Iberian Peninsula

Native names

| |

|---|---|

Satellite image of the Iberian Peninsula. | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Southwestern Europe |

| Coordinates | 40°30′N 4°00′W / 40.500°N 4.000°W / 40.500; -4.000Coordinates: 40°30′N 4°00′W / 40.500°N 4.000°W / 40.500; -4.000 |

| Area | 596,740 km2 (230,400 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 3,478 m (11,411 ft) |

| Highest point | Mulhacén |

| Administration | |

Andorra | |

| Capital and largest town | Andorra la Vella |

| Area covered | 468 km2 (181 sq mi; 6999100000000000000♠0.1%) |

Portugal | |

| Capital and largest city | Lisbon |

| Area covered | 89,015 km2 (34,369 sq mi; 7001149000000000000♠14.9%) |

Spain | |

| Capital and largest city | Madrid |

| Area covered | 492,175 km2 (190,030 sq mi; 7001825000000000000♠82.5%) |

Gibraltar .mw-parser-output .noboldfont-weight:normal (United Kingdom) | |

| Capital city | Gibraltar |

| Largest district | Westside |

| Area covered | 7 km2 (2.7 sq mi; 5000000000000000000♠0%) |

France | |

| Largest commune | Font-Romeu-Odeillo-Via |

| Area covered | 33,563 km2 (12,959 sq mi; 7000560000000099999♠5.6%) |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | Iberian |

| Population | About 57,2 million |

The Iberian Peninsula /aɪˈbɪəriən/,[a] also known as Iberia,[b] is located in the southwest corner of Europe. The peninsula is principally divided between Spain and Portugal, comprising most of their territory. It also includes Andorra, small areas of France, and the British overseas territory of Gibraltar. With an area of approximately 596,740 square kilometres (230,400 sq mi)[1]), it is the second largest European peninsula, after the Scandinavian.

Contents

1 Name

1.1 Greek name

1.2 Roman names

2 Etymology

3 Prehistory

3.1 Palaeolithic

3.2 Neolithic

3.3 Chalcolithic

3.4 Bronze Age

4 Proto-history

5 History

5.1 Roman rule

5.2 Germanic kingdoms

5.3 Islamic Caliphate

5.4 Reconquest

5.5 Post-reconquest

6 Geography and geology

6.1 Coastline

6.2 Rivers

6.3 Mountains

6.4 Geology

6.5 Climate

7 Major modern countries

7.1 Major urban areas

7.2 Major cities

8 Ecology

8.1 Forests

8.2 East Atlantic flyway

9 Languages

10 Economy

11 See also

12 Notes

13 References

14 External links

Name

Iberian Peninsula and southern France, satellite photo on a cloudless day in March 2014

Greek name

The word Iberia is a noun adapted from the Latin word "Hiberia" originated by the Ancient Greek word Ἰβηρία (Ibēríā) by Greek geographers under the rule of the Roman Empire to refer to what is known today in English as the Iberian Peninsula.[2] At that time, the name did not describe a single political entity or a distinct population of people.[3]Strabo's 'Iberia' was delineated from Keltikē (Gaul) by the Pyrenees[4] and included the entire land mass southwest (he says "west") of there.[5] With the fall of the Roman Empire and the establishment of the new Castillian language in Spain, the word "Iberia" appeared for the first time in use as a direct 'descendant' of the Greek word "Ἰβηρία" and the Roman word "Hiberia".

The ancient Greeks reached the Iberian Peninsula, of which they had heard from the Phoenicians, by voyaging westward on the Mediterranean.[6]Hecataeus of Miletus was the first known to use the term Iberia, which he wrote about circa 500 BC.[7]Herodotus of Halicarnassus says of the Phocaeans that "it was they who made the Greeks acquainted with... Iberia."[8] According to Strabo,[9] prior historians used Iberia to mean the country "this side of the Ἶβηρος (Ibēros)" as far north as the river Rhône in France, but currently they set the Pyrenees as the limit. Polybius respects that limit,[10] but identifies Iberia as the Mediterranean side as far south as Gibraltar, with the Atlantic side having no name. Elsewhere[11] he says that Saguntum is "on the seaward foot of the range of hills connecting Iberia and Celtiberia."

Strabo[12] refers to the Carretanians as people "of the Iberian stock" living in the Pyrenees, who are distinct from either Celts or Celtiberians.

Roman names

According to Charles Ebel, the ancient sources in both Latin and Greek use Hispania and Hiberia (Greek: Iberia) as synonyms. The confusion of the words was because of an overlapping in political and geographic perspectives. The Latin word Hiberia, similar to the Greek Iberia, literally translates to "land of the Hiberians". This word was derived from the river Ebro, which the Romans called Hiberus. Hiber (Iberian) was thus used as a term for peoples living near the river Ebro.[4][13] The first mention in Roman literature was by the annalist poet Ennius in 200 BC.[14][15][16]Virgil refers to the Ipacatos Hiberos ("restless Iberi") in his Georgics.[17] The Roman geographers and other prose writers from the time of the late Roman Republic called the entire peninsula Hispania.

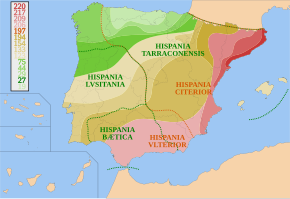

As they became politically interested in the former Carthaginian territories, the Romans began to use the names Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior for 'near' and 'far' Hispania. At the time Hispania was made up of three Roman provinces: Hispania Baetica, Hispania Tarraconensis, and Hispania Lusitania. Strabo says[9] that the Romans use Hispania and Iberia synonymously, distinguishing between the near northern and the far southern provinces. (The name "Iberia" was ambiguous, being also the name of the Kingdom of Iberia in the Caucasus.)

Whatever language may generally have been spoken on the peninsula soon gave way to Latin, except for that of the Vascones, which was preserved as a language isolate by the barrier of the Pyrenees.

Etymology

Northeast Iberian script from Huesca.

The Iberian Peninsula has always been associated with the Ebro, Ibēros in ancient Greek and Ibērus or Hibērus in Latin. The association was so well known it was hardly necessary to state; for example, Ibēria was the country "this side of the Ibērus" in Strabo. Pliny goes so far as to assert that the Greeks had called "the whole of Spain" Hiberia because of the Hiberus River.[18] The river appears in the Ebro Treaty of 226 BC between Rome and Carthage, setting the limit of Carthaginian interest at the Ebro. The fullest description of the treaty, stated in Appian,[19] uses Ibērus. With reference to this border, Polybius[20] states that the "native name" is Ibēr, apparently the original word, stripped of its Greek or Latin -os or -us termination.

The early range of these natives, which geographers and historians place from today's southern Spain to today's southern France along the Mediterranean coast, is marked by instances of a readable script expressing a yet unknown language, dubbed "Iberian." Whether this was the native name or was given to them by the Greeks for their residence on the Ebro remains unknown. Credence in Polybius imposes certain limitations on etymologizing: if the language remains unknown, the meanings of the words, including Iber, must also remain unknown. In modern Basque, the word ibar[21] means "valley" or "watered meadow", while ibai[21] means "river", but there is no proof relating the etymology of the Ebro River with these Basque names.

Prehistory

Schematic rock art from the Iberian Peninsula.

Iberian Late Bronze Age since c. 1300 BC

Palaeolithic

The Iberian Peninsula has been inhabited for at least 1.2 million years as remains found in the sites in the Atapuerca Mountains demonstrate. Among these sites is the cave of Gran Dolina, where six hominin skeletons, dated between 780,000 and one million years ago, were found in 1994. Experts have debated whether these skeletons belong to the species Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, or a new species called Homo antecessor.

Around 200,000 BP, during the Lower Paleolithic period, Neanderthals first entered the Iberian Peninsula. Around 70,000 BP, during the Middle Paleolithic period, the last glacial event began and the Neanderthal Mousterian culture was established. Around 37,000 BP, during the Upper Paleolithic, the Neanderthal Châtelperronian cultural period began. Emanating from Southern France, this culture extended into the north of the peninsula. It continued to exist until around 30,000 BP, when Neanderthal man faced extinction.

About 40,000 years ago, anatomically modern humans entered the Iberian Peninsula from Southern France.[22] Here, this genetically homogeneous population (characterized by the M173 mutation in the Y chromosome), developed the M343 mutation, giving rise to Haplogroup R1b, still the most common in modern Portuguese and Spanish males.[23] On the Iberian Peninsula, modern humans developed a series of different cultures, such as the Aurignacian, Gravettian, Solutrean and Magdalenian cultures, some of them characterized by the complex forms of the art of the Upper Paleolithic.

Neolithic

During the Neolithic expansion, various megalithic cultures developed in the Iberian Peninsula.[24] An open seas navigation culture from the east Mediterranean, called the Cardium culture, also extended its influence to the eastern coasts of the peninsula, possibly as early as the 5th millennium BC. These people may have had some relation to the subsequent development of the Iberian civilization.

Chalcolithic

In the Chalcolithic (c. 3000 BC), a series of complex cultures developed that would give rise to the peninsula's first civilizations and to extensive exchange networks reaching to the Baltic, Middle East and North Africa. Around 2800 – 2700 BC, the Beaker culture, which produced the Maritime Bell Beaker, probably originated in the vibrant copper-using communities of the Tagus estuary in Portugal and spread from there to many parts of western Europe.[25]

Bronze Age

Bronze Age cultures developed beginning c.1800 BC,[26] when the civilization of Los Millares was followed by that of El Argar.[27][28] From this centre, bronze technology spread to other cultures like the Bronze of Levante, South-Western Iberian Bronze and Las Cogotas.

In the Late Bronze Age, the urban civilisation of Tartessos developed in the area of modern western Andalusia, characterized by Phoenician influence and using the Southwest Paleohispanic script for its Tartessian language, not related to the Iberian language.

Early in the first millennium BC, several waves of Pre-Celts and Celts migrated from Central Europe, thus partially changing the peninsula's ethnic landscape to Indo-European-speaking in its northern and western regions. In Northwestern Iberia (modern Northern Portugal, Asturias and Galicia), a Celtic culture developed, the Castro culture, with a large number of hill forts and some fortified cities.

Proto-history

By the Iron Age, starting in the 7th century BC, the Iberian Peninsula consisted of complex agrarian and urban civilizations, either Pre-Celtic or Celtic (such as the Lusitanians, Celtiberians, Gallaeci, Astures, Celtici and others), the cultures of the Iberians in the eastern and southern zones and the cultures of the Aquitanian in the western portion of the Pyrenees.

The seafaring Phoenicians, Greeks and Carthaginians successively settled along the Mediterranean coast and founded trading colonies there over a period of several centuries. Around 1100 BC, Phoenician merchants founded the trading colony of Gadir or Gades (modern day Cádiz) near Tartessos. In the 8th century BC, the first Greek colonies, such as Emporion (modern Empúries), were founded along the Mediterranean coast on the east, leaving the south coast to the Phoenicians. The Greeks coined the name Iberia, after the river Iber (Ebro). In the sixth century BC, the Carthaginians arrived in the peninsula while struggling with the Greeks for control of the Western Mediterranean. Their most important colony was Carthago Nova (modern-day Cartagena, Spain).

History

Roman rule

Roman conquest: 220 BC - 19 BC

In 218 BC, during the Second Punic War against the Carthaginians, the first Roman troops invaded the Iberian Peninsula; however, it was not until the reign of Augustus that it was annexed after 200 years of war with the Celts and Iberians. The result was the creation of the province of Hispania. It was divided into Hispania Ulterior and Hispania Citerior during the late Roman Republic, and during the Roman Empire, it was divided into Hispania Tarraconensis in the northeast, Hispania Baetica in the south and Lusitania in the southwest.

Hispania supplied the Roman Empire with silver, food, olive oil, wine, and metal. The emperors Trajan, Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius, and Theodosius I, the philosopher Seneca the Younger, and the poets Martial and Lucan were born from families living on the Iberian Peninsula.

During their 600-year rule in the Iberian Peninsula, the Romans introduced the Latin language that influenced many of the languages that exist today in the Iberian peninsula.

Germanic kingdoms

Germanic and Byzantine rule c.560

In the early fifth century, Germanic peoples invaded the peninsula, namely the Suebi, the Vandals (Silingi and Hasdingi) and their allies, the Alans. Only the kingdom of the Suebi (Quadi and Marcomanni) would endure after the arrival of another wave of Germanic invaders, the Visigoths, who conquered all of the Iberian Peninsula and expelled or partially integrated the Vandals and the Alans. The Visigoths eventually conquered the Suebi kingdom and its capital city, Bracara (modern day Braga), in 584–585. They would also conquer the province of the Byzantine Empire (552–624) of Spania in the south of the peninsula and the Balearic Islands.

Islamic Caliphate

Islamic rule: al-Andalus c.1000

In 711, a Muslim army invaded the Visigothic Kingdom in Hispania. Under Tariq ibn Ziyad, the Islamic army landed at Gibraltar and, in an eight-year campaign, occupied all except the northern kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula in the Umayyad conquest of Hispania. Al-Andalus (Arabic: الإندلس, tr. al-ʾAndalūs, possibly "Land of the Vandals"),[29][30] is the Arabic name given to what is today southern Spain by its Muslim Berber and Arab occupiers.

From the 8th–15th centuries, only the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula was part of the Islamic world. It became a center of culture and learning, especially during the Caliphate of Córdoba, which reached its height of its power under the rule of Abd-ar-Rahman III and his successor al-Hakam II.[31] The Muslims, who were initially Arabs and Berbers, included some local converts, the so-called Muladi.[32] The Muslims were referred to by the generic name, Moors[33] The Reconquista gained momentum on c. 718, when the Christian Asturians opposed the Moors.

Reconquest

Many of the ousted Gothic nobles took refuge in the unconquered north Kingdom of Asturias. From there, they aimed to reconquer their lands from the Moors; this war of reconquest is known as the Reconquista. Christian and Muslim kingdoms fought and allied among themselves. The fighting was characterised by raids into Islamic territory with the intent of destroying crops, orchards, and villages, and of killing and enslaving any Muslims they came across. Christian forces were usually better armoured than their Muslim counterparts, with noble and non-noble milites and cavallers wearing mail hauberks, separate mail coifs and metal helmets, and armed with maces, cavalry axes, sword and lances.[34]

Henry II kills his predecessor as King of Castile and León, Peter the Cruel

During the Middle Ages, the peninsula housed many small states including the Kingdom of Castile, Kingdom of Aragon, Kingdom of Navarre, Kingdom of León and the Kingdom of Portugal. The Muslims were driven out of Portugal by 1249. By the end of the 13th century, the Spanish Reconquista was largely completed.

The 14th century was a period of great internal changes in the Spanish kingdoms. After the death of Peter the Cruel of Castile (reigned 1350–69), the House of Trastámara succeeded to the throne in the person of Peter's half brother, Henry II (reigned 1369–79). In the kingdom of Aragón, following the death without heirs of John I (reigned 1387–96) and Martin I (reigned 1396–1410), a prince of the House of Trastámara, Ferdinand I (reigned 1412–16), succeeded to the Aragonese throne.[35]

During this period the Jews in Spain became very numerous and acquired great power;[36] they were not only the physicians, but also the treasurers of the kings. Don Jusaph de Ecija administered the revenues of Alfonso XI, and Samuel ha-Levi was chief favourite of Peter the Cruel. The Jews of Toledo then set on foot their migration in protest against the laws of Alfonso X (Las Siete Partidas), which prohibited the building of new synagogues.

After the accession of Henry of Trastámara to the throne, the populace, exasperated by the preponderance of Jewish influence, perpetrated a massacre of Jews at Toledo. In 1391, mobs went from town to town throughout Castile and Aragon, killing an estimated 50,000–100,000 Jews.[37][38][39][40][41][42][43] Women and children were sold as slaves to Muslims, and many synagogues were converted into churches. According to Hasdai Crescas, about 70 Jewish communities were destroyed.[44]

The last Muslim stronghold, Granada, was conquered by a combined Castilian and Aragonese force in 1492. As many as 100,000 Moors died or were enslaved in the military campaign, while 200,000 fled to North Africa.[45] Muslims and Jews throughout the period were variously tolerated or shown intolerance in different Christian kingdoms. After the fall of Granada, all Muslims and Jews were ordered to convert to Christianity or face expulsion—as many as 200,000 Jews were expelled from Spain.[46][47][48][49] Historian Henry Kamen estimates that some 25,000 Jews died en route from Spain.[50] The Jews were also expelled from Sicily and Sardinia, which were under Aragonese rule, and an estimated 37,000 to 100,000 Jews left.[51]

In 1497, King Manuel I of Portugal forced all Jews in his kingdom to convert or leave. That same year he expelled all Muslims that were not slaves,[52] and in 1502 the Catholic Monarchs followed suit, imposing the choice of conversion to Christianity or exile and loss of property. Many Jews and Muslims fled to North Africa and the Ottoman Empire, while others publicly converted to Christianity and became known respectively as Marranos (Spanish for pig) and Moriscos (after the old term Moors).[53] However, many of these continued to practice their religion in secret. The Moriscos revolted several times and were ultimately forcibly expelled from Spain in the early 17th century. From 1609–14, over 300,000 Moriscos were sent on ships to North Africa and other locations, and, of this figure, around 50,000 died resisting the expulsion, and 60,000 died on the journey.[54][55][56]

Map of Spain and Portugal, Atlas historique, dated approximately 1705–1739, of H.A. Chatelain

Post-reconquest

The small states gradually amalgamated over time. Portugal was the exception, except for a brief period (1580–1640) during which the whole peninsula was united politically under the Iberian Union. After that point, the modern position was reached and the peninsula now consists of the countries of Spain and Portugal (excluding their islands—the Portuguese Azores and Madeira and the Spanish Canary Islands and Balearic Islands; and the Spanish exclaves of Ceuta and Melilla), Andorra, French Cerdagne and Gibraltar.

Geography and geology

The Iberian Peninsula is the westernmost of the three major southern European peninsulas—the Iberian, Italian, and Balkan.[57] It is bordered on the southeast and east by the Mediterranean Sea, and on the north, west, and southwest by the Atlantic Ocean. The Pyrenees mountains are situated along the northeast edge of the peninsula, where it adjoins the rest of Europe. Its southern tip is very close to the northwest coast of Africa, separated from it by the Strait of Gibraltar and the Mediterranean Sea.

The Iberian Peninsula extends from the southernmost extremity at Punta de Tarifa (36°00′15″N 5°36′37″W / 36.00417°N 5.61028°W / 36.00417; -5.61028) to the northernmost extremity at Punta de Estaca de Bares (43°47′38″N 7°41′17″W / 43.79389°N 7.68806°W / 43.79389; -7.68806) over a distance between lines of latitude of about 865 km (537 mi) based on a degree length of 111 km (69 mi) per degree, and from the westernmost extremity at Cabo da Roca (38°46′51″N 9°29′54″W / 38.78083°N 9.49833°W / 38.78083; -9.49833) to the easternmost extremity at Cap de Creus (42°19′09″N 3°19′19″E / 42.31917°N 3.32194°E / 42.31917; 3.32194) over a distance between lines of longitude at 40° N latitude of about 1,155 km (718 mi) based on an estimated degree length of about 90 km (56 mi) for that latitude. The irregular, roughly octagonal shape of the peninsula contained within this spherical quadrangle was compared to an ox-hide by the geographer Strabo.[58]

About three quarters of that rough octagon is the Meseta Central, a vast plateau ranging from 610 to 760 m in altitude.[59] It is located approximately in the centre, staggered slightly to the east and tilted slightly toward the west (the conventional centre of the Iberian Peninsula has long been considered Getafe just south of Madrid). It is ringed by mountains and contains the sources of most of the rivers, which find their way through gaps in the mountain barriers on all sides.

Coastline

The coastline of the Iberian Peninsula is 3,313 km (2,059 mi), 1,660 km (1,030 mi) on the Mediterranean side and 1,653 km (1,027 mi) on the Atlantic side.[60] The coast has been inundated over time, with sea levels having risen from a minimum of 115–120 m (377–394 ft) lower than today at the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) to its current level at 4,000 years BP.[61] The coastal shelf created by sedimentation during that time remains below the surface; however, it was never very extensive on the Atlantic side, as the continental shelf drops rather steeply into the depths. An estimated 700 km (430 mi) length of Atlantic shelf is only 10–65 km (6.2–40.4 mi) wide. At the 500 m (1,600 ft) isobath, on the edge, the shelf drops off to 1,000 m (3,300 ft).[62]

The submarine topography of the coastal waters of the Iberian Peninsula has been studied extensively in the process of drilling for oil. Ultimately, the shelf drops into the Bay of Biscay on the north (an abyss), the Iberian abyssal plain at 4,800 m (15,700 ft) on the west, and Tagus abyssal plain to the south. In the north, between the continental shelf and the abyss, is an extension called the Galicia Bank, a plateau that also contains the Porto, Vigo, and Vasco da Gama seamounts, which form the Galicia interior basin. The southern border of these features is marked by Nazaré Canyon, which splits the continental shelf and leads directly into the abyss.

Rivers

Major rivers of the Iberian Peninsula: Miño / Minho, Duero / Douro, Tajo / Tejo, Guadiana, Guadalquivir, Segura, Júcar / Xúquer and Ebro / Ebre.

The major rivers flow through the wide valleys between the mountain systems. These are the Ebro, Douro, Tagus, Guadiana and Guadalquivir.[63][64] All rivers in the Iberian Peninsula are subject to seasonal variations in flow.

The Tagus is the longest river on the peninsula and, like the Douro, flows westwards with its lower course in Portugal. The Guadiana river bends southwards and forms the border between Spain and Portugal in the last stretch of its course.

Mountains

The terrain of the Iberian Peninsula is largely mountainous.[65] The major mountain systems are:

- The Pyrenees and their foothills, the Pre-Pyrenees, crossing the isthmus of the peninsula so completely as to allow no passage except by mountain road, trail, coastal road or tunnel. Aneto in the Maladeta massif, at 3,404 m, is the highest point

- The Cantabrian Mountains along the northern coast with the massive Picos de Europa. Torre de Cerredo, at 2,648 m, is the highest point

- The Galicia/Trás-os-Montes Massif in the Northwest is made up of very old heavily eroded rocks.[66]Pena Trevinca, at 2,127 m, is the highest point

- The Sistema Ibérico, a complex system at the heart of the Peninsula, in its central/eastern region. It contains a great number of ranges and divides the watershed of the Tagus, Douro and Ebro rivers. Moncayo, at 2,313 m, is the highest point

- The Sistema Central, dividing the Iberian Plateau into a northern and a southern half and stretching into Portugal (where the highest point of Continental Portugal (1,993 m) is located in the Serra da Estrela). Pico Almanzor in the Sierra de Gredos is the highest point, at 2,592 m

- The Montes de Toledo, which also stretches into Portugal from the La Mancha natural region at the eastern end. Its highest point, at 1,603 m, is La Villuerca in the Sierra de Villuercas, Extremadura

- The Sierra Morena, which divides the watershed of the Guadiana and Guadalquivir rivers. At 1,332 m, Bañuela is the highest point

- The Baetic System, which stretches between Cádiz and Gibraltar and northeast towards Alicante Province. It is divided into three subsystems:

Prebaetic System, which begins west of the Sierra Sur de Jaén, reaching the Mediterranean Sea shores in Alicante Province. La Sagra is the highest point at 2,382 m.

Subbaetic System, which is in a central position within the Baetic Systems, stretching from Cape Trafalgar in Cádiz Province across Andalusia to the Region of Murcia.[67] The highest point, at 2,027 m (6,650 ft), is Peña de la Cruz in Sierra Arana.

Penibaetic System, located in the far southeastern area stretching between Gibraltar across the Mediterranean coastal Andalusian provinces. It includes the highest point in the peninsula, the 3,478 m high Mulhacén in the Sierra Nevada.[68]

Geology

Major Geologic Units of the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula contains rocks of every geological period from the Ediacaran to the Recent, and almost every kind of rock is represented. World-class mineral deposits can also be found there. The core of the Iberian Peninsula consists of a Hercynian cratonic block known as the Iberian Massif. On the northeast, this is bounded by the Pyrenean fold belt, and on the southeast it is bounded by the Baetic System. These twofold chains are part of the Alpine belt. To the west, the peninsula is delimited by the continental boundary formed by the magma-poor opening of the Atlantic Ocean. The Hercynian Foldbelt is mostly buried by Mesozoic and Tertiary cover rocks to the east, but nevertheless outcrops through the Sistema Ibérico and the Catalan Mediterranean System.

Climate

The Iberian peninsula has two dominant climate types. One of these is the oceanic climate seen in the Atlantic coastal region resulting in evenly temperatures with relatively cool summers. However, most of Portugal and Spain have a mediterranean climate with various precipitation and temperatures depending on latitude and position versus the sea. There are also more localized semi-arid climates in central Spain, with temperatures resembling a more continental mediterranean climate. In other extreme cases highland alpine climates such as in Sierra Nevada and areas with extremely low precitipation and desert climates or semi-arid climates such as the Almería[69] area, Murcia area and southern Alicante area. In the Spanish interior the hottest temperatures in Europe are found, with Córdoba averaging around 37 °C (99 °F) in July.[70] The Spanish mediterranean coast usually averages around 30 °C (86 °F) in summer. In sharp contrast A Coruña at the northern tip of Galicia has a summer daytime high average at just below 23 °C (73 °F).[71] This cool and wet summer climate is replicated throughout most of the northern coastline. Winter temperatures are more consistent throughout the peninsula, although frosts are common in the Spanish interior, even though daytime highs are usually above the freezing point. In Portugal, the warmest winters of the country are found in the area of Algarve, very similar to the ones from Huelva in Spain, while most of the Portuguese Atlantic coast has fresh and humid winters, similar to Galicia.

| Location | Coldest month | April | Warmest month | October |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Madrid | 9.8 °C (49.6 °F) 2.7 °C (36.9 °F) | 18.2 °C (64.8 °F) 7.7 °C (45.9 °F) | 32.1 °C (89.8 °F) 19.0 °C (66.2 °F) | 19.4 °C (66.9 °F) 10.7 °C (51.3 °F) |

Barcelona | 14.8 °C (58.6 °F) 8.8 °C (47.8 °F) | 19.1 °C (66.4 °F) 12.5 °C (54.5 °F) | 29.0 °C (84.2 °F) 23.1 °C (73.6 °F) | 22.5 °C (72.5 °F) 16.5 °C (61.7 °F) |

Valencia | 16.4 °C (61.5 °F) 7.1 °C (44.8 °F) | 20.8 °C (69.4 °F) 11.5 °C (52.7 °F) | 30.2 °C (86.4 °F) 21.9 °C (71.4 °F) | 24.4 °C (75.9 °F) 15.2 °C (59.4 °F) |

Seville | 16.0 °C (60.8 °F) 5.7 °C (42.3 °F) | 23.4 °C (74.1 °F) 11.1 °C (52.0 °F) | 36.0 °C (96.8 °F) 20.3 °C (68.5 °F) | 26.0 °C (78.8 °F) 14.4 °C (57.9 °F) |

Lisbon | 14.8 °C (58.6 °F) 8.3 °C (46.9 °F) | 19.8 °C (67.6 °F) 11.9 °C (53.4 °F) | 28.3 °C (82.9 °F) 18.6 °C (65.5 °F) | 22.5 °C (72.5 °F) 15.1 °C (59.2 °F) |

Porto | 13.8 °C (56.8 °F) 5.2 °C (41.4 °F) | 18.1 °C (64.6 °F) 9.1 °C (48.4 °F) | 25.7 °C (78.3 °F) 15.9 °C (60.6 °F) | 20.7 °C (69.3 °F) 12.2 °C (54.0 °F) |

Major modern countries

Political divisions of the Iberian Peninsula sorted by area:

Satellite image of Iberia at night

| Country/ Territory | Mainland population[74] | km2 | sq mi | % | Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Spain | 43,731,572 approx.[75] | 492,175 | 190,030 | 79% | occupies most of the peninsula |

Portugal | 10,047,083 approx.[76] | 89,015 | 34,369 | 15% | occupies most of the west of the peninsula |

France | 3,191,059 | 33,563 | 12,959 | 6% | French Cerdagne is on the south side of the Pyrenees mountain range, which runs along the border between Spain and France.[77][78][79] For example, the Segre river, which runs west and then south to meet the Ebro, has its source on the French side. The Pyrenees range is often considered the northeastern boundary of Iberian Peninsula, although the French coastline converges away from the rest of Europe north of the range. |

Andorra | 84,082 | 468 | 181 | 0.1% | a northern edge of the peninsula in the south side of the Pyrenees range between Spain and France |

Gibraltar (United Kingdom) | 29,431 | 7 | 3 | <0.1% | a British overseas territory near the southernmost tip of the peninsula |

Major urban areas

| Urban Area | Country | Region | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

Madrid | Spain | Community of Madrid | 6,321,398[80] |

Barcelona | Spain | Catalonia | 4,604,000[81] |

Lisbon | Portugal | Lisbon | 3,035,000[82] |

Porto | Portugal | Northern Portugal | 2,163,000[83] |

Valencia | Spain | Valencian Community | 1,564,145[84] |

The main metropolitan areas of the Iberian Peninsula are Madrid, Barcelona, Lisbon, Valencia, Porto, Seville, Bilbao, Guimarães, Málaga, Braga, Central Asturias (Gijón-Oviedo-Avilés), Alicante-Elche, Murcia and Coimbra.

Major cities

| List of cities in the Iberian Peninsula by population | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City/Town | Region & Country | Population (2011–12) | City/Town | Region & Country | Population (2011–12) | |||||

| 1 | Madrid | Madrid, Spain | 3,233,527 | 11 | Córdoba | Andalusia, Spain | 328,841 | |||

| 2 | Barcelona | Catalonia, Spain | 1,620,943 | 12 | Valladolid | Castile and León, Spain | 311,501 | |||

| 3 | Valencia | Valencia, Spain | 809,267 | 13 | Vigo | Galicia, Spain | 297,733 | |||

| 4 | Seville | Andalusia, Spain | 702,355 | 14 | Vila Nova de Gaia | Norte, Portugal | 288,749 | |||

| 5 | Zaragoza | Aragon, Spain | 679,624 | 15 | Gijón | Asturias, Spain | 277,554 | |||

| 6 | Málaga | Andalusia, Spain | 567,433 | 16 | L'Hospitalet | Catalonia, Spain | 257,057 | |||

| 7 | Lisbon | Lisboa, Portugal | 547,631 | 17 | A Coruña | Galicia, Spain | 246,146 | |||

| 8 | Murcia | Murcia, Spain | 441,354 | 18 | Vitoria-Gasteiz | Basque Country, Spain | 242,223 | |||

| 9 | Bilbao | Basque Country, Spain | 351,629 | 19 | Porto | Norte, Portugal | 237,591 | |||

| 10 | Alicante | Valencia, Spain | 334,678 | 20 | Granada | Andalusia, Spain | 237,540 | |||

Various other notable cities (populations given are for the cities proper not the metro areas or municipalities) are also present on the peninsula, such as: Elche (228,647) (part of the Alicante-Elche-Elda metro area), Oviedo (225,973), Badalona (220,977) and Terrassa (215 678) in Spain; and Braga (192,494), Amadora (175,558), Almada (174,030), Odivelas (144,549) and Coimbra (143,397) in Portugal.

Ecology

Forests

The woodlands of the Iberian Peninsula are distinct ecosystems. Although the various regions are each characterized by distinct vegetation, there are some similarities across the peninsula.

While the borders between these regions are not clearly defined, there is a mutual influence that makes it very hard to establish boundaries and some species find their optimal habitat in the intermediate areas.

East Atlantic flyway

The Iberian Peninsula in an important stopover on the East Atlantic flyway for birds migrating from northern Europe to Africa. For example, curlew sandpipers rest in the region of the Bay of Cádiz.[85]

In addition to the birds migrating through, some seven million wading birds from the north spend the winter in the estuaries and wetlands of the Iberian Peninsula, mainly at locations on the Atlantic coast. In Galicia are Ría de Arousa (a home of grey plover), Ria de Ortigueira, Ria de Corme and Ria de Laxe. In Portugal, the Aveiro Lagoon hosts Recurvirostra avosetta, the common ringed plover, grey plover and little stint. Ribatejo Province on the Tagus supports Recurvirostra arosetta, grey plover, dunlin, bar-tailed godwit and common redshank. In the Sado Estuary are dunlin, Eurasian curlew, grey plover and common redshank. The Algarve hosts red knot, common greenshank and turnstone. The Guadalquivir Marshes region of Andalusia and the Salinas de Cádiz are especially rich in wintering wading birds: Kentish plover, common ringed plover, sanderling, and black-tailed godwit in addition to the others. And finally, the Ebro delta is home to all the species mentioned above.[86]

Languages

With the sole exception of Basque, which is of unknown origin,[87] all modern Iberian languages descend from Vulgar Latin and belong to the Western Romance languages.[88] Throughout history (and pre-history), many different languages have been spoken in the Iberian Peninsula, contributing to the formation and differentiation of the contemporaneous languages of Iberia; however, most of them have become extinct or fallen into disuse. Basque is the only non-Indo-European surviving language in Iberia and Western Europe.[89]

In modern times, Spanish (cf. 30 to 40 million speakers), Portuguese (cf. around 10 million speakers), Catalan (cf. around 9 million speakers), Galician (cf. around 3 million speakers) and Basque (cf. around 1 million speakers)[90] are the most widely spoken languages in the Iberian Peninsula. Spanish and Portuguese have expanded beyond Iberia to the rest of world, becoming global languages.

Economy

Major industries include mining, tourism, small farms, and fishing. Because the coast is so long, fishing is popular, especially sardines, tuna and anchovies. Most of the mining occurs in the Pyrenees mountains. Commodities mined include: iron, gold, coal, lead, silver, zinc, and salt.

See also

|

|

Notes

^ In the local languages:- Spanish, Portuguese, Galician and Asturian: Península Ibérica (mostly rendered in lowercase in Spanish: península ibérica)

Spanish: [peˈninsula iˈβeɾika] (the same in Asturian)

Portuguese: [pɨˈnĩsulɐ iˈβɛɾikɐ]

Galician: [peˈninsula iˈβɛɾika]

Catalan: Península Ibèrica

Eastern Catalan: [pəˈninsulə iˈβɛɾikə]

Aragonese and Occitan: Peninsula Iberica

Aragonese: [peninˈsula iβeˈɾika]

Occitan: [peninˈsylɔ iβeˈɾikɔ; -beˈʀi-]

French: Péninsule Ibérique [penɛ̃syl ibeʁik]

Mirandese: Península Eibérica [p?ˈnĩsulɐ ejˈβɛɾikɐ]

Basque: Iberiar penintsula [iβeɾiar penints̺ula]

- Spanish, Portuguese, Galician and Asturian: Península Ibérica (mostly rendered in lowercase in Spanish: península ibérica)

^ In the local languages:- Spanish, Aragonese, Asturian and Galician: Iberia

Spanish: [iˈβeɾja] (the same in Aragonese and Asturian)

Galician: [iˈβɛɾja]

- Portuguese and Mirandese: Ibéria

Portuguese: [iˈβɛɾiɐ]

Mirandese: [iˈβɛɾiɐ]

- Catalan and Occitan: Ibèria

Eastern Catalan: [iˈβɛɾiə]

Occitan: [iˈβɛɾiɔ; -ˈbɛʀi-]

- French: Ibérie [ibeʁi]

- Basque: Iberia [iβeɾia]

- Spanish, Aragonese, Asturian and Galician: Iberia

References

^ "Iberian Peninsula". Retrieved 11 October 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Claire L. Lyons; John K. Papadopoulos (2002). The Archaeology of Colonialism. Getty Publications. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0-89236-635-4.

^ Strabo. "Book III Chapter 1 Section 6". Geographica.And also the other Iberians use an alphabet, though not letters of one and the same character, for their speech is not one and the same.

^ ab Charles Ebel (1976). Transalpine Gaul: The Emergence of a Roman Province. Brill Archive. pp. 48–49. ISBN 90-04-04384-5.

^ Ricardo Padrón (1 February 2004). The Spacious Word: Cartography, Literature, and Empire in Early Modern Spain. University of Chicago Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-226-64433-2.

^ Carl Waldman; Catherine Mason (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. p. 404. ISBN 978-1-4381-2918-1.

^ Strabo (1988). The Geography (in Ancient Greek and English). II. Horace Leonard Jones (trans.). Cambridge: Bill Thayer. p. 118, Note 1 on 3.4.19.

^ Herodotus (1827). The nine books of the History of Herodotus, tr. from the text of T. Gaisford, with notes and a summary by P.E. Laurent. p. 75.

^ ab III.4.19.

^ III.37.

^ III.17.

^ III.4.11.

^ Félix Gaffiot (1934). Dictionnaire illustré latin-français. Hachette. p. 764.

^ Greg Woolf (8 June 2012). Rome: An Empire's Story. Oxford University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-19-997217-3.

^ Berkshire Review. Williams College. 1965. p. 7.

^ Carlos B. Vega (2 October 2003). Conquistadoras: Mujeres Heroicas de la Conquista de America. McFarland. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7864-8208-5.

^ Virgil (1846). The Eclogues and Georgics of Virgil. Harper & Brothers. p. 377.

^ III.3.21.

^ White, Horace; Jona Lendering. "Appian's History of Rome: The Spanish Wars (§§6–10)". livius.org. pp. Chapter 7. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

^ "Polybius: The Histories: III.6.2". Bill Thayer.

^ ab Morris Student Plus, Basque-English dictionary

^ Jonathan Adams (26 February 2010). Species Richness: Patterns in the Diversity of Life. Springer. p. 208. ISBN 978-3-540-74278-4.

^ Persistent Entity. "Haplogroup R1b (Y-DNA)". NAP Professional. North American Pharmacal. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014.

^ Martí Oliver, Bernat (2012). "Redes y expansión del Neolítico en la Península Ibérica" (PDF). Rubricatum. Revista del Museu de Gavà (in Spanish). Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert (5): 549–553. ISSN 1135-3791. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

^ Case, H (2007). 'Beakers and Beaker Culture' Beyond Stonehenge: Essays on the Bronze Age in honour of Colin Burgess. Oxford: Oxbow. pp. 237–254.

^ Ontañón Peredo, Roberto (2003). Caminos hacia la complejidad: el Calcolítico en la región cantábrica. Universidad de Cantabria. p. 72. ISBN 9788481023466.

^ García Rivero, Daniel; Escacena Carrasco, José Luis (July–December 2015). "Del Calcolítico al Bronce antiguo en el Guadalquivir inferior. El cerro de San Juan (Coria del Río, Sevilla) y el 'Modelo de Reemplazo'" (PDF). Zephyrus (in Spanish). Universidad de Salamanca: 15–38. doi:10.14201/zephyrus2015761538. ISSN 0514-7336. Retrieved 1 September 2018.CS1 maint: Date format (link)

^ Vázquez Hoys, Dra. Ana Mª (15 May 2005). Santos, José Luis, ed. "Los Millares". Revista Terrae Antiqvae (in Spanish). UNED. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

^ Abraham Ibn Daud's Dorot 'Olam (Generations of the Ages): A Critical Edition and Translation of Zikhron Divrey Romi, Divrey Malkhey Yisra?el, and the Midrash on Zechariah. BRILL. 7 June 2013. p. 57. ISBN 978-90-04-24815-1. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

^ Julio Samsó (1998). The Formation of Al-Andalus: History and society. Ashgate. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-86078-708-2. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

^ Jaime Vicens Vives (1970). Approaches to the History of Spain. University of California Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-520-01422-0.

^ Darío Fernández-Morera (9 February 2016). The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise. Intercollegiate Studies Institute. p. 286. ISBN 978-1-5040-3469-2.

^ F. E. Peters (11 April 2009). The Monotheists: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in Conflict and Competition, Volume I: The Peoples of God. Princeton University Press. p. 182. ISBN 1-4008-2570-9.

^ Warfare in the Medieval World. Pen and Sword. 2006. ISBN 9781848846326.

^ A History of Europe: From 1378 to 1494.

^ The History of the Inquisition of Spain: From the Time of Its Establishment to the Reign of Ferdinand VII., Composed from the Original Documents of the Archives of the Supreme Council and from Those of Subordinate Tribunals of the Holy Office.

^ Jews of Spain: A History of the Sephardic Experience.

^ Teaching Jewish History.

^ Codex Judaica: Chronological Index of Jewish History, Covering 5,764 Years of Biblical, Talmudic & Post-Talmudic History.

^ Why Me God: A Jewish Guide for Coping and Suffering.

^ Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Volume I: Overviews and Topics; Volume II: Diaspora Communities.

^ The Christian Church from the 1st to the 20th Century.

^ The Routledge Atlas of Jewish History.

^ Anti-Jewish Riots in the Crown of Aragon and the Royal Response, 1391-1392. Cambridge University Press. 2016. p. 19. ISBN 9781107164512.

^ Religious Refugees in the Early Modern World: An Alternative History of the Reformation. Cambridge University Press. 2015. p. 108. ISBN 9781107024564.

^ The Kingfisher History Encyclopedia. p. 201. ISBN 9780753457849.

^ True Jew: Challenging the Stereotype.

^ The Expulsion of the Jews: Five Hundred Years of Exodus.

^ Dreams Deferred: A Concise Guide to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict and the Movement to Boycott Israel.

^ Secrecy and Deceit: The Religion of the Crypto-Jews.

^ The Jewish Time Line Encyclopedia: A Year-by-Year History From Creation to the Present. Jason Aronson, Incorporated. p. 178. ISBN 9781461631491.

^ Latin America in Colonial Times. Cambridge University Press. 2018. p. 27. ISBN 9781108416405.

^ A Concise Survey of Western Civilization: Supremacies and Diversities throughout History.

^ Spanish Royal Patronage 1412-1804: Portraits as Propaganda. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. 2018. p. 111. ISBN 9781527512290.

^ Notes On Entering Deen Completely: Islam as its followers know it.

^ We are All Moors: Ending Centuries of Crusades Against Muslims and Other Minorities.

^ Sánchez Blanco, Víctor (1988). "Las redes de Transporte entre la Península Ibérica y el resto de Europa". Cuadernos de Estrategia (in Spanish) (7): 21–32. ISSN 1697-6924 – via Dialnet.

^ III.1.3.

^ Fischer, T (1920). "The Iberian Peninsula: Spain". In Mill, Hugh Robert. The International Geography. New York and London: D. Appleton and Company. pp. 368–377.

^ These figures sum the figures given in the Wikipedia articles on the geography of Spain and Portugal. Most figures from Internet sources on Spain and Portugal include the coastlines of the islands owned by each country and thus are not a reliable guide to the coastline of the peninsula. Moreover, the length of a coastline may vary significantly depending on where and how it is measured.

^ Edmunds, WM; K Hinsby; C Marlin; MT Condesso de Melo; M Manyano; R Vaikmae; Y Travi (2001). "Evolution of groundwater systems at the European coastline". In Edmunds, W. M.; Milne, C. J. Palaeowaters in Coastal Europe: Evolution of Groundwater Since the Late Pleistocene. London: Geological Society. p. 305. ISBN 1-86239-086-X.

^ "Iberian Peninsula – Atlantic Coast". An Atlas of Oceanic Internal Solitary Waves (pdf). Global Ocean Associates. February 2004. Retrieved 9 December 2008.

^ "Los 10 ríos mas largos de España". 20 Minutos (in Spanish). 30 May 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

^ "2. El territorio y la hidrografía española: ríos, cuencas y vertientes". Junta de Andalucía. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

^ Manzano Cara, José Antonio. TEMA 8.- EL RELIEVE DE ESPAÑA (PDF). CEIP Madre de la Luz (in Spanish). Junta de Andalucía. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

^ Manuel, Piçarra, José; C., Gutiérrez-Marco, J.; A., Sá, Artur; Carlos, Meireles,; E., González-Clavijo, (1 June 2006). "Silurian graptolite biostratigraphy of the Galicia - Tras-os-Montes Zone (Spain and Portugal)".

^ Edited by W Gibbons & T Moreno, Geology of Spain, 2002,

ISBN 978-1-86239-110-9

^ Jones, Peter. "Introduction to the Birds of Spain". www.spanishnature.com.

^ "Standard climate values for Almería". Aemet.es. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

^ "Standard climate values for Córdoba". Aemet.es. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

^ "Standard climate values for A Coruña". Aemet.es. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

^ "Standard Climate Values, Spain". Aemet.es. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

^ "IPMA Climate Normals". ipma.pt. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

^ Population only includes the inhabitants of mainland Spain (excluding the Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Ceuta and Melilla), mainland Portugal (excluding Madeira and Azores), Andorra and Gibraltar.

^ Census data , "Official Spanish census"

^ Census data , "Portuguese census department"

^ Peter Sahlins (1989). Boundaries: The Making of France and Spain in the Pyrenees. University of California Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-520-91121-5.

^ Paul Wilstach (1931). Along the Pyrenees. Robert M. McBride Company. p. 102.

^ James Erskine Murray (1837). A Summer in the Pyrenees. J. Macrone. p. 92.

^ "Espagne • Fiche pays • PopulationData.net".

^ http://www.demographia.com/db-worldua.pdf

^ http://www.demographia.com/db-worldua.pdf Demographia: World Urban Areas

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2013.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "Urban Audit - CityProfiles". Archived from the original on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 9 April 2009.

^ Hortas, Francisco; Jordi Figuerols (2006). "Migration pattern of Curlew Sandpipers Calidris ferruginea on the south-western coastline of the Iberian Peninsula" (pdf). International Wader Studies. 19: 144–147. Retrieved 7 December 2008.

^ Dominguez, Jesus (1990). "Distribution of estuarine waders wintering in the Iberian Peninsula in 1978–1982" (PDF). Wader Study Group Bulletin. 59: 25–28.

^ "El misterioso origen del euskera, el idioma más antiguo de Europa". Semana (in Spanish). 18 September 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

^ Fernández Jaén, Jorge. "El latín en Hispania: la romanización de la Península Ibérica. El latín vulgar. Particularidades del latín hispánico". Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 September 2018.

^ Echenique Elizondo, M.ª Teresa (March 2016). "Lengua española y lengua vasca: Una trayectoria histórica sin fronteras" (PDF). Revista de Filología (in Spanish). Instituto Cervantes (34): 235–252. ISSN 0212-4130. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

^ "El Gobierno Vasco ha presentado los resultados más destacados de la V. Encuesta Sociolingüística de la CAV, Navarra e Iparralde". Eusko Jaurlaritza (in Basque). 18 July 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iberian Peninsula. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Iberian Peninsula. |

Arioso, Pāolā; Diego Meozzi. "Iberian Peninsula•Links". Stone Pages. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

Flores, Carlos; Nicole Maca-Meyer; Ana M Gonzalez; Peter J Oefner; Peidong Shen; Jose A Perez; Antonio Rojas; Jose M Larruga; Peter A Underhill (2004). "Reduced genetic structure of the Iberian Peninsula revealed by Y-chromosome analysis: implications for population demography" (PDF). European Journal of Human Genetics. 12 (10): 855–863. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201225. PMID 15280900. Archived from the original (pdf) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

Loyd, Nick (2007). "IberiaNature: A guide to the environment, climate, wildlife, geography and nature of Spain". Retrieved 4 December 2008.

Silva, Luís Fraga de. "Ethnologic Map of Pre-Roman Iberia (circa 200 B.C.). NEW VERSION #10" (in English, Portuguese, and Latin). Associação Campo Arqueológico de Tavira, Tavira, Portugal. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 4 December 2008.