Codex Borgia

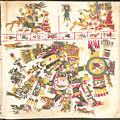

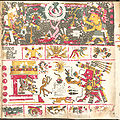

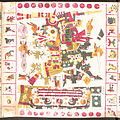

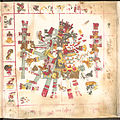

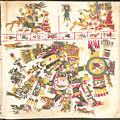

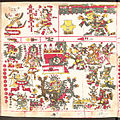

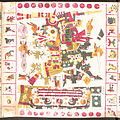

Page 71 of the Codex Borgia, depicting the sun god, Tonatiuh.

The Codex Borgia or Codex Yoalli Ehēcatl is a Mesoamerican ritual and divinatory manuscript. It is one of a handful of codices that some scholars believe to have been written before the Spanish conquest of Mexico, somewhere within what is now southern or western Puebla, though some scholars also argue that was produced in the first decades after the conquest as a copy of an earlier precolumbian codex. The Codex Borgia is a member of, and gives its name to, the Borgia Group of manuscripts.

The codex is made of animal skins folded into 39 sheets. Each sheet is a square 27 cm by 27 cm (11x11 inches), for a total length of nearly 11 meters (35 feet). All but the end sheets are painted on both sides, providing 76 pages. The codex is read from right to left. Pages 29–46 are oriented perpendicular to the rest of the codex. The top of this section is the right side of page 29, and the scenes are read from top to bottom. So the reader must rotate the manuscript 90 degrees in order to view this section correctly. The Codex Borgia is organized into a screen-fold. Single sheets of the hide are attached as a long strip and then folded back and forth. Images were painted on both sides and painted over with a white gesso. Stiffened leather are used as end pieces by gluing the first and last strips in order to create a cover. The edges of the pages are overlapped and glued together, making the sheet edges hardly visible under the white gesso finish. The gesso creates a stiff, smooth, white finished surface that preserves the images below.

The Codex Borgia features eighteen pages of an astronomical narrative that shows the yearlong alteration of the rainy and dry season.

The Codex Borgia is named after the Italian Cardinal Stefano Borgia, who owned it before it was acquired by the Vatican Library.

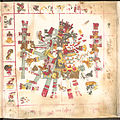

Codex Borgia. Modern reproduction.

Contents

1 History

2 Contents

2.1 1–8

2.2 9–14

2.3 15–17

2.4 18–21

2.5 22–28

2.6 29–46

2.7 47–56

2.8 57–60

2.9 61–70

2.10 71–76

3 References

4 External links

History

The Codex Borgia was brought to Europe, likely Italy, some time in the early Spanish Colonial period. It was discovered in 1805 by Alexander von Humboldt among the effects of Cardinal Stefano Borgia. The Codex Borgia is presently housed in the Apostolic Library, the Vatican, and has been digitally scanned and made available to the public.

Contents

1–8

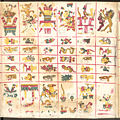

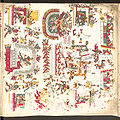

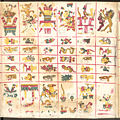

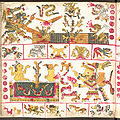

The first eight pages list the 260 day signs of the tonalpohualli (day sign), each trecena of 13 signs forming a horizontal row spanning two pages. Certain days are marked with a footprint symbol. Divinatory symbols are placed above and below the day signs.

Sections parallel to this are contained in the first eight pages of the Codex Cospi and the Codex Vaticanus B. However, while the Codex Borgia is read from right to left, these codices are read from left to right. Additionally, the Codex Cospi includes the Lords of the Night alongside the day signs.

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

9–14

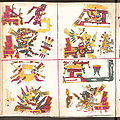

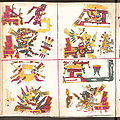

Pages 9 to 13 are divided into four quarters. Each quarter contains one of the twenty day signs, its patron deity, and associated symbols.

Page 14 is divided into nine sections for each of the nine Lords of the Night. They are accompanied by a day sign and symbols indicating positive or negative associations.

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

15–17

Pages 15 to 17 depict deities associated with childbirth. Each of the twenty sections contains four day signs.

The bottom section of page 17 contains a large depiction of Tezcatlipoca, with day signs associated with different parts of his body.

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

18–21

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

22–28

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

29–46

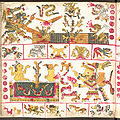

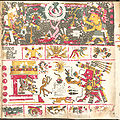

Pages 29 through 46 of the codex constitute the longest section of the codex, and the most enigmatic. The pages refer to different veintena festivals. Together these images represent a 20-day period for the veintena cycle. The glyphs refer to dry and rainy seasons. They apparently show a journey but the complex iconography and the lack of any comparable document have led to a variety of interpretations ranging from an account of actual astronomical and historical events, to the passage of Quetzalcoatl—as a personification of Venus[citation needed]—through the underworld, to a "cosmic narrative of creation". Pages 37 and 38 depict Xolotl holding a Xiuhcoatl or "fire serpent" descending into the underworld with lightning. The sequence apparently ends with a New Fire ceremony, marking the end of one 52-year cycle, and the start of another.

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

47–56

Pages 47 through 56 show a variety of deities, sacrifices, and other complex iconography.

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

57–60

Pages 57 through 60 allowed the priest to determine the prospects for favorable and unfavorable marriages according to the numbers within the couple’s names.

Page 57

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

61–70

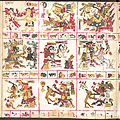

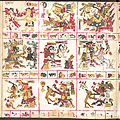

Pages 61 through 70 are similar to the first section, showing various day signs winding around scenes of deities. Each of the 10 pages shows 26 day signs.

Page 61

Page 62

Page 63

Page 64

Page 65

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

71–76

Page 71 depicts Tonatiuh, the sun god, receiving blood from a decapitated bird. Surrounding the scene are the thirteen Birds of the Day, corresponding to each of the thirteen days of a trecena. Page 72 depicts four deities with day signs connected to parts of their bodies. Each deity is surrounded by a serpent. Page 73 depicts the gods Mictlantecuhtli and Quetzalcoatl seated back to back, similar to page 56. They likewise have day signs attached to various parts of their bodies, and the entire scene is encircled by day signs.

Page 71

Page 72

Page 73

Page 74

Page 75

Page 76

References

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

Milbrath, Susan (2013). Heaven and Earth in Ancient Mexico: Astronomy and Seasonal Cycles in the Codex Borgia. The Linda Schele Series in Maya and Pre-Columbian Studies. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-74373-1. OCLC 783173291..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

Boone, Elizabeth Hill (2007). Cycles of Time and Meaning in the Mexican Books of Fate. Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long series in Latin American and Latino art and culture. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71263-8. OCLC 71632174.

Brotherston, Gordon (1999). "The yearly seasons and skies in the Borgia and related codices". Arara: Art and Architecture of the Americas. Colchester, UK: University of Essex. 2. ISSN 1465-5047. OCLC 163473451. Archived from the original (eJournal online text) on 2008-02-21.

Díaz, Gisele; Alan Rodgers; Bruce E. Byland (1993). The Codex Borgia: A Full-Color Restoration of the Ancient Mexican Manuscript. New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-27569-8. OCLC 27641334.

Jansen, Maarten (2001). "Borgia, Codex". In David Carrasco. The Oxford encyclopedia of Mesoamerican cultures: The civilizations of Mexico and Central America. Vol. 1. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 94–98. ISBN 0-19-514255-1. OCLC 44019111.

Jansen, Maarten; Gabina Aurora Pérez Jiménez (2004). "Renaming the Mexican Codices". Ancient Mesoamerica. London and New York: Cambridge University Press. 15 (2): 267–271. doi:10.1017/S0956536104040179. ISSN 0956-5361. OCLC 89722889.

Nowotny, Karl Anton (2005). Tlacuilolli: style and contents of the Mexican pictorial manuscripts with a catalog of the Borgia Group. George A. Everett, Jr. and Edward B. Sisson (trans. and eds.), with a foreword by Ferdinand Anders. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3653-7. OCLC 56527102.

External links

- A list of the "proper sequence" of sections of codices in the Borgia group.

- Facsimile of Codex Borgianus Mexicanus 1

- Digital scans of the Codex Borgianus as produced by the Vatican