, Patricia (2004), The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore, Facts On File, New York City, New York: InfoBase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-4524-2

Nelson, Cary; Chasar, Mike (2012), "American Advertising", in Bold, Christine, The Oxford History of Popular Print Culture: Volume Six: US Popular Print Culture 1860–1920, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-923406-6

Silver, Carole G. (2005), "Fairies and Elves: Motifs F200-F399", in Garry, Jane; El-Shamy, Hasan, Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature: A Handbook, New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge, pp. 203–210, ISBN 978-0-7656-1260-1

Simpson, Jacqueline; Roud, Steve (2000), A Dictionary of English Folklore: An Engrossing Guide to English Folklore and Traditions, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-210019-1

Stewart, Susan (2007), "Reading a Drawer", in Caicco, Gregory, Architecture, Ethics, and the Personhood of Place, Hanover, Germany and London, England: University Press of New England, ISBN 978-1-58465-653-1

West, Martin Litchfield (2007), Indo-European Poetry and Myth, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-928075-9

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brownie (folklore). |